[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, August 6th, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | Why Is Jackie Chan the King of Action Comedy? A Video Essay Masterfully Makes the Case When’s the last time you gasped, while watching a movie, at a pure bit of physical comedy? Of a clever move, over a stunt that left you breathless, because you knew that no way was computer graphics or greenscreen involved? There are indeed some--that hallway fight in the first season of Daredevil, the endless apartment melee in Atomic Blonde, and, bear with me here, most of Jackass. But those are few and far between. During the Jackie Chan heyday, that gobsmacking disbelief happened every single film. We laughed, we winced, we cheered. For a moment, Jackie Chan was the king of action comedy. Personally, I can’t believe we *haven’t* talked about this Tony Zhou YouTube essay, because I have shown it nearly every semester in my film production class. Part of me wants to turn the young’uns on to Jackie Chan (the HK films, not the Rush Hour series), and another part hopes that these future directors will go on to correct what Hollywood gets so so wrong these days. Chan was compared early on to the giants of silent cinema like Buster Keaton, but as a young cinephile I couldn’t see past the obvious homages in films like Project A, which famously had Chan hanging off a clock tower like Harold Lloyd. It was only later that the true comparison became apparent, and Zhou lays it out for us in one of his best essays. His main points are thus: 1) Chan starts at a disadvantage and must fight his way back to the top, which links him with Chaplin and Keaton, but not like action heroes at the time like Willis and Schwarzenegger, who come fully formed. 2) Chan uses any prop to fight, not just the usual guns and swords. 3) He fights in clearly lighted scenes, with costume design to make him stand out. And here’s the main directoral point: Jackie Chan and his group of stuntmen can actually fight, and fight well. So the camera does not need to move a lot and the totality of the human body in space can be appreciated. This could only happen in a filmmaking scene like Hong Kong where productions took time and spent money to get absolutely perfect takes. Hollywood, on the other hand, does not hire actors who can fight or act physical--instead they film and edit around the actors’ lack of skill. When we applaud a clever stunt in a Jackie Chan film, 50 or more imperfect takes lay on the cutting room floor. (Zhou finds some good behind-the-scenes interviews explicitly laying this idea out.) Zhou also blames Western editors for cutting too fast and cutting too much on every hit, ruining the rhythm. Most directors, editors, and stunt coordinators don’t know editing, says Chan. There’s a technique in Hong Kong editing where you show the impact twice that to an audience feels like one, strong impact. One of the final points is that these Jackie Chan films focus on the pain of the protagonist. (Which, by the way, is why Jackass succeeds as comedy as well.) But so many Hollywood films skip this bit of reality, as our heroes tend to be invincible. There is a larger social-political critique to be made about the particular lies Hollywood tells itself, and you can have at it in the comments if you wish. But for now, queue up some classic Chan--my jumping off point all those years ago was Drunken Master II--and see how the master does it. Related Content: Judd Apatow Teaches the Craft of Comedy: A New Online Course from MasterClass Buster Keaton: The Wonderful Gags of the Founding Father of Visual Comedy Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW's Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here. Why Is Jackie Chan the King of Action Comedy? A Video Essay Masterfully Makes the Case is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

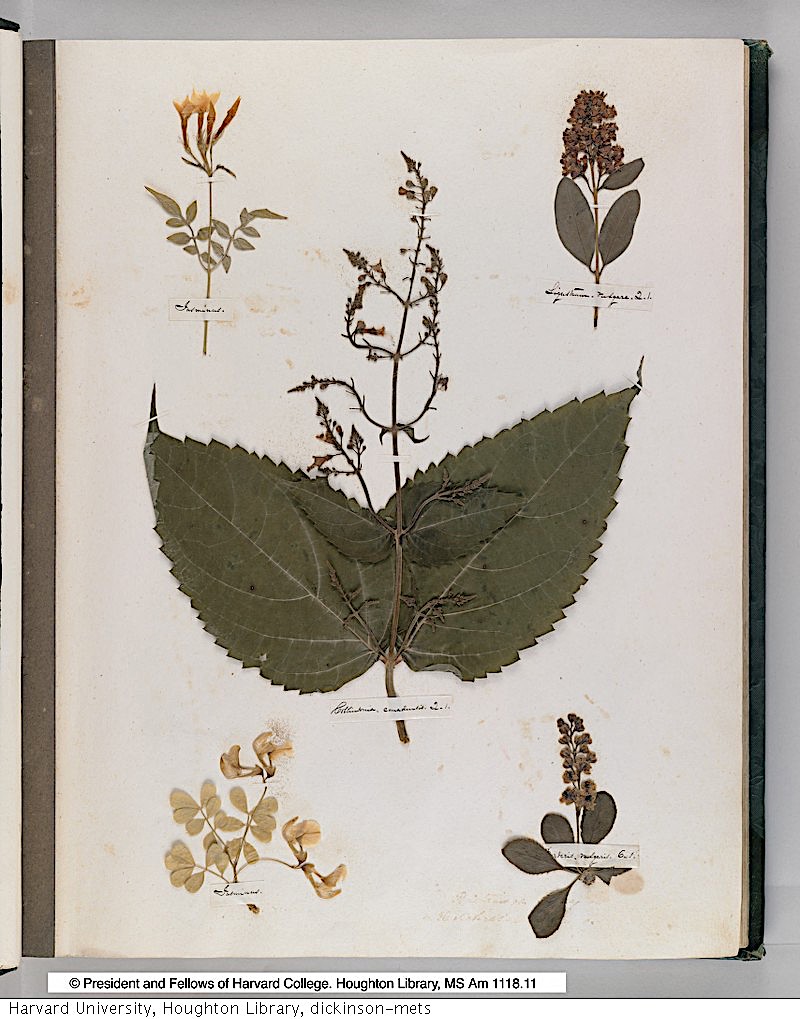

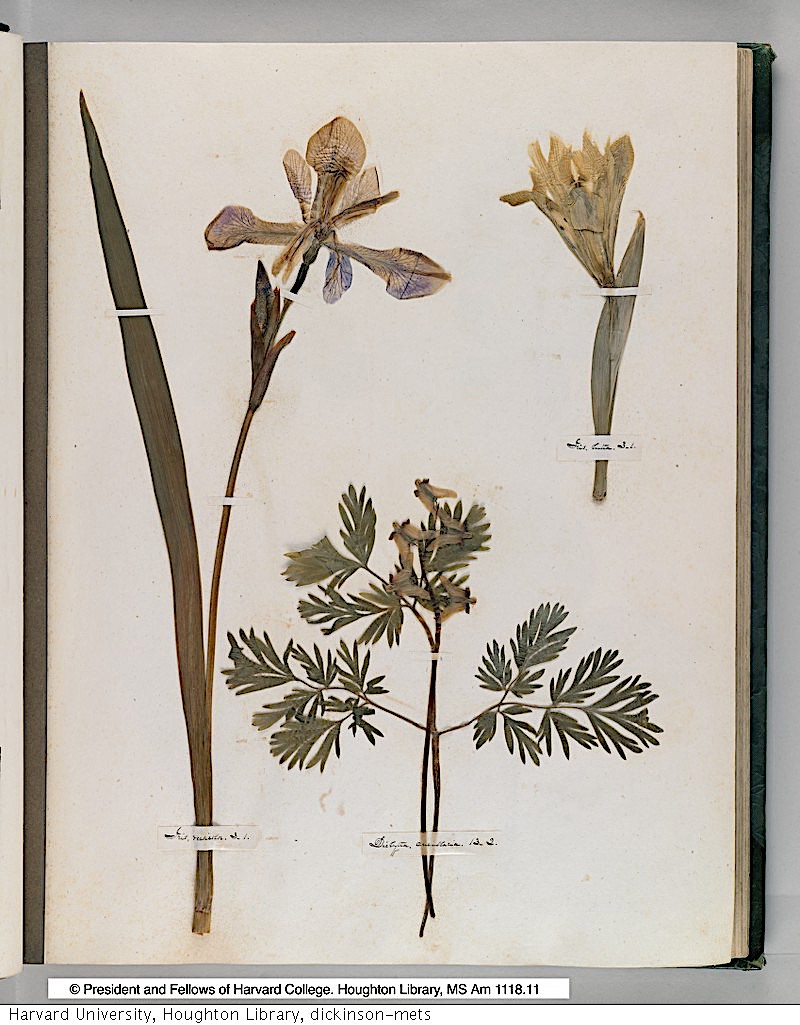

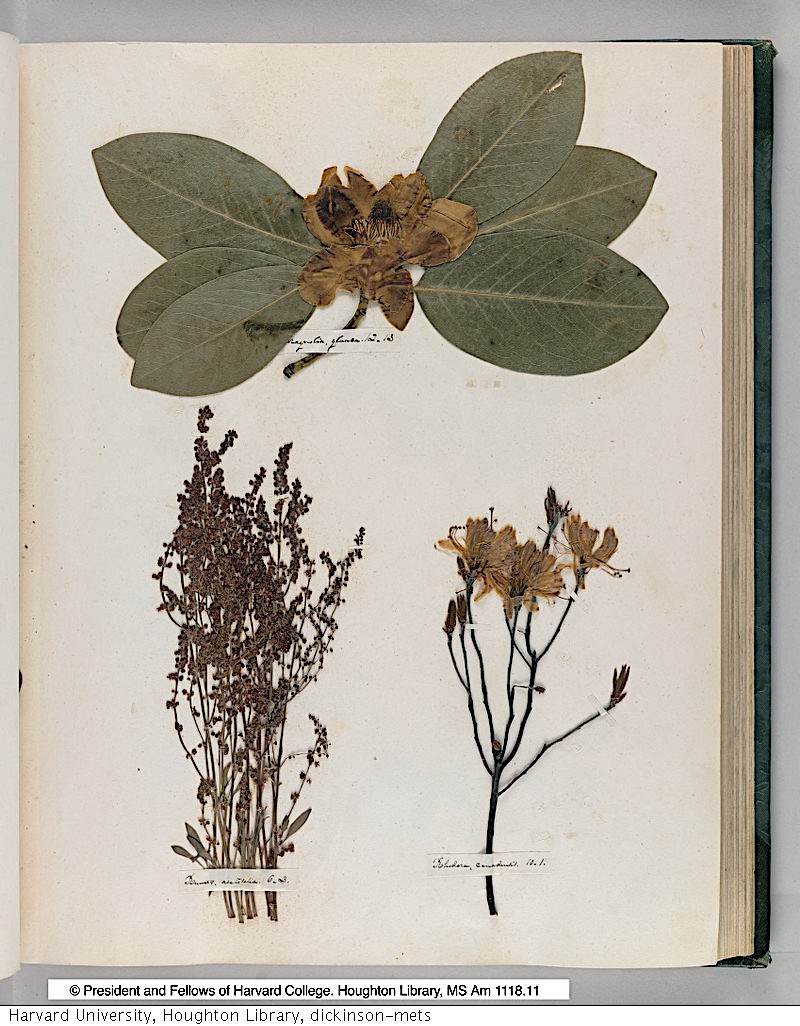

| 11:00a | Discover Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium: A Beautiful Digital Edition of the Poet’s Collection of Pressed Plants & Flowers Is Now Online

So many writers have been gardeners and have written about gardens that it might be easier to make a list of those who didn’t. But even in this crowded company, Emily Dickinson stands out. She not only attended the fragile beauty of flowers with an artist’s eye—before she’d written any of her famous verse—but she did so with the keen eye of a botanist, a field open at the time to anyone with the leisure, curiosity, and creativity to undertake it. “In an era when the scientific establishment barred and bolted its gates to women,” Brain Pickings’ Maria Popova writes, “botany allowed Victorian women to enter science through the permissible backdoor of art.” In Dickinson’s case, this involved the pressing of plants and flowers in an herbarium, preserving their beauty, and in some measure, their color for over 150 years. The Harvard Gazette describes this very fragile book, made available in 2006 in a full-color digital facsimile on the Harvard Library site:

The book is thought to have been finished by the time she was 14 years old. Long part of Harvard’s Houghton Library collection, it has also long been treated as too fragile for anyone to view. The only access has come in the form of grainy, black and white photographs. For the past few years, however, scholars and lovers of Dickinson’s work have been able to see the herbarium in these stunning reproductions.

The pages are so formally composed they look like paintings from a distance. Though mostly unknown as a poet in her life, Dickinson was locally renowned in Amherst as a gardener and “expert plant identifier,” notes Sara C. Ditsworth. The herbarium may or may not offer a window of insight into Dickinson’s literary mind. Houghton Library curator Leslie A. Morris, who wrote the forward to the facsimile edition, seems skeptical. “I think that you could read a lot into the herbarium if you wanted to,” she says, “but you have no way of knowing.” And yet we do. It may be impossible to separate Dickinson the gardener and botanist from Dickinson the poet and writer. As Ditsworth points out, “according to Judith Farr, author of The Gardens of Emily Dickinson, one-third of Dickinson’s poems and half of her letters mention flowers. She refers to plants almost 600 times,” including 350 references to flowers. Both her herbarium and her poetry can be situated within the 19th century “language of flowers,” a sentimental genre that Dickinson made her own, with her elliptical entwining of passion and secrecy.

The first two specimens in Dickinson’s herbarium are the jasmine and the privet: “You have jasmine for poetry and passion” in the language of flowers, Morris points out, “and privet,” a hedge plant, “for privacy.” There is no need to see this arrangement as a prediction of the future from the teenage botanist Dickinson. Did she plan from adolescence to become a recluse poet in later life? Perhaps not. But we can certainly “read into” the language of her herbarium some of the same great themes that recur over and over in her work, carried across by images of plants and flowers. See Dickinson’s complete herbarium at Harvard Library’s digital collections here, or purchase a (very expensive) facsimile edition of the book here. Related Content: The Online Emily Dickinson Archive Makes Thousands of the Poet’s Manuscripts Freely Available How Emily Dickinson Writes A Poem: A Short Video Introduction Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Discover Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium: A Beautiful Digital Edition of the Poet’s Collection of Pressed Plants & Flowers Is Now Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | What the First Movies Really Looked Like: Discover the IMAX Films of the 1890s Cinematic legend has it that, back in the early days of motion pictures, audiences would see a train coming toward them on the screen and dive out of the way in a panic. "There turns out to be very little confirmation of that in the actual newspaper reports of the time," says critic and Museum of Modern Art film curator Dave Kehr in the video above, "but you can still sense the excitement in seeing these gigantic, incredibly sharp, lifelike images being projected." But aren't they only sharp and lifelike by the standards of the late-19th century dawn of cinema, an era we filmgoers of the 21st century, now used to 4K digital projection, imagine as one of unrelieved blurriness, graininess, and herky-jerkiness? By no means. The footage showcased in this video, a MoMA production on "the IMAX of the 1890s," was shot on 68-millimeter film, a greater size and thus a higher definition than the 35-millimeter prints most of us have watched in theaters for most of our lives. Only the most ambitious filmmakers, like Paul Thomas Anderson making The Master, have used such large-format films in recent years, but 120 years ago an outfit like the Biograph Company could, in Kehr's words, "send camera crews around the world, as the Lumière Company had," and what those crews captured would end up in movie theaters: "Suddenly the world was coming to you in ways that people just could not have imagined. That you could go to Europe, that you could meet the crowned heads, that you could go to see elephants in India..." Thanks to the efforts of film archivists and preservationists, a few of whom appear in this video to show and explain just what degradation befalls these cinematic time capsules without the kind of work they do, much of this footage still looks and feels remarkably lifelike. "It's worth returning to these images to remind us that movies used to be analog," Kehr says. "They saw things in front of the camera in a one-on-one relationship. This was the world. It was an image you could trust. It was an image of physical substance, of reality. Nowadays we tend not to trust images, because we know how easily manipulated they are." We've gained an unfathomable amount of imagery, in terms of both quantity and quality, in our digital age. But as the sheer "ontological impact" of these old 68-millimeter clips reminds us, even when felt in streaming-video reproduction, our images have lost something as well. via Aeon Related Contents: The Art of Creating Special Effects in Silent Movies: Ingenuity Before the Age of CGI Enjoy the Greatest Silent Films Ever Made in Our Collection of 101 Free Silent Films Online Hollywood, Epic Documentary Chronicles the Early History of Cinema The History of the Movie Camera in Four Minutes: From the Lumiere Brothers to Google Glass Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. What the First Movies Really Looked Like: Discover the IMAX Films of the 1890s is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:53p | Hear Toni Morrison (RIP) Present Her Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech on the Radical Power of Language (1993) Note: We woke this morning to the news that Toni Morrison, the Nobel Prize-winning author, has died at age 88. We will pay proper tribute to her in upcoming posts. Below find a favorite from our archive, a look inside her poetic 1993 Nobel Prize acceptance speech. Since her first novel, 1970’s The Bluest Eye, Toni Morrison has dazzled readers with her commanding language—colloquial, magical, magisterial, even fanciful at times, but held firm to the earth by a commitment to history and an unsparing exploration of racism, sexual abuse, and violence. Reading Morrison can be an exhilarating experience, and a harrowing one. We never know where she is going to take us. But the journey for Morrison has never been one of escapism or art for art’s sake. In a 1981 interview, she once said, “the books I wanted to write could not be only, even merely, literary or I would defeat my purposes, defeat my audience.” As she put it then, “my work bears witness and suggests who the outlaws were, who survived under what circumstances and why.” She has sustained such a weighty mission not only with a love of language, but also with a critical understanding of its power—to seduce, to manipulate, confound, wound, twist, and kill. Which brings us to the recorded speech above, delivered in 1993 at her acceptance of the Nobel Prize for Literature. After briefly thanking the Swedish Academy and her audience, she begins, “Fiction has never been entertainment for me.” Winding her speech around a parable of “an old woman, blind but wise,” Morrison illustrates the ways in which “oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge.” Another kind of language takes flight, “surges toward knowledge, not its destruction.” In the folktale at the center of her speech, language is a bird, and the blind seer to whom it is presented gives us a choice: “I don’t know whether the bird you are holding is dead or alive, but what I do know is that it is in your hands. It is in your hands.” Language, she suggests, is in fact our only human power, and our responsibility. The consequences of its misuse we know all too well, and Morrison does not hesitate to name them. But she ends with a challenge for her audience, and for all of us, to take our own meager literary resources and put them to use in healing the damage done. You should listen to, and read, her entire speech, with its maze-like turns and folds. Near its end, the discursiveness flowers into exhortation, and—though she has said she dislikes having her work described thus—poetry. “Make up a story,” she says, “Narrative is radical, creating us at the very moment it is being created.”

Would you like to support the mission of Open Culture? Please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. Also consider following Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and sharing intelligent media with your friends. Or sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. Related Content: Toni Morrison Dispenses Writing Wisdom in 1993 Paris Review Interview 7 Nobel Speeches by 7 Great Writers: Hemingway, Faulkner, and More Toni Morrison, Nora Ephron, and Dozens More Offer Advice in Free Creative Writing “Master Class” Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness. Hear Toni Morrison (RIP) Present Her Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech on the Radical Power of Language (1993) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/08/06 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |