[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, October 1st, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | Quentin Tarantino Explains How to Write & Direct Movies When Quentin Tarantino debuted in 1992 with Reservoir Dogs, and even more so when he followed it up with the cinematic phenomenon that was Pulp Fiction, the viewers most dubious about the young auteur's cultural staying power dismissed his movies as elevations of style over substance. Whether or not Tarantino has converted all his early critics over the past 27 years, he's certainly demonstrated that style can constitute a substance of its own. Even many who didn't care for his latest picture, this year's Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, nevertheless expressed gratitude at the release of a lavish, large-scale film packed full of ideas, references, set pieces, and jokes — an increasingly rare achievement, or even aspiration, among non-Tarantino filmmakers. How does he do it? The Director's Chair profile video above, and the accompanying Studio Binder essay by Matt Vasiliauskas, identifies the essential elements that constitute the Tarantinian style and Tarantinian substance. In the video Tarantino discusses his process: "I was put on Earth to face the blank page," to bring forth ideas from within and place them in new genre contexts, to write one line of dialogue after another and feel the surprise as the script takes turns unexpected even to him. Everything, from conversations to action scenes to expansive wide shots, plays out in his head before he shoots the first frame: "Before I make the movie, I watch the movie." And like all auteurs, he makes the movie he wants to see: “I don’t think the audience is this dumb person lower than me," he has said. "I am the audience.” A filmmaker looking to follow Tarantino's example must do the following: "Keep it personal," using experiences they've actually had or emotions they've actually felt, even if they present them filtered through "crazy genre world." "Structure like a novel," with the willingness to break free of chronological order. "Think like an actor," since you'll have to work long and hard with them. Shoot "Hong Kong action sequences," two or three moves at a time, so that you can organically change and incorporate what happens along the way. "Keep music in mind," whether that means existing songs that evoke certain times, places, and moods, or original scores like that which Tarantino commissioned for The Hateful Eight from Ennio Morricone. Morricone is best known for his collaborations with Tarantino's hero Sergio Leone, and like Leone and "all directors working at the top of their game," writes Vasiliauskas, Tarantino "uses the camera as his most powerful storytelling implement," especially when shooting wide. "Whether it’s the Bride battling the Crazy 88 gang in Kill Bill or Django surveying a burned-out home, Tarantino understands the power of the wide-shot to not only create tension, but to utilize the environment in revealing the desires of his characters." But he also gets serious aesthetic and emotional mileage out of extreme close-ups, crash zooms, and point-of-view shots from inside the trunk of a car (or period equivalents thereof). Above all, this former Manhattan Beach video-store clerk "absorbs movies," and has by his own admission stolen from more films than most of us will watch in our lives. But none of this makes predictable what Tarantino will draw from his real-life and filmgoing experiences and put on the screen next: "I should throw them for a loop," he says in an interview clip included in the video. He means his audience, of course, but before he can throw us for a loop, he has to do it to himself. And whatever thrills and surprises Tarantino will, as we've seen over the course of ten feature films so far, thrill and surprise us even more. Related Content: How Quentin Tarantino Steals from Other Movies: A Video Essay The Films of Quentin Tarantino: Watch Video Essays on Pulp Fiction, Reservoir Dogs, Kill Bill & More Quentin Tarantino Explains The Art of the Music in His Films Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Quentin Tarantino Explains How to Write & Direct Movies is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | A 900-Page Pre-Pantone Guide to Color from 1692: A Complete Digital Scan

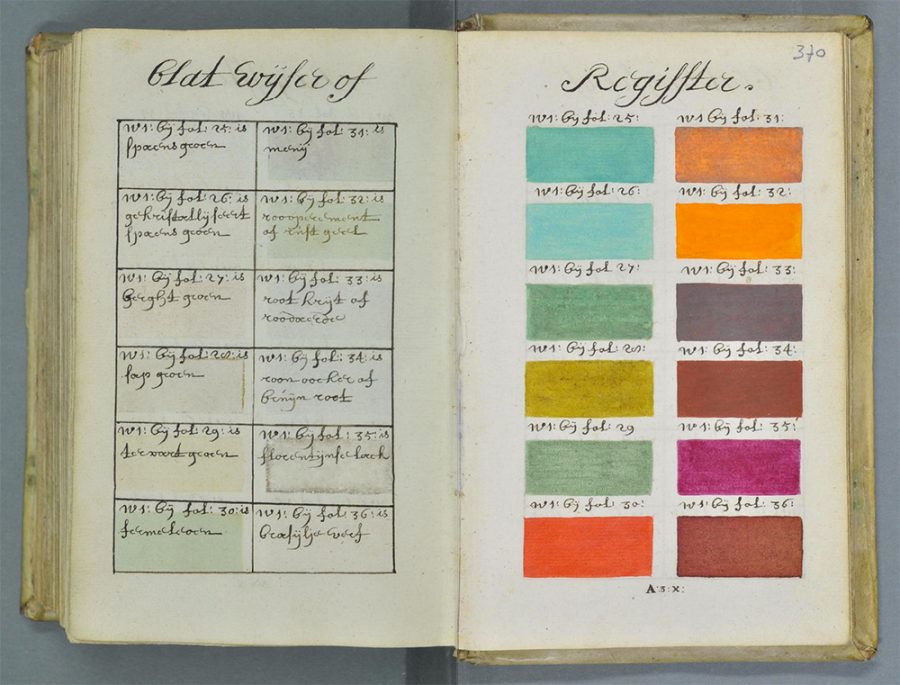

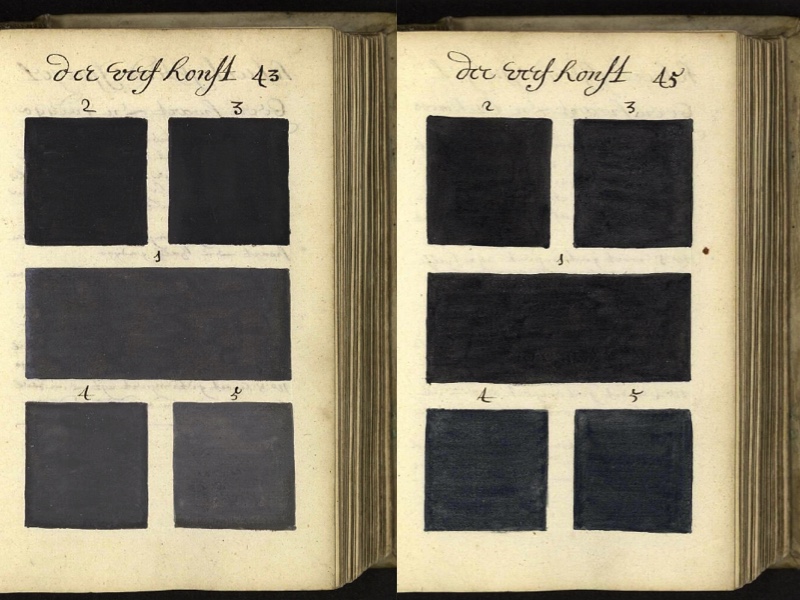

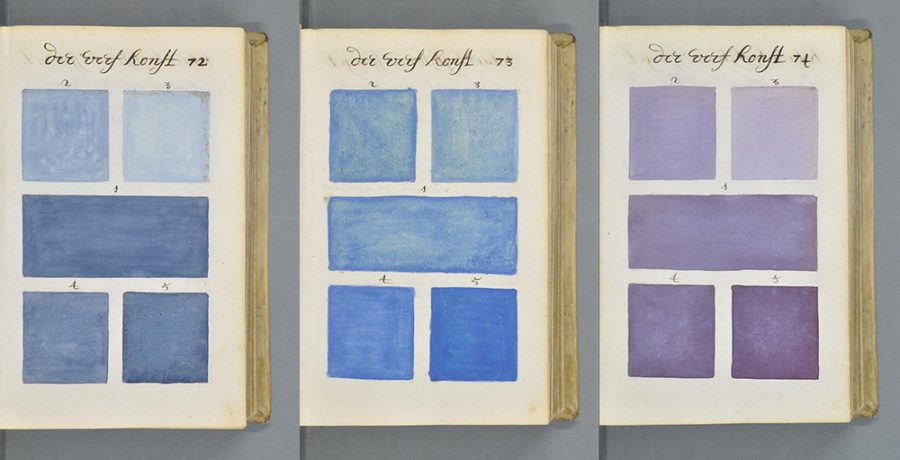

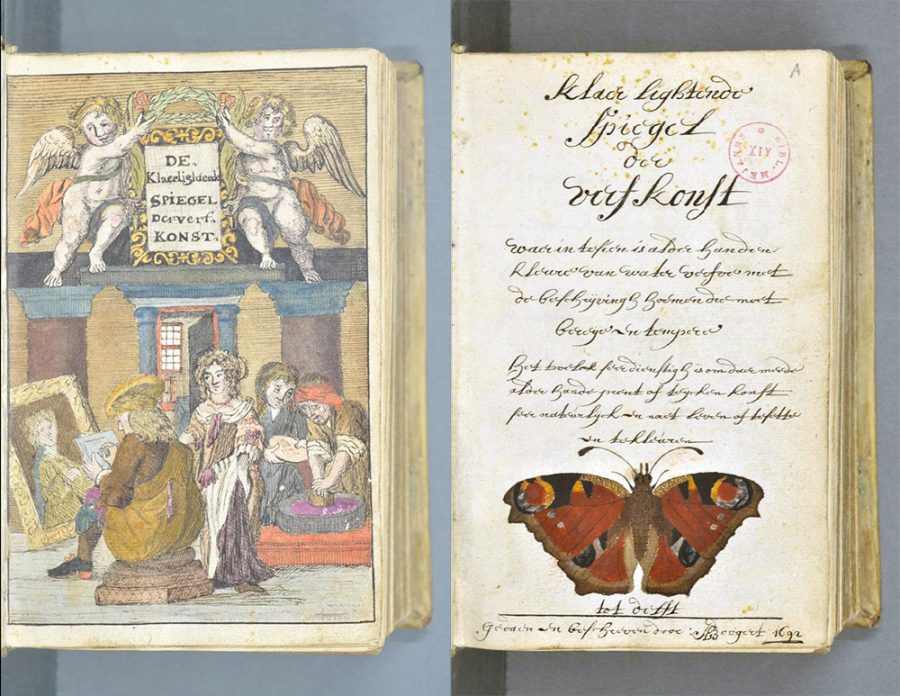

Human beings got along perfectly well for hundreds of millennia without standardized taxonomies of color, but they didn’t do so in a globally connected culture full of logos, brands, and 24/7 screens. It’s arguable whether the world as we now see it would have been possible without monopolistic color systems like Pantone. They may circumscribe the visual world and dictate color from above. But they also enable international design principles and visual languages that translate easily everywhere. These circumstances did not yet exist in 1692, when Dutch artist A. Boogert created a huge, almost 900-page book on color, Traité des couleurs servant à la peinture à l'eau. But they were slowly coming into being, thanks to studies by philosopher-scientists like Isaac Newton. Boogert’s book took enlightenment work on optics in a more rigorous design direction than any of his contemporaries, anticipating a number of influential books on color to come in the following centuries, such as the art history-making studies by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and a book on color used by Charles Darwin during his Beagle voyage.

Boogert’s exhaustive study includes handwritten notes and descriptions and hundreds of hand-painted color swatches. This above-and-beyond effort was not, however, made for scientific or industrial purposes but as a guide for artists, showing how to mix watercolors to make every color in the spectrum. The author even includes a comprehensive unit on whites, grays, and blacks. How much historical influence did Boogert’s text have on the development of standardized color systems, we might wonder? Hardly any at all. Its single copy, notes This is Colossal, “was probably seen by very few eyes.”

The obscure book disappeared in the archives of the Bibliothèque Méjanes in Aix-en-Provence, France. That is, until its discovery recently by Medieval book historian Erik Kwakkel, who posted scans on his Tumblr and translated some of the introduction from the original Dutch. Since then, the complete text has come online: 898 pages of high-resolution digital scans at the Bibliothèque Méjanes site. (Go to this page, click on the picture, then click on the arrows in the lower right side of the page to move through the book.) If you read Dutch, all the better to appreciate this rare historic artifact. But you don’t need to understand A. Boogert’s explanations on watercolor technique to be staggered by the incredible amount of work that went into this early, overlooked labor of love for systematic approaches to color. Enter the full text here.

Related Content: The Vibrant Color Wheels Designed by Goethe, Newton & Other Theorists of Color (1665-1810) Goethe’s Theory of Colors: The 1810 Treatise That Inspired Kandinsky & Early Abstract Painting Werner’s Nomenclature of Colour, the 19th-Century “Color Dictionary” Used by Charles Darwin (1814) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness A 900-Page Pre-Pantone Guide to Color from 1692: A Complete Digital Scan is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | Watch Queen Rehearse & Meticulously Prepare for Their Legendary 1985 Live Aid Performance It seems no small irony that lean, late-seventies and eighties New Wave bands like U2, Depeche Mode, and the Cure, who made legacy stadium rock acts like Queen seem outmoded, went on to become massive-selling stadium legacy acts themselves. The musical critique of 70’s rock excesses found its most popular expression in bands that took a lot from Freddie Mercury and company: flamboyant sexual fluidity, spectacular light shows, raw emotional confessionalism, stridently sentimental, fist-pumping anthems... Yet in the eighties, a “wide-sweeping change in musical tastes” displaced Queen’s reign on the charts, writes Lesley-Ann Jones in Mercury: An Intimate Biography of Freddie Mercury. They were “confoundingly on the wane” and “were beginning to feel that they’d had their day. A permanent split was in the cards. They’d talked about it.” But it was not to be, thanks to Live Aid, the near-mythological July 13, 1985 performance at Wembley Stadium. After that gig, remembers Queen keyboardist Spike Edney, “Queen found that their whole world had changed.” Suddenly, after their short, 20-minute daylight set (see the video at the bottom), they were again the biggest band on the planet. “Queen smoked ‘em,” as Dave Grohl puts it. “They walked away being the greatest band you’d ever seen in your life, and it was unbelievable.” The sentiment was universally echoed by everyone from Elton John to Bowie to Bono to Paul McCartney, all of them upstaged that day. “It has been repeated ad nauseam,” writes Jones, “that Queen’s performance was the most thrilling, the most moving, the most memorable, the most enduring—surpassing as it did the efforts of their greatest rivals.” The band, however, was “surprised that everyone was surprised,” says Edney. “They were veterans at stadium gigs… this was their natural habitat.” Queen “could practically do this stuff in their sleep.” Mixing his metaphors, Edney also reveals just how hard the band worked to remain the consummate professionals they were: “to them, it was another day at the office.” As such, they put in their time to make absolutely certain that they would be in top form. “They booked out the 400-seat Shaw Theatre, near King’s Cross train station in London,” notes Martin Chilton at Udiscovermusic, “and spent a week honing their five-song set," planning every single part of it to perfection. Live Aid organizer Bob Geldof had asked bands not to debut new material but play fan favorites. Edney was “stunned to hear certain artists belting out their latest single.” But Queen took Geldof’s “message to heart,” putting together a carefully curated medley of their biggest hits. In the video at the top of the post, see the band discuss this behind-the-scenes process with an interviewer before going onstage in front of a crowd of “the 72,000 fans who would be at Wembley—and the estimated 1.9 billion people watching on television from 130 countries around the world.” In answer to a question about going onstage without their usual spectacular stage and light show, or even time for a sound check before their set, Brian May replies, “it all comes down to whether you can play or not, really, which is nice, in a way, because I think there’s probably an element who think that groups like us can’t do it without the extravagant backdrop.” Whoever he might have been referring to, his “We’ll see” sounds supremely confident. The band was meticulously prepared. After the interview, we see rehearsal footage of nearly their full set, beginning with “Radio Ga Ga,” a song whose chorus during the live event produced what was described as “the note heard around the world.” (See it above.) After their incredible performance May sounded much more modest, even self-effacing. “The rest of us played OK, but Freddie went out there and took it to another level. It wasn’t just Queen fans. He connected with everyone. I’d never seen anything like that in my life.” The performance is all the more remarkable for the fact that Queen had been shunned just the previous year for breaking the boycott and playing in South Africa, for noble but misunderstood reasons at the time. They were considering calling it quiets, but the pressures they were under seemed only to galvanize them into what everyone remembers as their greatest show ever—”Queen’s ultimate moment,” writes Jones, “towards which they had been building their entire career.” Related Content: Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Watch Queen Rehearse & Meticulously Prepare for Their Legendary 1985 Live Aid Performance is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/10/01 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |