[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, December 3rd, 2019

| Time | Event |

| 9:00a | How Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Helps Us Understand the Meaning of Life Abraham Maslow’s 1943 paper “A Theory of Human Motivation” was “written as pure psychology,” notes the BBC, but “it has found its main application in management theory.” It has also become one of the best-known theories of human well-being. But whether you first encountered it in an Intro Psych class or a business training seminar, you’ll immediately recognize the triangular scheme of the “hierarchy of needs,” leading upward from basic physical necessities to full self-actualization. Maslow’s theory had great explanatory power, offering what he called a “third force" between idealism and materialism. He was in line, he wrote, with the more spiritually-minded pragmatists, or what he called “the functionalist tradition of James and Dewey… fused with the holism of Wertheimer, Goldstein, and Gestalt Psychology, and with the dynamicism of Freud and Adler.” Against the general trend in psychology to pathologize, Maslow offered his paper as “an attempt to formulate a positive theory of motivation.” His work helped inspire managers to “shape the conditions that create people’s aspirations,” says Gerald Hodgkinson, psychologist at the Warwick Business School,” in order to influence productivity and loyalty in their employees. If this seems manipulative, perhaps Maslow can be held no more responsible than can Freud for the use of his work by his nephew Edward Bernays, who almost single-handedly invented modern advertising and propaganda using Freudian appeals. Maslow had in mind something grander than managing human capital—"no less,” says Alain de Botton in the School of Life video above, "than the meaning of life.” His quest came itself from a personal motivation. “I was awfully curious,” he once remarked, “to find out why I didn’t go insane.” Or, as de Botton says, he wanted to know “what could make life purposeful for people, himself included, in modern-day America, a country where the pursuit of money and fame seemed to have eclipsed any more interior or authentic aspirations.” De Botton walks us through the hierarchy, which divides into two dimensions, the material—basic biological needs (including sex) and the need for safety—and the psychological. In this last category, we find the social needs for belonging (“the love needs,” Maslow called them) and esteem, capped with the apex need—self-actualization—the realization of one’s true purpose. “A musician must make music,” wrote Maslow, “an artist must paint, a poet must write, if he is to be ultimately happy. What a man can be, he must be." “How do we arrange our priorities and give due regard to the different and competing claims we have on our attention?” De Botton asks. In an increasingly disembodied culture, we may ignore or neglect the needs of the body, even if we have the means to meet them, an unsustainable course over the long term. Even those on the path of the “starving artist” will sadly have to reevaluate after a time, Maslow argued, giving priority to their need to eat over their creative aspirations. But Maslow’s is not, or not only, a theory of rational choice. On the contrary, he had a compassionate response to alienation and poverty of all kinds: “the bold postulation,” he wrote “that a man who is thwarted in any of his basic needs may fairly be envisaged simply as a sick man…. Who is to say that a lack of love is less important than a lack of vitamins?” The material needs in Maslow’s scheme must be consistently met in order to create a stable base for all the others. Yet, while self-actualization may sit at the top, its lack, according to Maslow, may still affect us as much as much if we suffered from “pellagra or scurvy." It’s possible to read in the hierarchy of needs a psychological elaboration of Marx’s slogan “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs,” but Maslow was no dialectical materialist. He valued spirituality, and if he was “ambivalent about business,” he also held out hope that companies would market products to meet consumers’ higher desires as well as their needs for food, shelter, and physical comfort. Maslow died in 1970, and in the ensuing decades, his wish has become a hugely profitable reality. From religious broadcasting companies to social media to dating and meditation apps, marketers find ever-new ways to sell promises of belonging, esteem, and self-actualization. Perhaps Maslow would see this as progress. In any case, commerce aside, his theory continues to address pressing sociological and existential problems. And as an aid to personal reflection, it can help us notice how we “haven’t arranged and balanced our needs as wisely and elegantly as we might,” says de Botton. We may have denied ourselves, or been denied, important experiences we need in order to become who we truly are. Related Content: The Causes & Prevalence of Suicide Explained by Two Videos from Alain de Botton’s School of Life The Neuroscience & Psychology of Procrastination, and How to Overcome It Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Helps Us Understand the Meaning of Life is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

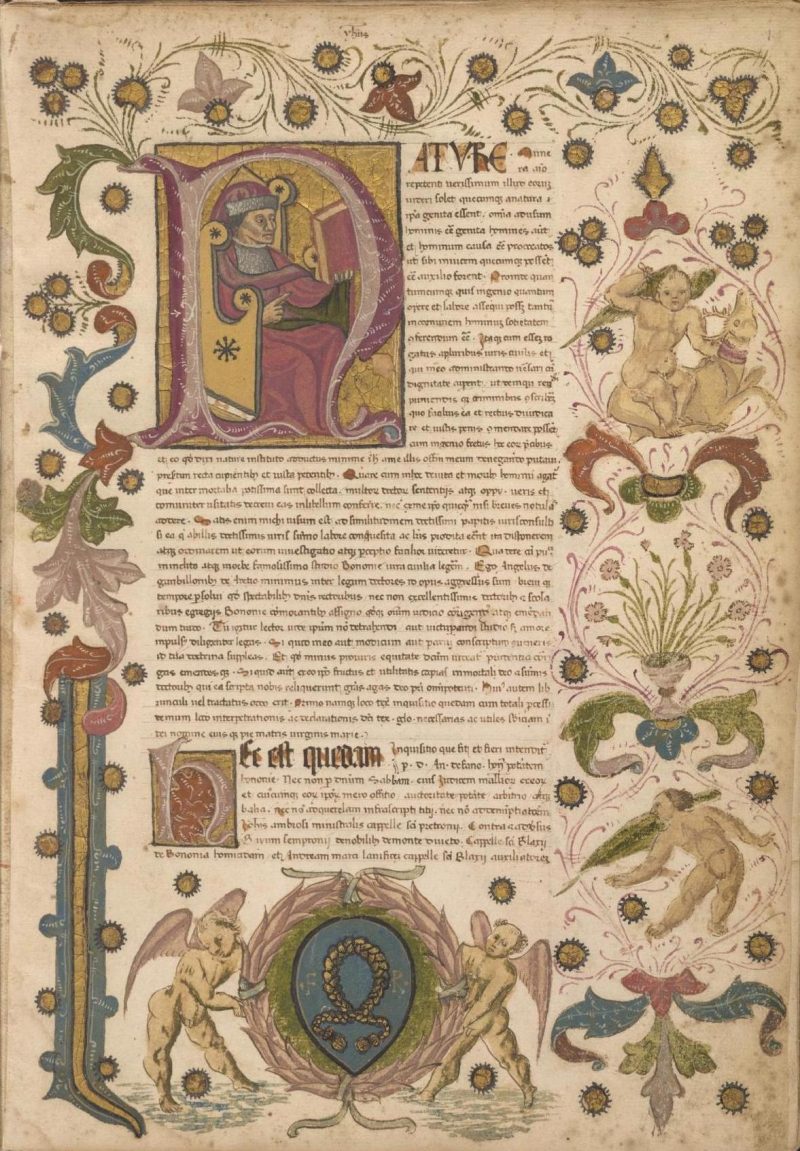

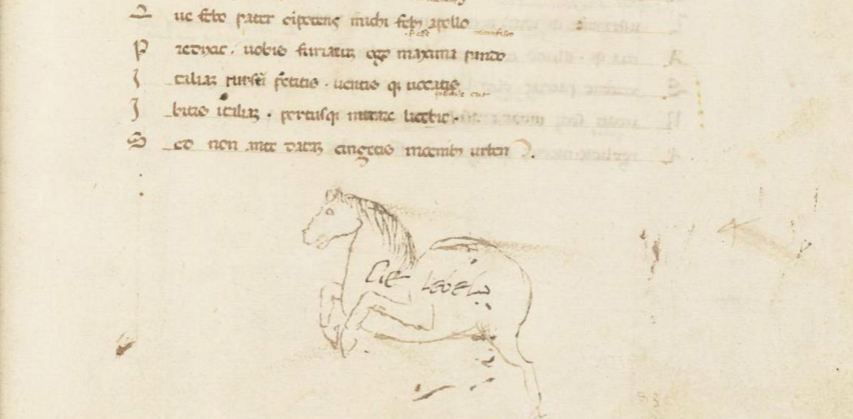

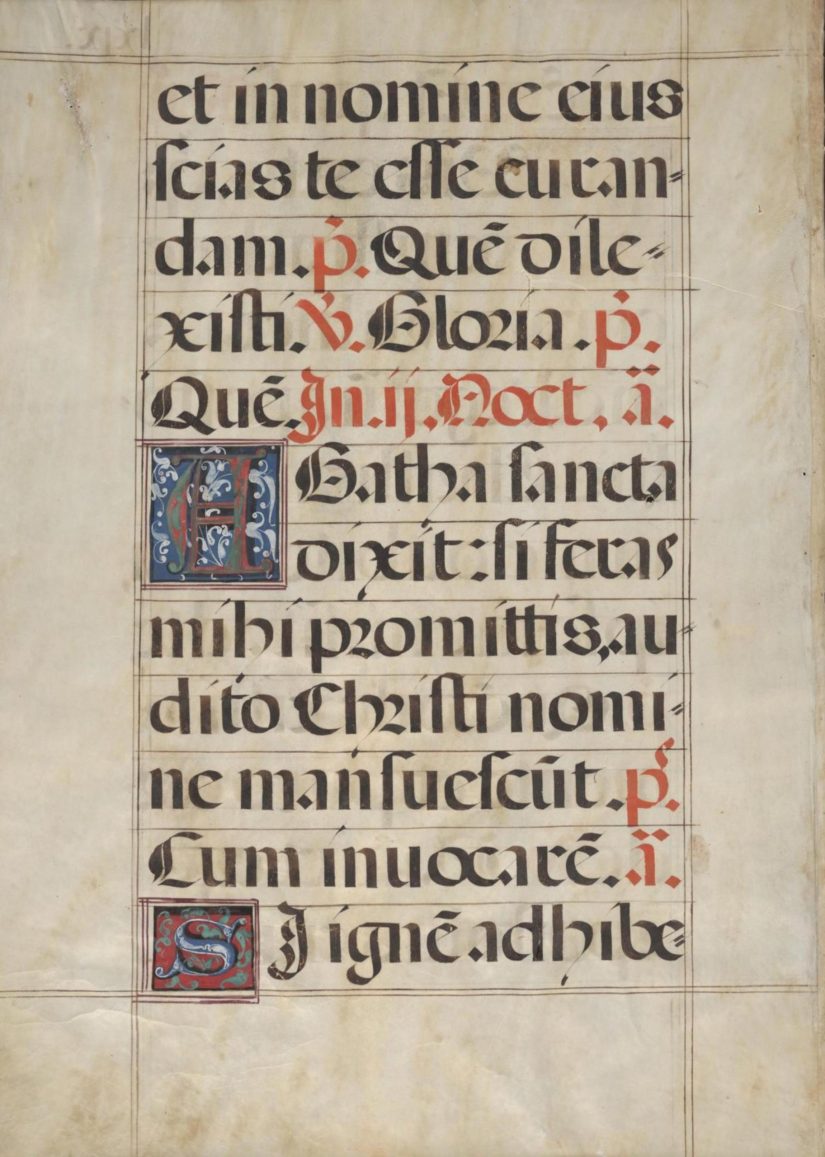

| 12:00p | 160,000 Pages of Glorious Medieval Manuscripts Digitized: Visit the Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis

We might think we have a general grasp of the period in European history immortalized in theme restaurant form as "Medieval Times." After all, writes Amy White at Medievalists.net, “from tattoos to video games to Game of Thrones, medieval iconography has long inspired fascination, imitation and veneration.” The market for swordplay, armor, quests, and sorcery has never been so crowded. But whether the historical period we call medieval (a word derived from medium aevum, or “middle age”) resembled the modern interpretations it inspired presents us with another question entirely—a question independent and professional scholars can now answer with free, easy reference to “high-resolution images of more than 160,000 pages of European medieval and early modern codices”: richly illuminated (and amateurishly illustrated) manuscripts, musical scores, cookbooks, and much more.

The online project, called Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis, houses its digital collection at the Internet Archive and represents “virtually all of the holdings of PACSCL [Philadelphia Area Consortium of Special Collections Libraries]," a wealth of documents from Princeton, Bryn Mawr, Villanova, Swarthmore, and many more college and university libraries, as well as the American Philosophical Society, National Archives at Philadelphia, and other august institutions of higher learning and conservation. Lehigh University “contributed 27 manuscripts amounting to about 5,000 pages,” writes White, including “a 1462 handwritten copy of Virgil’s Aeneid with penciled sketches in the margins" (see above). There are manuscripts from that period like the Italian Tractatus de maleficiis (Treatise on evil deeds), a legal compendium from 1460 with “thirty-one marginal drawings in ink” showing “various crimes (both deliberate and accidental) being committed, from sword-fights and murders to hunting accidents and a hanging.”

The Tractatus' drawings “do not appear to be the work of a professional artist,” the notes point out, though it also contains pages, like the image at the top, showing a trained illuminator's hand. The Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis archive includes 15th and 16th-century recipes and extracts on alchemy, medical texts, and copious Bibles and books of prayer and devotion. There is a 1425 edition of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in Middle English (lacking the prologue and several tales). These may all seem of recent vintage, relatively speaking, for a medieval archive, but the collection reaches back to the 9th century, with hundreds of documents, like the 1000 AD music manuscript above, from a far earlier time. "Users can view, download and compare manuscripts in nearly microscopic detail," notes White. "It is the nation’s largest regional online collection of medieval manuscripts," a collection scholars can draw on for centuries to come to learn what life was really like—at least for the few who could read and write—in Medieval Times. via Medievalists.net Related Content: Why Knights Fought Snails in Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts The Medieval Masterpiece, the Book of Kells, Is Now Digitized & Put Online A Free Yale Course on Medieval History: 700 Years in 22 Lectures Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness 160,000 Pages of Glorious Medieval Manuscripts Digitized: Visit the Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | Punk Dulcimer: The Ramones’ “I Wanna Be Sedated” Played on the Dulcimer Sam Edelston can rock the duclimer. On his YouTube channel, he writes: "Dulcimers are natural rock instruments. In fact, I even say that dulcimers are among the world's coolest musical instruments, and they deserve to be known by the general public - the way that everybody knows guitars and ukuleles. Though usually associated with old folk songs and tunes, dulcimers are great for a shocking variety of modern music, too. I do these videos to inspire more people to play and listen to dulcimer music, in diverse, non-traditional styles." Above, watch him cover the Ramones' 1978 classic "I Wanna Be Sedated." Find more covers of Zeppelin, the Stones & Beatles here. And yet more covers--including Bowie's "Space Oddity" and Sabbath's "War Pigs"--on the Contemporary Dulcimer YouTube Channel. Enjoy. Would you like to support the mission of Open Culture? Please consider making a donation to our site. It's hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. Also consider following Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and sharing intelligent media with your friends. Or sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. Related Content: Finnish Musicians Play Bluegrass Versions of AC/DC, Iron Maiden & Ronnie James Dio A Bluegrass Version of Metallica’s Heavy Metal Hit, “Enter Sandman” Pakistani Musicians Play Amazing Version of Dave Brubeck’s Jazz Classic, “Take Five” Watch Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Voodoo Chile’ Performed on a Gayageum, a Traditional Korean Instrument Punk Dulcimer: The Ramones’ “I Wanna Be Sedated” Played on the Dulcimer is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:30p | Clive James & Jonathan Miller (Both RIP) Talk Together About How the Brain Works "Were they the last representatives of a special kind of public intellectual?" asks John Mullen in the Guardian. He writes of Clive James and Jonathan Miller, two figures who exemplified "the polymath as entertainer." The Australian-born James became famous on the back of the television criticism that turned him into a television fixture himself. The combined TV critic and TV host also played the same dual role in the realm of poetry, and as his life and career went on — and his bibliography greatly expanded — it came to seem that there were few forms, traditions, time periods, or languages his cultural omnivorousness didn't reach. Trained as a doctor before he redefined British comedy as a member of Beyond the Fringe, Miller retained his scientific interests, using his fame to write books and present a television show on anatomy, psychology, and language, and much more besides. Since the deaths of both James and Miller were announced last Friday, the outpouring of tributes (most of them lamenting the seeming loss, in our time, of high-profile roles for entertaining polymaths free to move between "high" and "low") has been accompanied by a renewed enthusiasm for both men's considerable bodies of work. Despite having known each other, James and Miller seem never to have explicitly collaborated on anything — except, that is, an episode of Talking in the Library, an early example of what we would now call an interview web series. Produced from 2006 to 2008, the show has James pioneering a form that has now become standard among podcasters: recording the conversations he wanted to have with his friends anyway. In James' case, his friends include the likes of not just Miller but Martin Amis, Ruby Wax, Ian McEwan, Stephen Fry, and Terry Gilliam. With Miller, James spends the half-hour talking science, and specifically neuroscience. Miller, who specialized in neurology while studying medicine (and who counted Oliver Sacks as a close friend since age 12), returned to the subject in the early 1980s for his book and BBC series States of Mind. Not long thereafter he returned at the age of 50 to his medical studies, diving into neuropsychology at McMaster University and becoming a research fellow at the University of Sussex. Though James abandoned his own university studies in psychology by 1960, his curiosity about the workings of the human brain — and how it could produce all the art, literature, film, and indeed television to whose appreciation he dedicated his life — never abandoned him, as evidenced by the eagerness with which he asks questions of his more neuroscientifically savvy friend. "The brain is the most complicated thing in the universe," says Miller, "so complicated, in fact, that by contrast the universe itself it not much more complicated than a cuckoo clock." Fair to say that both Miller and James had the good luck to possess more complicated, or at least more interesting, brains than average — and that it's our good luck to be able to enjoy their work in perpetuity. Related Content: Atheism: A Rough History of Disbelief, with Jonathan Miller The Drinking Party, 1965 Film Adapts Plato’s Symposium to Modern Times Join Clive James on His Classic Television Trips to Paris, LA, Tokyo, Rio, Cairo & Beyond Your Brain on Art: The Emerging Science of Neuroaesthetics Probes What Art Does to Our Brains Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, and the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future? Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Clive James & Jonathan Miller (Both RIP) Talk Together About How the Brain Works is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/12/03 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |