[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, September 16th, 2019

| Time | Event |

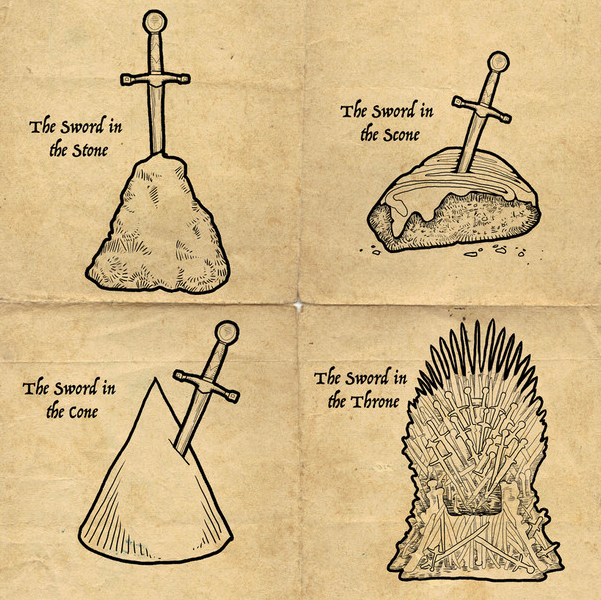

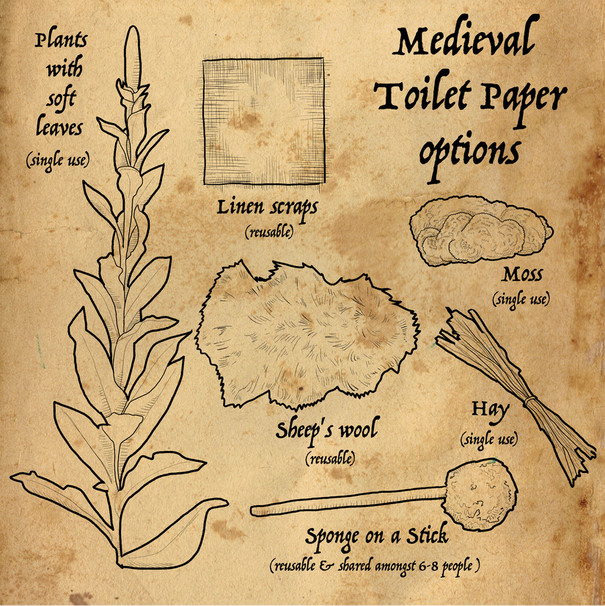

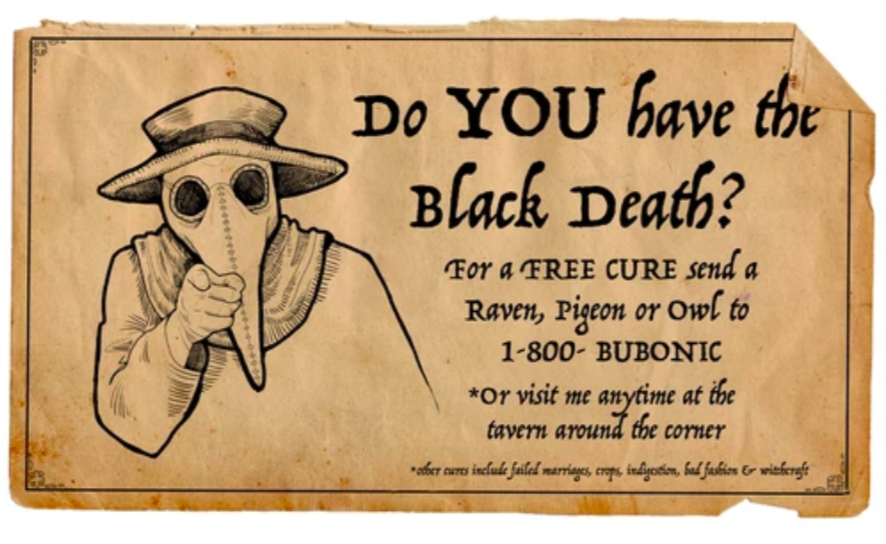

| 7:52a | Imagined Medieval Comics Illuminate the Absurdities of Modern Life

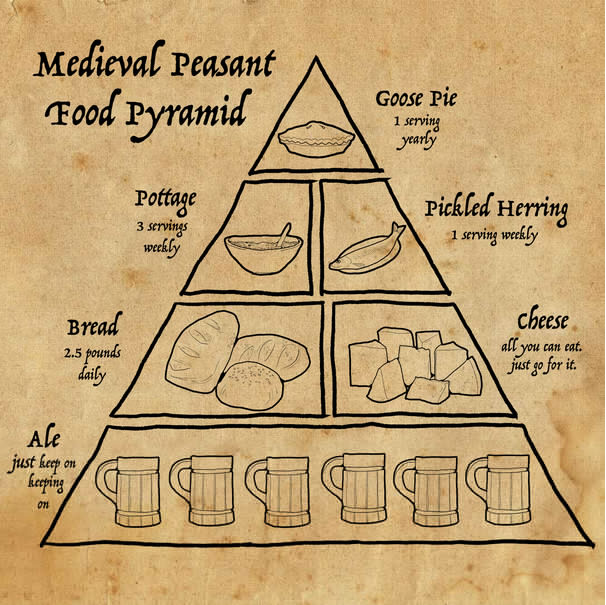

In 2005, the U.S. Department of Agriculture revised its famous food pyramid, jettisoning the familiar hierarchical graphic in favor of vertical rainbow stripes representing the various nutritional groups. A stick figure bounded up a staircase built into one side, to reinforce the idea of adding regular physical activity to all those whole grains and veggies. The dietary information it promoted was an improvement on the original, but nutritional scientists were skeptical that the public would be able to parse the confusing graphic, and by and large this proved to be the case. Artist Tyler Gunther, however, was inspired:

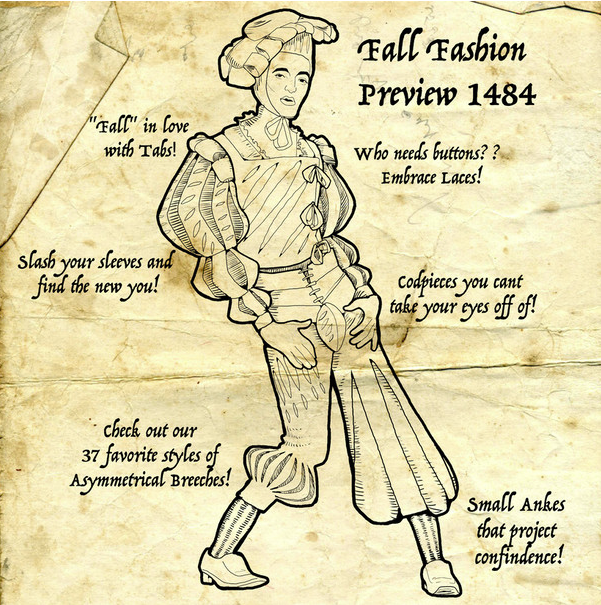

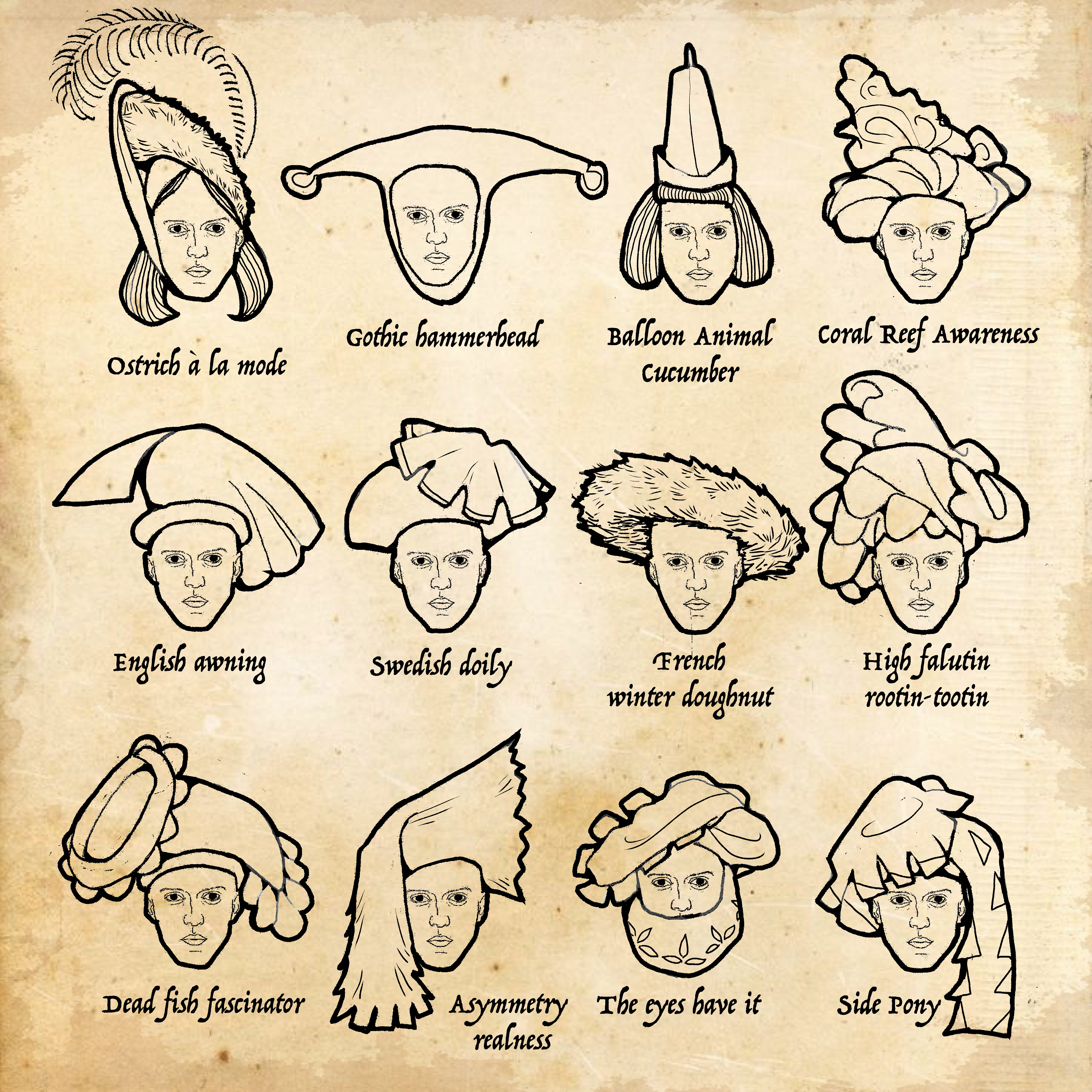

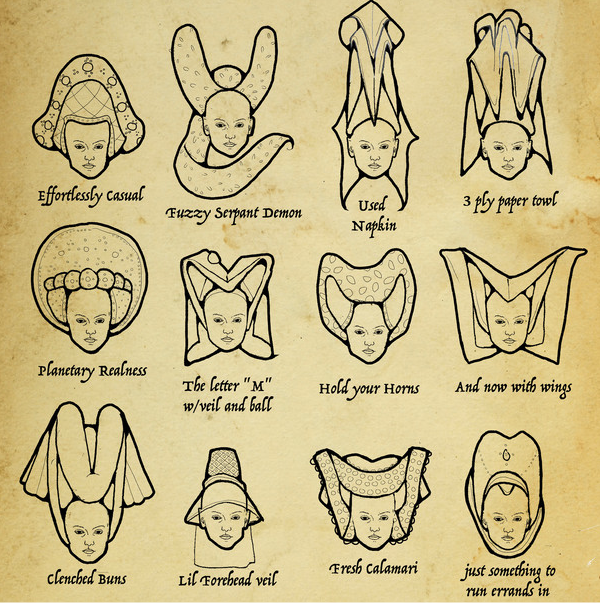

In other words, you’d better dig into that annual goose pie, kids, while you’ve still got 6 glasses of ale to wash it down. The imagined overlap between the modern and the medieval is a fertile vein for Gunter, whose MFA in Costume Design is often put to good use in his hilarious historical comics:

Kathryn Warner’s Edward II blog has proved a helpful resource, as has Anne H. van Buren’s book Illuminating Fashion: Dress in the Art of Medieval France and the Netherlands.

The Brooklyn-based, Arkansas-born artist also makes periodic pilgrimages to the Cloisters, where the Metropolitan Museum houses a vast number illuminated manuscripts, panel paintings, altar pieces, and the famed Unicorn Tapestries:

Gunther’s drawings and comics are created (and aged) on that most modern of conveniences—the iPad. The British monarchy and the First Ladies are also sources of fascination, but the middle ages are his primary passion, to the point where he recently costumed himself as a page to tell the story of Piers Gaveston, 1st Earl of Cornwall and Edward II’s darling, aided by a garment rack he’d retooled as a medieval pageant cart-cum-puppet theater.

See the rest of Tyler Gunther’s Medieval Comics on his website and don’t forget to surprise your favorite hygienist or oral surgeon with his Medieval Dentist print this holiday season. All images used with permission of artist Tyler Gunther Related Content: How to Make a Medieval Manuscript: An Introduction in 7 Videos Medieval Monks Complained About Constant Distractions: Learn How They Worked to Overcome Them Why Knights Fought Snails in Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Join her in NYC on Monday, October 7 when her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domaincelebrates the art of Aubrey Beardsley, with a special appearance by Tyler Gunther. Follow her @AyunHalliday. Imagined Medieval Comics Illuminate the Absurdities of Modern Life is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

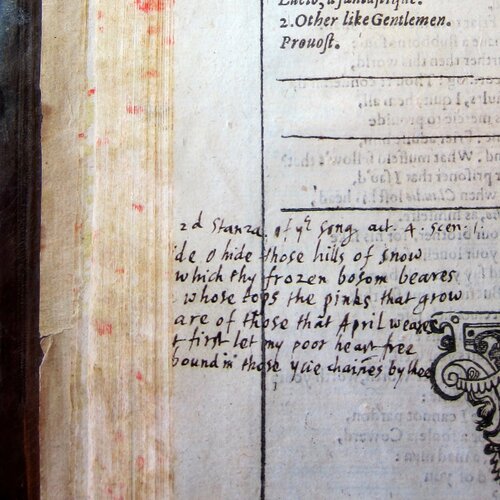

| 11:00a | John Milton’s Hand Annotated Copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio: A New Discovery by a Cambridge Scholar

Perhaps the most well-read writer of his time, English poet John Milton “knew the biblical languages, along with Homer’s Greek and Vergil’s Latin,” notes the NYPL. He likely had Dante’s Divine Comedy in mind when he wrote Paradise Lost. His own Protestant epic, if not a theological response to the Divine Comedy, had as much literary impact on the English language as Dante’s poem did on Italian. Milton would also have as much influence on English as Shakespeare, his near contemporary, who died eight years after the Paradise Lost author was born. In some sense, Milton can be called a direct literary heir of Shakespeare, though he wrote in a different medium and idiom (almost a different language), and with a very different set of concerns. Milton’s father was a trustee of the Blackfriar’s Theatre, where Shakespeare’s company of actors, the King’s Men, began performing in 1609, the year after Milton’s birth. And Milton’s first published poem appeared anonymously in the 1632 second folio of Shakespeare’s plays under the title “An Epitaph on the admirable Dramaticke Poet, W. Shakespeare.”

Now known as “On Shakespeare,” the poem laments the sorry state of Shakespeare’s legacy—his monument a “weak witness,” his work an “unvalued book.” It may be difficult to imagine a time when Shakespeare wasn’t revered, but his reputation only began to spread beyond the theater in the early 17th century. Milton’s poem was one of the first to proclaim Shakespeare’s greatness, as a poet who should lie “in such pomp” that “kings for such a tomb would wish to die.” Now, it seems that significant further evidence of Milton’s admiration, and critical appreciation, of Shakespeare has emerged: in the form of Milton’s own, personal copy of the 1623 First Folio edition of Shakespeare's plays, with annotations in Milton’s own hand. Moreover, it seems this evidence has been sitting under scholar’s noses for decades, housed in the public Free Library of Philadelphia’s Rare Book Department, one of over 230 extant copies of the First Folio.

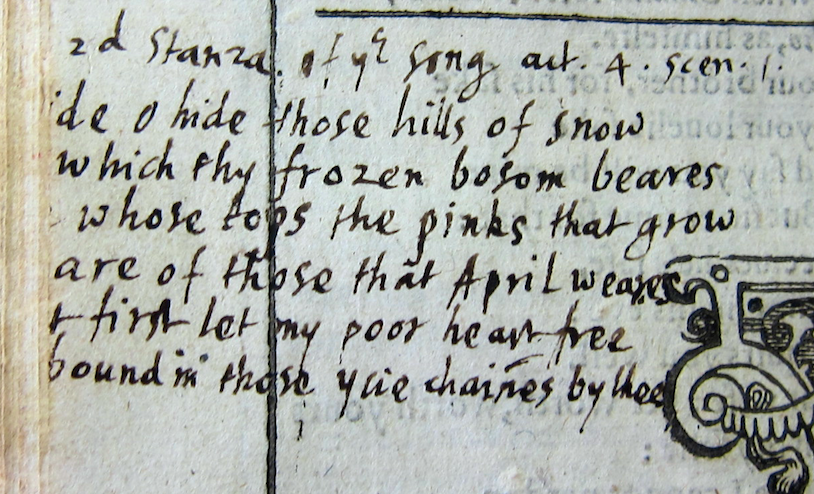

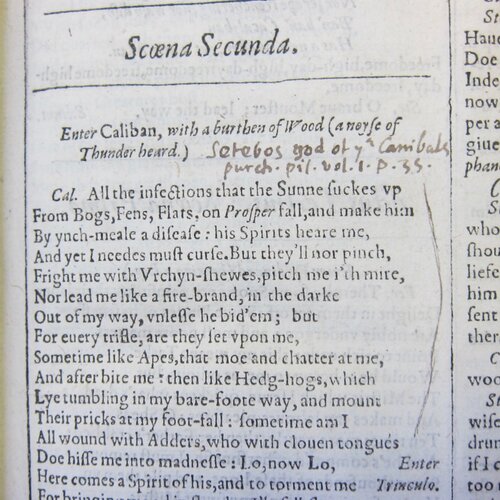

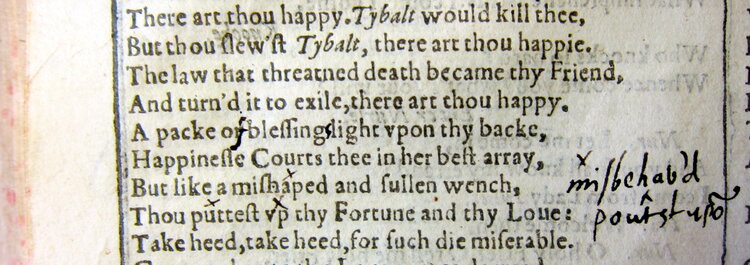

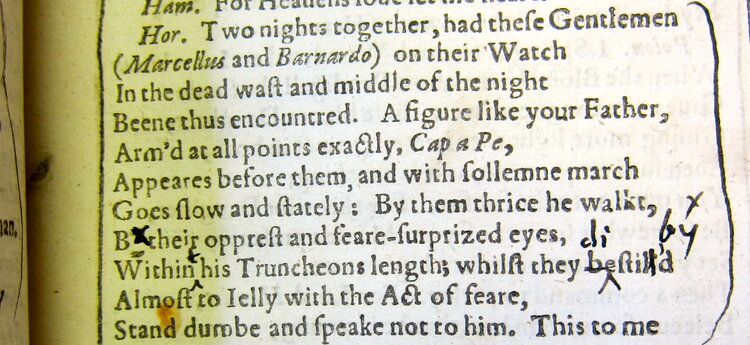

In a blog post at the Centre for Material Texts, the University of Cambridge’s Jason Scott-Warren makes his case that the annotated First Folio is Milton’s own, primarily, he writes, on the basis of paleography, or handwriting analysis. “This just looks like Milton’s hand,” he says, then walks through several comparisons with other known Milton manuscripts, such as his commonplace book and annotated Bible. There is also the copious evidence for dating the book to the time Milton would have owned it, from the many marginal references to contemporary works like Samuel Purchas’ 1625 Pilgrimes and John Fletcher’s The Bloody Brother. Milton “added marginal markings to all of the plays except for Henry VI 1-3 and Titus Andronicus,” notes Scott-Warren. His corrections—from the Quarto—emendations, and “smart cross-references” are “intelligent and assiduous.”

Anticipating blowback for his Milton theory, Scott-Warren asks, “wouldn’t his copy be bristling with cross-references, packed with smart observations and angrily censorious comments?” It would indeed, and “several distinguished Miltonists” have agreed with Scott-Warren’s analysis, many contacting him, he writes in a postscript, to say they’re “confident that this identification is correct." He adds that he has “been roundly rebuked for understating the significance of the discovery.” This kind of self-reported validation isn’t exactly peer review, but we don’t have to take his word for it. Said scholars have made their approval publicly, enthusiastically, known on Twitter. And Penn State Assistant Professor of English Claire M.L. Bourne has written a congratulatory essay on her blog. It was Bourne who spurred on Scott-Warren’s investigation with her own essay “Vide Supplementum: Early Modern Collation as Play-Reading in the First Folio,” published just months earlier this year.

Bourne was one of the first few scholars to thoroughly examine the Free Library of Philadelphia’s copy of the First Folio. But, she admits, she completely missed the Milton connection. “You can work for a decade,” she writes ruefully, “as I did, on a single book… and still be left with gaping holes in the narrative.” This new scholarship may not only have filled in the mystery of the book’s first owner and annotator; it may also show the full degree to which Milton engaged with Shakespeare, and give Milton scholars “a new and significant field of reference” for reading his work. via MetaFilter Related Content: William Blake’s Hallucinatory Illustrations of John Milton’s Paradise Lost Spenser and Milton (Free Course) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness John Milton’s Hand Annotated Copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio: A New Discovery by a Cambridge Scholar is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | How Sergio Leone Made Music an Actor in His Spaghetti Westerns, Creating a Perfect Harmony of Sound & Image Nearly everyone who's heard music has also received intense feelings from music. "We know that music activates parts of the brain that regulate emotion, that it can help us concentrate, trigger memories, make us want to dance," says Evan Puschak, better known as the Nerdwriter, in his latest video essay. "Music fits so well with the patterns of thought, it's almost as if that lyrical quality is latent in life, or reality, or both. In film, no one understood this better than Sergio Leone, the Italian director of operatic spaghetti Westerns." And though you may not have seen any spaghetti Westerns yourself — even Leone's Clint Eastwood-starring trilogy of A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly — you've surely heard their music. The fame of the spaghetti Western score owes mostly to composer Ennio Morricone, whose collaboration with Leone "is arguably the most successful in all of cinema," thanks to "the deep respect Leone had for Morricone's work, but also his general feeling for how music should function in film." Unlike most filmmakers, who then, as now, commissioned a picture's score only after they completed the shooting, and sometimes even the editing, Leone would get Morricone's music first, "then design shots around those compositions. The music, for Leone, really was a kind of script." Using scenes from Once Upon a Time in the West, Puschak shows that music was also an actor, in the sense that Leone brought it to the set so his human actors could react to it during the shoot. Often the music we hear in the background is also what the actors were hearing in the background, and what Leone used to orchestrate their actions and expressions. Puschak calls the result "a perfect harmony of sound and image," whether the visual element may be a soaring crane shot or the kind of extended close-up he favored of a human face. Among living filmmakers, the spaghetti Western-loving Quentin Tarantino has most clearly followed in Leone's footsteps, to the point that he incorporated Morricone's music in several films before commissioning an original score from the composer for his own western The Hateful Eight. He goes in no more than Leone did for the "temp score," the standard Hollywood practice of filling the soundtrack of a movie in production with existing music and then asking a composer to write replacement music that sounds like it — a major cause of all the bland film scores we hear today. To go back to Once Upon a Time in the West, or any other of Leone's Westerns, is to understand once again what role music in film can really play. Related Content: Quentin Tarantino Lists His 20 Favorite Spaghetti Westerns The Music in Quentin Tarantino’s Films: Hear a 5-Hour, 100-Song Playlist Watch the Opening of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey with the Original, Unused Score Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. How Sergio Leone Made Music an Actor in His Spaghetti Westerns, Creating a Perfect Harmony of Sound & Image is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:40p | 25 John Lennon Fans Sing His First Post-Beatles Album, Working Class Hero, Word for Word, and Note for Note

Artist Candice Breitz knows that a true fan’s connection to a beloved musical artist is a source of power, however lopsided the “relationship” may be. Favorite albums are touchstones that get us through good times and bad. They pin us to a particular place and time. There are patches when it feels like a singer we’ve never met is the only one in the world who truly knows us. Just ask your average teenager. A dime will net you dozens upon dozens of Beatles fans, but a person who knows all the words to John Lennon / Plastic Ono Band, the 1970 solo album that followed hard on the heels of the Fab Four’s break up inhabits a far more rarified strata of fandom. That person has earned the mantle of tried-and-true John fan. And 25 of those earned a spot in Breitz’s 2006 "Working Class Hero (A Portrait of John Lennon)," above, a multi-channel singalong of the aforementioned John Lennon / Plastic Ono Band. As with Breitz’s previous portraits of Bob Marley, Madonna, and Michael Jackson, the singer is the elephant in the room, the only voice absent from the choir that forms when the participants’ solo recording sessions are played simultaneously, as they are in the finished piece. Recruited by notices in papers throughout the UK, including the Liverpool Echo, the fans’ degree of devotion, as evidenced by their responses to an in-depth questionnaire, mattered far and above training, talent, or appearance:

Those who made the cut were reimbursed for travel to a recording studio at Newcastle University, and filmed wearing their own clothes, free to emote or not as they saw fit. Some may have fallen shy of the “30 years or more” requirement, and indeed, may not even have been born at the time of Lennon’s 1980 murder. Just more proof of this legend’s staying power. Their stamina is to be congratulated. It’s no easy feat to open with "Mother," a literal screamer born of Lennon’s forays into Primal Therapy. And the tenderness they bring to quieter numbers like "Love" and "Hold On" is touching indeed. It’s not hard to guess who they’re singing to. (It’s also really fun to witness them fumbling through "Hold On"’s ad-libbed “cookies,” a salute to Cookie Monster that also harkens to the childhood regression Lennon underwent as part of his Primal Therapy.) Readers, if you were given the opportunity to contribute to one of Candice Breitz’s composite celebrity portraits, who would you want to pay tribute to, living or dead? Related Content: 30 Fans Joyously Sing the Entirety of Bob Marley’s Legend Album in Unison Hear the Original, Never-Heard Demo of John Lennon’s “Imagine” Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Join her in NYC on Monday, October 7 when her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domaincelebrates the art of Aubrey Beardsley. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

25 John Lennon Fans Sing His First Post-Beatles Album, Working Class Hero, Word for Word, and Note for Note is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/09/16 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |