[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Friday, July 19th, 2019

| Time | Event |

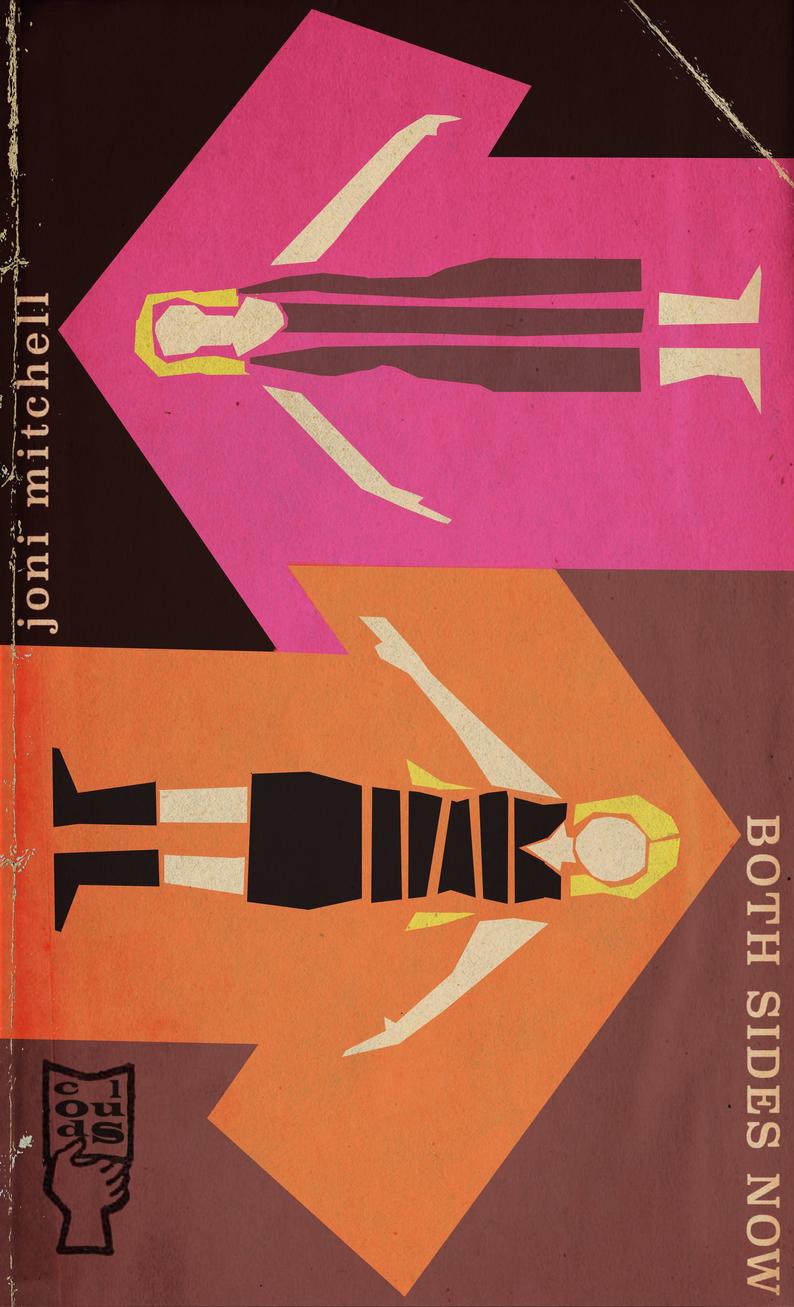

| 8:00a | Songs by Joni Mitchell Re-Imagined as Pulp Fiction Book Covers & Vintage Movie Posters

Joni Mitchell has been showered with tributes of late, many of them connected to her all-star 75th birthday concert last November. The silky voiced Seal, who credits Mitchell with inspiring him to become a musician, soaring toward heaven on "Both Sides Now"… "A Case Of You" as a duet for fellow Newport Folk Festival alums Kris Kristofferson and Brandi Carlile…. Chaka Khan injecting a bit of funk into "Help Me," a tune she’s been covering for 20 some years... They’re moving and beautiful and sensitive, but given that Mitchell's the one behind the immortal lyric “laughing and crying, you know it's the same release…,” shouldn’t someone aim for the funny bone? Mix things up a little? Enter Todd Alcott, who’s been delighting us all year with his “mid-century mashups,” an irresistible combination of vintage paperback covers, celebrity personae, and iconic lyrics from the annals of rock and pop. His homage to "Help Me," above, is decidedly on brand. The lurid 1950s EC horror comic-style graphics confer a dishy naughtiness that was—no disrespect—rather lacking in the original. Perhaps Mitchell would approve of these monkeyshines? A 1991 interview with Rolling Stone’s David Wild suggests that she would have at some point in her life:

Alcott honors the introvert by rendering "Both Sides Now" as an angsty-looking volume of 60s-era poetry from the imaginary publishing house Clouds.

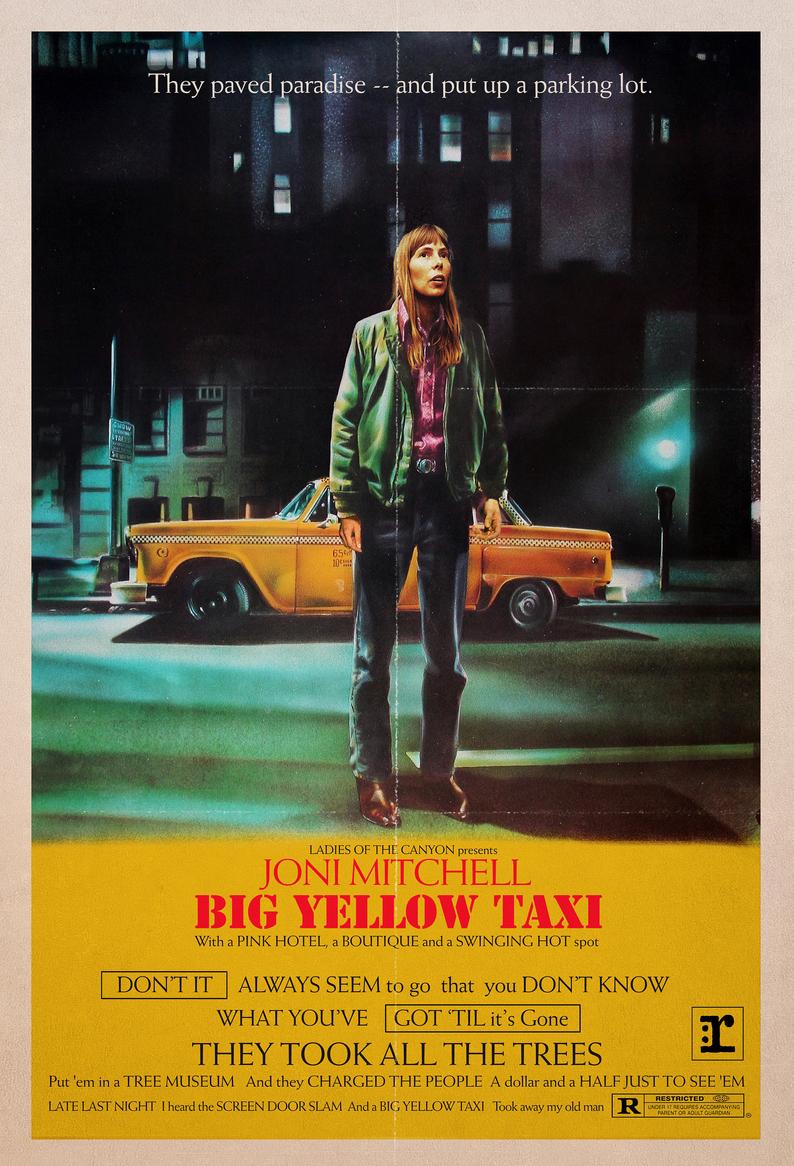

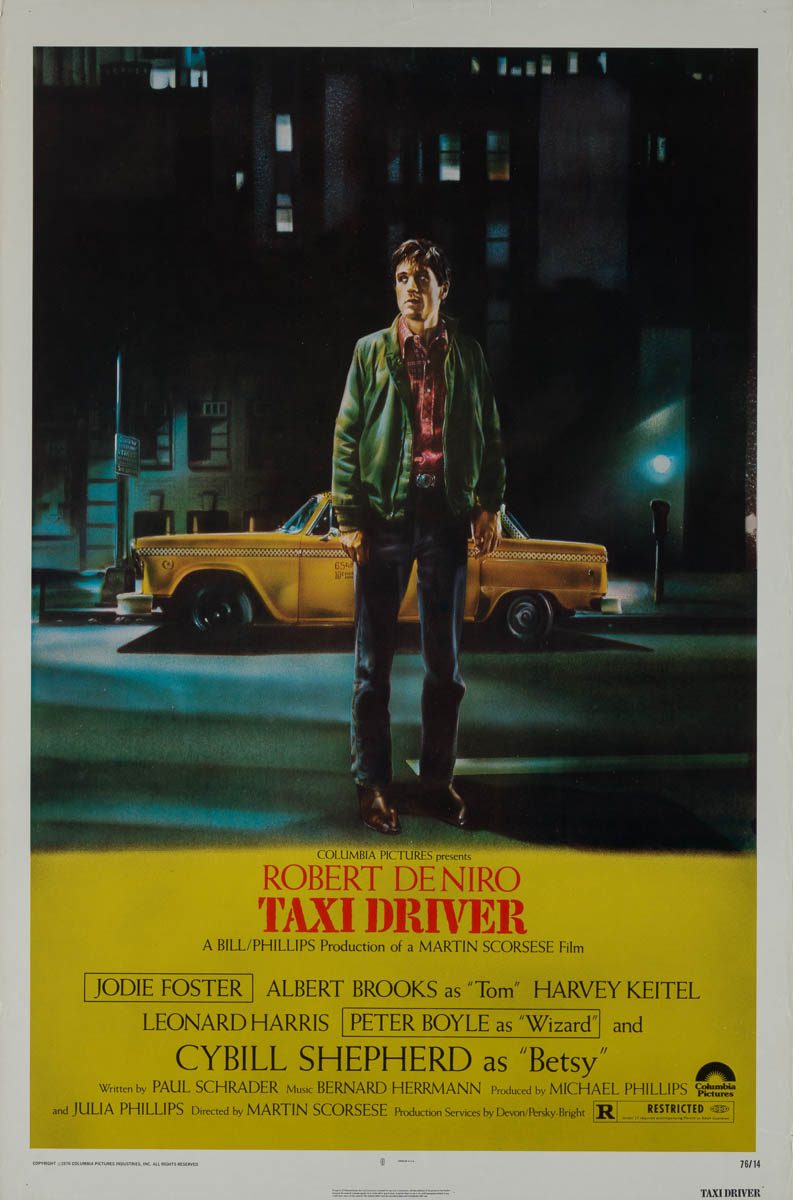

"Big Yellow Taxi" carries Alcott from the bookshelf to the realm of the movie poster. The lyrics are definitely the star here, but it's fun to note just how much mileage he gets out of the floating text boxes that were a strangely random-feeling feature of the original. Also "Ladies of the Canyon" is a great producer's credit. Given Alcott’s own screenwriting credits on IMDB, perhaps we could convince him to mash a bit of Joni’s sensibility into some of Paul Schrader’s grimmest Taxi Driver scenes… That said, it's worth remembering that Alcott's creations are loving tributes to the artists who matter most to him. As he told Open Culture:

See all of Todd Alcott’s work here. (Please note that this is his official sales site… beware of imposters selling quickie knock-offs of his designs on eBay and Facebook.) Find other posts featuring his work in the Relateds below. Related Content: Songs by David Bowie, Elvis Costello, Talking Heads & More Re-Imagined as Pulp Fiction Book Covers Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Join her in NYC on Monday, September 9 for a new season of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Songs by Joni Mitchell Re-Imagined as Pulp Fiction Book Covers & Vintage Movie Posters is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | Alexis de Tocqueville’s Prediction of How American Democracy Could Lapse Into Despotism, Read by Michel Houellebecq Michel Houellebecq's third novel Platform, which involves a terrorist bombing in southeast Asia, came out the year before a similar real-life incident occurred in Thailand. His seventh novel Submission, about the conversion of France into a Muslim country, came out the same day as the massacre at the offices of Islam-provoking satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo. His most recent novel Serotonin, in which farmers violently revolt against the French state, happened to come out in the early stages of the populist "yellow vest" movement. Houellebecq has thus, even by some of his many detractors, been credited with a certain prescience about the social and political dangers of the world in which we live today. So too has a countryman of Houellebecq's who did his writing more than 150 years earlier: Alexis de Tocqueville, author of Democracy in America, the enduring study of that then-new country and its daringly experimental political system. And what does perhaps France's best-known living man of letters think of Tocqueville, one of his best-known predecessors? "I read him for the first time long ago and really found it a bit boring," Houellebecq says in the interview clip above, with a flatness reminiscent of his novels' disaffected narrators. "Then I tried again two years ago and I was thunderstruck." As an example of Tocqueville's clear-eyed assessment of democracy, Houellebecq reads aloud this passage about its potential to turn into despotism:

Being a writer, Houellebecq naturally points out the deftness of Tocqueville's style: "It's magnificently punctuated. The distribution of colons and semicolons in the sections is magnificent." But he also has comments on the passage's philosophy, pronouncing that it "contains Nietzsche, only better." The operative Nietzschean concept here is the "last man," described in Thus Spoke Zarathustra as the presumable end point of modern society. If conditions continue to progress in the way they have been, each and every human being will become this last man, a weak, comfortable, complacent individual with nothing left to fight for, who desires nothing more than his small pleasure for the day, his small pleasure for the night, and a good sleep. Safe to say that neither Nietzsche nor Tocqueville looked forward, nor does Houellebecq look forward, to the world of enervated last men into which democracy could deliver us. Houellebecq also reads aloud another passage from Democracy in America, one that now appears on the Wikipedia page for soft despotism, describing how a democratic government might gain absolute power over its people without the people even noticing:

"A lot of what I've written could be situated within this scenario," Houellebecq says, adding that in his generation the "definitive transformation of society into individuals" has been more complete than Tocqueville or Nietzsche would have imagined. In addition to lacking a family, Houellebecq (whose second novel was titled Atomized) also mentions having "the impression of being caught up in a network of complicated, minute, and stupid rules" as well as "of being herded toward a uniform kind of happiness, toward a happiness which doesn't really make me happy." In the end, adds Houellebecq, the aristocratic Tocqueville "is in favor of the development of democracy and equality, while being more aware than anyone else of its dangers." That the 19th-century America Tocqueville knew avoided them he credited to the "habits of the heart" of the American people. We citizens of democratic countries, whichever democratic country we live in, would do well to ask where the habits of our own hearts will lead us next. Related Content: How to Know if Your Country Is Heading Toward Despotism: An Educational Film from 1946 George Orwell’s Final Warning: Don’t Let This Nightmare Situation Happen. It Depends on You! The History of Western Social Theory, by Alan MacFarlane, Cambridge University Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. Alexis de Tocqueville’s Prediction of How American Democracy Could Lapse Into Despotism, Read by Michel Houellebecq is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 4:50p | Every Harrowing Second of the Apollo 11 Landing Revisited in a New NASA Video: It Took Place 50 Years Ago Today (July 20, 1969) The idea that human beings might not only fly to the moon, but land on its puckered surface and walk around, seemed like an absolute fantasy for nearly all of human history. In the exactly fifty years since that that very thing happened, "moon shot" has become an almost commonplace reference for grand, historic gestures. “Fifty years after Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, planted an American flag, and flew home,” writes Alex Davies at Wired, “the term moon shot has become shorthand for trying to do something that’s really hard and maybe a bit crazy.” The problem with this, Davies argues, is that the all-eggs-in-one-basket approach does not apply today's most pressing, yet most nebulous and global, problems. A “moon shot” climate initiative suffers from a lack of specificity. What exactly would it target? How would it measure success or failure in an unambiguous way when the problem permeates the economy, energy, agriculture, manufacturing, government...? A very different kind of thinking is required. Maybe the dualisms of the Cold War made some things simpler, in a way. In 1961, John F. Kennedy’s famous articulation of “the goal,” as he put it, could not have been more clear: “landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth.” You either achieve this, or you don’t. There are no half-measures, and no confusion about what constitutes success. Which brings us to another problem with turning “moon shot” into a cliché for doing something hard. We forget just how damned hard it actually was. Landing Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and pilot Michael Collins on the moon required an expenditure unthinkable today: “NASA spent $25 billion on the Apollo program,” Davies points out, “more than $150 billion in today’s dollars.” The U.S. may spend almost seven times that on its military in a year, but it’s unthinkable that this nation, or any other, would invest Apollo dollars in a completely unsure thing, with no immediate potential for control or exploitation. The same might be said of major corporations. The spacefaring ambitions of today’s titans seem conservative by 1961 standards: “More than 400,000 Americans worked on [Apollo 11] in some capacity, nearly all of them in private industry,” writes Davies. The project absolutely depended on this coordinated, collective level of human ingenuity and expertise because the total computing power of NASA was several millions of times less than that of a smartphone. From the human “computers” who plotted Apollo 11’s course, to the astronauts who flew the craft, humans not only designed, monitored, and executed the mission, but they also had to improvise when things went wrong. And they did, in some terrifying, life-threatening ways. “The problems began immediately upon separation from the Command Module in which Armstrong, Aldrin and Michael Collins had ridden to the moon,” explains Rod Pyle at Space.com—but, so too did the problem-solving. To get a better sense of why the endeavor was so earthshaking, and how it almost didn’t happen, watch the video above, “Apollo 11: The Complete Descent.” Part of NASA’s Apollo Flight Journal collection, the 20-minute narrated documentary of the descent and landing provides a "detailed account of every second of the Apollo 11 descent and landing." It “combines data from the onboard computer for altitude and pitch angle, 16mm film that was shot throughout the descent at 6 frames per second,” and audio transmissions from the astronauts and mission control. “Most people knew that going to the moon was risky,” Pyle writes, “but few, very few, knew the scope of the dangers that the crew faced.” Fifty years later, we can almost—with only the devices in our pockets—see and hear the original moon shot the way those first few did. Related Content: NASA Digitizes 20,000 Hours of Audio from the Historic Apollo 11 Mission: Stream Them Free Online Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Every Harrowing Second of the Apollo 11 Landing Revisited in a New NASA Video: It Took Place 50 Years Ago Today (July 20, 1969) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/07/19 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |