[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, July 18th, 2019

- Choose a topic you want to understand and start studying it.

- Pretend you’re teaching the idea to someone else. Write out an explanation on the paper…. Whenever you get stuck, go back and study.

- Finally do it again, but now simplify your language or use an analogy to make the point.

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | There’s a Tiny Art Museum on the Moon That Features the Art of Andy Warhol & Robert Rauschenberg

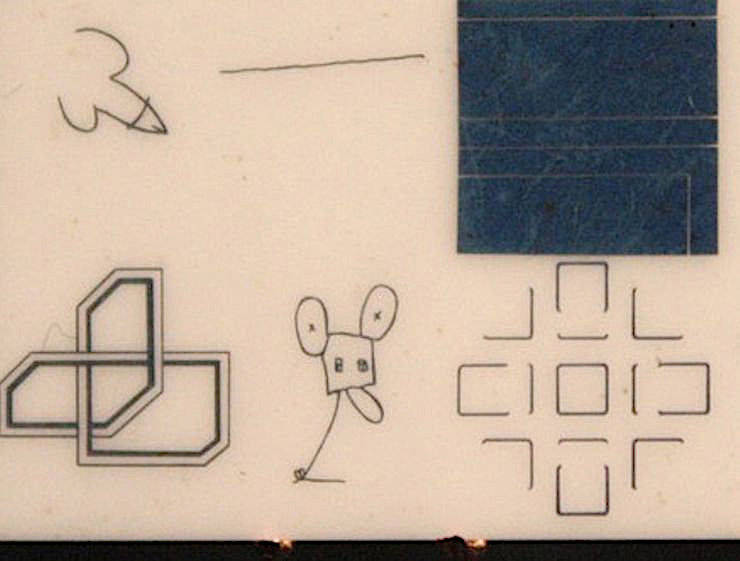

This week is the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, and though we have yet to send an artist into space (photographer Michael Najjar is apparently still training to become the first), there is a tiny art museum on the moon, and it’s been there since November 1969, four months after man set foot on the lunar service, and in the afterglow of that amazing summer. Don’t expect a walkable gallery, however. The museum is actually a ceramic wafer the size of a postage stamp, but what an impressive list: John Chamberlain, Forrest Myers, David Novros, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol. As you can see, the six kept it minimal. Rauschenberg drew a single line. Abstract artist Novros created a black square with intersecting white lines that look like a circuit board. Sculptor Chamberlain also created a geometric shape like circuitry. Oldenburg left his signature, which at the time resembled an old Mickey Mouse. Myers, who initiated the project, drew a “linked symbol.” And Andy Warhol drew a “stylized signature” but let’s be honest, it’s a penis. Yes, Warhol put a dick pic on the moon. The museum was not an officially sanctioned project. It had to be smuggled onto the Apollo 12 lunar lander. This took some doing and it started with Myers. He might not be as well known as his fellows, but Myers was one of the forces behind the Soho art scene in the ‘60s, who saw the industrial area blossom with artists looking for cheap rents and large spaces. Myers had been thinking about putting art on the moon, but all his entreaties to NASA were met with silence--neither a no nor a yes. It would have to be smuggled on board, he decided, but for such an operation, he’d need someone on the inside. Fortunately, there was a non-profit that was helping connect artists with engineers, called Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) and Rauschenberg was one of its founders. Through E.A.T., Myers met Bell Labs’ Fred Waldhauer who loved the moon museum project, and came up with the idea of the small wafers. Sixteen wafers were produced (other accounts say 20), one to go on Apollo 12, the others to go back to the artists (one now resides in MOMA’s collection). Waldhauer knew an engineer with Grumman who was working on the Apollo 12, and he agreed to sneak the ceramic wafer on board. But how would they know this ultra secret mission was accomplished? Two days before the Apollo launch, Myers received a telegram from Cape Canaveral: The artwork was not the only object sent to the moon on that mission. Engineers placed personal photos in the same place: in between the gold thermal insulation pads that would be shed when the lander left the moon’s surface. Only when Apollo 12’s re-entry capsule was on its way back to earth did Myers reveal to the press his successful stunt. However, unless we sent astronauts back to the exact same spot we don’t really know if the museum ever made its way there. Maybe it landed the wrong way up? Maybe other wafers moved in through gentrification, raised rents, and the moon museum had to move to Mars. We’ll never find out. Related Content: NASA Digitizes 20,000 Hours of Audio from the Historic Apollo 11 Mission: Stream Them Free Online Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW's Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here. There’s a Tiny Art Museum on the Moon That Features the Art of Andy Warhol & Robert Rauschenberg is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | An Animated Introduction to the Magical Fictions of Jorge Luis Borges "Reading the work of Jorge Luis Borges for the first time is like discovering a new letter in the alphabet, or a new note in the musical scale," writes the BBC's Jane Ciabattari. Borges' essay-like works of fiction are "filled with private jokes and esoterica, historiography and sardonic footnotes. They are brief, often with abrupt beginnings." His "use of labyrinths, mirrors, chess games and detective stories creates a complex intellectual landscape, yet his language is clear, with ironic undertones. He presents the most fantastic of scenes in simple terms, seducing us into the forking pathway of his seemingly infinite imagination." If that sounds like your idea of good read, look a little deeper into the work of Argentina's most famous literary figure through the animated TED-Ed lesson above. Mexican writer and critic Ilan Stavans, the lesson's creator, begins his introduction to Borges by describing a man who "not only remembers everything he has ever seen, but every time he has seen it in perfect detail." Many of you will immediately recognize Funes the Memorious, the star of Borges' 1942 story of the same name — and those who don't will surely want to know more about him. Stavans goes on to describe a library "built out of countless identical rooms, each containing the same number of books of the same length," that as a whole "contains every possible variation of text." He also mentions a rumored "lost labyrinth" that turns out to be "not a physical maze but a novel," and a novel that reveals the identity of the real labyrinth: time itself. Borges enthusiasts know which places Stavans is talking about, meaning they know in which of Borges' stories — which their author, sticking to a word from his native Spanish, referred to as ficciones — they originate. But though "The Library of Babel" (which in recent years has taken a digital form online) and "The Garden Forking Paths" count as two particularly notable examples of what Stavans calls "Borges' many explorations of infinity," he found so many ways to explore that subject throughout his writing career that his literary output functions as a consciousness-altering substance. It does to the right readers, that is, a group that includes such other mind-bending writers as Umberto Eco, Roberto Bolaño, and William Gibson, none of whom were quite the same after they discovered the ficciones. Behold Borges' mirrors, mazes, tigers, and chess games yourself — thereby catching a glimpse of infinity — and you, too, will never be able to return to the reader you once were. Not that you'd want to. Related Content: Jorge Luis Borges Explains The Task of Art Jorge Luis Borges’ 1967-8 Norton Lectures On Poetry (And Everything Else Literary) An Animated Introduction to H.P. Lovecraft and How He Invented a New Gothic Horror Why Should You Read James Joyce’s Ulysses?: A New TED-ED Animation Makes the Case Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. An Animated Introduction to the Magical Fictions of Jorge Luis Borges is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 4:15p | Introducing Pretty Much Pop (A Culture Podcast): Episode 1 – Pop Culture vs. High Culture

What is pop culture? Does it make sense to distinguish it from high culture, or can something be both? Open Culture is pleased to curate a new podcast covering all things entertainment: TV, movies, music, novels, video games, comics, novels, comedy, theater, podcasts, and more. Pretty Much Pop is the invention of Mark Linsenmayer (aka musician Mark Lint), creator of The Partially Examined Life Philosophy Podcast and Nakedly Examined Music. Mark is joined by co-hosts Erica Spyres, an actor and musician who's appeared on Broadway and plays classical and bluegrass violin, and Brian Hirt, a science-fiction writer/linguistics major who collaborates with his brother on the Constellary Tales magazine and podcast. For this introductory discussion touching on opera, The Beatles, Fortnite, 50 Shades of Grey, reality TV, and more, our hosts are joined by the podcast's audio editor Tyler Hislop, aka Sacrifice MC. Some of the articles brought in the discussion are: "The Long War Between Highbrow and Lowbrow" by Noah Berlatsky from the Pacific Standard (2017) "Pop Culture's Progress Toward Tragedy" by Titus Techera from the National Review (2019) Read more about the 1895 silent film that featured a train coming right out of the screen, sending people screaming in terror. Here's more about the opening of Stravinsky's "Rite of Spring" at which spectators rioted. You may also enjoy episode 137 of The Partially Examined Life about the tastes of social classes that analyzes Pierre Bourdieu. Also see episode 193 on liberal education and the idea of a "canon" of essential, high-culture works. The opening music is by Mark (guitars, cellos, djembe) and Erica (violins). The podcast logo is by Ken Gerber. The ending song was written by Mark just for this episode. It's called "High Rollin' Cult," and features Erica on violin and harmonies. For more information on the podcast, visit prettymuchpop.com or look for the podcast soon on Apple Podcasts. To support this effort (and immediately get access to four episodes plus bonus content), make a small, recurring donation at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. Introducing Pretty Much Pop (A Culture Podcast): Episode 1 – Pop Culture vs. High Culture is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:00p | Buckminster Fuller Tells the World “Everything He Knows” in a 42-Hour Lecture Series (1975) [Error: Irreparable invalid markup ('<div [...] http://cdn8.openculture.com/>') in entry. Owner must fix manually. Raw contents below.] <div class="oc-ratio-embed ratio75" http://cdn8.openculture.com/="http://cdn8.openculture.com/">

<p>History seems to have settled Buckminster’s Fuller’s reputation as a man ahead of his time. He inspires short, witty popular videos like YouTuber Joe Scott’s “<a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IrVcDxSpwGM">The Man Who Saw The Future</a>,” and the ongoing legacy of the <a href="https://www.bfi.org/">Buckminster Fuller Institute</a> (BFI), who note that “Fuller’s ideas and work continue to influence new generations of designers, architects, scientists and artists working to create a sustainable planet.”</p>

<p>Brilliant futurist though he was, Fuller might also be called the man who saw the present and the past—as much as a single individual could seemingly hold in their mind at once. He was “a man who is intensely interested in almost everything,” wrote Calvin Tomkins at <a href="https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1966/01/08/in-the-outlaw-area"><em>The New</em> Yorker in 1965</a>, the year of Fuller’s 70th birthday. Fuller was as eager to pass on as much knowledge as he could collect in his long, productive career, spanning his early epiphanies in the 1920s to his final public talks in the early 80s.</p>

<div class="oc-ratio-embed ratio75" />

<p>“The somewhat overwhelming effect of a Fuller monologue,” wrote Tomkins, “is well known today in many parts of the world.” His lectures leapt from subject to subject, incorporating ancient and modern history, mathematics, linguistics, architecture, archaeology, philosophy, religion, and—in the example Tomkins gives—“irrefutable data on tides, prevailing winds,” and “boat design.” His discourses issue forth in wave after wave of information.</p>

<div class="oc-center-da">

</div>

<p>Fuller could talk at length and with authority about virtually anything—especially about himself and his own work, in his own special jargon of “unique Bucky-isms: special phrases, terminology, unusual sentence structures, etc.,” writes BFI. He may not always have been particularly humble, yet he spoke and wrote with a lack of prejudice and an open curiosity and that is the opposite of arrogance. Such is the impression we get of Fuller in the series of talks he recorded ten years after Tomkin’s <em>New Yorker </em>portrait.</p>

<div class="oc-ratio-embed ratio75" />

<p>Made in January of 1975, <em><a href="https://archive.org/details/buckminsterfuller">Buckminster Fuller: Everything I Know</a> </em>captured Fuller’s “entire life’s work” in 42 hours of “thinking out loud lectures [that examine] in depth all of Fuller’s major inventions and discoveries from the 1927 Dymaxion house, car and bathroom, through the Wichita House, geodesic domes, and tensegrity structures, as well as the contents of Synergetics. Autobiographical in parts, Fuller recounts his own personal history in the context of the history of science and industrialization.”</p>

<p>He begins, however, in his first lecture at the top, not with himself, but with his primary subject of concern: “all humanity,” a species that begins always in nakedness and ignorance and manages to figure it out “entirely by trial and error,” he says. Fuller marvels at the advances of “early Hindu and Chinese” civilizations—as he had at the Maori in Tomkin’s anecdote, who “had been among the first peoples to discover the principles of celestial navigation” and “found a way of sailing around the world… at least ten thousand years ago.”</p>

<div class="oc-ratio-embed ratio75" />

<p>The leap from ancient civilizations to “what is called World War I” is “just a little jump in information,” he says in his first lecture, but when Fuller comes to his own lifetime, he shows how many “little jumps” one human being could witness in a lifetime in the 20th century. “The year I was born Marconi invented the wireless,” says Fuller. “When I was 14 man did get to the North Pole, and when I was 16 he got to the South Pole.”</p>

<p>When Fuller was 7, “the Wright brothers suddenly flew,” he says, “and my memory is vivid enough of seven to remember that for about a year the engineering societies were trying to prove it was a hoax because it was absolutely impossible for man to do that.” What it showed young Bucky Fuller was that “impossibles are happening.” If Fuller was a visionary, he redefined the word—as a term for those with an expansive, infinitely curious vision of a possible world that already exists all around us.</p>

<p>See Fuller’s complete lecture series, <a href="https://archive.org/details/buckminsterfuller"><em>Everything I Know</em>, at the Internet Archive</a>, and <a href="https://www.bfi.org/about-fuller/resources/everything-i-know">read edited transcripts of his talks at the Buckminster Fuller Institute</a>.</p>

<p><a href="https://archive.org/details/buckminsterfuller"><em>Everything I Know</em></a> will be added to our collection, <span style="font-weight: 400;"><a href="http://www.openculture.com/freeonlinecourses">1,300 Free Online Courses from Top Universities</a>.</span></p>

<p><strong>Related Content:</strong></p>

<p><a href="http://www.openculture.com/2017/05/a-three-minute-introduction-to-buckminster-fuller-one-of-the-20th-centurys-most-productive-design-visionaries.html">A Three-Minute Introduction to Buckminster Fuller, One of the 20th Century’s Most Productive Design Visionaries</a></p>

<p><a href="http://www.openculture.com/2019/03/buckminster-fuller-on-technology-and-useless-jobs.html">Buckminster Fuller Rails Against the “Nonsense of Earning a Living”: Why Work Useless Jobs When Technology & Automation Can Let Us Live More Meaningful Lives</a></p>

<p><a href="http://www.openculture.com/2018/10/buckminster-fuller-creates-striking-posters-inventions.html">Buckminster Fuller Creates Striking Posters of His Own Inventions</a></p>

<p><a href="http://www.openculture.com/2018/12/buckminster-fuller-documented-his-life-every-15-minutes-resulting-in-the-massive-dymaxion-chronofile.html">Buckminster Fuller Documented His Life Every 15 Minutes, from 1920 Until 1983</a></p>

<p><em><a href="http://about.me/jonesjoshua">Josh Jones</a> is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at <a href="https://twitter.com/jdmagness">@jdmagness</a></em></p>

<!-- permalink:http://www.openculture.com/2019/07/buckminster-fuller-tells-the-world-everything-he-knows-in-a-42-hour-lecture-series-1975.html--><p><a rel="nofollow" href="http://www.openculture.com/2019/07/buckminster-fuller-tells-the-world-everything-he-knows-in-a-42-hour-lecture-series-1975.html">Buckminster Fuller Tells the World “Everything He Knows” in a 42-Hour Lecture Series (1975)</a> is a post from: <a href="http://www.openculture.com">Open Culture</a>. Follow us on <a href="https://www.facebook.com/openculture">Facebook</a>, <a href="https://twitter.com/#!/openculture">Twitter</a>, and <a href="https://plus.google.com/108579751001953501160/posts">Google Plus</a>, or get our <a href="http://www.openculture.com/dailyemail">Daily Email</a>. And don't miss our big collections of <a href="http://www.openculture.com/freeonlinecourses">Free Online Courses</a>, <a href="http://www.openculture.com/freemoviesonline">Free Online Movies</a>, <a href="http://www.openculture.com/free_ebooks">Free eBooks</a>, <a href="http://www.openculture.com/freeaudiobooks">Free Audio Books</a>, <a href="http://www.openculture.com/freelanguagelessons">Free Foreign Language Lessons</a>, and <a href="http://www.openculture.com/free_certificate_courses">MOOCs</a>.</p>

<div class="feedflare">

<a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=j2-eKgIqSrw:VJHjDSOcVL0:yIl2AUoC8zA"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?d=yIl2AUoC8zA" border="0"></img></a> <a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=j2-eKgIqSrw:VJHjDSOcVL0:V_sGLiPBpWU"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?i=j2-eKgIqSrw:VJHjDSOcVL0:V_sGLiPBpWU" border="0"></img></a> <a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=j2-eKgIqSrw:VJHjDSOcVL0:gIN9vFwOqvQ"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?i=j2-eKgIqSrw:VJHjDSOcVL0:gIN9vFwOqvQ" border="0"></img></a> <a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=j2-eKgIqSrw:VJHjDSOcVL0:qj6IDK7rITs"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?d=qj6IDK7rITs" border="0"></img></a> <a href="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?a=j2-eKgIqSrw:VJHjDSOcVL0:I9og5sOYxJI"><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~ff/OpenCulture?d=I9og5sOYxJI" border="0"></img></a>

</div><img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~r/OpenCulture/~4/j2-eKgIqSrw" height="1" width="1" alt="" /> |

| 7:00p | Richard Feynman’s Technique for Learning Something New: An Animated Introduction I sometimes wonder: why do people post amateur repair videos, made with smartphones in kitchens and garages, with no obvious commercial value and, often, a level of expertise just minimally above that of their viewers? Then I remember Richard Feynman’s practical advice for how to learn something new—prepare to teach it to somebody else. The extra accountability of making a public record might provide added motivation, though not nearly to the degree of making teaching one's profession. Nobel-winning physicist Feynman spent the first half of his academic career working on the Manhattan Project, dodging J. Edgar Hoover's FBI at the beginning of the Cold War, and making major breakthroughs in quantum mechanics. But he has become as well-known for his teaching as for his historic scientific role, thanks to the enormously popular series of physics lectures he developed at Caltech; his funny, accessible, best-selling books of essays and memoirs; and his willingness to be an avuncular public face for science, with a knack for explaining things in terms anyone can grasp. Feynman revealed that he himself learned through what he called a "notebook technique," an exercise conducted primarily on paper. Yet the method came out of his pedagogy, essentially a means of preparing lecture notes for an audience who know about as much about the subject as you did when you started studying it. In order to explain it to another, you must both understand the subject yourself, and understand what it's like not to understand it. Learn Feynman’s method for learning in the short animated video above. You do not actually need to teach, only pretend as if you're going to—though preparing for an actual audience will keep you on your toes. In brief, the video summarizes Feynman’s method in a three-step process: Get ready to start your YouTube channel with homemade language lessons, restoration projects, and/or cooking videos. You may not—nor should you, perhaps—become an online authority, but according to Feyman, who learned more in his lifetime than most of us could in two, you’ll come away greatly enriched in other ways. Related Content: The Drawings & Paintings of Richard Feynman: Art Expresses a Dramatic “Feeling of Awe” Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Richard Feynman’s Technique for Learning Something New: An Animated Introduction is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/07/18 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |