[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, September 26th, 2019

| Time | Event |

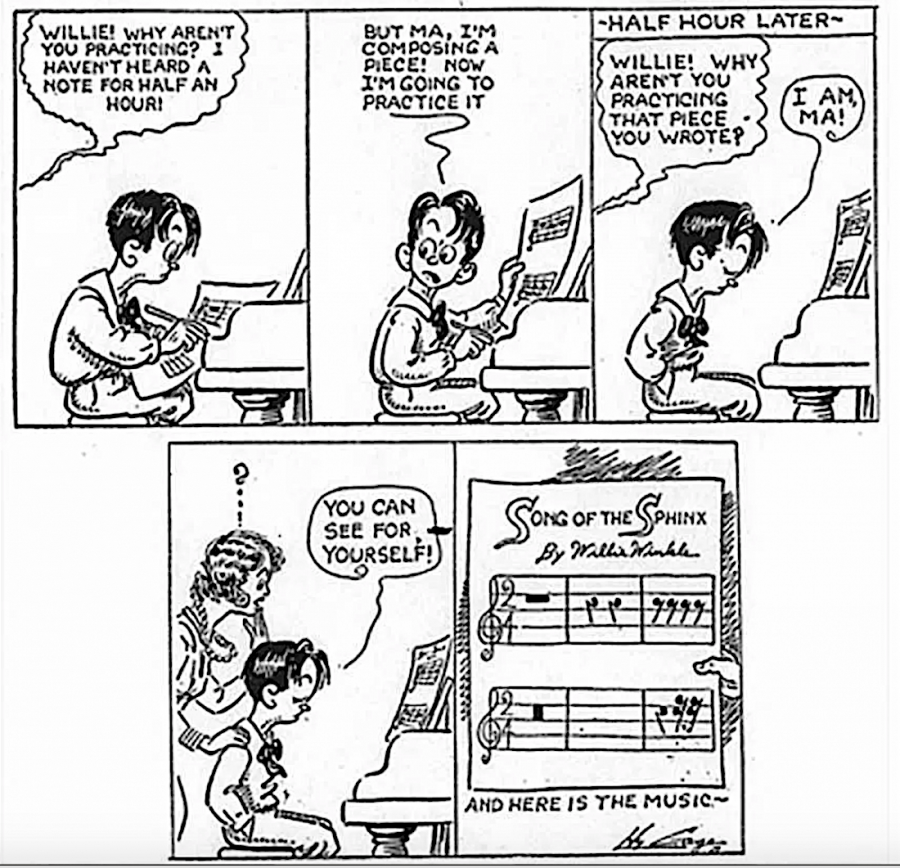

| 8:00a | 20 Years Before John Cage’s 4’33”, a Man Named Hy Cage Created a Cartoon about a Silent Piano Composition (1932)

Quite a find by Futility Closet:

Need any background on Cage's 4'33"? Explore the posts in the Relateds below. Related Content: John Cage’s Silent, Avant-Garde Piece 4’33” Gets Covered by a Death Metal Band John Cage Performs His Avant-Garde Piano Piece 4’33” … in 1’22” (Harvard Square, 1973) The Curious Score for John Cage’s “Silent” Zen Composition 4’33” 20 Years Before John Cage’s 4’33”, a Man Named Hy Cage Created a Cartoon about a Silent Piano Composition (1932) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | Human All Too Human: A Roman Woman Visits the Great Pyramid in 120 AD, and Carves a Poem in Memory of Her Deceased Brother

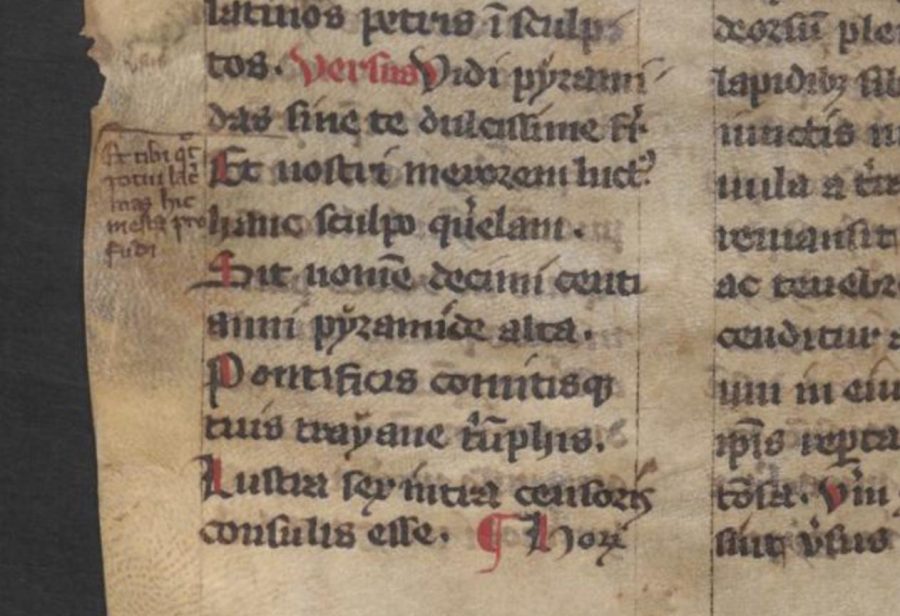

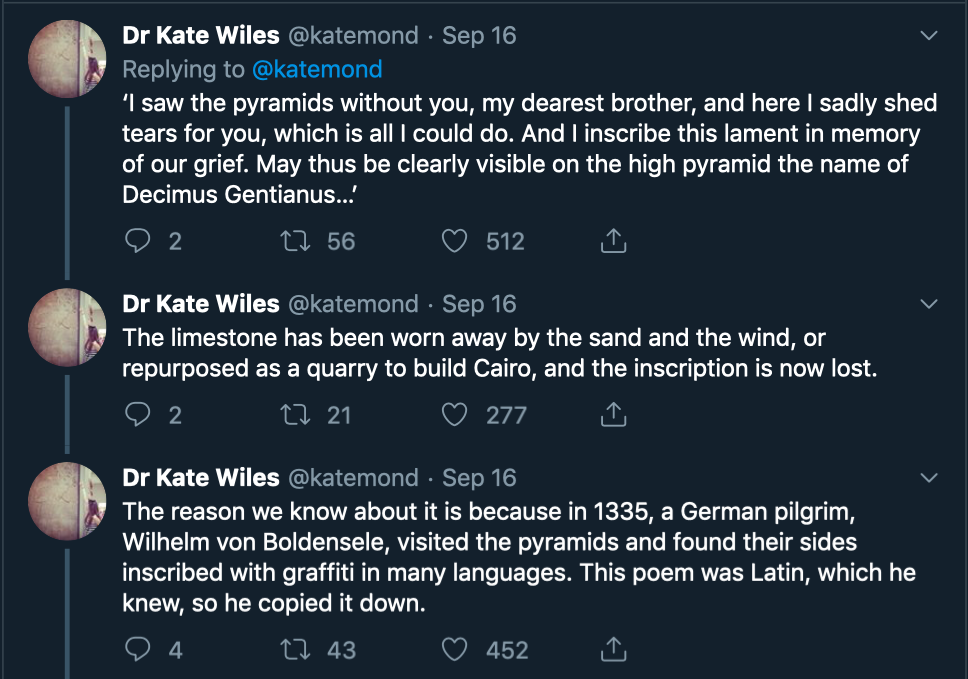

The phrase “history is written by the victors” is a cliché, which means that it is at least half true; official histories are, to a significant degree “written,” or dictated, by ruling elites. But as far as the actual writing down, and excavating, narrating, arguing about, and revising of history goes… well, that is the work of historians, who may work for powerful institutions but who are not themselves—with several notable exceptions, of course—politicians, generals, or captains of industry. This is all to the good. Historians, and Twitterstorians, can tell stories and present evidence that the victors might rather see disappear. And they can tell stories we never knew that we were missing, but which humanize the past by restoring the lives of ordinary people with ordinary concerns. Stories of everyday ancient Romans and Egyptians, for example, or of ancient Romans in Egypt, visiting and vandalizing the pyramids. In one such poignant story, circulating on Twitter, a Roman woman named Terentia carved into the limestone facing of the Great Pyramid sometime around 120 AD a touching poem for her brother, who had just recently died. As told by medievalist, linguist, and Senior Editor at History Today Dr. Kate Wiles, the poem might have been lost to the ages had it not been discovered by German pilgrim Wilhelm von Boldensele in 1335. Knowing Latin, Von Boldensele read the poem, found it moving, and copied it down. (See his manuscript at the top.) Wiles quotes a part of the prose English translation:

We can surmise that Terentia must have had some means to travel, but in Wiles' abridged Twitter version of the story, we also might assume she could be anyone at all, grieving the loss of a close relative. Terentia’s grief is no less moving or real when we learn that the inscription goes for on several lines Wiles cut for brevity.

Turning to Emily Ann Hemelrijk’s book Matrona Docta: Educated Women in the Roman Elite from Cornelia to Julia Domna, Dr. Wiles' source for the Great Pyramid poem, we find that Terentia wasn’t just an educated, upper class woman, she was a very well-connected one. The inscription goes on to identify her brother as “a pontifex and companion to your triumphs, Trajan, and both censor and consul before his thirtieth year of age.” In his anthology Women Writers of Ancient Greece and Rome, Ian Michael Plant provides even more historical context. Of Terentia, we know little to nothing save the Von Boldensele’s copy of her six hexameters (and possibly more that he ignored). Of Decimus Gentianus, however, we know that he not only served as a consul under Trajan but also as governor of Macedonia under Hadrian. Terentia “chose the pyramid for her epitaph to provide a suitably grand and everlasting site for her tribute to him,” writes Plant. (Cue Shelly’s “Ozymandias.”) Not only is the poem about a victor, but it appears to shift its address from him to the ultimate victor, Emperor Trajan, in its final lines. Should this change our appreciation of the story as a slice of Roman tourist life and example of ancient women's writing? No, but it shows us something about what history gets preserved and why. Despite historians’ best efforts, especially in public-facing work, to make the past more accessible and relatable, they, too, are limited by what other cultures chose to preserve and what to pass over. Hemelrijk admits, “the poem is no literary masterpiece,” but Von Boldersele saw enough merit in its sentiments to record it for posterity. He also made a judgment about the inscription’s historical import, given its references, which is probably the reason we have it today. via Dr. Kate Wiles Related Content: Play Caesar: Travel Ancient Rome with Stanford’s Interactive Map How the Egyptian Pyramids Were Built: A New Theory in 3D Animation Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Human All Too Human: A Roman Woman Visits the Great Pyramid in 120 AD, and Carves a Poem in Memory of Her Deceased Brother is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | A New Kurt Vonnegut Museum Opens in Indianapolis … Right in Time for Banned Books Week

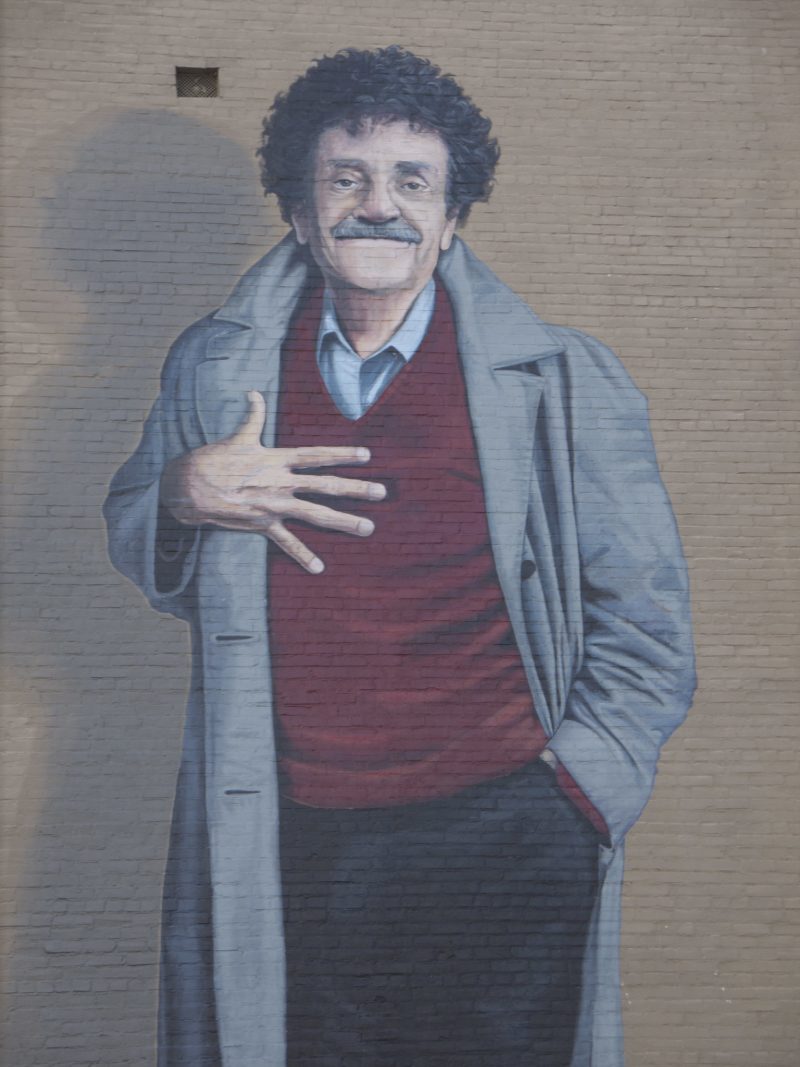

“All my jokes are Indianapolis,” Kurt Vonnegut once said. “All my attitudes are Indianapolis. My adenoids are Indianapolis. If I ever severed myself from Indianapolis, I would be out of business. What people like about me is Indianapolis.” He delivered those words to a high-school audience in his hometown of Indianapolis in 1986, and a decade later he made his feelings even clearer in a commencement speech at Butler University: "If I had to do it all over, I would choose to be born again in a hospital in Indianapolis. I would choose to spend my childhood again at 4365 North Illinois Street, about 10 blocks from here, and to again be a product of that city’s public schools." Now, at 543 Indiana Avenue, we can experience the legacy of the man who wrote Slaughterhouse-Five, Cat's Cradle, and Breakfast of Champions at the newly permanent Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library. The museum's founder and CEO Julia Whitehead "conceived the idea for a Vonnegut museum in November of 2008, a year and a half after the author’s death, writes Atlas Obscura's Susan Salaz. "The physical museum opened in a donated storefront in 2011, displaying items donated by friends or on loan from the Vonnegut family" — his Pall Malls, his drawings, a replica of his typewriter, his Purple Heart. But the collection "has been homeless since January 2019." A fundraising campaign this past spring raised $1.5 million in donations, putting the museum in a position to purchase the Indiana Avenue building, one capacious enough for visitors to, according to the museum's about page, "view photos from family, friends, and fans that reveal Vonnegut as he lived; "ponder rejection letters Vonnegut received from editors"; and "rest a spell and listen to what friends and colleagues have to say about Vonnegut and his work."

The newly re-opened Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library will also pay tribute to the jazz-loving, censorship-loathing veteran of the Second World War with an outdoor tunnel playing the music of Wes Montgomery and other Indianapolis jazz greats, a "freedom of expression exhibition" that Salaz describes as featuring "the 100 books most frequently banned in libraries and schools across the nation," and veteran-oriented book clubs, writing workshops, and art exhibitions. In the museum's period of absence, Vonnegut pilgrims in Indianapolis had no place to go (apart from the town landmarks designed by the writer's architect father and grandfather), but the 38-foot-tall mural on Massachusetts Avenue by artist Pamela Bliss. Having known nothing of Vonnegut's work before, she fell in love with it after first visiting the museum herself, she'll soon use its Indiana Avenue building as a canvas on which to triple the city's number of Vonnegut murals. You can see more of the new Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library, which opened its doors for a sneak preview this past Banned Books Week, in the video at the top of the post, as well as in this four-part local news report. Though Vonnegut expressed appreciation for Indianapolis all throughout his life, he also left the place forever when he headed east to Cornell. He also satirically repurposed it as Midland City, the surreally flat and prosaic Midwestern setting of Breakfast of Champions whose citizens only speak seriously of "money or structures or travel or machinery," their imaginations "flywheels on the ramshackle machinery of awful truth." I happen to be planning a great American road trip that will take me through Indianapolis, and what with the presence of an institution like the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library — as well as all the cultural spots revealed by the Indianapolis-based The Art Assignment — it has become one of the cities I'm most excited to visit. Vonnegut, of all Indianapolitans, would surely appreciate the irony. Related Content: Why Should We Read Kurt Vonnegut? An Animated Video Makes the Case Kurt Vonnegut Creates a Report Card for His Novels, Ranking Them From A+ to D Kurt Vonnegut: Where Do I Get My Ideas From? My Disgust with Civilization Behold Kurt Vonnegut’s Drawings: Writing is Hard. Art is Pure Pleasure 22-Year-Old P.O.W. Kurt Vonnegut Writes Home from World War II: “I’ll Be Damned If It Was Worth It” Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. A New Kurt Vonnegut Museum Opens in Indianapolis … Right in Time for Banned Books Week is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/09/26 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |