[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, July 10th, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | Lennon or McCartney? Scientists Use Artificial Intelligence to Figure Out Who Wrote Iconic Beatles Songs

Do you agonize over the fact that you don’t know for certain who wrote what percentage of your favorite Beatles songs? Do you need to know if a line or phrase is Lennon or McCartney’s before you can enjoy “A Hard Day’s Night,” “In My Life,” and other timeless tunes? Have you lost sleep over the disputed authorship of “Do You Want to Know a Secret”? I hope not. As Lennon/McCartney themselves wrote, in the end, the songs we love are equal to the love we give the songs…. or something like that. How much we can say with certainty who penned which lyric or melody or played which riff or rhythm part doesn’t add to our emotional experience. But that knowledge does add more to our appreciation than fodder for forum wars or lawsuits. Pulling these iconic songs into their constituent parts helps confirm our understanding of how those parts contributed differently to making the whole evolve; how Lennon’s directness and simplicity complemented and contrasted with McCartney’s use of “more non-standard musical motifs” and a higher degree of complexity. Or, at least, that’s what an AI found when it analyzed hundreds of Beatles hits in an effort to “build a ‘musical fingerprint’ for each songwriter,” reports Alex Matthews-King at the Independent. After putting the machine learning algorithm through an initial training phase of “listening” to a complete works, researchers at Harvard “asked” the program to assess “iconic songs, or musical fragments, recorded between 1962 and 1966, where debate rages over who was the major influence.” Much of that debate has been fueled by the songwriters themselves, whose memories in interviews conflict, but who are generally thought to have written most songs individually under their joint songwriting partnership. The scientists from Harvard and Dalhousie University in Canada were able to gauge with somewhere around 76 percent accuracy whether songs or parts of songs were written by Lennon or McCartney. (Spoiler alert: The AI "was able to identify some, including 'Ask Me Why', 'Do You Want to Know a Secret' and the bridge to 'A Hard Day's Night', as belonging to John Lennon with up to 90 per cent certainty," writes The Daily Mail.) Senior lecturer in statistics at Harvard and paper author Mark Glickman explains the larger purpose of the project to the Financial Times: “Our work is essentially a blueprint for those wanting to follow changes in music over time. Using our machine learning model, you could potentially home in on all the different influences of a given musician.” If you’re using their work to win arguments, be prepared to explain how the study obtained its results and why they are any more reliable than decades of detective work and expert listening by humans. As a non-statistics person, I’ll leave that explanation to more qualified individuals. I’m satisfied: whether McCartney wrote all of the music for “In My Life” or just the bridge, as Lennon claimed, won’t change the way it moves me one bit. Related Content: A Brief History of Sampling: From the Beatles to the Beastie Boys Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Lennon or McCartney? Scientists Use Artificial Intelligence to Figure Out Who Wrote Iconic Beatles Songs is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” and the Apollo 11 Moon Landing Turn 50 This Month: Celebrate Two Giant Leaps That Took Place 9 Days Apart One might call the explosion of “space rock” in the late 60s another kind of escapism, a turn from the heaviness on planet Earth when the Age of Aquarius started to get seriously dark. Assassinations, riots, illegal wars, blunt state repression, counterculture fragmentation, violence everywhere, it seemed. Hallucinogens played their part in guiding the music’s direction, but who could blame bands and fans of bands like the Grateful Dead, Pink Floyd, Hawkwind, or Hendrix for turning their gaze skywards and contemplating the stars? One might also make the case that so-called “space rock”—psych-rock that directly or indirectly referenced outer space, space travel, and sci-fi themes, while sounding itself like the music of the spheres on acid—in fact, turned squarely toward the most technologically-advanced, ambitious proxy battle of the entire Cold War. The very earthly space race made a fitting subject for rock opera—a perfect stage set for imaginative songs about alienation, isolation, and technological inhumanity. All of these themes come together in a celestial harmony in David Bowie’s 1969 single, “Space Oddity,” released on July 11th 1969 and inspired by Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, both cultural artifacts that anticipated the drama of the Apollo 11 moon landing. The excitement Kubrick’s film and Bowie’s song helped generate is odd, however, considering that both narratives end with their protagonists lost in outer space forever. This didn’t stop the BBC from using “Space Oddity” to soundtrack their Apollo coverage, “despite its chilling conclusion,” writes Jason Heller, author of Strange Stars: David Bowie, Pop Music, and the Decade Sci-Fi Exploded. The song’s scenario “couldn’t have been further from the typical cheerleading of the astronauts that was being conducted by the media. No one was more surprised than Bowie,” who commented:

“Of course,” says Bowie, ”I was overjoyed that they did” run with the song. It had been his label’s intent to garner this kind of exposure when they rushed the record’s release to “capitalize on the Apollo craze.” "Space Oddity" made it to number five on the UK charts. But if Bowie was making any comment on the moon mission, at first it seems he did so only indirectly, inspired more by cinema than current events. He found 2001 “amazing,” he commented, adding, “I was out of my gourd anyway, I was very stoned when I went to see it, several times, and it was really a revelation to me.” The song, he says, came out of that enhanced viewing experience. Heller writes of several more of Bowie’s literary sci-fi influences, but not of a particular interest in the Apollo program. Yet Bowie, who recorded the first “Space Oddity” demo in January of 1969, did say he wanted the song “to be the first anthem of the Moon.” The lyrics also “came from a feeling of sadness,” he said, about the space program's direction. “It has been dehumanized,” he said. “Space Oddity” represented a deliberate “antidote to space fever,” which is maybe why the song didn't catch on in the U.S. until the ‘70s. This was not a song about planting a flag of conquest. Journalist Chris O’Leary remembers Bowie making even more pointed commentary, considering “the fate of Major Tom to be the technocratic American mind coming face-to-face with the unknown and blanking out.” The song heralded not only a pivotal scientific achievement but a cultural break: “It was probably not hyperbole to assert that the Age of Aquarius ended when man walked on the Moon,” writes sociologist Philip Ennis. Or as Camille Paglia interpreted events in Bowie’s song, “we sense that the ‘60s counterculture has transmuted into a hopelessness about political reform.” This may seem like a lot of interpretation to lay on what Bowie himself called a “song-farce,” but when we’re talking about Bowie’s songwriting, even throwaway lines seem filled with portent. And when it comes to that supremely ambivalent couplet “Planet Earth is blue / And there’s nothing I can do,” we find ourselves legitimately asking along with Heller, is this “anthem or requiem? Celebration or deconstruction?” It has been all these things—the “defining song of the Space Age,” sung by astronauts themselves while floating in the tin can of the International Space Station, and soon to be broadcast at the Kennedy Center in a new video celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing. The video at the NASA event on July 20th will commemorate the event with “footage of David Bowie performing Space Oddity at his 50th birthday concert at Madison Square Garden in 1997.” At the top of the post, see a later video for the song (the first film Bowie made, in 1969, would not emerge until 1984); further up, see an excellent live performance as Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars; and just above, see a young, fresh, bell-bottomed, pre-glam Bowie play “Space Oddity” live on TV in 1969. As we remember the 50th anniversary of the moon landing this month, we also celebrate the release of “Space Oddity” just nine days earlier, the song that first launched Bowie’s career as a spacefaring rock star. He couldn’t have predicted the success of the Apollo 11 mission, but now it seems we cannot properly remember it without also reflecting on his prescient pop critique—an attempt, he said, “to relate science and emotion.” Related Content: Astronaut Chris Hadfield Sings David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” On Board the International Space Station How “Space Oddity” Launched David Bowie to Stardom: Watch the Original Music Video From 1969 NASA Digitizes 20,000 Hours of Audio from the Historic Apollo 11 Mission: Stream Them Free Online Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” and the Apollo 11 Moon Landing Turn 50 This Month: Celebrate Two Giant Leaps That Took Place 9 Days Apart is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

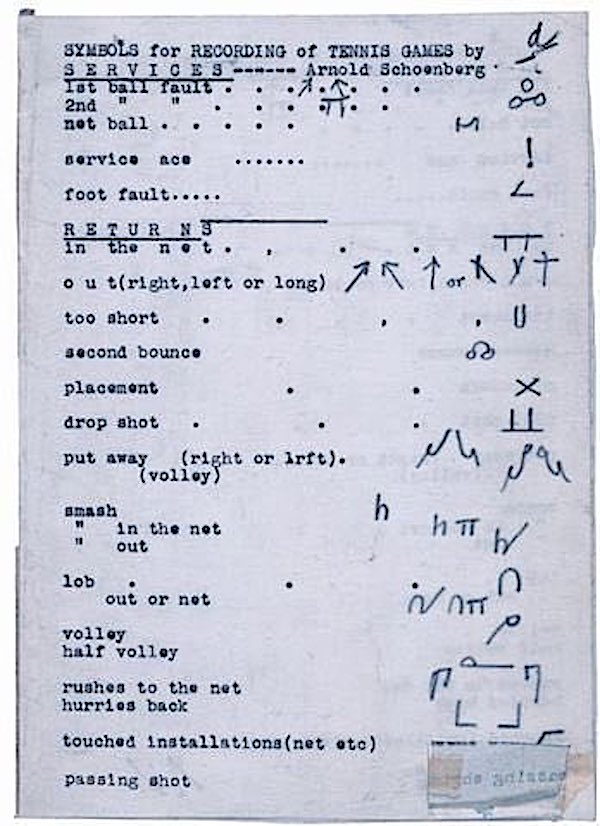

| 2:00p | Arnold Schoenberg, Avant-Garde Composer, Creates a System of Symbols for Notating Tennis Matches

This time each summer, as the conclusion of this year's fortnight-long championship at Wimbledon approaches, even the most private of the tennis enthusiasts in all of our circles make themselves known. Love of that particular game runs down all walks of life, but seems to exist in particularly high concentrations among cultural creators: not just writers like Martin Amis, Geoff Dyer, and David Foster Wallace, all of whose bodies of work contain eloquent thoughts on tennis, but composers of music as well. Take Arnold Schoenberg, who well into his old age continued not just to create the innovative music for which we remember him, but to spend time on the court as well. Though born in Vienna, Schoenberg eventually landed in the right place to enjoy tennis on the regular: southern California, to which he fled in 1933 after being informed of how inhospitable his homeland would soon become to persons of Jewish heritage. Few famous composers of that time had less in common than Schoenberg and George Gershwin, but their shared enjoyment of tennis made them into fast partners. According to Howard Pollack's life of Gershwin, fellow composer Albert Sendrey left a "revealing account" of one of the weekly matches between "the thirty-eight-year-old Gershwin and the sixty-two-year-old Schoenberg, contrasting the alternately 'nervous' and 'nonchalant,' 'relentless' and 'chivalrous' Gershwin, 'playing to an audience,' with the 'overly eager' and 'choppy' Schoenberg who 'has learned to shut his mind against public opinion.'" Any parallels between playing style and musical sensibility are, of course, entirely coincidental. The cerebral nature of Schoenberg's compositions may not suggest a temperament suited for physical activity of any kind, but even in Austria Schoenberg had been a keen sportsman. And as a fair few tennis-loving writers have explained, the game does possess an intellectual side, and one made more easily analyzable, at least in theory, by a system of Schoenberg's invention. "Toward the end of his life, Schoenberg — always fascinated by rules, analysis, and invention — would come up with a form of notation to transcribe the tennis matches of his athlete son Ronald," writes Mark Berry in Arnold Schoenberg. You can see this system laid out on the sheet above, recently posted on Twitter by Henry Gough-Cooper. The marks look vaguely similar to those of certain dance notation systems, a natural enough resemblance considering the kind of footwork tennis demands. But ideally, Schoenberg's notation would also have rendered a game of tennis as comprehensible as one of chess — another pursuit to which Schoenberg applied his mind. He came up with "an expanded four-player, ten-square version of the traditional game," writes Berry, "involving superpowers and lesser powers all compelled to forge alliances, with new pieces such as airplanes, tanks, submarines, and so forth." Schoenberg's "coalition chess," as he called it, seems to have caught on no more than his tennis notation system did. But then, the man who pioneered the twelve-tone technique never did go in for mass acceptance. via @NotationIsGreat and Henry Gough-Cooper on Twitter Related Content: Arnold Schoenberg Creates a Hand-Drawn, Paper-Cut “Wheel Chart” to Visualize His 12-Tone Technique Vi Hart Uses Her Video Magic to Demystify Stravinsky and Schoenberg’s 12-Tone Compositions John Coltrane Draws a Picture Illustrating the Mathematics of Music Bob Dylan and George Harrison Play Tennis, 1969 Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. Arnold Schoenberg, Avant-Garde Composer, Creates a System of Symbols for Notating Tennis Matches is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:47p | The Restoration of Rembrandt’s The Night Watch Begins: Watch the Painstaking Process On-Site and Online

Are collectibles markets driven by arbitrary standards? Of course. Just note the comparisons between the art world and world of vintage baseball cards. Don’t see any significant similarities? You must not be an economist. As Tim Schneider points out at Artnet, the two markets may be more alike than not, but they “diverge violently when it comes to the concept of restoration.” Baseball cards, no matter how tattered, stained, and torn, should never be tampered with to improve their condition one bit. One could say the same of many other “positional goods,” to use the properly economistic term. But economists don’t make categories with aesthetic criteria in mind, and most of us aren’t gallery owners, curators, or billionaire collectors, but lovers and appreciators of art. Do the vast majority of people who visit Rembrandt’s monumentally famous The Night Watch at the Rijksmuseum care about the fluctuations in the painting's market value? Likely not, especially since a work as treasured as the officially-titled Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq has no market value. "It will never be sold,” writes travel writer Kieran Meeke. The Night Watch is “literally ‘priceless.’ “Like many other such paintings in national collections, there is also no reason to insure it as it makes more financial sense to spend the premiums on improving security.” Other reasons to spend on security include the three violent attacks the painting has endured at the hands of angry and troubled would-be art assassins allowed to get too close. This damage, ranging from severe to mild, and the ravages of time, have also necessitated many expensive restoration efforts, and the latest undertaking is the biggest yet, especially since it has been turned into a heavily-promoted live event called “Operation Night Watch.” Last year, we brought you news of this upcoming opportunity to see the painting’s vibrant colors emerge from the accumulated grime; this month, the project began, with an introduction on Monday by museum director Taco Dibbets. This is “the largest research and restoration project ever for ‘the Night Watch,’” the Rijksmuseum reports, “and you can be part of it.” You do not need a ticket to the Netherlands, though if you buy one, you’ll also need to buy a ticket for entry to the museum, where the painting will be on full display during its restoration. If, however, you decide to watch from home, your seats are free. The project's name is only partly tongue-in-cheek. “It is like a military operation in the planning,” said Dibbets, and it has required the utmost precision and expert teams of restorers, data experts, art historians, and the professionals who moved the enormous painting into the glass case it will occupy during this intense period. The crew of restorers will work from digital images taken with a macro X-ray fluorescence scanner, a technique, says Dibbets, that allowed them to “make a full body scan” and “discover which pigments [Rembrandt] used.” This restoration project will greatly expand our understanding of the painting's creation, and renew our awe for its grandeur. There may be no way to calculate The Night Watch’s monetary value, outside of the unlikely event that the Rijksmuseum decides to sell, but what restorers, historians, gallery visitors—and millions of art lovers around the world, who only know the painting in reproductions—truly want to know is: what exactly did this beloved artwork look like when it was first made, and what might we have been missing in the almost 400 years we’ve been admiring it? We’ll get the chance to see not only the finished product of the restoration, but every painstaking step of the process as well. You can monitor the progress of the restoration online, and, further up, see a time-lapse video of the labor-intensive operation required to move the massive canvas. Related Content: 300+ Etchings by Rembrandt Now Free Online, Thanks to the Morgan Library & Museum What Makes The Night Watch Rembrandt’s Masterpiece Late Rembrandts Come to Life: Watch Animations of Paintings Now on Display at the Rijksmuseum Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Restoration of Rembrandt’s The Night Watch Begins: Watch the Painstaking Process On-Site and Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/07/10 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |