[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Friday, August 2nd, 2019

- “HBO’s Chernobyl Isn’t Just Historical Drama, It’s Straight-Up Horror” by Renaldo Matadeen

- “Top UCLA Doctor Denounces HBO’s “Chernobyl” As Wrong And “Dangerous” by Michael Shellenberger

- “What HBO’s ‘Chernobyl’ Got Right, and What It Got Terribly Wrong” by Masha Gessen

- “What Watching “Misery Porn” Shows Like ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ Does To Your Mental Health” by Louisa Ballhaus

- “The Misery Porn of Game of Thrones Isn’t Profound. It’s Just Miserable” by Sam Brooks

- The TV Tropes page for “Based on a True Story”

| Time | Event |

| 7:01a | Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #4 – HBO’s “Chernobyl”: Why Do We Enjoy Watching Suffering?

On the HBO mini-series Chernobyl. Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt first get into the various degrees of looseness in something’s being “based on a true story.” Does it matter if it’s been changed to be more dramatic? We then consider the show as entertainment: Why do people enjoy witnessing suffering? Why might a drama work (or not) for you? We also touch on Game of Thrones, The Killing, God Is Dead, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Big Little Lies, Schindler’s List, Vice, Ip Man, and more. Some of the articles we looked at to prepare: Our Lucy Lawless interview will be out next week! Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is a member of the The Partially Examined Life Podcast Network. Get more at prettymuchpop.com. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, or Google Play. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is produced by the Partially Examined Life Podcast Network. This episode includes bonus content that you can only hear by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #4 – HBO’s “Chernobyl”: Why Do We Enjoy Watching Suffering? is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00a | Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” Sung in the Style of David Bowie If you like what Anthony Vincent has to offer here, there's more where that came from. Don't miss his other viral video, "Enter Sandman in 20 Styles," which features Metallica's 1998 hit sung in the style of Stevie Wonder, The Police, The Doors and much more. Would you like to support the mission of Open Culture? Please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. Also consider following Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and sharing intelligent media with your friends. Or sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” Sung in the Style of David Bowie is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:00p | The Unexpected Ways Eastern Philosophy Can Make Us Wiser, More Compassionate & Better Able to Appreciate Our Lives I feel compelled to start this post with a disclaimer: do not take the eight-and-a-half-minute video above, "Six Ideas from Eastern Philosophy" from Alain de Botton’s School of Life series, as an authoritative statement on Eastern Philosophy. Not that you would, or that de Botton makes such a claim, but in an age of uncritical overconsumption, infinite scrolling, and individually-wrapped explainers, it seems worth the reminder. No tradition—and certainly not one as incalculably rich, deep, and ancient as the schools of thought summed up as “Eastern Philosophy”—can be paraphrased in an animated list. Think of “Six Ideas from Eastern Philosophy” as a teaser. If you’ve resigned yourself to the fact that suffering is ever-present and universal—the first idea on de Botton’s list and the Buddha’s first Noble Truth—you might love… or make a good faith effort to appreciate… The Middle Length Discourses, the Shobogenzo, the poetry and songs of Han Shan and Milarepa, or the thousands of translations, commentaries, adaptations, and etcetera about them. But the video isn't about famous texts. The logocentric characterization of philosophy as only writing persists, despite its serious limitations. In many Eastern traditions, writing and study are only one part of complex religious practices. The first two ideas on de Botton’s list come from early Indian Buddhism; the third from Chinese Chan Buddhism, the fourth and fifth are Daoist concepts; and the sixth, kintsugi, comes from Japanese Zen. De Botton’s title is misleading. As he goes on to show, in brief, but with vivid examples and comparisons, these are not “ideas” in the broadly Platonic sense of pure abstractions but formalized ways of being with others and being alone, of being with objects and natural formations that embody ethical ideals of balance, equanimity, contentment, kindness, care, and deep appreciation for art and nature, with all their imperfections and disappointments. Can we make much sense of the adoration of the bodhisattva Guanyin (whom de Botton compares to the Virgin Mary) if we never visit one of her temples or call for her compassionate aid? Can we study the subtleties of bamboo without bamboo? Can we grasp the Four Noble Truths if we can’t sit still long enough for serious self-reflection? Sometimes the practices, landscapes, and iconographies of Eastern philosophy do not seem separable from ideas about them. If there’s a bow to tie on de Botton’s summary, maybe it’s this: from these Buddhist and Daoist perspectives, the endless bifurcations of Western thought are illusory. Pain, imperfection, and uncertainly are inevitable and not to be feared but compassionately accepted. And philosophy is something that happens in the body and mind together, an idea certainly not alien to the walking thinkers of the West. Related Content: Eastern Philosophy Explained with Three Animated Videos by Alain de Botton’s School of Life What Is a Zen Koan? An Animated Introduction to Eastern Philosophical Thought Experiments Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him The Unexpected Ways Eastern Philosophy Can Make Us Wiser, More Compassionate & Better Able to Appreciate Our Lives is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

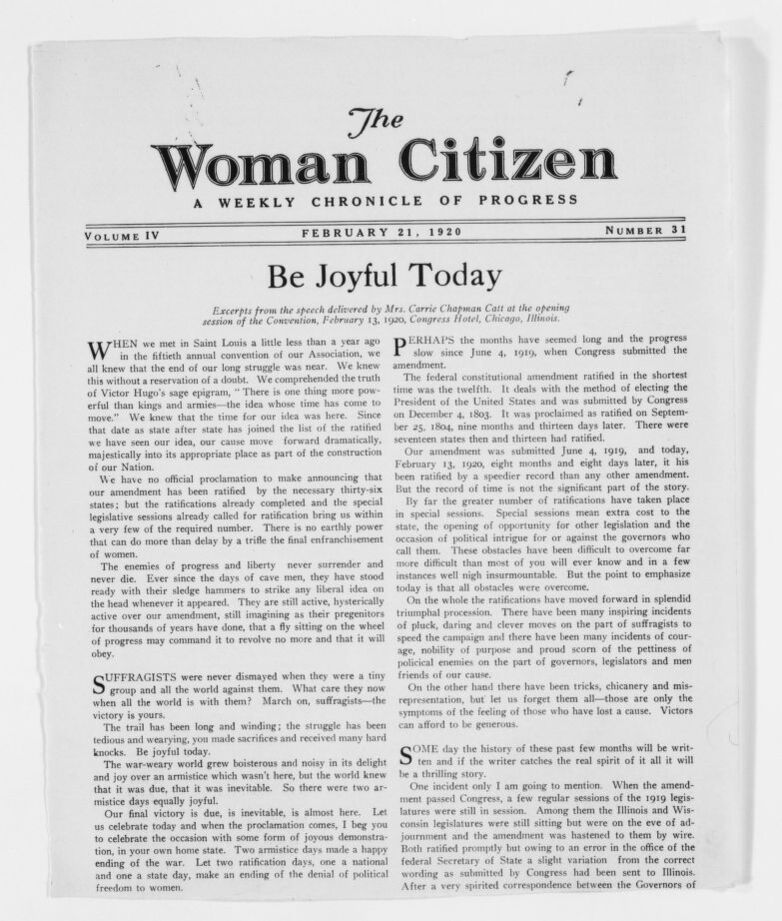

| 7:00p | The Library of Congress Digitizes Over 16,000 Pages of Letters & Speeches from the Women’s Suffrage Movement, and You Can Help Transcribe Them

“Democracy may not exist,” Astra Taylor declares in the title of her new book, “but we’ll miss it when it’s gone.” This inherent paradox, she argues, is not fatal, but a tension with which each era’s democratic movements must wrestle, in messy struggles against inevitable opposition. “Perfect democracy… may not in fact exist and never will, but that doesn’t mean we can’t make progress toward it, or that what there is of it can’t disappear.” Taylor is upfront about “democracy’s dark history, from slavery and colonialism to facilitating the emergence of fascism.” But she is equally celebratory of its successes—moments when those who were denied rights marshaled every means at their disposal, from lobbying campaigns to confrontational direct action, to win the vote and better the lives of millions. For all its imperfections, the women’s suffrage movement of the 19th and early 20th century did just that. It did so—even before electronic mass communication systems—by building international activist networks and forming national associations that took highly-visible action for decades until the 19th Amendment passed in 1920. We can learn how this all came about from the sources themselves, through the “letters, speeches, newspaper articles, personal diaries, and other materials from famed suffragists like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.” So reports Mental Floss, describing the Library of Congress’ digital collection of suffragist papers, which includes dozens of famous and less famous activist voices. In one example of both international cooperation and international tension, Carrie Chapman Catt, Anthony’s successor (see a published excerpt of one of her speeches below), describes her experience at the Congress of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in Rome. “A more unpromising place for a Congress I never saw,” she wrote, dismayed. Maybe despite herself she reveals that the differences might have been cultural: “The Italian women could not comprehend our disapproval.”

The fractious, often disappointing, relationships between the larger international women’s suffrage movement, the African American women’s suffrage movement, and mostly male Civil Rights leaders in the U.S. are represented by the diaries. letters, notebooks, and speeches of Mary Church Terrell, “a founder of the National Association of Colored Women. These documents shed light on minorities’ laborious suffrage struggles and her own dealings with Civil Rights figures like W.E.B. Du Bois." (Terrell became an activist in 1892 and lived to fight against Jim Crow segregation in the early 1950s.) The collection includes “some 16,000 historic papers related to the women’s rights movement alone.” All of them have been digitally scanned, and if you’re eager to dig into this formidable archive, you’re in luck. The Library of Congress is asking for help transcribing so that everyone can read these primary sources of democratic history. So far, reports Smithsonian, over 4200 documents have been transcribed, as part of a larger, crowdsourced project called By the People, which has previously transcribed papers from Abraham Lincoln, Clara Barton, Walt Whitman, and others. Rather than focusing on an individual, this project is inclusive of what is arguably the main engine of democracy: large-scale social movements—paradoxically the most democratic means of claiming individual rights. Enter the impressive digital collection “Suffrage: Women Fight for the Vote” here, and, if you’re moved by civic duty or scholarly curiosity, sign up to transcribe. via Mental Floss Related Content: Odd Vintage Postcards Document the Propaganda Against Women’s Rights 100 Years Ago The Library of Congress Makes Thousands of Fabulous Photos, Posters & Images Free to Use & Reuse Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness. The Library of Congress Digitizes Over 16,000 Pages of Letters & Speeches from the Women’s Suffrage Movement, and You Can Help Transcribe Them is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00p | Why a Cat Always Lands on Its Feet: How a French Scientist Used Photography to Solve the Problem in 1894 In the era of the CATS trailer and #catsofinstagram, it’s easy to forget that scientific research is what originally convinced our feline friends to allow their images to be captured and disseminated. An anonymous white French pussy took one for the team in 1894, when scientist/inventor Étienne-Jules Marey dropped it from an unspecified height in the Bois de Boulogne, filming its descent at 12 frames per second. Ultimately, this brave and likely unsuspecting specimen furthered the cause of space exploration, though it took over 50 years for NASA-backed researchers T.R. Kane and M.P. Scher to publish their findings in a paper titled "A Dynamical Explanation of the Falling Cat Phenomenon." As the Vox Darkroom episode above makes clear, Marey’s obsession was loftier than a fondness for Stupid Pet Tricks and the mischievous impulse to drop things off of tall buildings that motivated TV host David Letterman once upon a time. Marey's preoccupation with the mechanics of organic locomotion extended to horses and humans. It prompted him to invent photographic techniques that prefigured cinematography, and, more darkly, to subject other, less-catlike creatures to deadfalls from similar heights. (Children and animal rights activists, consider this your trigger warning.) The white cat survived its ordeal by arching its back mid-air, effectively splitting its body in two to harness the inertia of its body weight, much like a figure skater controlling the velocity of her spin by the position of her arms. Why waste a single one of your nine lives? Physics is your friend, especially when falling from a great height. See one of Marey's pioneering falling cat chronophotographs below.

Related Content: Thomas Edison’s Boxing Cats (1894), or Where the LOLCats All Began An Animated History of Cats: How Over 10,000 Years the Cat Went from Wild Predator to Sofa Sidekick Explosive Cats Imagined in a Strange, 16th Century Military Manual Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Join her in NYC on Monday, September 9 for another season of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday. Why a Cat Always Lands on Its Feet: How a French Scientist Used Photography to Solve the Problem in 1894 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/08/02 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |