[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, June 25th, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | Cartoonist Lynda Barry Teaches You How to Draw

Friend, are you paralyzed by your ironclad conviction that you can't draw? Professor Chewbacca aka Professor Old Skull aka cartoonist Lynda Barry has had quite enough of that nonsense! So stop dissembling, grab a pen and a hand-sized piece of paper, and follow her instructions to Anne Strainchamps, host of NPR's To The Best Of Our Knowledge, below. It’s better to throw yourself into it without knowing precisely what the ten minute exercise holds (other than drawing, of course). We know, we know, you can’t, except that you can. Like Strainchamps, you’re probably just rusty. Don’t judge yourself too harshly if things look “terrible.” In Barry’s view, that’s relative, particularly if you were drawing with your eyes closed. A neurology nerd, Barry cites Girija Kaimal, Kendra Ray, and Juan Muniz’ study Reduction of Cortisol Levels and Participants' Responses Following Art Making. It’s the action, not the subjective artistic merit of what winds up on the page that counts in this regard. For more of Barry’s exercises and delightfully droll presence, check out this playlist on Dr. Michael Green's Graphic Medicine Channel. Related Content: Follow Cartoonist Lynda Barry’s 2017 “Making Comics” Class Online, Presented at UW-Wisconsin Join Cartoonist Lynda Barry for a University-Level Course on Doodling and Neuroscience Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine... Follow her @AyunHalliday. Cartoonist Lynda Barry Teaches You How to Draw is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | The Meandering Mississippi River and How It Evolved Over Thousands of Years Visualized in Brilliant Maps from 1944

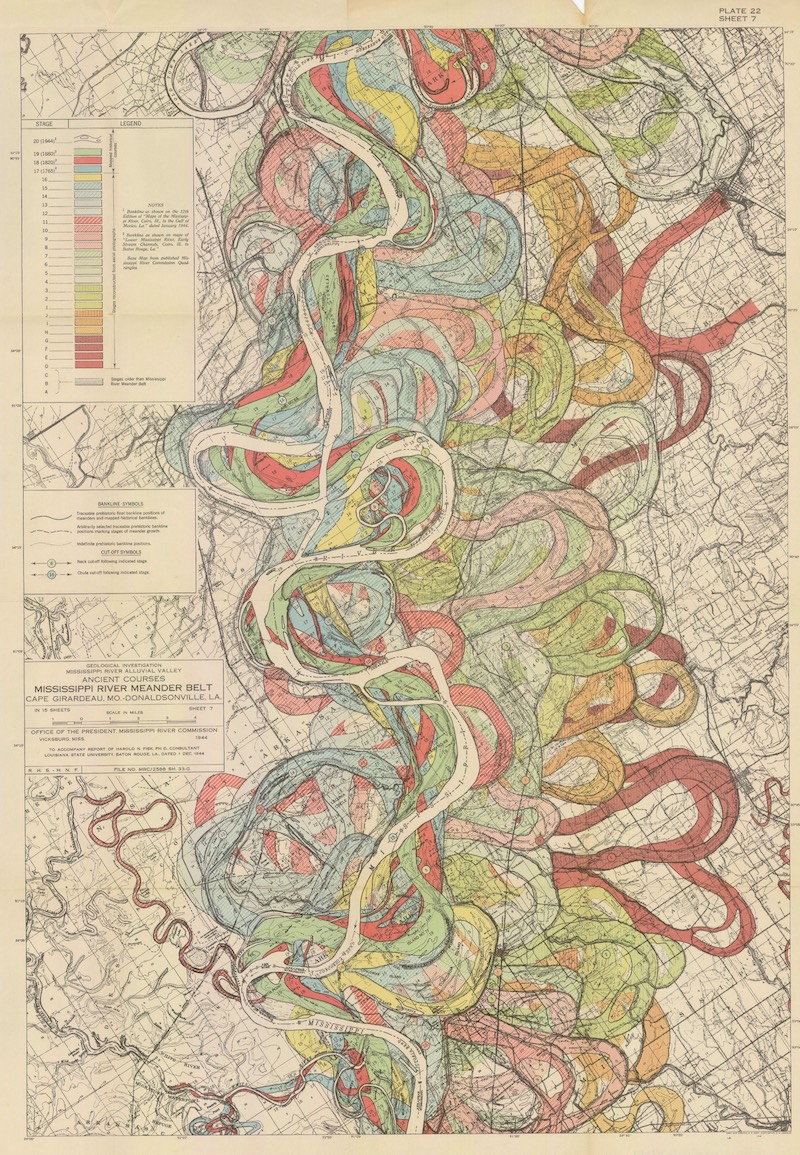

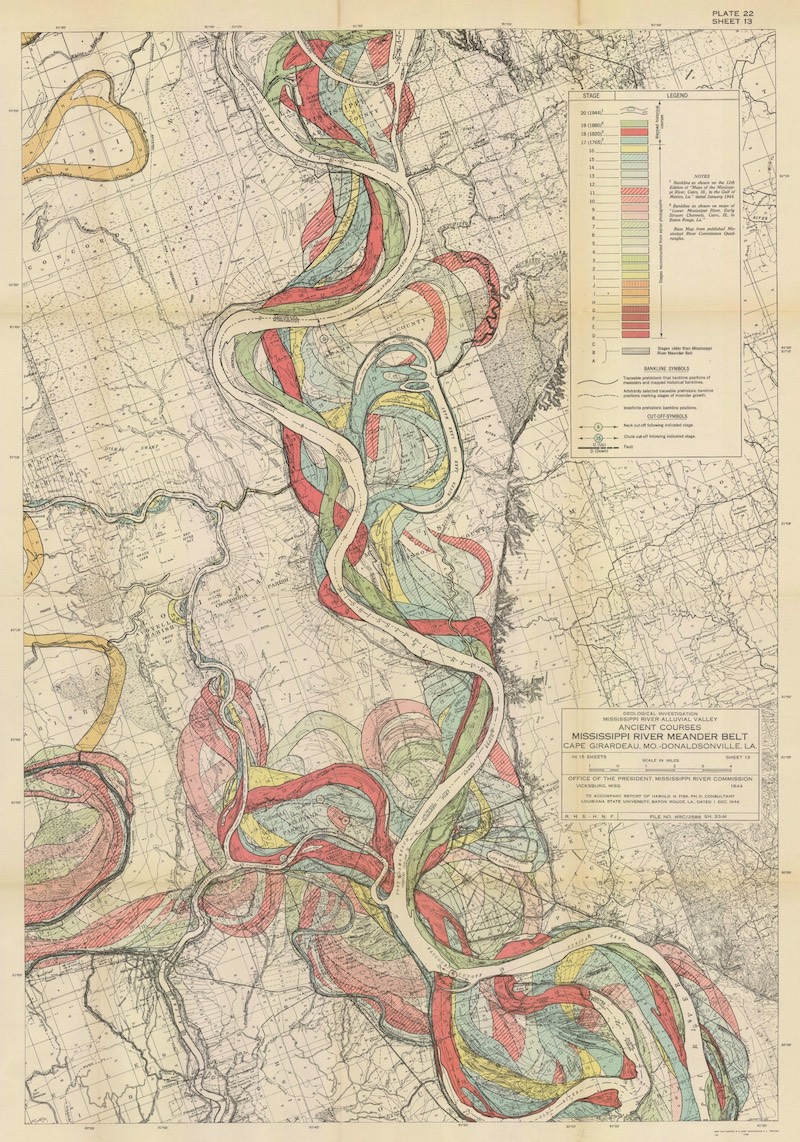

Given that Turkey's Büyük Menderes River was historically known as the Meander, you might well imagine how un-straightforward a path it takes through the country. But the English adjective descended from its name describes a fair few other twisting, turning rivers as well, and also a form of river mapping that suits them. "I have long admired the Mississippi River meander maps designed by Army Corps of Engineers cartographer Harold Fisk," writes Jason Kottke at Kottke.org by way of an introduction to his short essay on them at the site of printmaker 20x200. "In their relentless flow to lower ground, rivers like to roam over the landscape, cutting through solid rock and loamy soil alike, gaining advantage here and there where they can," goes Kottke's explanation of how meandering rivers come to be. "The best and easiest course for a river to take downhill is its current course... right up until the moment when it's not." Each color in Fisk's meander maps of the longest river in North America "represents a new course, a marker of each time a bend had become too bendy and the river 'decided' to take a more direct path." Kottke summarizes these maps' appeal succinctly: "They are time machines."

"Standing before a painting by Hilma af Klint, a sculpture by Bernini, or a cave painting in Chauvet, France draws you back in time in a powerful way: you know you're standing precisely where those artists stood hundreds or even thousands of years ago, laying paint to surface or chisel to stone." Here, thanks to a "clever mapmaker with an artistic eye," we can imagine the Mississippi "as it was during the European exploration of the Americas in the 1500s, during the Cahokia civilization in the 1200s (when this city's population matched London's), when the first humans came upon the river more than 12,000 years ago, and even back to before humans, when mammoths, camels, dire wolves, and giant beavers roamed the land and gazed upon the river." You can buy prints of three different Mississippi meander maps from 20x200, all of them originally part of Fisk's report "Geological Investigation of the Alluvial Valley of the Lower Mississippi River completed in 1944. The study was made to learn about the formation of the valley over time, and about the major factors that dictate its flow and flooding in the modern era." Fisk drew upon data collected through approximately 16,000 borings, and "also found the river's heart in this jumble of loops and purls," producing a reflection of the river's distinctive personality in "this explosive, autumn-colored palette." Regarding these maps, we can't help but wonder in what shape some future team of intrepid surveyors will find the Mississippi a few thousand years hence — and what new words, in what languages, that shape might inspire. via Kottke Related Content: All the Rivers & Streams in the U.S. Shown in Rainbow Colours: A Data Visualization to Behold William Faulkner Draws Maps of Yoknapatawpha County, the Fictional Home of His Great Novels Learn the Untold History of the Chinese Community in the Mississippi Delta View and Download Nearly 60,000 Maps from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Download 67,000 Historic Maps (in High Resolution) from the Wonderful David Rumsey Map Collection Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. The Meandering Mississippi River and How It Evolved Over Thousands of Years Visualized in Brilliant Maps from 1944 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | Two Animated Maps Show the Expansion of the U.S. from the Different Perspectives of Settlers & Native Peoples

After John Ford, the history of U.S. expansion went by the name “How the West Was Won.” Decades earlier, in his essay “Annexation,” Jacksonian journalist John O’Sullivan famously coined the phrase “manifest destiny.” Historian Richard Slotkin called it “regeneration through violence” and novelist Cormac McCarthy summed up the jagged, ever-moving line of westward expansion from sea to sea with two words: Blood Meridian. Indigenous versions of the story do not tend to enter common parlance in quite the same way, a fact upon which Vine Deloria, Jr. remarks in his “Indian Manifesto,” Custer Died for Your Sins. Violence is always central to the story. Usually the savagery of Native people is taken for granted. Savagery of settlers may be more or less emphasized. Yet the long history of land theft over the course of the centuries is also one of broken treaty after treaty.

Caught between warring European empires, Indigenous nations made the best deals they could with the advancing U.S. and its army of Civil War veterans. “From this humble beginning the federal government stole some two billion acres of land and continues to take what it can without arousing the ire of the ignorant public.” The brutality of the 19th century became professionalized, carried out by regulars in uniform, hence the detached language of “Indian wars.” These were followed by other kinds of violence: institutionalized paternalism, further encroachment and enclosure, and the forced removal of thousands of children from their parents and into reeducation camps. The two maps you see here, with sweepingly broad visual gestures in gif form, illustrate the 19th century seizure of land across the North American continent from the perspective of a U.S. national history and that of an Indigenous multi-national history. The map at the top traces the story from the country's beginnings in the 13 colonies to the annexation, purchase, and finally statehood of Hawaii and Alaska in 1959.

The above map is more focused, spanning the years 1810 to 1891. As Nick Routley points out in a post at Visual Capitalist, “five of the largest expansion events in U.S. history” took place during the 1800s, though the first one he cites falls outside the timeline above. The 1803 Louisiana Purchase ended up acquiring what now makes up “nearly 25% of the current territory of the United States, stretching from New Orleans all the way up to Montana and North Dakota.” Other notable events include the 1819 purchase of Florida from Spain by John Quincy Adams, the aforementioned purchase of Alaska from Russia, and the 1845 annexation of Texas. The Mexican-American War of 1848 gets less mention these days, though it expanded slavery and was quite hotly debated at the time by such principled figures as Henry David Thoreau, who refused to pay his poll tax over it and wrote “Civil Disobedience” while in jail. In the so-called Mexican Cession, Texas became a state and “the United States took control of a huge parcel of land that includes the present-day states of California, Nevada, and Utah, as well as portions of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming.” Mexico, on the other hand, “saw the size of their territory halved.” After each seizure of territory, mass migrations westward commenced in wave upon wave. Routely does not survey these migration events, but you can learn about them in accounts like Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s Indigenous People’s History of the United States and Deloria’s manifesto. When we approach the founding and expansion of the U.S. from multiple perspectives, both visual and historical, we understand why critical historians often use the phrase “settler colonialism” rather than “westward expansion” or its synonyms. And why the overused and limited phrase “nation of immigrants” might just as well be “nation of migrants.” Related Content: Native Lands: An Interactive Map Reveals the Indigenous Lands on Which Modern Nations Were Built The Atlantic Slave Trade Visualized in Two Minutes: 10 Million Lives, 20,000 Voyages, Over 315 Years Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Two Animated Maps Show the Expansion of the U.S. from the Different Perspectives of Settlers & Native Peoples is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 7:02p | In 1886, the US Government Commissioned 7,500 Watercolor Paintings of Every Known Fruit in the World: Download Them in High Resolution

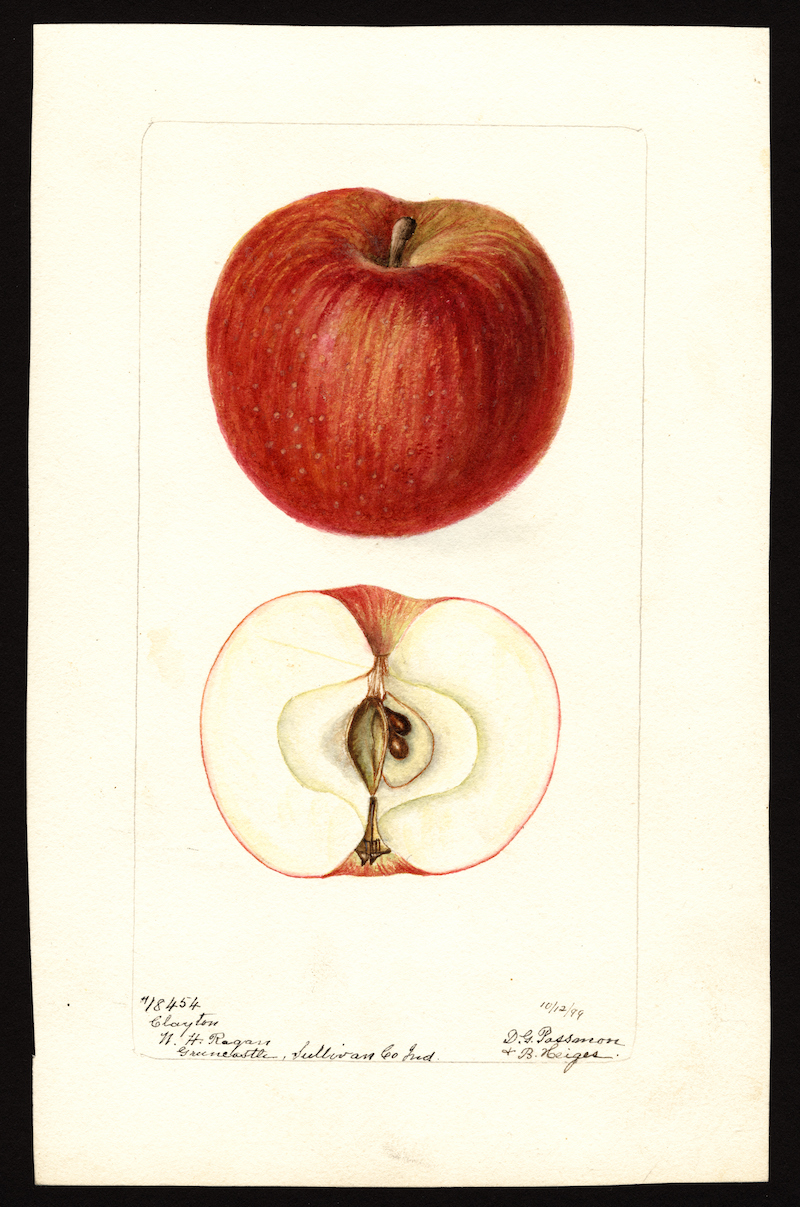

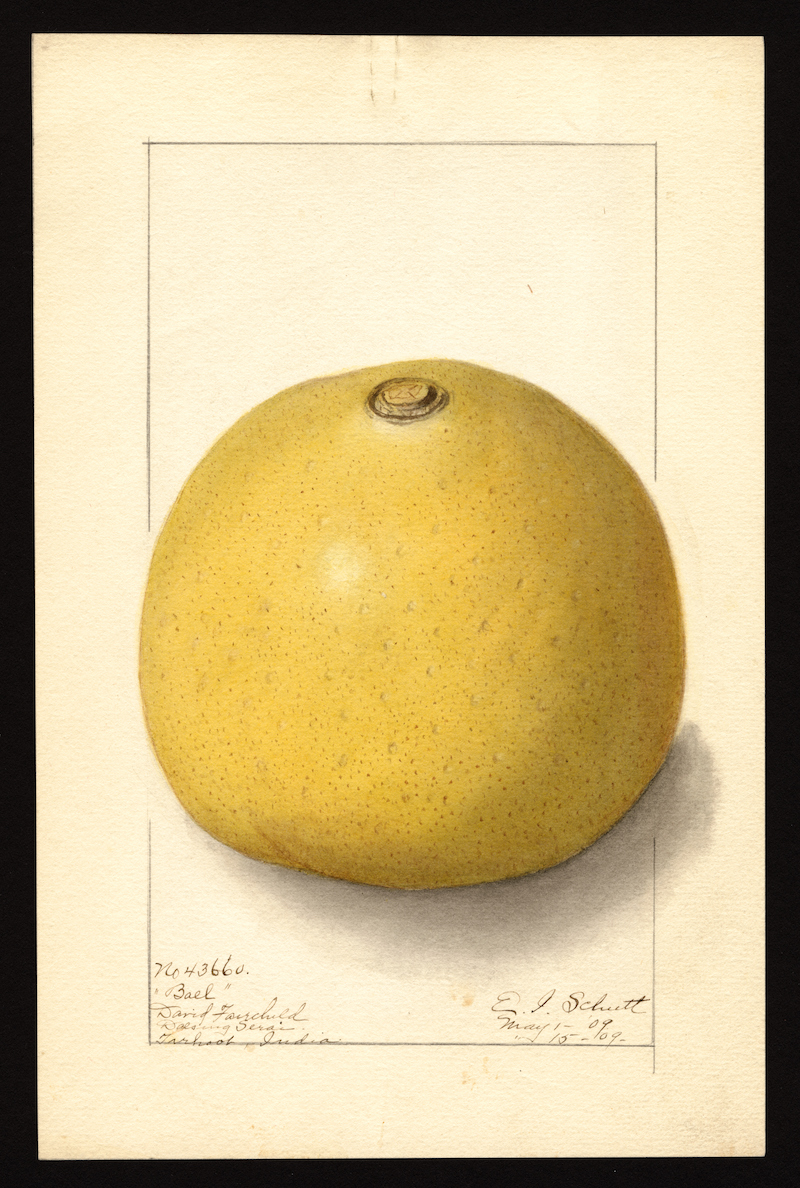

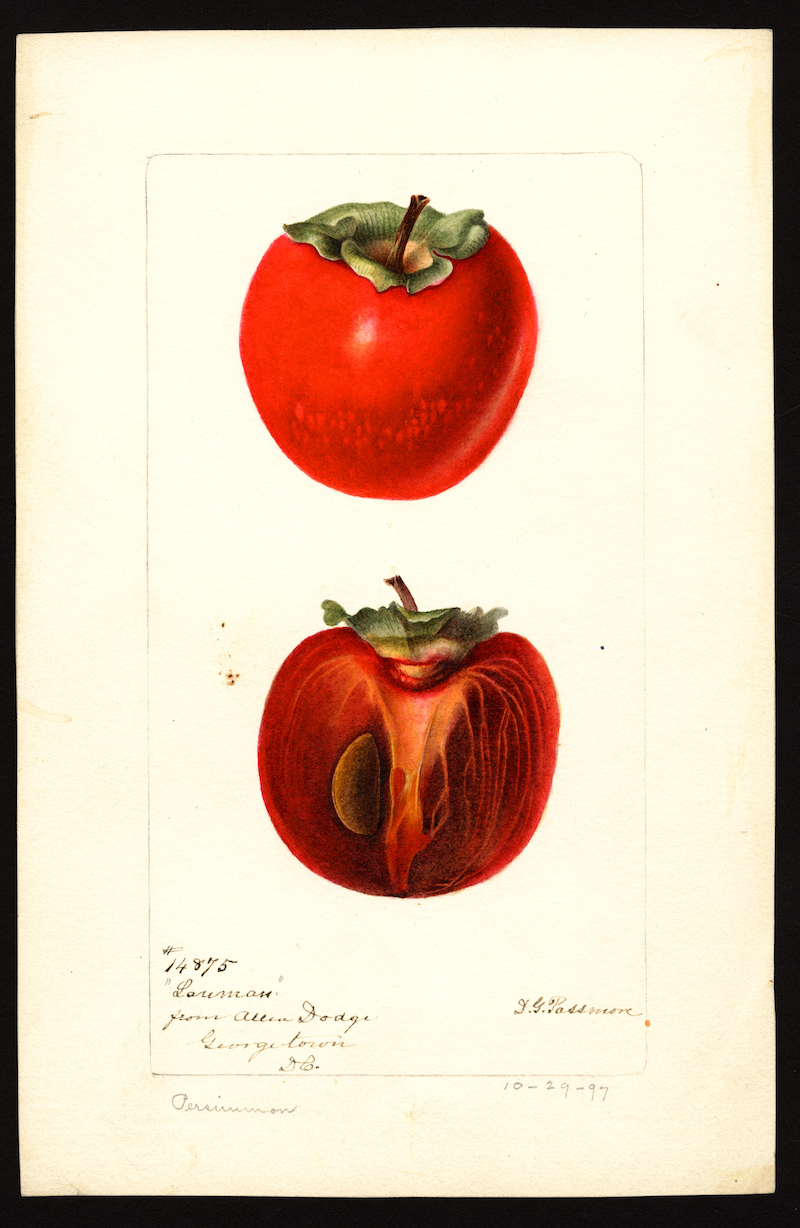

T.S. Eliot asks in the opening stanzas of his Choruses from the Rock, “where is the knowledge we have lost in information?” The passage has been called a pointed question for our time, in which we seem to have lost the ability to learn, to make meaningful connections and contextualize events. They fly by us at superhuman speeds; credible sources are buried between spurious links. Truth and falsehood blur beyond distinction. But there is another feature of the 21st century too-often unremarked upon, one only made possible by the rapid spread of information technology. Vast digital archives of primary sources open up to ordinary users, archives once only available to historians, promising the possibility, at least, of a far more egalitarian spread of both information and knowledge. Those archives include the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection, “over 7,500 paintings, drawings, and wax models commissioned by the USDA between 1886 and 1942,” notes Chloe Olewitz at Morsel. The word “pomology,” “the science and practice of growing fruit,” first appeared in 1818, and the degree to which people depended on fruit trees and fruit stores made it a distinctively popular science, as was so much agriculture at the time.

But pomology was growing from a domestic science into an industrial one, adopted by “farmers across the United States,” writes Olewitz, who “worked with the USDA to set up orchards to serve emerging markets” as “the country’s most prolific fruit-producing regions began to take shape.” Central to the government agency’s growing pomological agenda was the recording of all the various types of fruit being cultivated, hybridized, inspected, and sold from both inside the U.S. and all over the world. Prior to and even long after photography could do the job, that meant employing the talents of around 65 American artists to “document the thousands and thousands of varieties of heirloom and experimental fruit cultivars sprouting up nationwide.” The USDA made the full collection public after Electronic Frontier Foundation activist Parker Higgins submitted a Freedom of Information Act request in 2015.

Higgins saw the project as an example of “the way free speech issues intersect with questions of copyright and public domain,” as he put it. Historical government-issued fruit watercolors might not seem like the obvious place to start, but they’re as good a place as any. He stumbled on the collection while either randomly collecting information or acquiring knowledge, depending on how you look at it, “challenging himself to discover one new cool public domain thing every day for a month.”

It turned out that access to the USDA images was limited, “with high resolution versions hidden behind a largely untouched paywall.” After investing $300,000, they had made $600 in fees in five years, a losing proposition that would better serve the public, the scholarly community, and those working in-between if it became freely available. You can explore the entirety of this tantalizing collection of fruit watercolors, ranging in quality from the workmanlike to the near sublime, and from unsung artists like James Marion Shull, who sketched the Cuban pineapple above, Ellen Isham Schutt, who brings us the Aegle marmelos, commonly called “bael” in India, further up, and Deborah Griscom Passmore, whose 1899 Malus domesticus, at the top, describes a U.S. pomological archetype.

It’s easy to see how Higgins could become engrossed in this collection. Its utilitarian purpose belies its simple beauty, and with 3,800 images of apples alone, one could get lost taking in the visual nuances—according to some very prolific naturalist artists—of just one fruit alone. Higgins, of course, created a Twitter bot to send out random images from the archive, an interesting distraction and also, for people inclined to seek it out, a lure to the full USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection. At what point does an exploration of these images tip from information into knowledge? It's hard to say, but it’s unlikely we would pursue either one if that pursuit didn’t also include its share of pleasure. Enter the USDA's Pomological Watercolor Collection here to new and download over 7,500 high-resolution digital images like those above. via Morsel. Related Content: Two Million Wondrous Nature Illustrations Put Online by The Biodiversity Heritage Library Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness In 1886, the US Government Commissioned 7,500 Watercolor Paintings of Every Known Fruit in the World: Download Them in High Resolution is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/06/25 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |