[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, September 24th, 2019

| Time | Event |

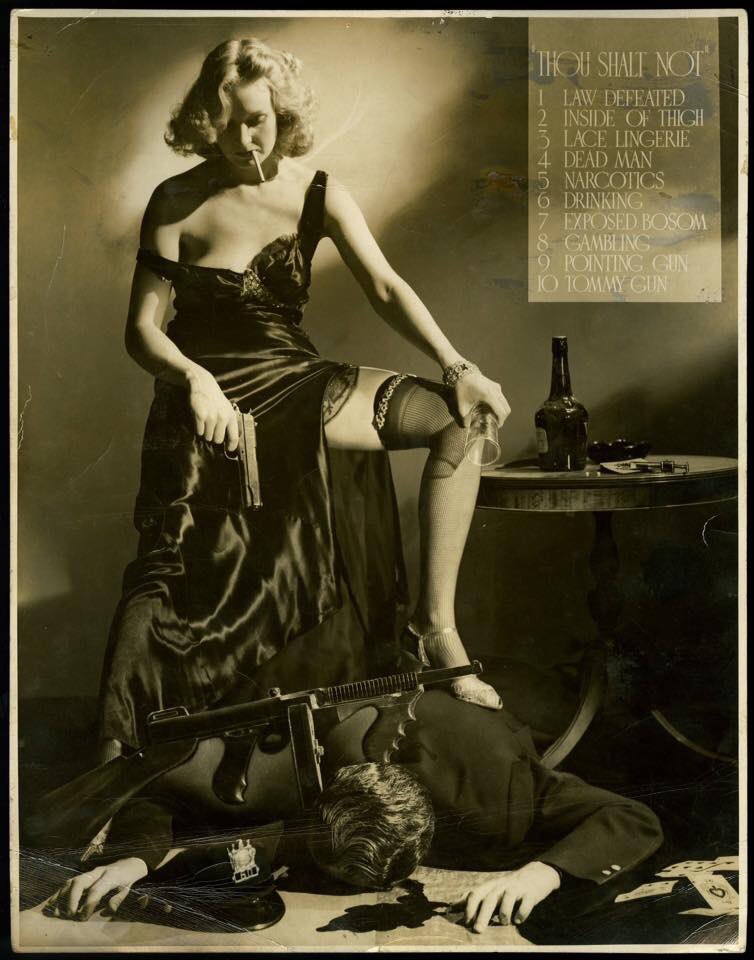

| 11:00a | “Thou Shalt Not”: A 1940 Photo Satirically Mocks Every Vice & Sin Censored by the Hays Movie Censorship Code

The history of Hollywood film before 1968 breaks down into two eras: "pre-Code" and "post-Code." The "Code" in question is the Motion Picture Production Code, better known as the "Hays Code," a reference to Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America president Will H. Hays. The organization we now know as the MPAA hired Hays in 1922, tasking the Presbyterian deacon and former chairman of the Republican National Committee and Postmaster General with "cleaning up" early Hollywood's sinful image. Eight years into Hays' presidency came the Code, a pre-emptive act of self-censorship meant to dictate the morally acceptable — and more importantly, the morally unacceptable — content in American film. "The code sets up high standards of performance for motion-picture producers," NPR's Bob Mondello quotes Hays as saying at the Code's 1930 debut. "It states the considerations which good taste and community value make necessary in this universal form of entertainment." No picture, for example, should "lower the moral standards of those who see it," and "the sympathy of the audience shall never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin." There was also "an updated, much-expanded list of 'don'ts' and 'be carefuls,' with bans on nudity, suggestive dancing and lustful kissing. The mocking of religion and the depiction of illegal drug use were prohibited, as were interracial romance, revenge plots and the showing of a crime method clearly enough that it might be imitated." Serious enforcement of the Code commenced in 1934, and it didn't take long thereafter for Hollywood filmmakers to start flouting it. "American film producers are inured by now to the Hays Office which regulates movie morals," says a Life article from 1946. Indeed, "knowing that things banned by the code will help sell tickets," those producers "have been subtly getting around the code for years." In other words, they "observe its letter and violate its spirit as much as possible." Atop the article appears an enormous photograph, taken by Paramount photographer A. L. “Whitey” Schafer, that "shows, in one fell swoop, many things producers must not do," or rather must not depict: the defeat of the law, the inside of the thigh, narcotics, drinking, an "exposed bosom," a tommy gun, and so on. For 1941's inaugural Hollywood Studios’ Still Show, "Schafer decided to create a novelty shot to satirically slap at the Production Code, the censorship standards of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Assn," writes Hollywood historian Mary Mallory. "His satirical image, entitled, “Thou Shalt Not,” displayed the top 10 faux-pas disallowed by industry censors, who approved every photographic image shot by studios before they could be distributed." When "outraged organizers pulled the image from the competition" and threatened Schaefer with a fine, he explained that "all the judges were hoarding the 18 prints submitted for the show." Few of us today would feel so titillated, let alone morally corrupted, by Schafer's image, but as filmmaker Aislinn Clarke recently demonstrated on Twitter, it may offer more pure entertainment value than ever. (via @AislinnClarke) Related Content: A Brief History of Hollywood Censorship and the Ratings System The 5 Essential Rules of Film Noir The Essential Elements of Film Noir Explained in One Grand Infographic Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. “Thou Shalt Not”: A 1940 Photo Satirically Mocks Every Vice & Sin Censored by the Hays Movie Censorship Code is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:01a | An Animated Michael Sandel Explains How Meritocracy Degrades Our Democracy Imagine if governments and institutions took their policy directives straight from George Orwell’s 1984 or Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal.” We might veer distressingly close to many a literary dystopia in these times, with duckspeak taking over all the discourse. But some lines—bans on thinking or non-procreative sex, or seriously proposing to eat babies—have not yet been crossed. When it comes, however, to meritocracy—a term that originated in a 1958 satirical dystopian novel by British sociologist Michael Young—it can seem as if the political class had taken fiction as manifesto. Young himself wrote in 2001, “much that was predicted has already come about. It is highly unlikely the prime minister has read the book, but he has caught on to the word without realizing the dangers of what he is advocating.” In Young's historical analysis, what began as an allegedly democratic impulse, a means of breaking up hereditary castes, became itself a way to solidify and entrench a ruling hierarchy. “The new class has the means at hand,” wrote Young, “and largely under its control, by which it reproduces itself.” (Wealthy people bribing their children's way into elite institutions comes to mind.) Equal opportunity for those who work hard and play by the rules doesn’t actually obtain in the real world, meritocracy's critics demonstrate—prominent among them the man who coined the term “meritocracy.” One problem, as Harvard’s Michael Sandel frames it in the short RSA animated video above, is an ancient one, characterized by a very ancient word. “Meritocratic hubris,” he says, “the tendency of winners to inhale too deeply of their success,” causes them to “forget the luck and good fortune that helped them on their way.” Accidents of birth are ignored in a hyper-individualist ideology that insists on narcissistic notions of self-made people and a just world (for them). “The smug conviction that those on the top deserve their fate” comes with its inevitable corollary—“those on the bottom deserve theirs too,” no matter the historical, political, and economic circumstances beyond their control, and no matter how hard they might work or how talented they may be. Meritocracy obviates the idea, Sandel says, that “there but for the grace of God or accidents of fortune go I,” which promoted a healthy degree of humility and an acceptance of life's contingency. Sandel sees meritocratic attitudes as corrosive to democracy, describing their effects in his upcoming book The Tyranny of Merit. Yale Law Professor Daniel Markovits, another ivy league academic and heir to Michael Young's critique, has also just released a book (The Meritocracy Trap) decrying meritocracy. He describes the system as a “trap” in which “upward mobility has become a fantasy, and the embattled middle classes are now more likely to sink into the working poor than to rise into the professional elite.” Markovitz, who holds two degrees from Yale and a doctorate from Oxford, admits at The Atlantic that most of his students “unnervingly resemble my younger self: They are, overwhelmingly, products of professional parents and high-class universities.” Once an advocate of the idea of meritocracy as a democratic force, he now argues that its promises “exclude everyone outside of a narrow elite…. Hardworking outsiders no longer enjoy genuine opportunity.” According to Michael Young, meritocracy’s tireless first critic and theorist (he adapted his satire from his 1955 dissertation), “those judged to have merit of a particular kind,” whether they truly have it or not, always had the potential, as he wrote in The Guardian, to “harden into a new social class without room in it for others.” A class that further dispossessed and disempowered those viewed as losers in the endless rounds of competition for social worth. Young died in 2002. We can only imagine what he would have made of the exponential extremes of inequality in 2019. A utopian socialist and tireless educator, he also became an MP in the House of Lords and a baron in 1978. Perhaps his new position gave him further vantage to see how “with the coming of the meritocracy, the now leaderless masses were partially disfranchised; a time has gone by, more and more of them have been disengaged, and disaffected to the extent of not even bothering to vote. They no longer have their own people to represent them.” Related Content: Michael Sandel’s Famous Harvard Course on Justice Launches as a MOOC on Tuesday Free: Listen to John Rawls’ Course on “Modern Political Philosophy” (Recorded at Harvard, 1984) Piketty’s Capital in a Nutshell Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness An Animated Michael Sandel Explains How Meritocracy Degrades Our Democracy is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | A Brief History of the Great American Road Trip I live in Asia, where no few people express an interest in traveling to my homeland, the United States of America. When I meet such people, I always give them the same advice: if you go, make sure to take a cross-country road trip. But then I would say that, at least according to the premise of the PBS Idea Channel video above, "Why Do Americans Love Road Trips?" While driving from New York to Louisville, Nashville, and then Philadelphia, host Mike Rugnetta theorizes about the connection between the road trip and the very concept of America. It begins with physical suitability, what with the U.S.' relatively low gas prices, amenable terrain, and sheer size: "America is big," Rugnetta points out. "Some might say too big." As Rugnetta drives farther, he goes deeper: for quite a long stretch of U.S. history, "progress and mobility were peas in a pod, and mobility has always been a subtext of America's favorite societal bulwark, freedom." In other words, "America's idea of its own awesomeness" — and does any word more clearly mark modern American speech? — "is very much built on metaphors having to do with movement." In the 20th century, movement came to mean cars, especially as the end of the Second World War and the beginning of the 1950s came around, at which time President Eisenhower, "inspired by the awesome system of roads he saw in Germany," authorized the construction of a national highway system, the replacement for storied but non-comprehensive interstate roads like Route 66. From then on, the United States saw an enormous surge in both car ownership, auto-industry employment, "the middle class, suburbia, fast food," and a host of other phenomena still seen as characteristically American. "To say that modern America was built both by and for the car," as Rugnetta puts it, "would not be an insane overstatement." But he also notes that the idea of the road trip itself goes back to 1880s Germany, when Bertha Benz, wife of Benz Moterwagen founder Karl Benz, took her husband's then-experimental car on a then-illegal 66-mile drive through the countryside. The first American road trip was taken in 1903 by a doctor named Horatio Jackson and, as the Rough Guides video above tells it, involved a bet, a dog, and — the whole way from San Francisco to New York — no signage at all. Rugnetta also presents a philosophical question, derived from the Sorites Paradox: at what point does a "drive" turn into a "road trip?" Does it take a certain number of miles, of gas-tank refills, of roadside attractions? A coast-to-coast drive of the kind pioneered by Jackson unquestionably qualifies as a road trip. So does the automobile journey taken by Dutchman Henny Hogenbijl in the summer of 1955, his color film of which you can see above. Beginning with footage of Amsterdam's Schiphol Airport, New World Symphony shows off the sights Hogenbijl saw while driving from New York to Los Angeles, with places like Niagara Falls, Chicago, Mount Rushmore, Yellowstone National Park, and Salt Lake City as the stops in between — or the places, to use the phrase Rugnetta credits with great importance in American myth, Hogenbijl was just "passin' through." Not long ago, a modern-day Hogenbijl made that great American road trip with the destinations reversed. Like Hogenbijl, he filmed it; unlike Hogenbijl, he filmed not the stops but the driving itself, and every single minute it took him to get across the United States at that. Lucky for the busy viewer, the video compresses this eight days of footage into a mere seven hours, adding an indicator of the state being passed through in the lower-left corner of the frame. Even sped up, the viewing experience underscores a point I try to make to all the hopeful road-trippers I meet on this side of the world: you must drive across America not just to experience how interesting the country is, but at the same time how boring it is. Allow me one use that most characteristically American locution when I say that both America's interestingness and its boringness, as well as its many other qualities best seen on the road, inspire awe — that is, they're awesome. Related Content: Why Route 66 Became America’s Most Famous Road If You Drive Down a Stretch of Route 66, the Road Will Play “America the Beautiful” 12 Classic Literary Road Trips in One Handy Interactive Map Four Interactive Maps Immortalize the Road Trips That Inspired Jack Kerouac’s On the Road Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. A Brief History of the Great American Road Trip is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/09/24 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |