[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, August 14th, 2019

- “The eSports Phenomenon” by Jason Mok

- “For Men Who Hate Talking On The Phone, Games Keep Friendships Alive” by Cecilia D’Anastasio

- “How Video Games Affect the Brain” by Hannah Nichols

- “Seven Reasons to Play Computer Games” by Ryan Anderson

- “Playing Video Games Too Much Might Be Bad for Your Mental Health” by Jesse Hicks

| Time | Event |

| 7:11a | Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #6: Why Adults Might Play Video Games

Erica Spyres, Brian Hirt, and Mark Linsenmayer are joined by Ian Maio (who worked for marketing for IGN and Turner in e-sports) for our first discussion about gaming. Do adults have any business playing video games? Should you feel guilty about your video game habits? Ian gives us the lay of the land about e-sports, comparing it to physical sports, and we discuss the changing social functions of gaming, alleged and actual gaming disorders, different types of gamers, inclusivity, and more. Whether you game a lot or not at all, you should still find something interesting here. We touch on the King of Kong documentary, Grand Theft Auto, Overwatch, The Last of Us, Borderlands, Super Mario, Cuphead, NY Times Electronic Crossword Puzzle, and more. Be sure to watch the Black Mirror episode, “Striking Vipers.” Sources for this episode: This episode includes bonus content that you can only hear by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network. Please go check out Modern Day Philosophers at moderndayphilosophers.net and See You on the Other Side at othersidepodcast.com. Pretty Much Pop is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts or start with the first episode. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #6: Why Adults Might Play Video Games is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | Legendary Protest Songs from Woodstock: Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane, Country Joe & More Perform Protest Songs During the Music Festival That Launched 50 Years Ago This Week This year's big event to celebrate the 50-year anniversary of the most famous music festival in the world has died an ignominious death. As Variety wrote in a scathing “obituary” last month, "Woodstock 50 passed away today at the age of 7 months, following a brave and very, very long battle with cancel." Not a few people have said good riddance. What could the tribute—to take place not in Woodstock but in Baltimore—have in common with its namesake, save a small handful of the still-living original performers? The use of “Woodstock” as a brand seems cynical, but then again, we’ve also grown leery of the legend of Woodstock 1. What was it about? Classic rock stars on a farm? Stoned, naked hippies flailing in the mud? What justifies the fifty years of hype? Woodstock was about much more than druggy flower children shagging in bedraggled tents, yet this stereotype was propagated from the start. The festival “was a stridently antiwar spectacle,” online history project All About Woodstock explains. “Its message was diluted by the media. Rather than focus on the political statements made, mainstream cultural commentators talked about hippies, long hair, and nudity.” A belated wedding party, Woodstock symbolized “the merger and ambivalence of the counterculture and protest.” The marriage may be in shambles in the time of Woodstock 50 but it held on for several decades. Woodstock “was the ‘coming out’ party of the rock ‘n’ roll generation,” writes NPR. Folk singer Richie Havens, the festival’s first performer, remembers it as “the beginning of the world, as far as I was concerned.” Booked for a 20-minute set, Havens ended up playing for much longer when Santana couldn’t be found, ad-libbing “Freedom (Motherless Child)” as his closer. “The word ‘freedom came out of my mouth because this was our real particular freedom,” he says in an interview with NPR’s Tony Cox. “We’d finally made it to above ground.” A few months later, in December, the decade closed on a much darker note, symbolized by the Rolling Stones’ bloody Altamont Free Concert. But for three days that year, August 15-17, 1969, it seemed like music festivals might change the world. Maybe they did. Woodstock organizer Michael Lang thinks so. “I think Woodstock proved the world that it was possible for people to live peacefully,” he said in a 2015 interview. “It gave credence to the positions we as a young generation took on personal freedoms, ending a war we felt unjust, respect for the planet, the fight for civil rights, women’s rights, and human rights in general. The impact on society continues to this day.” The festival was also, of course, a massively star-studded event filled with career highlight performances like Hendrix’s radical, blistering “Star-Spangled Banner.” Not every act showed up to make a statement. The Who were pretty sour about the gig, Lang remembers. “They were not part of the ‘hippie’ thing and Pete Townsend had to be talked into taking the date.” But those who came to make a statement weren’t shy about it. Jefferson Airplane called for volunteers for the revolution in their anti-war anthem “Volunteers.” Country Joe and the Fish ended the second set on Saturday with their satirical “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag,” an explicitly anti-Vietnam War song that asked, “what are we fighting for”? Joan Baez, six months pregnant at the time, sang traditional folk songs, Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released,” and Gram Parson’s “Hickory Wind.” Her closer, spiritual “We Shall Overcome,” bridged the music of the Civil Rights movement with that of the anti-war movement, proclaiming in her glorious soprano, “We shall live in peace someday.” The moment, fifty years ago this week, can never be recreated, no matter how much money organizers throw at Woodstock retreads. But we don’t need millions to remember what the original Woodstock stood for. Sex, drugs, and mud got all the press, but the festival’s intentions were to protest war overseas and hatred and murder at home with three days of peace and music—a vision, as Havens extemporaneously sang out, of another kind of freedom. The original festival, "essentially a mass movement promoting peace," gets yet another look in a new American Experience documentary, Woodstock: Peace, Love and Music, which premiered last Tuesday on PBS. (Stream it free here.) With "never-before-seen footage" and testimonials from "those who experienced it firsthand," the film documents the event's highs and lows, including the many "near disasters" that "put the ideals of the counterculture to the test." Also see the New York Times article, "How to Relive Woodstock From the Comfort of Your Couch," which features "six movies, 12 album collections, two songs and 17 books that will take willing travelers back to August 1969." This includes, of course, Michael Wadleigh's iconic documentary, Woodstock: 3 Days of Peace and Music. Related Content: Jimi Hendrix Live at Woodstock: Historic Concert Captured on Film David Crosby & Graham Nash at Occupy Wall Street; Echoes of Woodstock Wattstax Documents the “Black Woodstock” Concert Held 7 Years After the Watts Riots (1973) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness. Legendary Protest Songs from Woodstock: Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane, Country Joe & More Perform Protest Songs During the Music Festival That Launched 50 Years Ago This Week is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

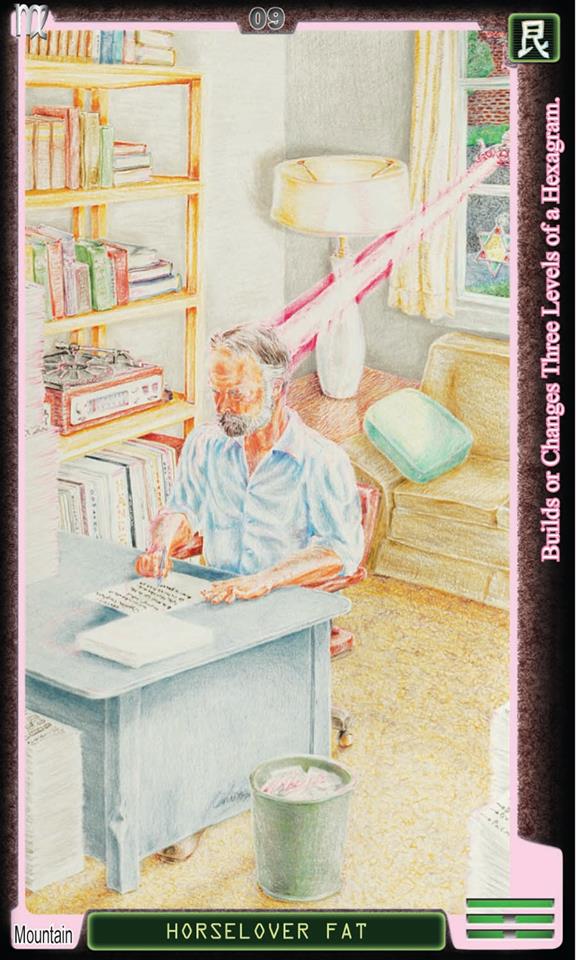

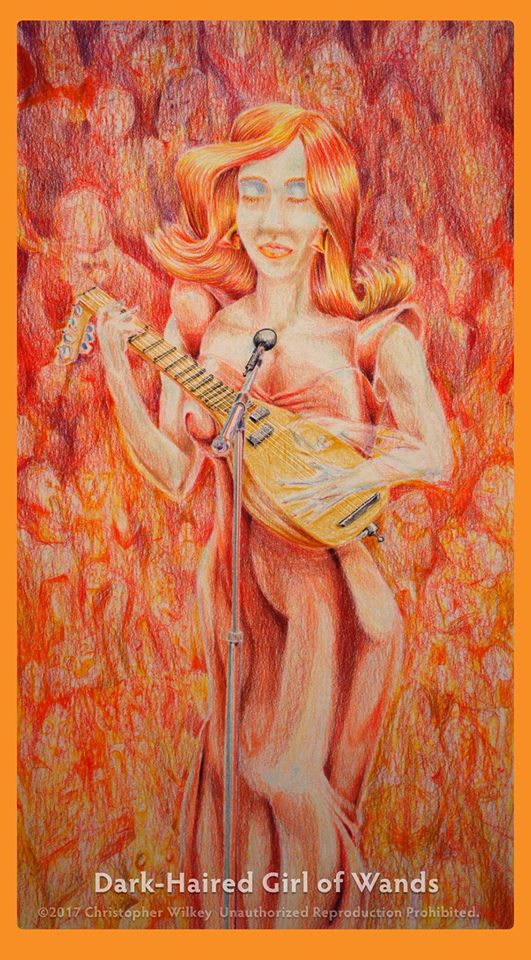

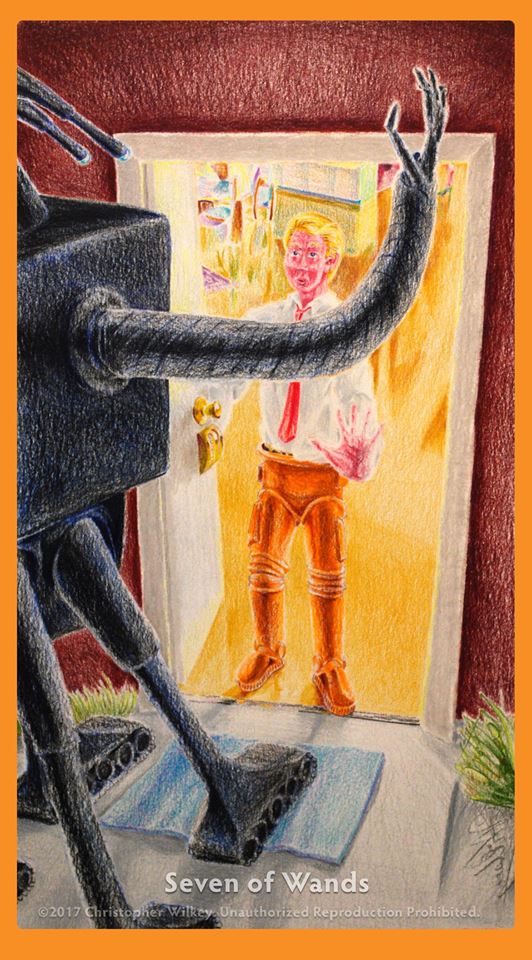

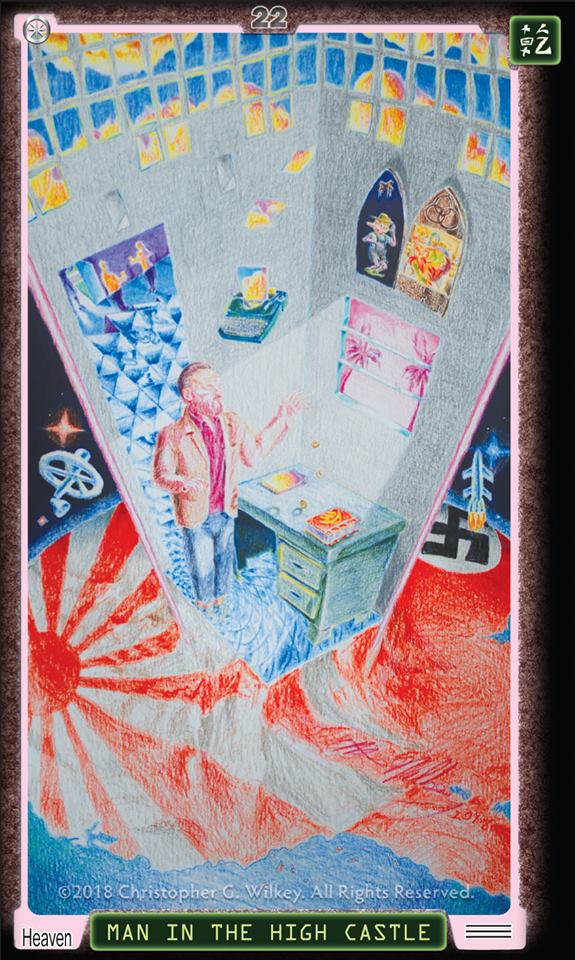

| 4:50p | Philip K. Dick Tarot Cards: A Tarot Deck Modeled After the Visionary Sci-Fi Writer’s Inner World

What does Philip K. Dick have in common with Jorge Luis Borges, Hermann Hesse, and John Cage? Fans of all three twentieth-century visionaries will have much to say on the matter of what deep resonances exist between their bodies of work and the worldviews that produced them. But they can't overlook the fact that Dick, Borges, Hesse, and Cage all, at one time or another, enthusiastically consulted the ancient Chinese divination text known as the I Ching. Also known as The Book of Changes, it became a must-have countercultural volume in the 1960s, and the words of guidance it provided, in all their openness to interpretation, surely influenced no small number of decisions made in that era.

What the I Ching had to say certainly influenced the decisions of Philip K. Dick, in life as well as in writing. Not only did he use the book to write The Man in the High Castle, his 1962 novel portraying a world in which the Axis powers won World War II, he also included it as a plot element in the story itself. And speaking of alternate histories, we might ask: could Dick have written The Man in the High Castle without the I Ching? Or could he have written it using another divination tool, perhaps one from the West rather than the East? What would the novel have looked like if written while harnessing the perceptive power of tarot, the 15th-century European card game whose decks also have a long history as windows onto human destiny?

Recently the world of tarot, the world of the I Ching, and the world of Philip K. Dick collided, resulting in The Fool's Journey of Philip K. Dick, a tarot deck published by Wide Books. "PKD scholar Ted Hand and tarot artist Christopher Wilkey have brought together a new vision of tarot and the great works of Philip K. Dick," says Wide Books' site. "Ideal for advanced students of tarot as well as novices to the I Ching," the deck "takes the seeker through an initiation into the life and writings of one of the greatest writers of recent times." In addition to its 80 cards, each drawing from some element of Dick's body of work, the deck includes "four rule cards for two I Ching inspired card games and an eight-sided folding booklet about tarot as Gnostic Allegory, with beginning exercises contrasting tarot to the I Ching."

Two of the games pay tribute to particular Dick novels: A Maze of Death and its "domino-type game" that "familiarizes players with the trigrams of which I Ching hexagrams are composed," and Ubik, which has "players either hoping to avoid accumulating entropy or trying to capture all the energy you can from the deck and other players to be the last standing at the end of the game." If that sounds like a good time to you, you'll have to register your interest in ordering a copy of The Fool's Journey of Philip K. Dick on Wide Books' contact form, since the initial run has sold out. That won't come as a surprise to Dick's fans, who know the addictive power of one glimpse into his inner world, with its rich mixture of the supernatural, the scientific, the paranormal, and the paranoid. But what kind of books will they use his tarot deck to write? Related Content: Behold the Sola-Busca Tarot Deck, the Earliest Complete Set of Tarot Cards (1490) The Tarot Card Deck Designed by Salvador Dalí The Thoth Tarot Deck Designed by Famed Occultist Aleister Crowley Twin Peaks Tarot Cards Now Available as 78-Card Deck Robert Crumb Illustrates Philip K. Dick’s Infamous, Hallucinatory Meeting with God (1974) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Philip K. Dick Tarot Cards: A Tarot Deck Modeled After the Visionary Sci-Fi Writer’s Inner World is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

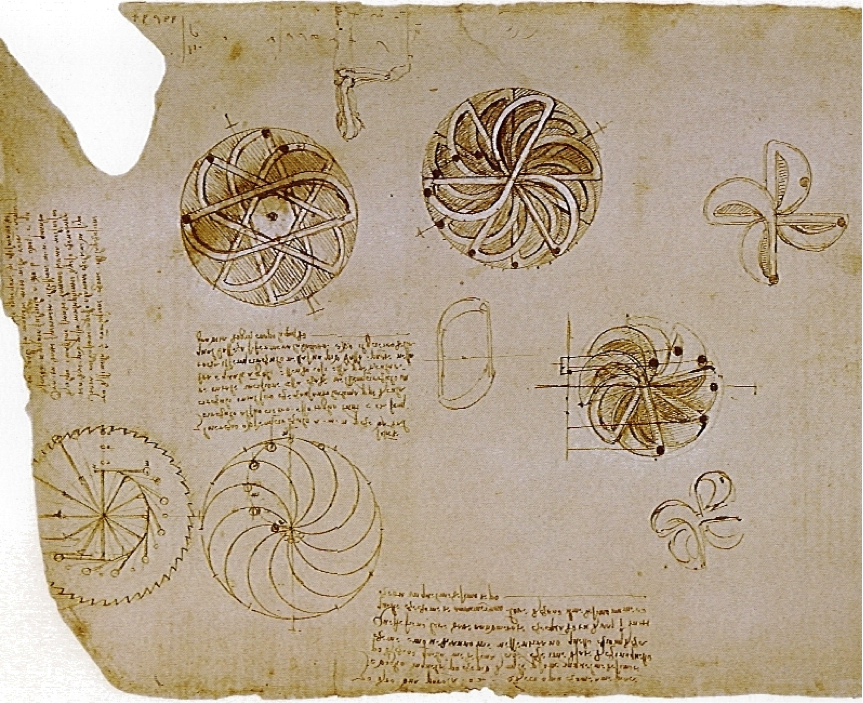

| 5:23p | Leonardo da Vinci’s Elegant Design for a Perpetual Motion Machine

Is perpetual motion possible? In theory… I have no idea…. In practice, so far at least, the answer has been a perpetual no. As Nicholas Barrial writes at Makery, “in order to succeed,” a perpetual motion machine “should be free of friction, run in a vacuum chamber and be totally silent” since “sound equates to energy loss.” Trying to satisfy these conditions in a noisy, entropic physical world may seem like a fool’s errand, akin to turning base metals to gold. Yet the hundreds of scientists and engineers who have tried have been anything but fools. The long list of contenders includes famed 12th-century Indian mathematician Bh?skara II, also-famed 17th-century Irish scientist Robert Boyle, and a certain Italian artist and inventor who needs no introduction. It will come as no surprise to learn that Leonardo da Vinci turned his hand to solving the puzzle of perpetual motion. But it seems, in doing so, he “may have been a dirty, rotten hypocrite,” Ross Pomery jokes at Real Clear Science. Surveying the many failed attempts to make a machine that ran forever, he publicly exclaimed, “Oh, ye seekers after perpetual motion, how many vain chimeras have you pursued? Go and take your place with the alchemists.” In private, however, as Michio Kaku writes in Physics of the Impossible, Leonardo “made ingenious sketches in his notebooks of self-propelling perpetual motion machines, including a centrifugal pump and a chimney jack used to turn a roasting skewer over a fire.” He also drew up plans for a wheel that would theoretically run forever. (Leonardo claimed he tried only to prove it couldn’t be done.) Inspired by a device invented by a contemporary Italian polymath named Mariano di Jacopo, known as Taccola (“the jackdaw"), the artist-engineer refined this previous attempt in his own elegant design.

Leonardo drew several variants of the wheel in his notebooks. Despite the fact that the wheel didn’t work—and that he apparently never thought it would—the design has become, Barrial notes, “THE most popular perpetual motion machine on DIY and 3D printing sites.” (One maker charmingly comments, in frustration, “Perpetual motion doesn’t seem to work, what am I doing wrong?”) The gif at the top, from the British Library, animates one of Leonardo’s many versions of unbalanced wheels. This detailed study can be found in folio 44v of the Codex Arundel, one of several collections of Leonardo’s notebooks that have been digitized and made publicly available online. In his book The Innovators Behind Leonardo, Plinio Innocenzi describes these devices, consisting of "12 half-moon-shaped adjacent channels which allow the free movement of 12 small balls as a function of the wheel’s rotation…. At one point during the rotation, an imbalance will be created whereby more balls will find themselves on one side than the other,” creating a force that continues to propel the wheel forward indefinitely. “Leonardo reprimanded that despite the fact that everything might seem to work, ‘you will find the impossibility of motion above believed.’” Leonardo also sketched and described a perpetual motion device using fluid mechanics, inventing the “self-filling flask” over two-hundred years before Robert Boyle tried to make perpetual motion with this method. This design also didn’t work. In reality, there are too many physical forces working against the dream of perpetual motion. Few of the attempts, however, have appeared in as elegant a form as Leonardo’s. See the fully scanned Codex Arundel at the British Library. Related Content: Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Leonardo da Vinci’s Elegant Design for a Perpetual Motion Machine is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/08/14 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |