[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, October 24th, 2019

- Sister Carrie, by Theodore Dreiser

- The Life of Jesus, by Ernest Renan

- A Doll's House, by Henrik Ibsen

- Winesburg, Ohio, by Sherwood Anderson

- The Old Wives' Tale, by Arnold Bennett

- The Maltese Falcon, by Dashiel Hammett

- The Red and the Black, by Stendahl

- The Short Stories of Guy De Maupassant, translated by Michael Monahan

- An Outline of Abnormal Psychology, edited by Gardner Murphy

- The Stories of Anton Chekhov, edited by Robert N. Linscott

- The Best American Humorous Short Stories, edited by Alexander Jessup

- Victory, by Joseph Conrad

- The Revolt of the Angels, by Anatole France

- The Plays of Oscar Wilde

- Sanctuary, by William Faulkner

- Within a Budding Grove, by Marcel Proust

- The Guermantes Way, by Marcel Proust

- Swann's Way, by Marcel Proust

- South Wind, by Norman Douglas

- The Garden Party, by Katherine Mansfield

- War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy

- John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley: Complete Poetical Works

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | F. Scott Fitzgerald Creates a List of 22 Essential Books (1936)

Fitzgerald had moved into Asheville's Grove Park Inn that April after transferring his wife Zelda, a psychiatric patient, to nearby Highland Hospital. It was the same month that Esquire published his essay "The Crack Up", in which he confessed to a growing awareness that "my life had been a drawing on resources that I did not possess, that I had been mortgaging myself physically and spiritually up to the hilt." Fitzgerald's financial and drinking problems had reached a critical stage. That summer he fractured his shoulder while diving into the hotel swimming pool, and sometime later, according to Michael Cody at the University of South Carolina's Fitzgerald Web site, "he fired a revolver in a suicide threat, after which the hotel refused to let him stay without a nurse. He was attended thereafter by Dorothy Richardson, whose chief duties were to provide him company and try to keep him from drinking too much. In typical Fitzgerald fashion, he developed a friendship with Miss Richardson and attempted to educate her by providing her with a reading list." It's a curious list. Shakespeare is omitted. So is James Joyce. But Norman Douglas and Arnold Bennett make the cut. Fitzgerald appears to have restricted his selections to books that were available at that time in Modern Library editions. At the top of the page, Richardson writes "These are books that Scott thought should be required reading." Note: We have provided links to texts available online. Most appear in our collection, 800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices. Courses on Fitzgerald and contemporaries can be found in the Literature section of our Free Online Courses collection. An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in August 2013. via The University of South Carolina Related Content: Ernest Hemingway Creates a Reading List for a Young Writer, 1934 Seven Tips From F. Scott Fitzgerald on How to Write Fiction Rare Footage of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald From the 1920s F. Scott Fitzgerald Creates a List of 22 Essential Books (1936) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

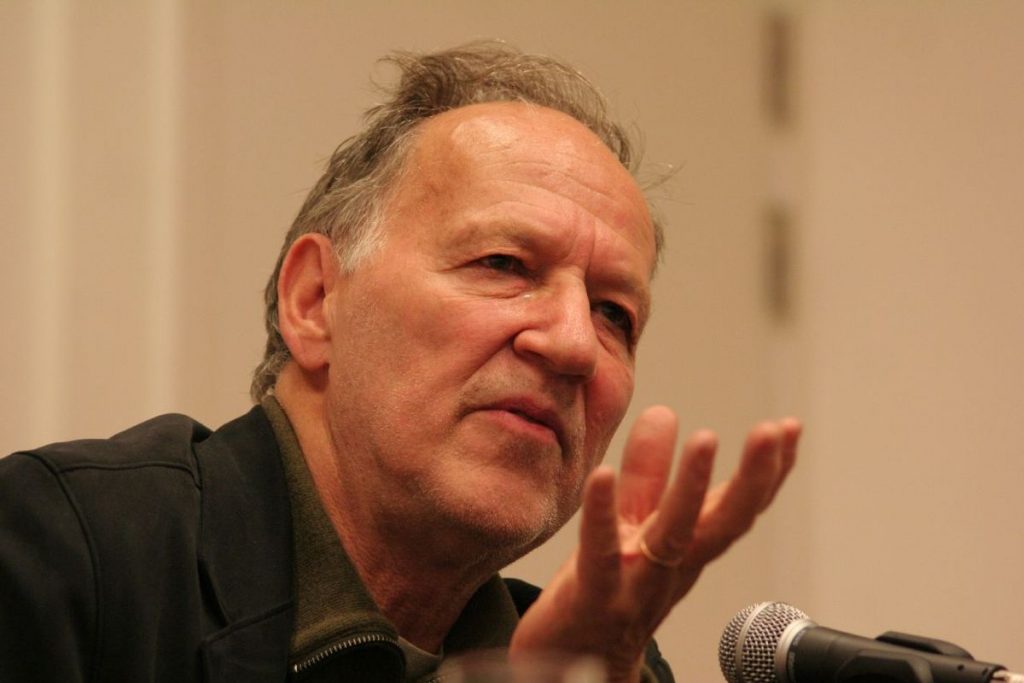

| 11:00a | Werner Herzog Offers 24 Pieces of Filmmaking and Life Advice

Image by Erinc Salor via Wikimedia Commons There are few filmmakers alive today who have the mystique of Werner Herzog. His feature films and his documentaries are brilliant and messy, depicting both the ecstasies and the agonies of life in a chaotic and fundamentally hostile universe. And his movies seem very much to reflect his personality – uncompromising, enigmatic and quite possibly crazy. How else can you explain his willingness to risk life and limb to shoot in such forbidding places as the Amazonian rain forest or Antarctica? In perhaps his greatest film, Fitzcarraldo -- which is about a dreamer who hatches a scheme to drag a riverboat over a mountain -- Herzog decides, for the purposes of realism, to actually drag a boat over a mountain. No special effects. No studios. In the middle of the Peruvian jungle. The production, perhaps the most miserable in the history of film, is the subject of the documentary The Burden of Dreams. After six punishing months, a weary-looking Herzog described his surroundings:

His worldview brims with a heroic pessimism that is pulled straight out of the German Romantic poets. Nature is not some harmonious anthropomorphized playground. It is instead nothing but “chaos, hostility and murder.” For those sick of the cynical dishonesty of Hollywood’s current crop of Award-ready fare (hello, The Imitation Game), Herzog comes as a bracing tonic. An icon of what independent cinema should be rather than what it has largely become. Below is Herzog’s list of advice for filmmakers, found on the back of his latest book Werner Herzog – A Guide for the Perplexed. (Hat tip goes to Jason Kottke for bringing it to our attention.) Some maxims are pretty specific to the world of moviemaking – “That roll of unexposed celluloid you have in your hand might be the last in existence, so do something impressive with it.” Other points are just plain good lessons for life -- “Always take the initiative,” “Learn to live with your mistakes.” Read along and you can almost hear Herzog’s malevolent Teutonic lilt.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in January 2015. Related Content: Portrait Werner Herzog: The Director’s Autobiographical Short Film from 1986 Werner Herzog Picks His 5 Top Films Werner Herzog and Cormac McCarthy Talk Science and Culture Werner Herzog’s Eye-Opening New Film Reveals the Dangers of Texting While Driving Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here. Werner Herzog Offers 24 Pieces of Filmmaking and Life Advice is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

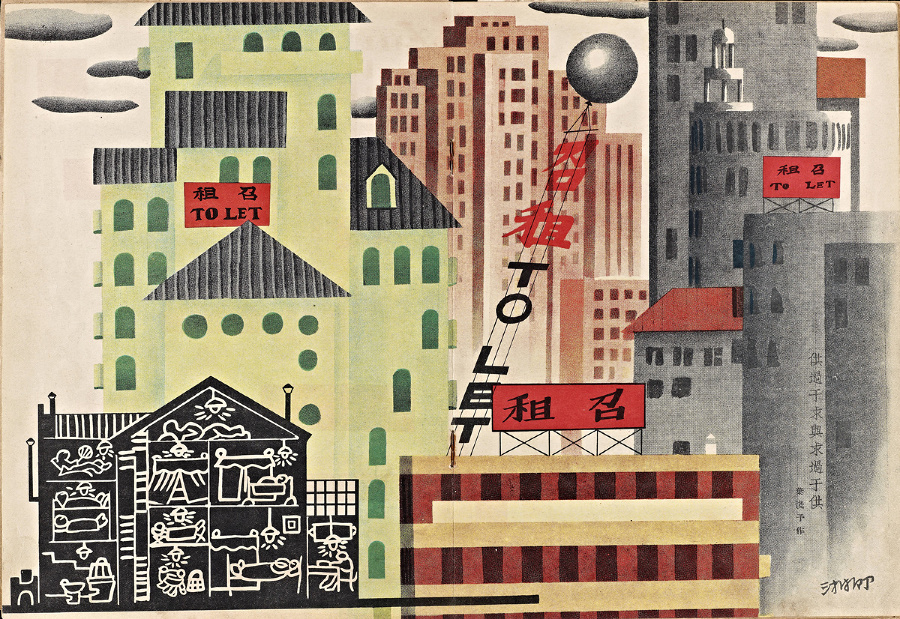

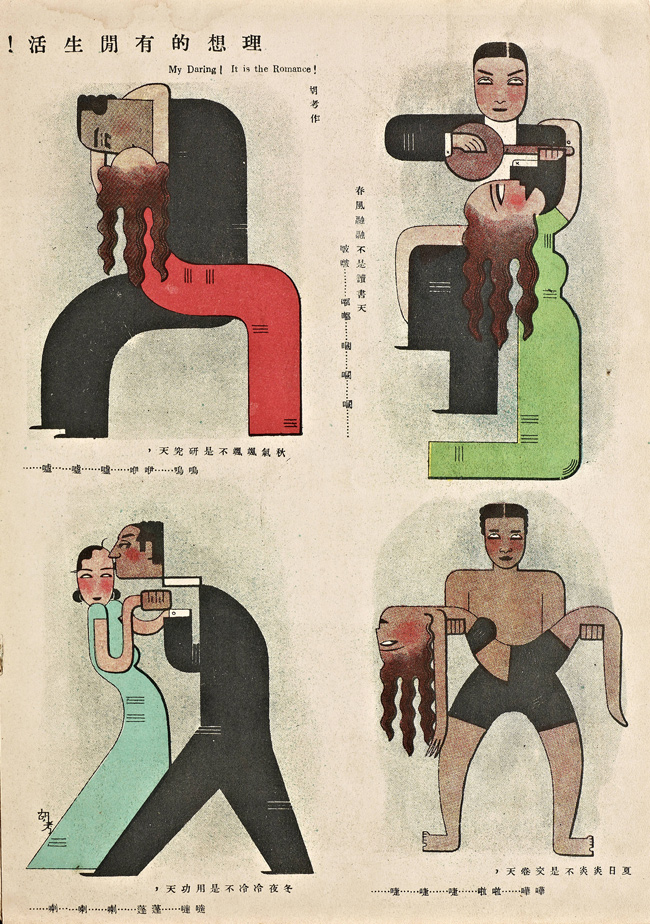

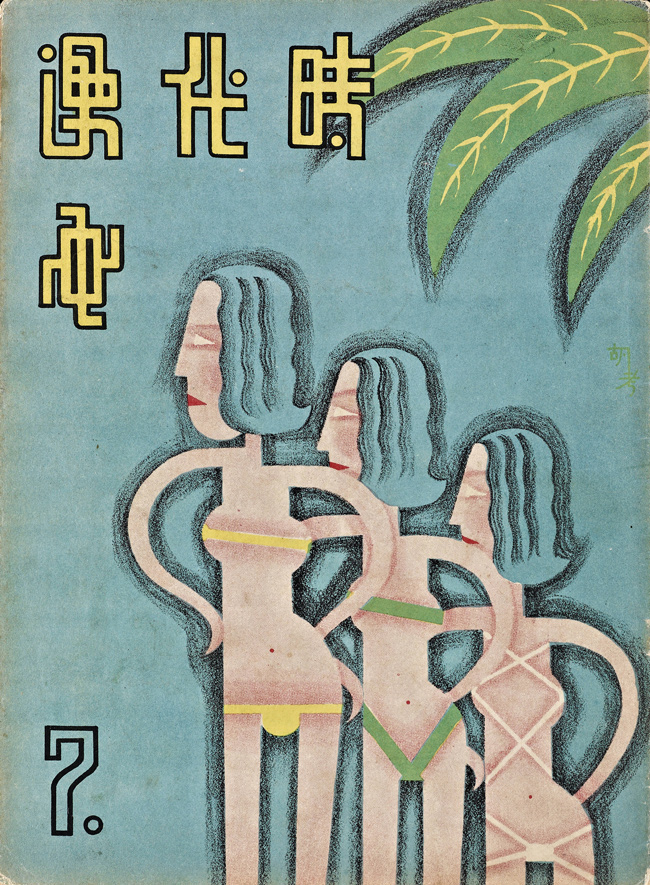

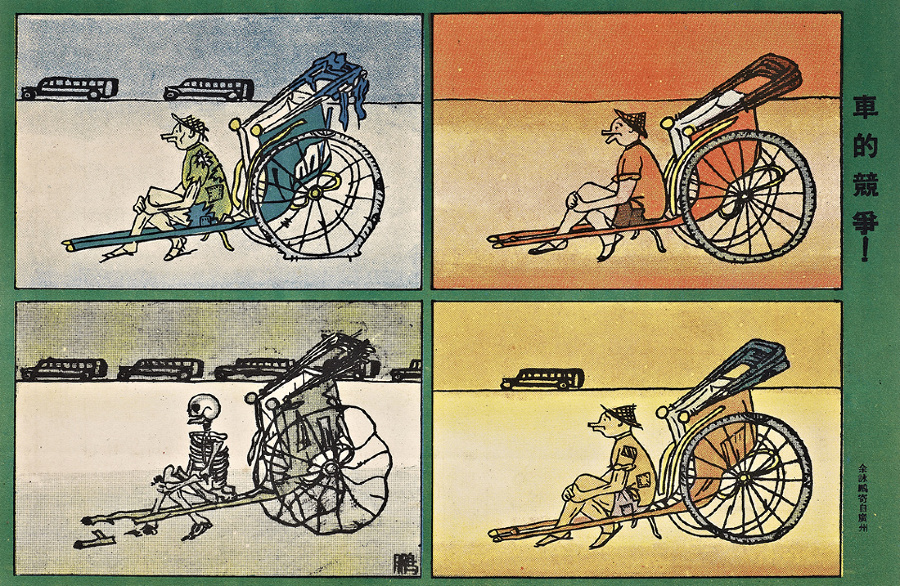

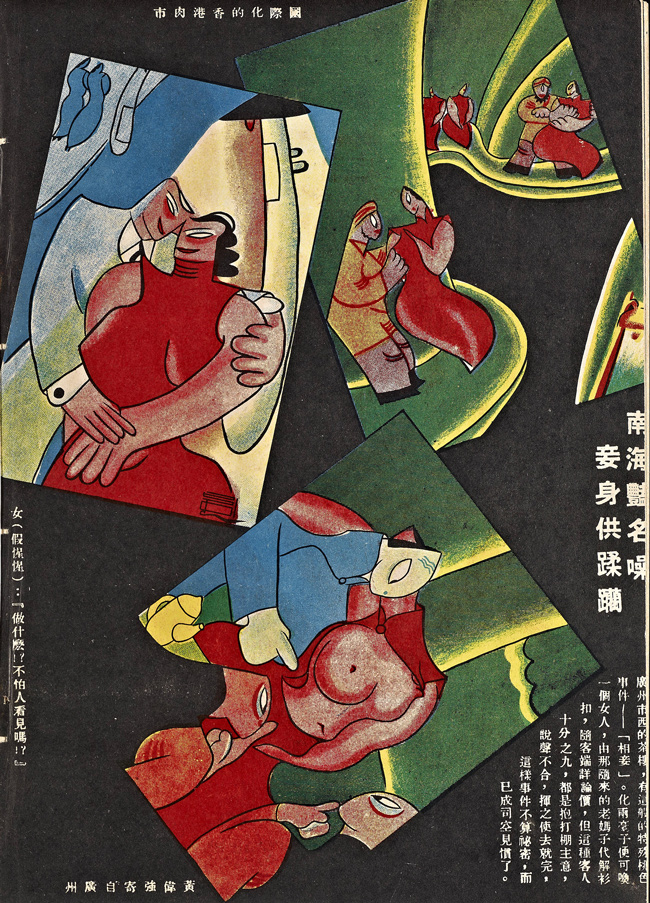

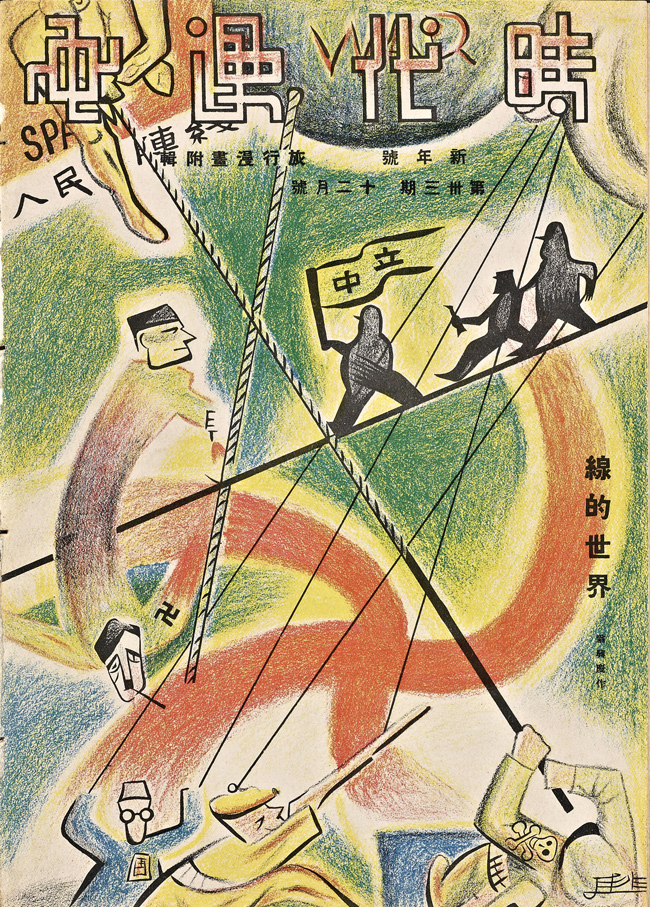

| 2:00p | The Provocative Art of Modern Sketch, the Magazine That Captured the Cultural Explosion of 1930s Shanghai

Such heady days also gave rise to media that reflected and critiqued them, and 1930s Shanghai produced no more compelling an example of such a publication than Modern Sketch (????, Shídài Mànhuà). Among its points of interest, writes Crespi, "one can point to Modern Sketch’s longevity, the quality of its printing, the remarkable eclecticism of its content, and its inclusion of work by young artists who went on to become leaders in China’s 20th-century cultural establishment. But from today’s perspective, most intriguing is the sheer imagistic force with which this magazine captures the crises and contradictions that have defined China’s 20th century as a quintessentially modern era."

Published monthly from January 1934 through June 1937, the magazine first appeared on newsstands just over two decades after the collapse of China’s dynastic system. The modernization-minded May Fourth Movement, nationalist Northern Expedition, and purge of communists by “Generalissimo” Chiang Kai-shek were even more recent memories. But the relative stability of the "Nanjing Decade" had begun in 1927, and its zeitgeist turned out to be rich soil for a wild cultural flowering in China's coastal cities, none wilder than in Shanghai. To the reading public of this time Modern Sketch offered treatments of material like "eroticized women, foreign aggression — particularly the rise of fascism in Europe and militarized Japan — domestic politics and exploitation, and modernity-at-large," writes Crespi.

The magazine's attitude "could be incisive, bitter, shocking, and cynical. At the very same time it could be elegant, salacious, and preposterous. Its messages might be as simple as child’s play, or cryptically encoded for cultural sophisticates."

Sometimes it didn't encode its messages cryptically enough: as a result of one unflattering depiction of Xu Shiying, China's ambassador to Japan, the authorities suspended publication and detained editor Lu Shaofei. Not that Lu didn't know what he was getting into with Modern Sketch: "On all sides a tense era surrounds us," he wrote in the magazine's inaugural issue. "As it is for the individual, so it is for our country and the world."

As for an answer to the question of whether the strange and tense but enormously fruitful cultural and political moment in which Lu and his collaborators found themselves wold last, "the more one fails to find it, the more that desire grows. Our stance, our single responsibility, then, is to strive!"

You can read more about what project entailed, and see in greater detail its textual and visual results, in Crespi's history of this magazine that strove to capture the everyday reality of life on display in 1930s Shanghai — "though I sometimes wonder," Ballard writes, "if everyday reality was the one element missing from the city."

via 50 Watts Related content: China’s New Luminous White Library: A Striking Visual Introduction Vintage 1930s Japanese Posters Artistically Market the Wonders of Travel A Curated Collection of Vintage Japanese Magazine Covers (1913-46) Extensive Archive of Avant-Garde & Modernist Magazines (1890-1939) Now Available Online Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The Provocative Art of Modern Sketch, the Magazine That Captured the Cultural Explosion of 1930s Shanghai is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

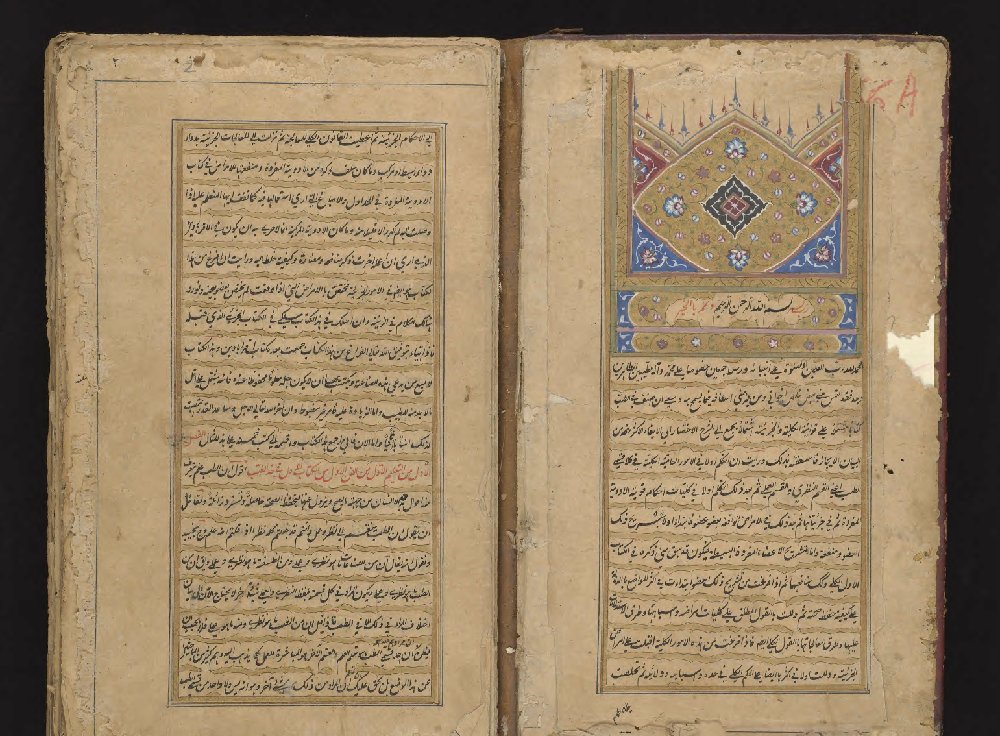

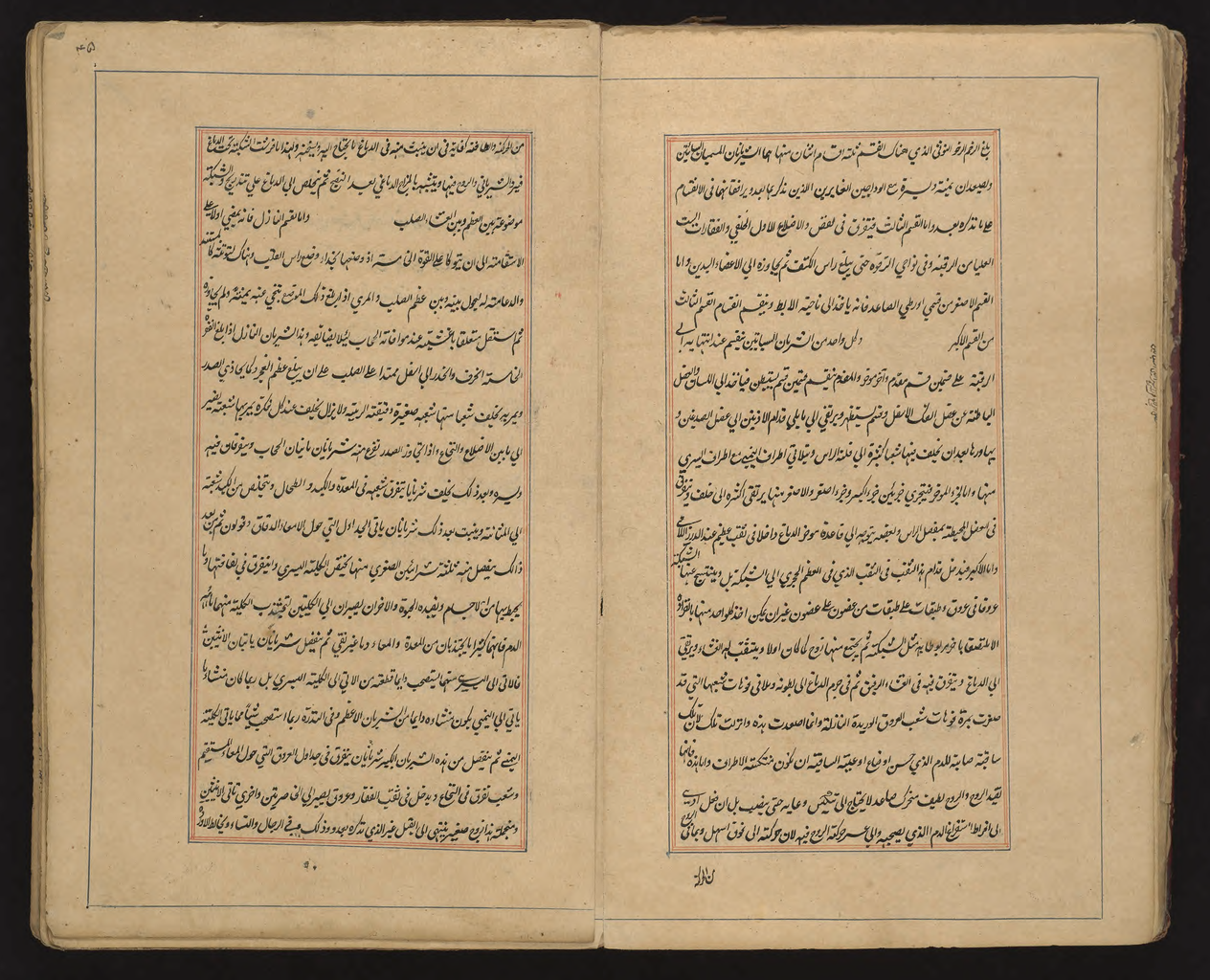

| 5:47p | Discover the Persian 11th Century Canon of Medicine, “The Most Famous Medical Textbook Ever Written”

It may never lend a catchy title to a steamy TV hospital drama, but Avicenna’s 11th-century Canon of Medicine has the distinction of being “the most famous medical textbook ever written.” It has remained, as William Osler wrote in a 1918 Yale lecture, “a medical bible for a longer time than any other work.” Completed in 1025, the compendium drew Greek, Roman, Arabic, Indian, and Chinese medical science together in five dense volumes of material informed by the theories of Galen and structured by the systematic philosophy of Aristotle, whom Avicenna (Ab?-?Al? al-?usayn ibn-?Abdall?h Ibn-S?n?) called “The First Teacher.” Translated into Latin in the 12th century and “often revised,” the Canon, notes the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, “formed the basis of medical instruction in European Universities until the 17th century.” A copy of excerpts from the text has even been found translated into 15th-century Irish, demonstrating a link between medieval Ireland and the Islamic world. Avicenna’s influence generally on the intellectual culture of medieval and early modern Europe and the Arab-speaking world can hardly be overstated. Born in 980 A.D., the Persian philosopher and physician was instrumental in the recovery of Hellenic thought, first in the Islamic world, then later in Europe. He took to the study of medicine very early in his extraordinary career. “I became proficient in it in the shortest time,” he says, “until the excellent scholars of medicine began to study under me.” He also became a practicing physician, inspired by a desire to put his learning to the test. “Through my experiences I acquired an amazing practical knowledge and ability in methods of treatment.” The practical knowledge in The Canon of Medicine was largely the basis for its continued use for centuries. It lays out rules for drug testing, which include an insistence on human trials and the importance of conducting multiple experiments and showing consistent results across cases. Like most classical scientific texts, it weaves empirical observation with metaphysics, theology, scholastic speculation, and cultural biases particular to its time and place. But the practical outlines of its medical knowledge transcend its archaisms. The work presents “an integrated view of surgery and medicine,” notes the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. In addition to his imminently useful guide for assessing the effects of drugs, Ibn Sina tells his readers “how to judge the margin of healthy tissue to remove with an amputation,” an intervention that has saved countless numbers of lives. “The enduring respect in the 21st century for a book written a millennium earlier is testimony to Ibn Sina’s achievement.”

One of the defining features of the text is its insistence on the practice of medicine as a systematic scientific pursuit of equal merit to the theorizing of it:

Of course, much of the medical theory in the Canon has been disproven, but it remains of keen interest to students of the history of medicine and of European and Islamic intellectual cultural history more generally. Avicenna towers above his contemporaries, yet his work also bears witness to the larger “intellectual climate of his time,” as the site Medical History Tour points out. He emerged from a milieu “shaped by centuries of translation and cross-cultural scholarship” of Greek, Roman, Indian, Chinese, Persian, and Arabic literature. “A rich Persian medical tradition began 200 years before Avicenna.” Nonetheless, “however the world came by the genius of Avicenna, his influence was lasting,” with The Canon of Medicine remaining a definitive “best practices” guide to medicine for centuries after its composition. See full scans of several Arabic copies of the text at the Library of Congress’s World Digital Library and read a full English translation of the massive 5-volume work, with its extensive chapters on definitions, anatomy, etiology, and treatments, at the Internet Archive. Related Content: 1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online 700 Years of Persian Manuscripts Now Digitized and Available Online How Arabic Translators Helped Preserve Greek Philosophy … and the Classical Tradition Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Discover the Persian 11th Century Canon of Medicine, “The Most Famous Medical Textbook Ever Written” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/10/24 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |