[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, October 2nd, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | 19th-Century Skeleton Alarm Clock Reminded People Daily of the Shortness of Life: An Introduction to the Memento Mori

Victorian culture can seem grim and even ghoulish to us youth-obsessed, death-denying 21st century moderns. The tradition of death photography, for example, both fascinates and repels us, especially portraiture of deceased children. But the practice “became increasingly popular,” notes the BBC, as “Victorian nurseries were plagued by measles, diphtheria, scarlet fever, rubella—all of which could be,” and too often were, “fatal.” Adults did not fare much better when it came to the epidemic spread of killer diseases. Surrounded inescapably by death, Victorians coped by investing their world with totemic symbols, cultural artifacts known as memento mori, meaning “remember, you must die.” Tuberculosis, cholera, influenza… at any moment, one might take ill and waste away, and there would likely be little medical science could do about it. Perhaps the best approach, then, was an acceptance of death while in the bloom of health, in order to not waste the moment and to learn to pay attention to what mattered while one could. Memento mori drawings, paintings, jewelry, photographs, and trinkets have populated European cultural history for centuries; death as an ever-present companion, not to be hidden away and feared but solemnly, respectfully given its due.

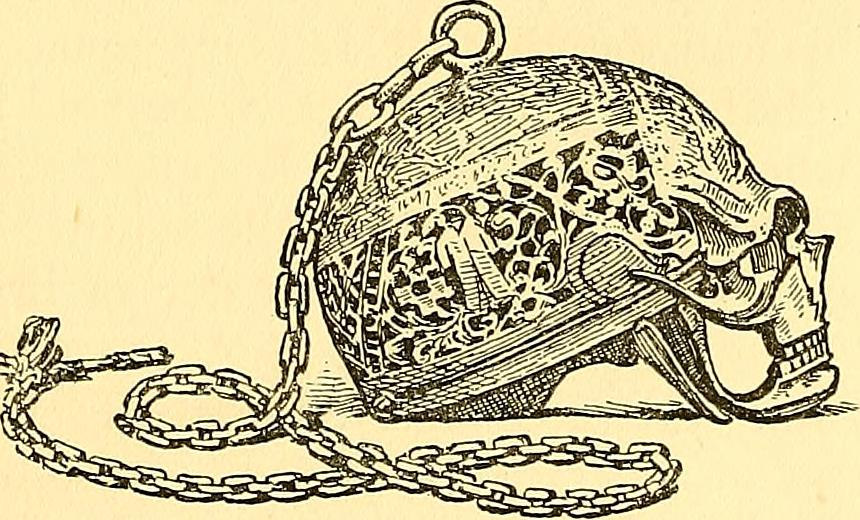

Or maybe not so respectfully, as the case may be. Some of these novelties, like the skeleton alarm clock at the top, look more like they belong at the bottom of a fish tank than a proper parlor mantle. “Presumably when the alarm went off,” writes Allison Meier at Hyperallergic, “the skeleton would shake its bones.” Wake up, life is short, you could die at any time. “Part of the collections of Science Museum, London, it’s believed to be of English origin and date between 1840 and 1900.” The Tim Burton-esque tchotchke appeared in a 2014 British Library exhibit called Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination, with many other such objects of varying degrees of artistry: “200 objects from a span of 250 years, all centered on the Gothic tradition in art, literature, music, fashion, and most recently film.” Memento mori artifacts offer visceral reminders that real, daily confrontations with disease and death were “at the base of much of Gothic literature and art.” Where we now tend to read the Gothic as primarily reflective of social, cultural, and religious anxieties, the prevalence of memento mori in European homes both low and high (such as Mary Queen of Scots' skull watch, in an 1896 illustration above) shows us just how much the gloomy strain of thinking that became the modern horror genre derives from a desire to confront mortality head on, so to speak, and finding that looking death in the face brings on ancient uncanny dread as much as healthy gallows humor and stoic, stiff-upper-lip reckoning with the ultimate fact of life. Related Content: An Artist Crochets a Life-Size, Anatomically-Correct Skeleton, Complete with Organs Celebrate The Day of the Dead with The Classic Skeleton Art of José Guadalupe Posada Old Books Bound in Human Skin Found in Harvard Libraries (and Elsewhere in Boston) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness 19th-Century Skeleton Alarm Clock Reminded People Daily of the Shortness of Life: An Introduction to the Memento Mori is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | The First Music Streaming Service Was Invented in 1881: Discover the Théâtrophone

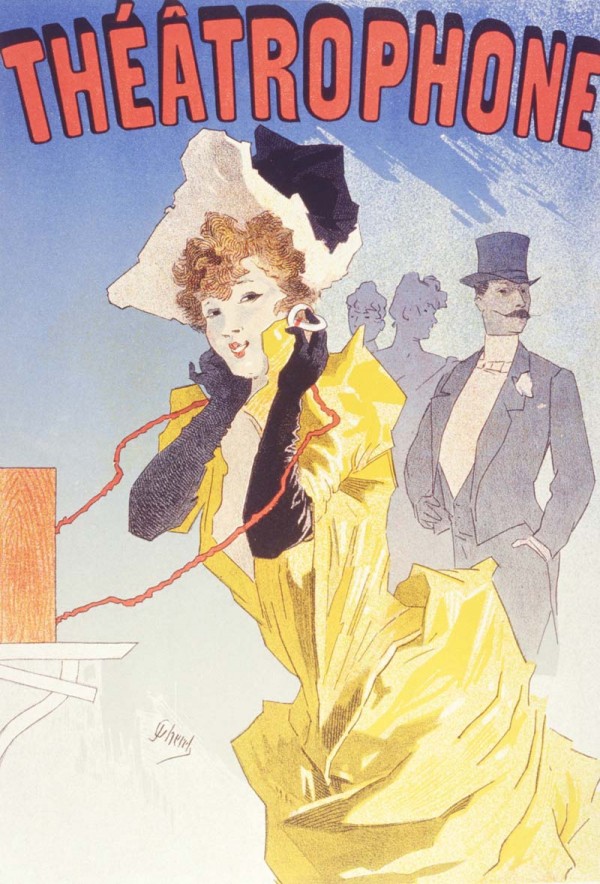

Every living adult has witnessed enough technological advancement in their lifetime to marvel at just how much has changed, and digital streaming and telecommunications happen to be areas where the most revolutionary change seems to have taken place. We take for granted that the present resembles the past not at all, and that the future will look unimaginably different. So the narrative of linear progress tells us. But that story is never as triumphantly simple as it seems. In one salient counterexample, we find that not only did livestreaming music and news exist in theory long before the internet, but it existed in actual practice—at the very dawn of recording technology, telephony, and general electrification. First developed in France in 1881 by inventor Clement Ader, who called his system the Théâtrophone, the device allowed users to experience “the transmission of music and other entertainment over a telephone line,” notes the site Bob’s Old Phones, “using very sensitive microphones of [Ader’s] own invention and his own receivers.” The pre-radio technology was ahead of its time in many ways, as Michael Dervan explains at The Irish Times. The Théâtrophone “could transmit two-channel, multi-microphone relays of theatre and opera over phone lines for listening on headphones. The use of different signals for the two ears created a stereo effect.” Users subscribed to the service, and it proved popular enough to receive an entry in the 1889 edition of The Electrical Engineer reference guide, which defined it as “a telephone by which one can have soupçons of theatrical declamation for half a franc.” In 1896 "the Belle Epoque pop artist Jules Cheret immortalized the theatrophone," writes Tanya Basu at Mental Floss, "in a lithograph featuring a woman in a yellow dress, grinning as she presumably listened to an opera feed." Victor Hugo got to try it out. "It’s very strange," he wrote. "It starts with two ear muffs on the wall, and we hear the opera; we change earmuffs and hear the French Theatre, Coquelin. And we change again and hear the Opera Comique. The children and I were delighted.” Though The Electrical Engineer also called it “the latest thing to catch [Parisians’] ears and their centimes,” the innovation had already by that time spread elsewhere in Europe. Inventor Tivador Puskas created a “streaming” system in Budapest called Telefon Hermondo (Telephone Herald), Bob's Old Phones points out, “which broadcast news and stock market information over telephone lines.” Unlike Ader’s system, subscribers could “call in to the telephone switchboard and be connected to the broadcast of their choice. The system was quite successful and was widely reported overseas.” The mechanism was, of course, quite different from digital streaming, and quite limited by our standards, but the basic delivery system was similar enough. A third such service worked a little differently. The Electrophone system, formed in London in 1884, combined its predecessors' ideas: broadcasting both news and musical entertainment. Playback options were expanded, with both headphones and a speaker-like megaphone attachment. Additionally, users had a microphone so that they could “talk to the Central Office and request different programs.” The addition of interactivity came at a premium. “The Electrophone service was expensive,” writes Dervan, “£5 a year at a time when that sum would have covered a couple months rent.” Additionally, “the experience was communal rather than solitary.” Subscribers would gather in groups to listen, and “some of the photographs” of these sessions resemble “images of addicts in an old-style opium den”—or of Victorians gathered at a séance. The company later gave recuperating WWI servicemen access to the service, which heightened its profile. But these early livestreaming services—if we may so call them—were not commercially viable, and “radio killed the venture off in the 1920s” with its universal accessibility and appeal to advertisers and governments. This seeming evolutionary dead end might have been a distant ancestor of streaming live concerts and events, though no one could have foreseen it at the time. No one save science fiction writers. Edward Bellamy’s 1888 utopian novel Looking Backward imagined a device very like the Théâtrophone in his vision of the year 2000. And in 1909, E.M. Forster drew on early streaming services and other early telecommunications advances for his visionary short story “The Machine Stops,” which extrapolated the more isolating tendencies of the technology to predict, as playwright Neil Duffield remarks, “the internet in the days before even radio was a mass medium.” Related Content: The History of the Internet in 8 Minutes Hear the First Recording of the Human Voice (1860) How an 18th-Century Monk Invented the First Electronic Instrument Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The First Music Streaming Service Was Invented in 1881: Discover the Théâtrophone is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | Metropolis Remixed: Fritz Lang’s German Expressionist Sci-Fi Classic Gets Fully Colorized and Dubbed Those of us who grew up with late-night cable television will have a few memories of happening upon old movies that didn't look quite right. Usually drawn from the 1940s or 50s, and sometimes from the depths of genres like science-fiction and horror, these pictures had undergone the process of colorization in hopes of increasing their appeal to a generation unused to black-and-white imagery. Alas, even the most high-profile colorization projects back then tended to look washed-out, with lifelessly pale faces lost among washes of green and brown. On the technical level colorization has improved in the decades since, though on the artistic level its usage remains, to say the least, a suspect endeavor. But what if the film chosen for colorization was, rather than some piece of drive-in schlock, one of the acknowledged masterpieces of early 20th-century cinema? MetropolisRemix comes as one especially intriguing (if also startling) answer to that question, bringing as it does Fritz Lang's hugely influential 1927 work of German Expressionist sci-fi from not just the world of black-and-white film into color but from that of silent film into sound. To add color its makers used DeOldify, "a deep learning-based project for colorizing and restoring old images (and video!)" previously featured here on Open Culture when we posted this colorized footage of Paris, New York, and Havana from the late 19th and early 20th century. You can get a taste of the MetropolisRemix viewing experience from this trailer: In its entirety this version of Metropolis runs just over two hours, quite a bit shorter than the film's most recent restoration, 2010's The Complete Metropolis. The difference owes in large part to the lack of dialogue-conveying intertitles, which have been rendered unnecessary by a full-cast English-language dub that includes music and sound effects. Not everyone, of course, will approve of this "fan modernization," as its creators describe it. Phil Hall at Cinema Crazed prefers to call it "the most recklessly bad idea for a film since All This and World War II, the infamous 1976 nonsense that united Second World War newsreel footage with mostly unsatisfactory cover versions of Beatles music." But the sheer brazenness of MetropolisRemix nevertheless impresses — and somehow, Lang and his collaborators' vision of an industrial art-deco dystopia survives. via Messy Nessy Related Content: Metropolis: Watch a Restored Version of Fritz Lang's Masterpiece (1927) Read the Original 32-Page Program for Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) Fritz Lang Invents the Video Phone in Metropolis (1927) H.G. Wells Pans Fritz Lang’s Metropolis in a 1927 Movie Review: It’s “the Silliest Film” 10 Great German Expressionist Films: From Nosferatu to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Metropolis Remixed: Fritz Lang’s German Expressionist Sci-Fi Classic Gets Fully Colorized and Dubbed is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/10/02 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |