[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, December 11th, 2019

- "A History of Time Travel Fiction" by Jeremy Gordon

- "The 30 Best Time Travel Movies" by Darren Orf

- "Time Travel: Theories, Paradoxes & Possibilities" by Elizabeth Howell

- "Let's Unravel the Time Travel Paradox of Terminator: Dark Fate" by Angela Watercutter

- "Why Are We So Interested In Time Travel?" by Steve Paulson interviewing James Gleick

- "Time Travel Probably Isn't Possible—Why Do We Wish It Were?" by Simon Worrall, again with Gleick

| Time | Event |

| 8:01a | Pretty Much Pop #22 Untangles Time-Travel Scenarios in the Terminator Franchise and Other Media

Time-travel rules in The Terminator franchise are notoriously inconsistent. Is it possible for someone from the future to travel backwards to change events, given the paradox that with a changed future, the traveler wouldn't then have had the problem to try to come back and fix? Neither the closed-loop series of events in the first Terminator film nor the changed (postponed) future in the second make sense, and matters just get worse through the subsequent films. Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt are joined by Brian's brother and co-author Ken Gerber to talk through the various time travel rulesets and plot scenarios (a good starter list is at tvtropes.org), covering Dr. Who, Back to the Future, Looper, Dark (the German TV show), time loop films a la Groundhog Day (Edge of Tomorrow, Happy Death Day), time-travel comedies (Future Man), historical tourism (Mr. Peabody and Sherman), Timecop's "The same matter cannot occupy the same space," using time-travel to sentimentalize (About Time) or clone yourself (see that Brak Show episode about avoiding homework), and freezing time (like in the old Twilight Zone). Some articles we looked at included: You can find the Brian and Ken short stories we talk about at gerberbrothers.net. Listen to them podcast together and read the science fiction stories they publish at constellary.com. The Partially Examined Life podcast episode Mark hosted where the dangers of AI are discussed is #108 with Nick Bostrom. This episode includes bonus discussion that you can only hear by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts or start with the first episode. Pretty Much Pop #22 Untangles Time-Travel Scenarios in the Terminator Franchise and Other Media is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 9:00a | Author Imagines in 1893 the Fashions That Would Appear Over the Next 100 Years

The world of tomorrow, today, has been the promise of so much futurism of the modern industrial age, in times that now seem quaint to us from our digital perches. Today’s self-appointed visionaries can’t seem to imagine life on Earth a hundred years from now. They pour their resources into interplanetary ventures. But even if some contingent of humanity goes on to colonize the solar system and beyond, there will always be a role for fashion, even in the austere environs of deep space. Still, if predicting the future of humanity is a risky proposition, given the number of unpredictable variables at play, predicting future fashions may be even more fraught with peril. Trends don’t come out of nowhere—they draw, self-consciously or otherwise, from the past. But which pasts end up in the latest season’s collections might be anyone’s guess. Unlike technology, in other words, fashion doesn’t appear to follow any sort of linear trajectory from invention to invention.

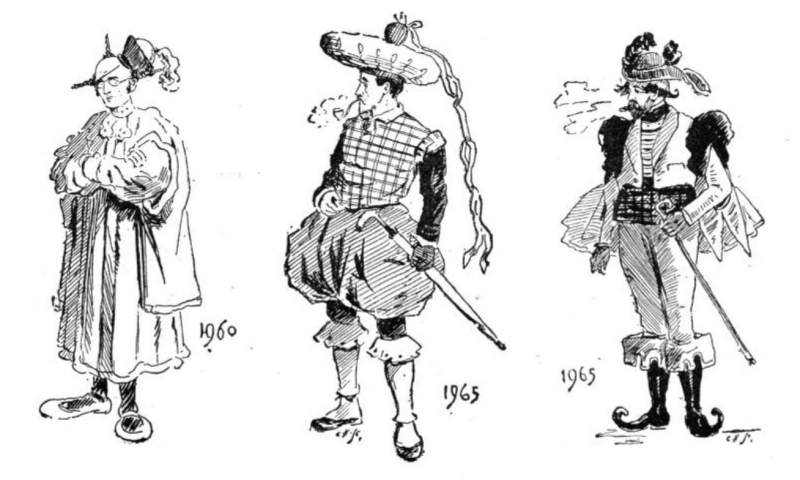

“Fashion,” writes W. Cade-Gall in an 1893 article in the Strand Magazine, “is thought a whim, a sort of shuttlecock for the weak-minded of both sexes to make rise and fall, bound and rebound with the battledore called—social influence.” All of this will be remedied almost fifty years in the future, the author assures their readers. “It will interest a great many people to learn that Fashion assumed the dignity of a science in 1940.” Cade-Gall’s sci-fi satire is not, perhaps, the most serious attempt at predicting future fashions, but it may rank as one of the most amusingly literary. The article, “Future Dictates Fashion" (read online here and at the Internet Archive) purports to describe the contents of a book, discovered by “an elderly gentleman of our acquaintance,” from one hundred years in the future, or 1993, a time, as you can see in the drawing at the top, in which the 18th century has come roaring back, with what appears to be a tricorner hat perched on what appears to be the head of a man smoking a pipe and wearing an ankle-length skirt. Cade-Gall describes the scientific system of fashion in detail, with each historical period acquiring both a “Type” and a “Tendency.”

The period between 1915 and 1940, for example, the last one listed in the future fashion history book’s table, is said to be of the type “Hysterical” and the tendency “Angustorial.” Cade-Gall not only invented the word "angustorial" and this clever story within a story (which turns out to be a dream) but also illustrated the fashions of the imagined 20th century, with the conceit that these are printed plates from the future. Readers familiar with the costume designs of the Bauhaus school might see the 1929 illustrations as somewhat uncanny. Other fashions look like the kind of thing David Bowie might have worn onstage in the early 70s, and some are clearly portmanteaus of different eras and their qualities—from the “bizarre,” “ebullient,” and “hysterical” to the “severe,” “opaque,” and “latorial,” a word, like “angustorial,” that Cade-Gall made up for this occasion. The descriptions of these fashions are as detailed and ridiculous as the illustrations. “Taught by the Darwinian theory” in 1930 we learn, “society discovered whence its tendency to baldness originated. They had recourse by degrees to flexible tiles of extraordinary cut.”

The hairpiece innovation followed some indecision over mens’ pants ten years earlier, which led to a period of knee-breeches. “Trousers, which had been wavering between nautical buttons and gallooned knees—or, in the vernacular of the period, a sail three sheets in the wind—and a flag at half-mast—were the items sacrificed.” It’s all in good fun—more a send-up of the overly-serious meaning attached to clothing than an attempt to look into fashion’s future. But imagining a 20th century dressed the way Cade-Gall imagines it might make us pine for a more ostentatiously (if impractically) dressed past—or a more ebullient and latorial future, whether on Earth or gallooned amongst the stars. via JF Ptak Science Books/Public Domain Review Related Content: Kandinsky, Klee & Other Bauhaus Artists Designed Ingenious Costumes Like You’ve Never Seen Before Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Author Imagines in 1893 the Fashions That Would Appear Over the Next 100 Years is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 12:00p | Meditation for Artists: Learn Moebius’ Meditative Technique Called “Automatic Drawing” Meditation and art have an ancient, intertwined history in China, where the beginnings of Chan Buddhism are inseparable from landscape painting. In Japan, Zen art has constituted “a practice in appreciating simplicity,” of disappearing into the creative act, cultivating degrees of egolessness that allow an artist’s movements to become spontaneous and unhampered by second guesses. The “first Japanese artists to work in [ink],” notes the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “were Zen monks who painted in a quick and evocative manner.” They passed their techniques, and their wisdom, on to their students. Perhaps the closest analogue to this tradition in the west is comic art. Artist Ted Gula has worked with comics legends Frank Frazetta and Moebius and drawn for Disney, Marvel, and DC. As a child, he watched Jack Kirby work. “He wouldn’t speak,” says Gula. “He’d be in a trance…. The pencil would hit the paper and it wouldn’t stop until the page was complete, like it poured out.” How is that possible? Gula asked himself, astonished. Kirby had disappeared into the work. There were no preliminary sketches or rough indicators. He would draw an entire book like that, Gula says in the video above from Proko. Say what you will about the content of Kirby’s work—superhero comics aren’t to everyone’s liking. But no distaste for the nature of his storytelling diminishes Kirby’s attainment of a purely extemporaneous method he seems never to have explained to Gula in words. Later, however, while working with Moebius, Gula says, he learned the technique of “automatic drawing.” Demonstrating it for us above, Gula describes a way of drawing that shares much in common with other meditative visual art traditions. “It’s all doing very organic shapes,” he says, showing us how to “draw your mind’s eye. This takes your mind, and your mind’s eye, to a place that normally is unexplored, and it can’t help but enhance your whole view of your ability.” The ego must step aside, executive functioning isn’t needed here. “I have no idea,” Gula says, “it’s all just happening on its own.” Moebius explained it as “just letting my mind relax” and Gula has observed similar practices among all the artists he’s worked with. Gula describes automatic drawing as a natural process for the artist’s mind and hands. The interviewer, artist and teacher Sam Prokopenko, also mentions Korean artist Kim Jung Gi in their interview, who does “amazingly accurate drawings from his memory without any construction lines,” as Prokopenko says above, in a video from his “12 Days of Proko” series, which interviews well-known artists about their techniques. What’s Kim Jung Gi’s secret? Is he possessed of a superhuman, photographic memory? No, he tells Prokopenko. The secret to becoming fully immersed in the work—one that surely goes for so many pursuits, both creative and athletic—is just to do it: over and over and over and over and over again. (To many people’s disappointment, this also seems to be the secret of meditation.) In Kim Jung Gi’s case, “of course, some part of it is a talent he was born with, but we can’t overlook how much that talent was developed.” Yet we need no expert talent, either innate or developed, to get started. Automatic drawing seems to require a beginner’s mind. Related Content: Moebius Gives 18 Wisdom-Filled Tips to Aspiring Artists Watch Moebius and Miyazaki, Two of the Most Imaginative Artists, in Conversation (2004) Moebius’ Storyboards & Concept Art for Jodorowsky’s Dune Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Meditation for Artists: Learn Moebius’ Meditative Technique Called “Automatic Drawing” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | David Lynch Turns Twin Peaks into a Virtual Reality Game: Watch the Official Trailer When David Lynch and Mark Frost's Twin Peaks premiered on ABC in 1990, viewers across America were treated to a televisual experience like none they'd ever had before. Four years earlier, something similar had happened to the unsuspecting moviegoers who went to see Lynch's breakout feature Blue Velvet, an experience described as eye-opening by even David Foster Wallace. A dedicated meditator with an interest in plunging into unexplored realms of consciousness, Lynch tends to bring his audience right along with him in his work, whether that work be cinema, television, visual art, music, or comic strips. Only natural, then, that Lynch would take an interest in the artistic and experiential possibilities of virtual reality. Last year we featured the first glimpse of a Twin Peaks virtual reality experience in development, revealed at Lynch's Festival of Disruption in Los Angeles. "The best news is that the company developing the game, Collider Games, is giving creative control to Lynch," wrote Ted Mills, and now, with the release of Twin Peaks VR's official trailer, we can get a clearer idea of what Lynch has planned for players. As Laura Snoad writes at It's Nice That, Lynch has used the opportunity to revisit "well-known environments featured in the series, such as the iconic Red Room (the stripy-floored, velvet curtain-clad parallel universe where Agent Cooper meets murdered teen Laura Palmer), the Twin Peaks’ Sheriff’s Department and the pine-filled forest around the fictional Washington town." This will come as good news indeed to those of us Twin Peaks enthusiasts who've made the pilgrimage to Snoqualmie, North Bend, and Fall City, the real-life Washington towns where Lynch and his collaborators shot the series. But Twin Peak VR will offer a greater variety of challenges than snapping photos of the series' locations and chatting with bemused locals: Snoad writes that each environment is constructed like an escape room. "Solving puzzles to help Agent Cooper and Gordon Cole (the FBI agent played by Lynch himself), players will also meet some of the show’s weird and terrifying characters, from the backwards-speaking inhabitants of the Black Lodge to the terrifying Bob himself." Available via Steam on Oculus Rift, Vive, and Valve Index this month, with Oculus Quest and PlayStation VR versions scheduled, Twin Peaks VR should give a fair few virtual-reality holdouts a compelling reason to put on the goggles — much as Twin Peaks the show caused the cinéastes of the 1990s to break down and watch evening TV. Enjoying Lynch's work, whatever its medium, has always felt like plunging into a dream: not like watching his dream, but experiencing a dream he's made for us. If virtual-reality technology has finally come anywhere close to the vividness of Lynch's imagination, Twin Peaks VR will mark the next step in his artistic evolution. But for now, to paraphrase no less a Lynch fan than Wallace, the one thing we can say with total confidence is that it will be... Lynchian. via It's Nice That Related Content: Watch an Epic, 4-Hour Video Essay on the Making & Mythology of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks Twin Peaks Actually Explained: A Four-Hour Video Essay Demystifies It All David Lynch Is Creating a Virtual Reality Experience for Twin Peaks Twin Peaks Tarot Cards Now Available as 78-Card Deck David Lynch Directs a Mini-Season of Twin Peaks in the Form of Japanese Coffee Commercials Play the Twin Peaks Video Game: Retro Fun for David Lynch Fans Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. David Lynch Turns Twin Peaks into a Virtual Reality Game: Watch the Official Trailer is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/12/11 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |