[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, August 26th, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 1:51a | Stream Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, a BBC Production Featuring Derek Jacobi (Free for a Limited Time)

A nice tip from Metafilter: "BBC Radio 4 is airing Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time in 10 episodes running to about nine hours in total. With a starry cast headed by Derek Jacobi as the Narrator, the adaptation is written by U.S.-born, UK-based playwright Timberlake Wertenbaker." The entire audio collection will remain streamable for the next 28 days. Here are the individual episodes: Find more audio books in our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free. Would you like to support the mission of Open Culture? Please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. Also consider following Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and sharing intelligent media with your friends. Or sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. Related Content: The First Known Footage of Marcel Proust Discovered: Watch It Online When James Joyce & Marcel Proust Met in 1922, and Totally Bored Each Other 16-Year-Old Marcel Proust Tells His Grandfather About His Misguided Adventures at the Local Brothel Marcel Proust Fills Out a Questionnaire in 1890: The Manuscript of the ‘Proust Questionnaire’ Stream Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, a BBC Production Featuring Derek Jacobi (Free for a Limited Time) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 4:30p | Discover the Spelling Dictionary That Ludwig Wittgenstein Created for Elementary School Students

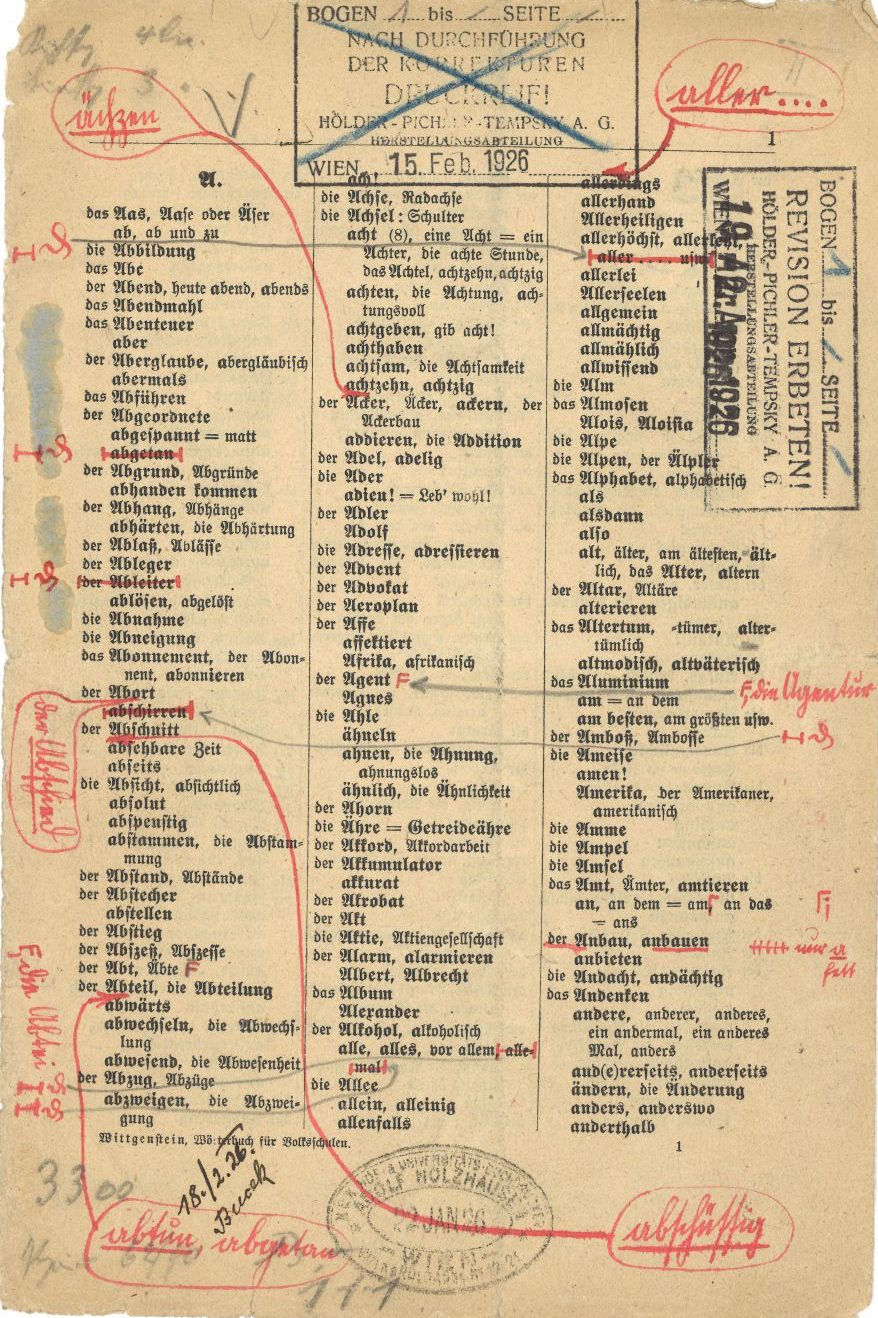

He only published two books of philosophy, and only one of them in his lifetime, but Ludwig Wittgenstein’s influence on 20th century thought is incalculable. Both of his books, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus and the posthumous Philosophical Investigations, constitute major turning points in analytic philosophy—the one inspiring the 1920s logical positivism of the Vienna Circle, the other repudiating Wittgenstein’s earlier thought and invigorating mid-century pragmatism and the Ordinary Language school. “By the 1930s,” notes Tim Rayner at Philosophy for Change, “Wittgenstein had decided” that the theory of language he had advanced in the Tractatus “was quite wrong. He devoted the rest of his life to explaining why.” This marked a dramatic shift away from the work that first made him famous, but Wittgenstein never did anything halfway. After publishing the Tractatus—partly composed while he fought in World War I—the Austrian son of a wealthy Viennese industrialist announced that he had solved all of the problems in philosophy. Nothing more needed to be said on the matter. He “retired” to try his hand at several other trades, including grade school teacher, for a period of about six years in rural villages in Austria. “By the time he decided to teach,” Spencer Robins notes at The Paris Review, “Wittgenstein was well on his way to being considered the greatest philosopher alive.” He couldn’t have cared less. “Convinced he was a moral failure, he took extreme steps to change his circumstances, divesting himself of his enormous family fortune” and choosing a profession “influenced by a romantic idea of what it would be like to work with peasants—an idea he’d gotten from reading Tolstoy.” Wittgenstein was an unsparing taskmaster, by all accounts. His brief elementary teaching career ended abruptly in 1926 when he viciously attacked a student. While his personality did not suit him to the role at all, his pedagogy was apparently very effective. Wittgenstein “engaged his students in a sort of ‘project-based learning’ that wouldn’t be out of place in the best elementary classrooms today,” writes Robins. In the last years of teaching, he worked with his students to produce what is technically his second published book—Wörterbuch für Volksschulen, a German spelling dictionary for elementary schools. One of the shocks that awaited the philosopher when he arrived in rural schools was the expense of books, and students’ inability to obtain them. “I had never realized dictionaries would be so mightily expensive,” he told educationalist Ludwig Hansel. “I think, if I live long enough, I will produce a small dictionary for elementary schools.” Often a pragmatist in life, if not always in his thought, Wittgenstein took the opportunity to turn this promise into a teachable moment, testing drafts of his dictionary in the classroom. “The improvement of spelling was astonishing,” he remarked. The dictionary, and Wittgenstein’s teaching methods in general during this period, “reveal his continued interest in the philosophy of language and its practical, everyday manifestations,” as Désirée Weber, Assistant Professor of Political Theory at the University of Wooster in Ohio, writes at the British Wittgenstein Society site. Copies of the 42-page book are extremely rare. The page above comes from a set of proof pages discovered and examined by Weber. The pages show the philosopher tailoring his reference guide to the world his students knew and the language they already spoke. “Although there is some question” which, or whether, the various editorial marks are in Wittgenstein’s own hand, “the contents of the dictionary and the corrections yield a fascinating view of the words that Wittgenstein deemed central to the forms of life and language-games in which his students were immersed.” He captured “the specificity of the rural Austrian dialect,” Weber writes at the Wittgenstein Initiative, as well as “words that pertained to cultural practices that were part of their community and with which they would have been well acquainted.” Wittgenstein elaborates his practical purpose in an introduction, showing his intent to initiate his students into their “language-using community" and into "the responsibility this carries,” Weber writes. The project also shows him engaging in the theoretical work that would occupy him for the rest of his career. Related Content: Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Short, Strange & Brutal Stint as an Elementary School Teacher In Search of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Secluded Hut in Norway: A Short Travel Film Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Discover the Spelling Dictionary That Ludwig Wittgenstein Created for Elementary School Students is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:00p | Harvard Gives Free Online Access to 40 Million Pages of U.S. Case Law: Explore 6.4 Million Cases Dating Back to 1658

There was a time—a strange time in pop culture history, I’ll grant—when legal dramas were everywhere in television, popular fiction, and film. Next to the barn-burning courtroom set pieces in A Few Good Men and A Time to Kill, for example, scenes of lawyers poring over case law with loosened ties, high heels kicked off, and martinis and scotches in hand were rendered with maximum dramatic tension, despite the fact that case law is a nigh unreadable jumble of jargon, citations, archaic diction and syntax, etc… anything but brimming with cinematic potential. Do law students and legal scholars disagree with this assessment? It’s beside the point, many might say. The centuries-old web of case law—reinforcing, contradicting, overturning, creating patterns and structures—is the very stuff the law is made of. It’s a referential tradition, and when most of the documents are in the hands of only a few people, only those people understand why the law works the way it does. The rest of us are left to wonder why the legal system is so Byzantine and incomprehensible. Real life rarely has the clarity of a satisfying courtroom drama.

Last year, The Harvard Crimson reported a seemingly revolutionary shift in that dynamic, when Harvard Law’s Caselaw Access Project “digitized more than 40 million pages of U.S. state, federal, and territorial case law documents from the Law School library,” dating back to 1658. The Crimson issued one caveat: the full database is accessible to the public, but “users are limited to five hundred full case texts per day.” Plan your intense, scotch-soaked all-nighters accordingly. Is this altruism, civic duty, a move in the right direction of freeing publicly funded research for public use? Several Harvard Law faculty have said as much. “Case law is the product of public resources poured into our court system,” writes Professor I. Glenn Cohen. “It’s great that the public will now have better access to it.” It is indeed, Professor Christopher T. Bavitz says: “If we want to ensure that people have access to justice, that means that we have to ensure that they have access to cases. The text of cases is the law.”

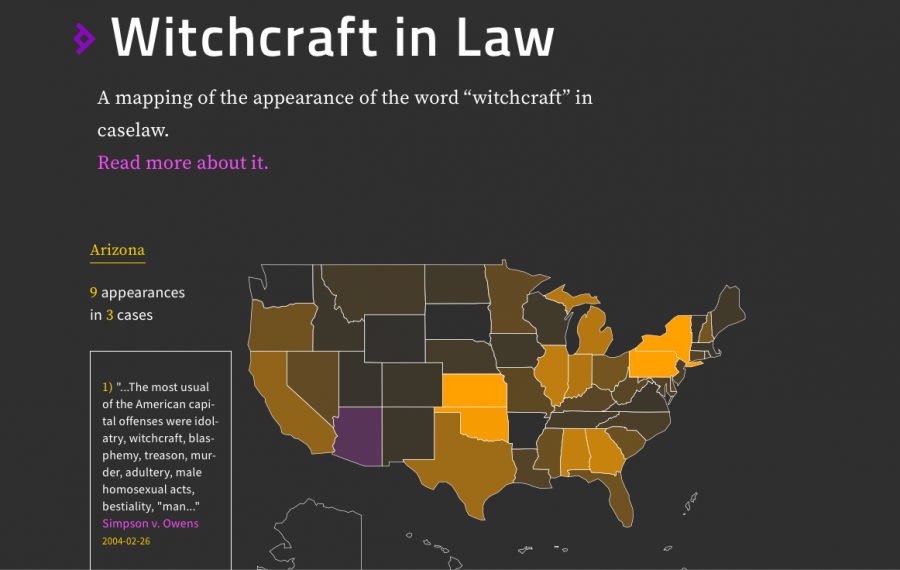

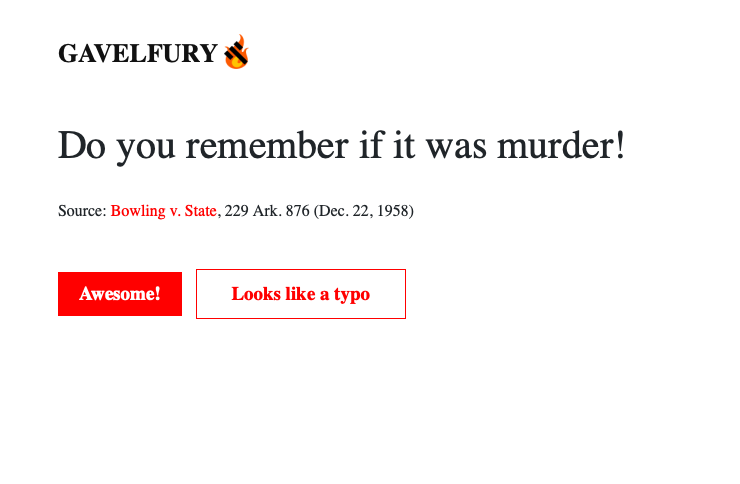

The law is not a set of abstract principles, theories, or rules, in other words, but a series of historical examples, woven together into a social narrative. Machines can analyze data from The Caselaw Access Project far faster and more efficiently than any human, giving us broader views of legal history and precedent, and greatly expanding public understanding of the system. Harvard’s Library Innovation Lab has itself already created several apps for just this purpose. There’s California Wordclouds, which shows the most-used words in California caselaw between 1852 and 2015, and Witchcraft in Caselaw, which does what it says, with an interactive map of all appearances of witchcraft in cases across the country. There’s “Fun Stuff” too, like a Caselaw Limerick Generator, a visual database that analyzes colors in case law, and “Gavelfury,” which analyzes “all instances of ‘!,’” giving us gems like “Do you remember if it was murder!” from Bowling v. State, 229 Ark. 876 (Dec. 22, 1958).

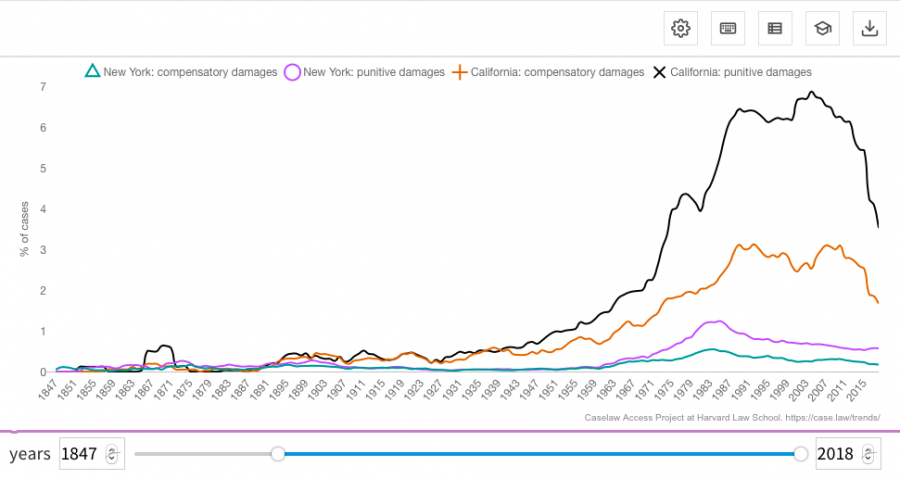

One new graphing tool, Historical Trends, announced in June, makes it easy for users to “visualize word usage in court opinions over time,” writes the Library Innovation Lab. (Examples include comparing the “frequency of ‘compensatory damages’ and ‘punitive damages’ in New York and California” and comparing “privacy” with “publicity.”) Anyone can build their own data visualization using their own search terms. (Learn how and get started here.) Case law may never be glamorous, exactly, or fun to read, but it may be far more interesting, and empowering, than we imagine. Be aware that the Caselaw Access Project could still find ways to restrict or monetize access, for a short time, at least. “The project was funded partly through a partnership with Ravel, a legal analytics startup founded by two Stanford Law School students,” reports the Crimson. The company “earned ‘some commercial rights’ through March 2024 to charge for greater access to files.” The startup has issued no word on whether this will happen. In the meantime, public interest legal scholars may wish to do their own digging through this trove of caselaw to better understand the public’s right to information of all kinds. Related Content: Bound by Law?: Free Comic Book Explains How Copyright Complicates Art Positive Psychology: A Free Course from Harvard University Harvard Launches a Free Online Course to Promote Religious Tolerance & Understanding Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Harvard Gives Free Online Access to 40 Million Pages of U.S. Case Law: Explore 6.4 Million Cases Dating Back to 1658 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 7:00p | Nigerian Teenagers Are Making Slick Sci Fi Films With Their Smartphones Someone should really snap up the rights for a movie about The Critics, a collective of self-taught teenage filmmakers from northwestern Nigeria. The boys’ dedication, ambition, and no-budget inventiveness calls to mind other filmmaking fanatics, from the sequestered, homeschooled brothers of The Wolfpack to the fictional Sweding specialists of Me and Earl and the Dying Girl and Be Kind, Rewind. While smartphones and free editing apps have definitely made it easier for aspiring filmmakers to bring their fantasies to fruition, it's worth noting that The Critics saved for a month to buy the green fabric for their chroma key effects. Their productions are also plagued with the internet and power outages that are a frequent occurrence in their home base of Kaduna, slowing everything from the rendering process to the Youtube visual effects tutorials that have advanced their craft. To date they’ve filmed 20 shorts on a smart phone with a smashed screen, mounted to a broken microphone stand that's found new life as a homemade tripod. Their simple set up will be coming in for an upgrade, however, now that Nollywood director Kemi Adetiba has brought their efforts to the attention of a much wider audience, who donated $5,800 in a fundraising campaign. It’s easy to imagine the young male demographic flocking to a feature-length, big-budget expansion of Z: The Beginning. It's possible even the art house crowd could be lured to a summer blockbuster whose setting is Nigeria, thirty years into the future, a novelty for those of us unversed in Nollywood's prodigious output. The post-apocalyptic short, above, took the crew 7 months to film and edit. The stars also inhabited a number of offscreen roles: stunt coordinator, gaffer, prop master, composer, continuity… What’s next? Earlier this month, Africa News revealed that the boys are busy with a new film whose plot they aren’t at liberty to reveal. We're guessing a sequel, to go by a not so subtle hint following Z's final credits and a moving dedication to “the ones we’ve lost.” “Horror, comedy, sci-fi, action, we do all,” The Critics’ proclaim on their Youtube channel, carefully categorizing their work as “films not skits.” (Their films’ length has thus far been dictated by the unpredictability of their wifi situation—Chase, below, is five minutes long and took two days to render. “One of the targets we aim for in the years to come is to make the biggest film in Nigeria and probably beyond,” Godwin Josiah, Z’s 19-year-old writer-director told Channels Television, Lagos' 24-hour news channel:

Watch The Critics’ films and making-ofs on their Youtube channel. Support their work with a pledge to their recently launched Patreon. Related Content: The Strange and Wonderful Movie Posters from Ghana: The Matrix, Alien & More High School Kids Stage Alien: The Play and You Can Now Watch It Online Director Robert Rodriguez Teaches The Basics of Filmmaking in Under 10 Minutes Hear Kevin Smith’s Three Tips For Aspiring Filmmakers (NSFW) Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Join her in NYC on Monday, September 9 for another season of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday. Nigerian Teenagers Are Making Slick Sci Fi Films With Their Smartphones is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/08/26 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |