[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, October 22nd, 2019

| Time | Event |

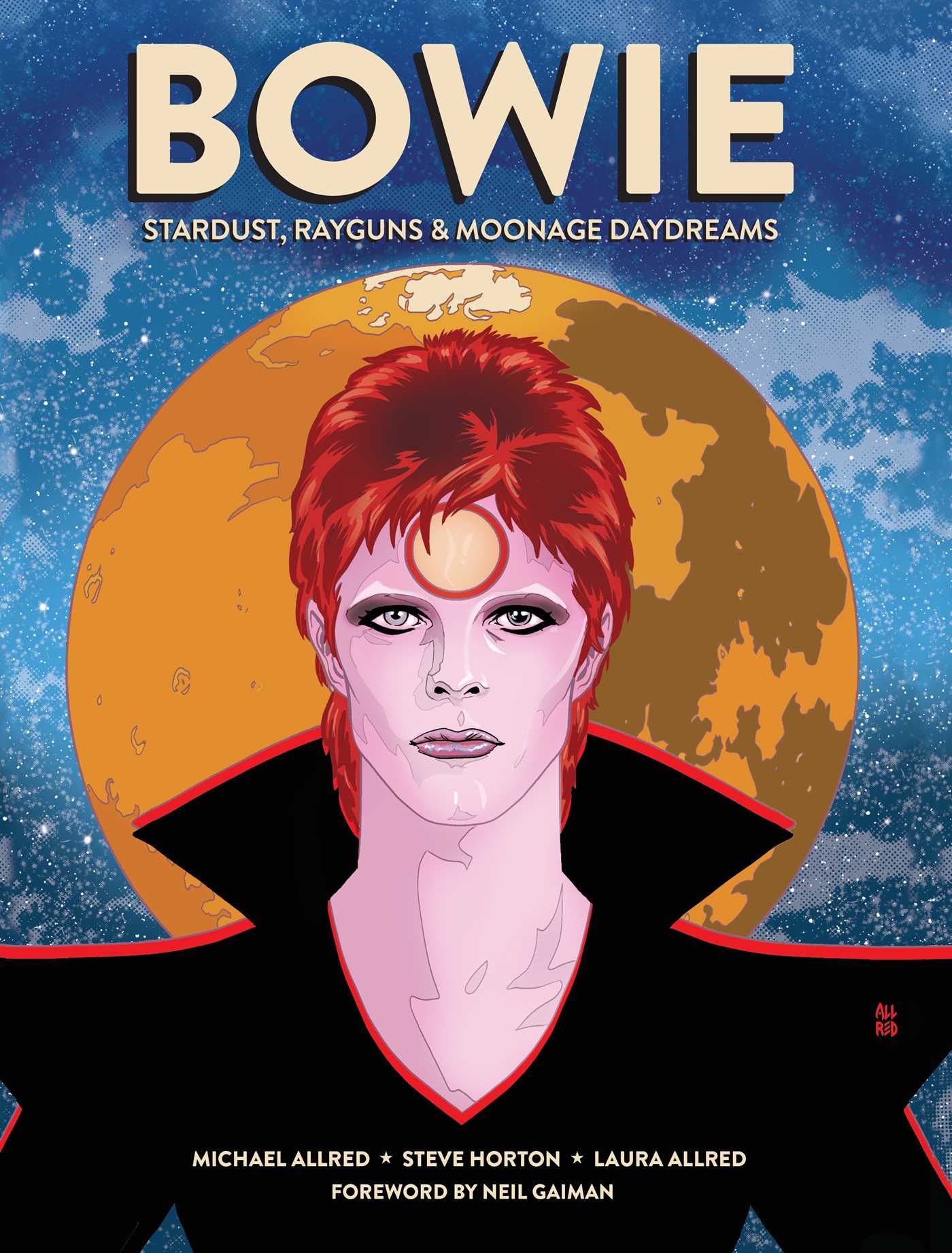

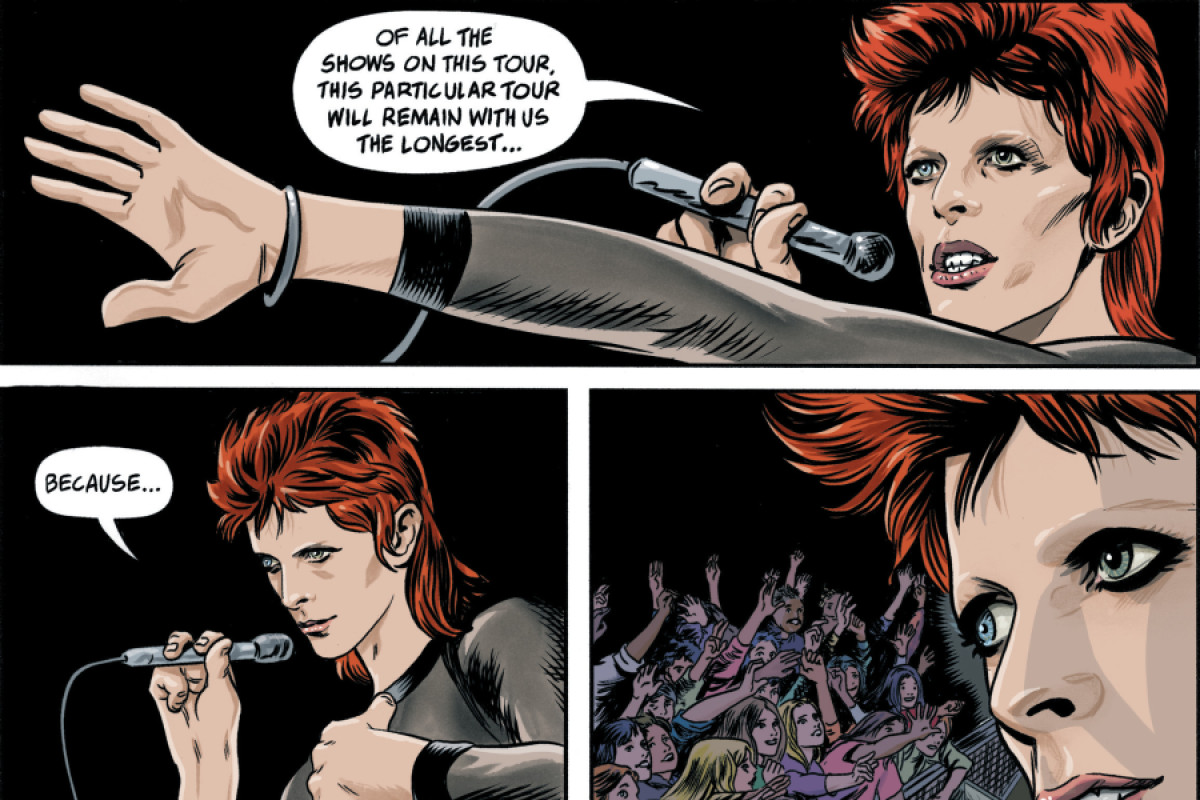

| 8:00a | The Story of Ziggy Stardust Gets Chronicled in a New Graphic Novel, Featuring a Forward by Neil Gaiman

Film has always been a medium that seeks to entertain as well as edify, framing thrills and chills for profit, and framing compositions deserving of the label of “art.” Very often it has done both at the same time. Every casual student of the medium will, at least, admit this much. But never have the differences between movie art and entertainment seemed as magnified and polarized as they are now, in the midst of debates about comic book franchises and the fine art we call cinema. Whatever the reasons, film has not reached the détente between art and entertainment achieved by popular music—another medium dependent on late-19th/20th century recording technologies and born of a thoroughly modern commercial matrix. Of course, not all pop aspires to art. But the idea that music can be hugely entertaining—drawing on the “low” genres of fantasy, science fiction, and comic books—and also worthy of cultural immortality has become uncontroversial in large part because of the career of one musician. David Bowie, rock and roll’s original space alien superhero, used his bankable personae through the decades to give credence to the idea of “art rock,” to realize its glam possibilities, to turn the rock auteur into an actor. He learned from a host of experimenters, both his direct influences and his spiritual predecessors. And he inspired a legion of successors who weren’t afraid to play characters in their work, to mix interests in philosophy, literature, and the occult with the flamboyant, campy styles of the comics. (A mix comics themselves played with in both popular and underground manifestations.)

Bowie embodied the future when he appeared on the scene as Ziggy in 1972, after years of laboring in obscurity and a few fleeting brushes with fame. “The incarnations of David Bowie were, in themselves, science fictional, “writes Neil Gaiman in the forward to a new graphic novel, BOWIE: Stardust, Rayguns, & Moonage Daydreams, which tells the story of Bowie’s rise as Ziggy. “All I was missing was a Bowie comic,” says Gaiman of his own fandom. “And, missing it, I would draw bad Bowie comics myself.” Ziggy Stardust especially called for such treatment. Bowie wore the glam rock Martian mask with such commitment no one doubted that he meant it—only what, exactly, he meant by it. “He defied classification,” notes Simon & Schuster, “with his psychedelic aesthetics, his larger-than-life image, and his way of hovering on the border of the surreal.” Fittingly, the comic is drawn by an artist who realized a psychedelic, surrealist creative vision of Neil Gaiman’s: Michael Allred, who worked on the Sandman series. The story, “part biography and part imagination,” reports Rolling Stone, is written by Steve Horton and colored by Laura Allred. Insight comics will release the book on January 7th, 2020. Preorder a copy here. via Rolling Stone Related Content: 96 Drawings of David Bowie by the “World’s Best Comic Artists”: Michel Gondry, Kate Beaton & More David Bowie Songs Reimagined as Pulp Fiction Book Covers: Space Oddity, Heroes, Life on Mars & More Freddie Mercury Reimagined as Comic Book Heroes Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Story of Ziggy Stardust Gets Chronicled in a New Graphic Novel, Featuring a Forward by Neil Gaiman is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | The First Faked Photograph (1840) The photograph was invented in the early 19th century, but who invented it? Histories of photography point to several different independent inventors, most of them French: Nicéphore Niépce, for example, who in 1826 made the first work recognizable as a photograph, or more famously Louis Daguerre, honored for his invention of the daguerreotype photographic process by the French Academy of Sciences and the Académie des Beaux Arts in 1839. But what about Daguerre's contemporary Hippolyte Bayard, who had also been developing and refining his own form of photography? After going unacknowledged by the Academy, he had only one option left: suicide. The Vox Darkroom video above tells the story of Bayard's 1840 Self Portrait as a Drowned Man, which depicts exactly what its title suggests: Bayard's corpse, retrieved from the water and propped up unclaimed at the morgue. "The Government which has been only too generous to Monsieur Daguerre, has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself," reads the note on the back of the photograph. "Oh the vagaries of human life....!" A sorry tale, to be sure, and of a kind not unknown in the history of invention. But wait: how could a dead man shoot a "self-portrait"? And if indeed "no-one has recognized or claimed him," as the note adds, who would have bothered to write the note itself? Bayard, still very much alive, made Self Portrait as a Drowned Man as a kind of artistic stunt, the latest in a series of self-portraits testing his photographic process. The "morgue" shot contains some of the artifacts in its predecessors, including a garden statue, a floral vase, and Bayard's signature broad straw hat. (Even the expression of death was of a piece with his previous self-portraits: the long exposure time meant he'd had to hold absolutely still with his eyes closed in all of them as well.) Until his death in 1887 — long after Daguerre had passed — Bayard continued experimenting with photography, creating reality-departing images including "double self portraits." If he couldn't go down as the inventor of the photograph, at least he could go down as the inventor of the fake photograph — a still-relevant invention, to say the least, given our increasingly complicated relationship with the truth in the 21st century. Related Content: The First Photograph Ever Taken (1826) See the First Photograph of a Human Being: A Photo Taken by Louis Daguerre (1838) See The First “Selfie” In History Taken by Robert Cornelius, a Philadelphia Chemist, in 1839 Artificial Intelligence Creates Realistic Photos of People, None of Whom Actually Exist The History of Photography in Five Animated Minutes: From Camera Obscura to Camera Phone Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The First Faked Photograph (1840) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

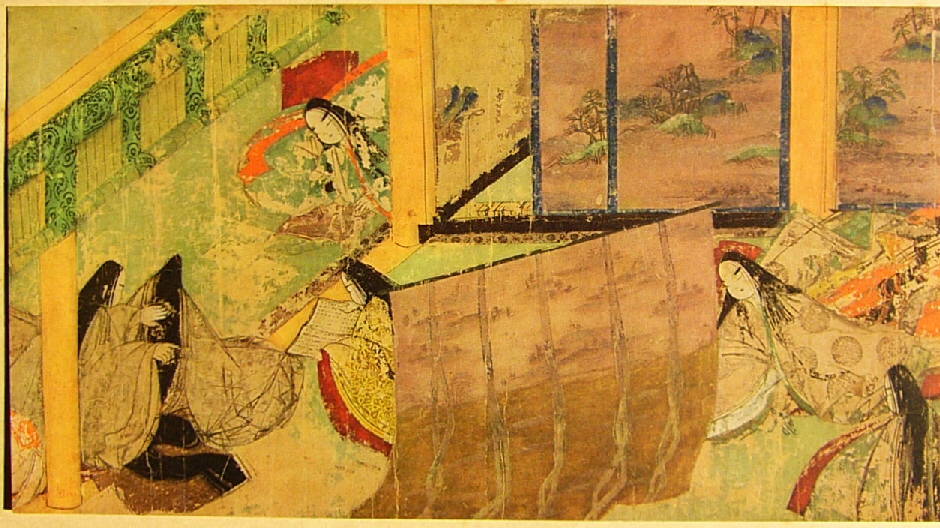

| 7:21p | Found: A Long Lost Chapter from the World’s Oldest Novel, the 11th-Century Japanese Classic, The Tale of Genji

Henry James’ disparagement of Victorian novels has always struck me as odd. “What do such large loose baggy monsters,” as he called them, “with their queer elements of the accidental and the arbitrary, artistically mean?” The question might be asked of what has often been considered the first modern novel, Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, a tragic-comic adventure whose first volume ranges over 52 loose, episodic chapters and whose second appeared ten years later to comment explicitly on the first’s success. And then, six-hundred years earlier, there appeared what many consider to be the first novel ever written, The Tale of Genji, which “covers almost three quarters of a century,” notes translator Edward Seidensticker in an introduction to his 1976 edition. “The first forty-one chapters have to do with the life and loves of the nobleman known as ‘the shining Genji,’” the son of an emperor. We follow Genji from birth to his 52nd year, then the final ten chapters relate the tale of Kaoru, “who passes in the world as Genji’s son but is really the grandson of his best friend.” (See a 12th-century illustration from the tale above.) Written by a noblewoman and lady of the court in 11th century Heian Japan, the book’s author is called Murasaki Shikibu, but her real name is unknown. Shikibu “designates an office held by her father”; Murasaki probably derives from the name of a main character in the novel. There is no “conclusive evidence that the Genji was either finished or unfinished at the time, nor is there conclusive evidence that it is finished or unfinished today.” Some chapters have been thought spurious, some deemed missing. No original manuscript exists, and only four of the novel’s 54 chapters have been authenticated as transcriptions from the original text. That is, until this month, when a “lost”—or previously unknown—chapter surfaced, and “is now the fifth confirmed transcription of the historical novel,” as Hakim Bishara writes at Hyperallergic. “The newly discovered chapter, titled ‘Wakamurasaki,’ depicts Genji’s encounter with Murasaki-no-ue, the young woman who later becomes his wife.” It was discovered by Motofuyu Okochi, The Japan Times reports, “a descendent of the former feudal lord of the Mikawa-Yoshida Domain in Aichi Prefecture.” The new Genji material appears “in one chapter of a five-chapter work called ‘Aobyoshibon’ (blue cover book), compiled by poet Fujiwara Teika,” who is believed to have transcribed the oldest documented versions of the novel during the Kamakura Period (1185-1333). There is as yet no critical discussion of how this find might change the way scholars read the book, but as a loose baggy monster, it can expand and contract, change its shape and composition, without losing its essential character. As Seidensticker writes, “Murasaki Shikibu was no Aristotelian, planning her beginning, middle, and end before she set brush to paper. The Genji is full of hesitations and wrong turns and retreats.” Full, in other words, of the meanderings of the mind. (You can read Seidensticker’s translation of the Genji online here.) Another Western admirer of the novel, Jorge Luis Borges, writing of an earlier translation, put it another way: “What interests us is not the exoticism—the horrible word—but rather the human passions… Murasaki’s work is what one would quite precisely call a psychological novel.” via Hyperallergic Related Content: Hand-Colored Photographs of 19th Century Japan Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Found: A Long Lost Chapter from the World’s Oldest Novel, the 11th-Century Japanese Classic, The Tale of Genji is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/10/22 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |