[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, November 7th, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 9:00a | When White Supremacists Overthrew a Government (1898): The Hidden History of an American Coup White supremacist ideology has found a home in both major political parties at different times in the country’s history. But it has not always been openly acknowledged, receding into coded language and whispers when out of political favor. In the decades after Reconstruction and after World War I, however, politicians shouted racist, xenophobic speeches through bullhorns, inciting thousands of lynchings across the country. One incredibly bloody mass killing, the so-called Tulsa “Race Riot” of 1921—actually a massacre and decimation of a thriving business district—has come back into public consciousness after a fictionalized depiction on HBO’s Watchmen series. Twelve years earlier, another definitive event took place in Wilmington, North Carolina. If mentioned at all, it’s been glossed over quickly in textbooks and the town’s historical memory, but the Wilmington Massacre is part of a history of racial terrorism many celebrated openly, then sought to suppress, deny, and ignore when it became embarrassing. Yale professor of history Glenda Gilmore calls the period a “50-year black hole of information." Growing up in North Carolina herself, she says, “I had never heard the word ‘lynching’ until I was 21.” In fact, as the Vox video above notes, librarians in Wilmington refused even to release materials related to the massacre. This is odd considering its significance to American history as the only successful violent overthrow of an elected U.S. government on U.S. soil. It was a coup (despite the way that word has been deliberately misused) involving no due process or constitutional checks and balances. The violence began on the morning of November 10, 1898, when the offices of The Daily Record were set on fire. By the day’s end, “as many as 60 people had been murdered, and the local government that was elected two days prior had been overthrown and replaced by white supremacists,” writes The Atlantic. This was no spontaneous riot. The events had been planned and promoted by the most prominent leaders in the city and state, who gathered at the Thalian Hall opera house in Wilmington the previous month to hear a speech in which Democratic Congressman Alfred Waddell declared “We will never surrender to a ragged raffle of Negroes, even if we have to choke the Cape Fear River with carcasses.” This kind of rhetoric was commonplace. White supremacist clubs around the State, goaded on by South Carolina senator Ben Tillman, resounded with talk of “shotgun politics” to oust elected Black Republicans. After Waddell’s Thalian Hall speech, he traveled to Goldsboro for a “White Supremacy Convention” attended by 8,000 people. There, Major William Guthrie promised, “Resist our march of progress and civilization and we will wipe you off the face of the earth.” The convention was hailed in The Fayetteville Observer as “A White Man’s Day." and Tillman’s exhortation “in behalf of the restoration of white rule” by violence was called “a great speech for democracy.” The massacre and overthrow of Wilmington's government followed soon after. Historians were able to reconstruct the events after their suppression in part because they were so widely celebrated for decades afterward. “In the 1910s, 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, they bragged about it,” says historian David S. Cecelski. Along with a disturbing resurgence, we've also recently seen a public reckoning with the racial terror and tyranny of the late-19th and early 20th centuries, as the memory of lynching is enshrined in memorials and museums, and stories buried since the 50s are unearthed. This history has been also been used by some modern-day Republicans to grind political axes against modern-day Democrats, as though the major 1960s Civil Rights realignment never happened. Shallow partisanship aside, the fact remains: what the Wilmington insurrectionists and their allies and inciters campaigned, burned, and killed for was a return to the oppressive rule of an elite white minority, against a multiracial democratic coalition that had united former slaves and poor white farmers in a fusion government representing working people in North Carolina and the thriving, majority Black population in Wilmington, its largest city at the time. Learn more about the history of the Wilmington Massacre in the Vox video above and in the excellent collection Democracy Betrayed. Related Content: New Interactive Map Visualizes the Chilling History of Lynching in the U.S. (1835-1964) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness When White Supremacists Overthrew a Government (1898): The Hidden History of an American Coup is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 12:00p | The Digital Dada Library: Discover the Archive That Preserves the Original Publications of the Experimental Anti-Art Movement Online

Critical theorists like Theodor Adorno may have overreached in claiming that all mass culture is mediocre, mechanized propaganda made to justify the status quo. But that doesn’t mean they were entirely wrong. Over and over we see even the most subversive art, literature, film, and music has a way of being tamed and Bowdlerized. Global mega-culture industries don’t need to censor what they don’t like; they only need to buy it, rebrand it, or price it out of reach. So what? Why do we need challenging, independent art when we have endless entertainment? Is the concept a nostalgic, elitist, Eurocentric idea? Artists have justified the need for art since antiquity, with poetic and logical arguments of every kind. But Dada artists of the early 20th century broke ranks, building their movement on the insight that no defense could possibly mean anything when it came to art’s purpose, especially in the face of the technocratic slaughter of World War I.

When the hyperrationalism of modernity led to mass death and destruction, the only humane response was to declare war on rationalization—to “destroy the hoaxes of reason,” as French artist Jean Arp put it. “For the disillusioned artists of the Dada movement,” the Museum of Modern Art explains, “the war merely confirmed the degradation of social structures that led to such violence: corrupt and nationalist politics, repressive social values, and unquestioning conformity of culture and thought.” Dada took a combative stance against, for one thing, the insistence that art justify its existence to win establishment approval. “All activity is vain,” declared poet Tristan Tzara in his 1918 “Dada Manifesto,” including the “monetary system, pharmaceutical product, or a bare leg advertising the ardent sterile spring…. The beginnings of Dada were not the beginnings of art, but of disgust” with the ossified culture of the “nice, nice bourgeois,” who would preserve at any cost “the possibility of wallowing in cushions and good things to eat.”

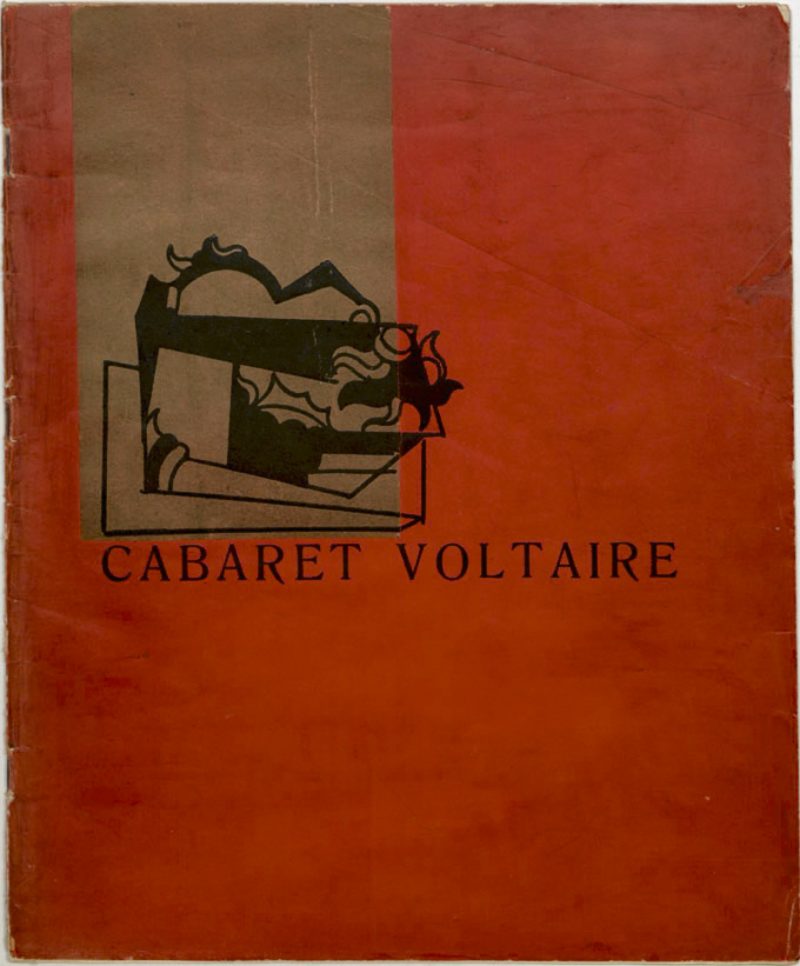

“And so Dada,” wrote Tzara, “was born of a need for independence, of a distrust toward unity.” Such declarations aside, the movement was decidedly unified in its aims. “For us, art is not an end in itself," poet Hugo Ball wrote. “It is an opportunity for the true perception and criticism of the times we live in.” This critique required new experimental techniques that deformed and repurposed the technologies of mass culture. The undertaking would not have been possible without a Dada publishing wing that turned out scores of journals, magazines, books, leaflets, essays, manifestos, etc., written, designed, edited, illustrated, photographed, and controlled by the artists themselves. They might find no small amount of irony in the fact that their productions have received the ultimate institutional sanction: housed in “nice, nice bourgeois” museums, libraries, and universities around the world.

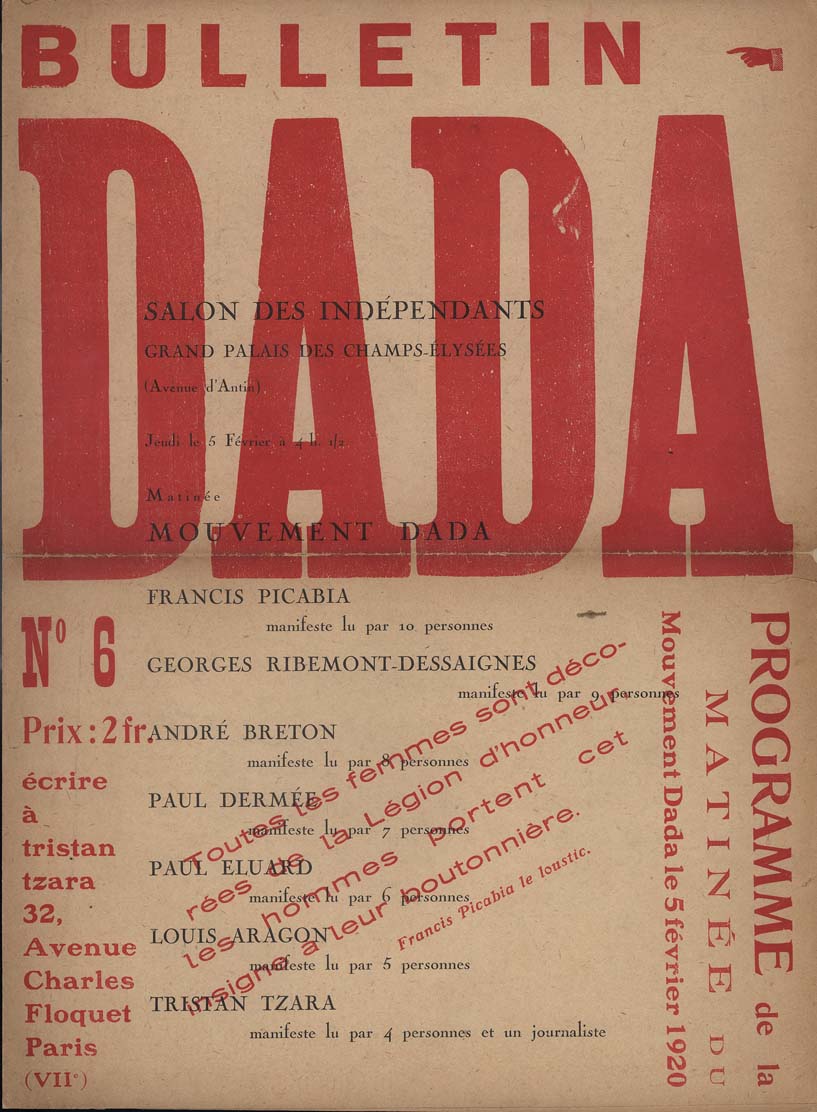

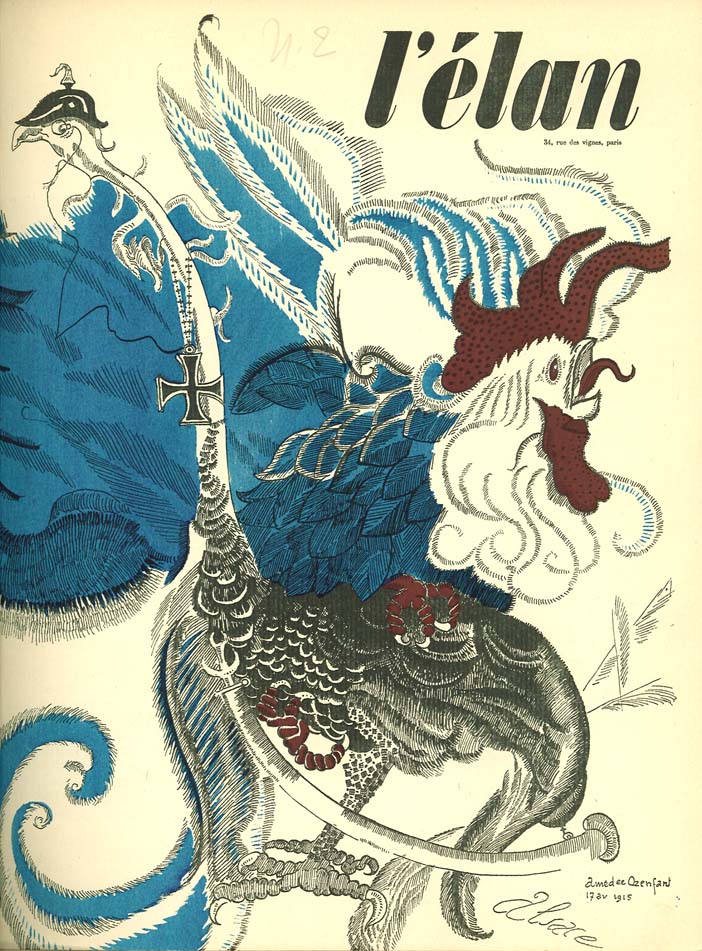

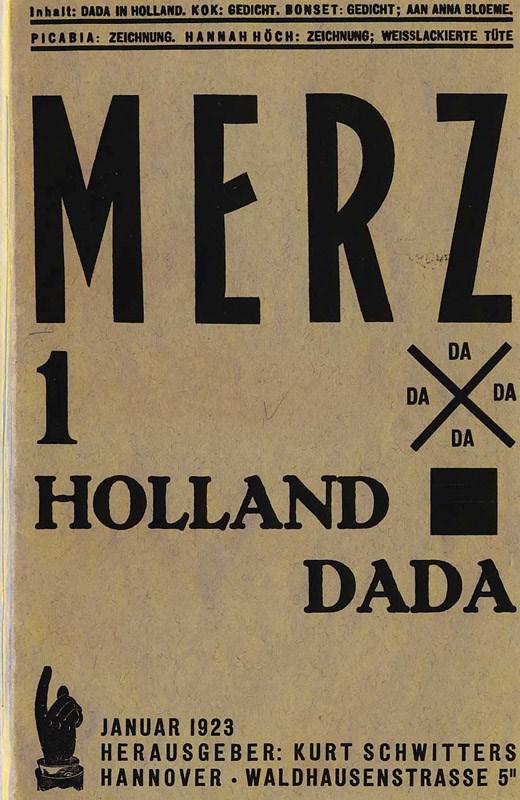

The University of Iowa’s International Dada Archive has amassed a considerable number of Dada publications and offers a wealth of high-quality scanned images of the originals on their site. “The first section” of their Digital Library “includes some of the major periodicals of the Dada movement from Zurich, Berlin, Paris, and elsewhere.” These are not always complete runs, though the library has included “reprints of issues for which we do not own originals” to make up for missing items in the collection. The second section of the site “includes books by some of the participants in the Dada movement, as well as some of the more ephemeral Dada-era publications, such as exhibiton catalogs and broadsides.” You’ll find writings by all of the artists mentioned above, as well as other well-known names like Max Ernst, Paul Eluard, George Grosz, Man Ray, Francis Picabia, and more.

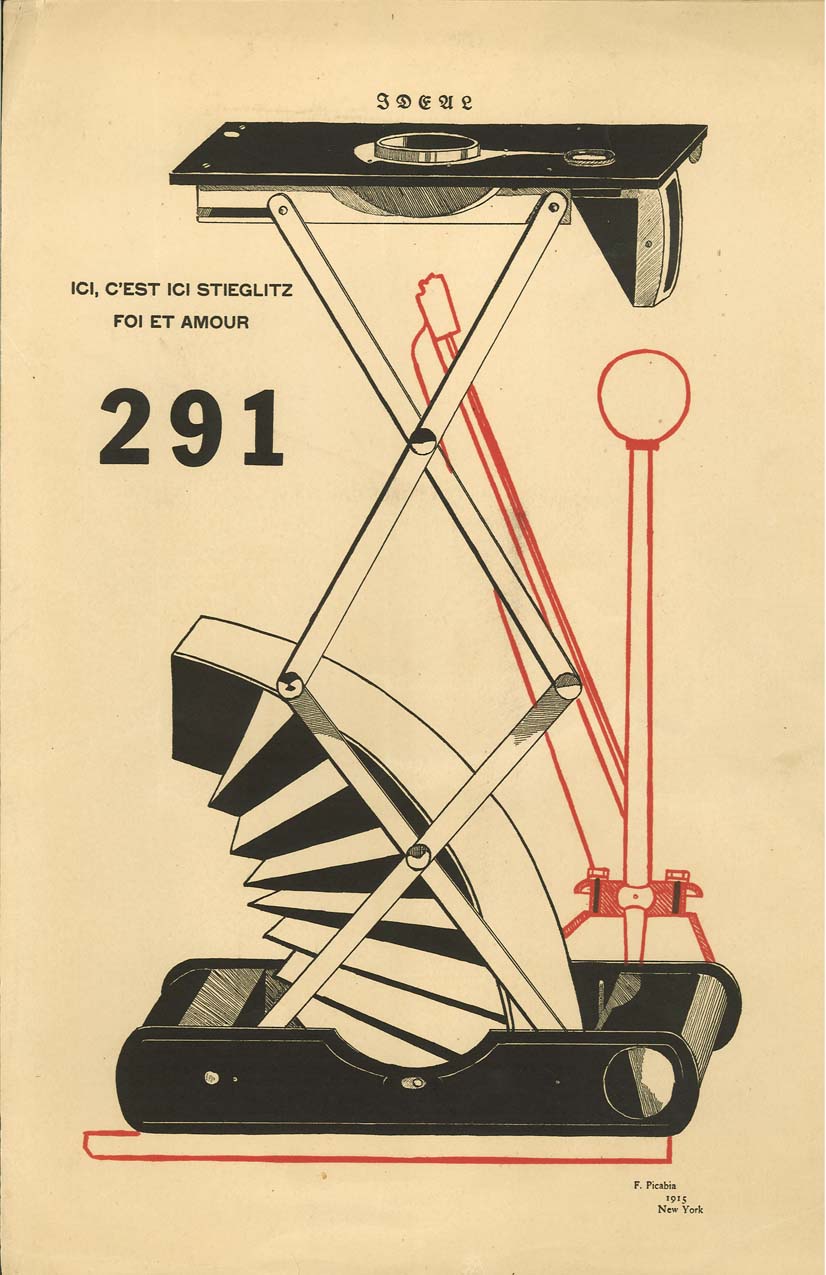

All of these publications are, of course, in their original European languages, though you can find translations of many documents online. The most influential Dada magazine in English, Alfred Stieglitz’s 291, will give monolingual readers a flavor of the larger scene. Published in New York between 1915 and 1916, the short-lived journal included many of the major European names. Its first issue covered experiments like “simultanism,” “sincerism,” and “idiotism,” and introduced visual poetry to American readers. Issue 5-6 featured on its cover one of the weird, nonsensical machines of Francis Picabia. Dada splintered into other movements before its artists were forced out of Europe or hounded into obscurity by the Nazis. Their unified attempt to fragment and disrupt the dominance of mass culture was itself fragmented and disrupted by a horrific new war machine. But while their ideas may have been co-opted, their spirit may yet live on. Inspired by their work, perhaps a new generation will take up the Sisyphean task of making radical, critical, experimental art to subvert the homogenizing juggernaut of the culture industry. Enter the University of Iowa's Digital Dada Library here. Related Content: Hear the Experimental Music of the Dada Movement: Avant-Garde Sounds from a Century Ago Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Digital Dada Library: Discover the Archive That Preserves the Original Publications of the Experimental Anti-Art Movement Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:21p | The Benefits of Boredom: How to Stop Distracting Yourself and Get Creative Ideas Again Here in the 21st century, we have conquered boredom. Impressive though that achievement may be, it hasn't come without cost: As with many other conditions we've managed to eliminate from our lives, boredom now looks to have been essential to full human existence. Has our reality of on-demand distractions, tailored ever more closely to our impulses and desires, robbed us of yet another form of everyday adversity that built up the character of previous generations? Perhaps, but more importantly, it may also have dried up our well of creativity. The frustration that descends on us when trying to come up with new ideas; the itch we feel, whenever we start doing something, to do something else; our inability to go more than a few minutes without looking at our phones: we can hardly assume these modern problems are unrelated. "When you're bored, you tend to daydream, and your mind wanders, and this is a very, very important part of the creative process," says psychologist Sandi Mann in the animated BBC REEL video at the top of the post. "If you find that you're stuck on a problem, or you're really worried about something and can't seem to find a way out, take some time out. Just be bored. Let your mind wander, and you might just find that a creative solution will pop into your head." But we've fallen into the habit of "swiping and scrolling our boredom away," seeking "a dopamine hit from new and novel experiences" — most often digital ones — to assuage our fears of boredom. And the more such stimulation we get, the more we need, meaning that, "paradoxically, the way to deal with boredom is to allow more of it into our life." "Once you start daydreaming and allow your mind to really wander," Mann says, "you start thinking a little bit beyond the conscious, a little bit into the subconscious, which allows sort of different connections to take place." She says it in "How Boredom Can Lead to Your Most Brilliant Ideas," a TED Talk by journalist Manoush Zomorodi. Like the public-radio podcaster she is, Zomorodi brings in interview clips from not just Mann but a range of experts on the subject of boredom and distraction, including neuroscientist Daniel Levitin, who warns that "every time you shift your attention from one thing to another, the brain has to engage a neurochemical switch that uses up nutrients in the brain to accomplish that." And so the "multitasking" in which we once prided ourselves amounts to nothing more than "rapidly shifting from one thing to the next, depleting neural resources as you go." We've become like the experiment subjects, described in the Veritasium video above, who were asked to sit alone in an empty room for a few minutes with nothing in front of them but a button that they knew would shock them. In the end, 25 percent of the women and 60 percent of the men chose, unasked, to shock themselves, presumably out of a preference for painful stimulation over no stimulation at all. How much, we have to wonder, does that ultimately differ from the distractions we compulsively seek at every opportunity in the form of social media, games, and other addictive apps? And what do these increasingly frequent self-administered jolts do to our ability to identify promising avenues of thought and follow them all the way to their most fruitful conclusions? As the old saying goes, only the boring are bored. But if our technological lives keep going the way they've been going, soon only the bored will be interesting. Related Content: How to Take Advantage of Boredom, the Secret Ingredient of Creativity How Information Overload Robs Us of Our Creativity: What the Scientific Research Shows How to Focus: Five Talks Reveal the Secrets of Concentration Why Time Seems to Speed Up as We Get Older: What the Research Says Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. The Benefits of Boredom: How to Stop Distracting Yourself and Get Creative Ideas Again is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/11/07 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |