[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, December 18th, 2019

- Artists who hate their hit song: People, BBC, CheetSheet.com.

- Articles about trends in music sales, such as "Will the Single Kill the Album" by Steven Guttenberg, CNet News

- Various articles who call musicians "genius," like this one about Britney Spears from The Guardian.

- Also, Ric Ocasek (from The Cars) R.I.P.

- Quincy Jones complaining about Taylor Swift

| Time | Event |

| 8:01a | The Singer or the Song? Ken Stringfellow (Posies, R.E.M., Big Star) and Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #23 Discuss

What's your relationship to music? Do you just embrace the pure sound, or do you care about who made that sound? One way of seeing where you fall on this issue is whether you care more for singles or to whole albums or careers by artists. Ken Stringfellow, who co-fronts The Posies and was a member of R.E.M. and Big Star, joins Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt to talk about what actually grabs us about music, whether being a musician yourself is a key factor in whether you pay attention to the context of a song, how music gets to your ears, singers vs. songwriters, what we think about the notion of "genius," and how this artist vs. song conflict relates to how we take in other media (e.g. favorite film directors). The ideas for this discussion mostly came from reflecting on our own experiences and habits, but we did some warm-up research into: Listen to Mark interview Ken on Nakedly Examined Music, presenting specifically some of his solo, Posies, and Big Star songs. After that was recording, Ken sang some harmonies on a tune on Mark's last album, Mark Lint's Dry Folk. Other references: "Midnight Confessions" by The Grass Roots, Lil Peep, Tom Waits's most popular album, Lou Reed is not a one-hit wonder, the scene in Slacker with a fan getting Madonna's pubic hair, Damien Rice is still working, the band Live reunited, REM on Sesame Street (no, Ken is not on camera), Ken being "world music" by playing solo in foreign countries. This episode includes bonus discussion that you can only hear by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts or start with the first episode. The Singer or the Song? Ken Stringfellow (Posies, R.E.M., Big Star) and Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #23 Discuss is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 9:00a | How Yoga Changes the Brain and May Guard Against Alzheimer’s and Dementia

Photo by Abhisek Sarda, via Wikimedia Commons I tend to be somewhat skeptical of scientific research that focuses solely on what practices like meditation do to the greyish-pinkish-white stuff inside our skulls. Humans are too complex to be treated like brains in vats. Holistic disciplines like meditation and yoga emphasize the union of mind and body, and neuroscientists have shown how mental and emotional health is as tied to the functioning of our circulatory systems and microbiomes as it is to proper brain function. On the other hand, there’s no denying the importance of brain health, given that it’s the one organ we may never be able to replace. While we may have grown accustomed to, and maybe even weary of, seeing mindfulness under the scanner, the neuroscience of yoga hasn’t received nearly as much press. This is changing for several reasons. Most prominently, “yoga has particularly gained traction as a research area of interest in its promising potential of therapy to combat the alarming increase in age-related neurogenerative diseases.” So notes a systemic review of the current literature on yoga and brain health published in the journal Brain Plasticity this past November. The authors surveyed 11 different studies, all of which preserved the typical Hatha yoga mix of postures, meditation, and breathing exercises in their methodology. Each study also “used brain-imaging techniques such as MRI, functional MRI or single-photon emission computerized tomography” to assess physical brain changes, reports Science Daily. The survey authors define yoga as “the most popular form of complementary therapy practiced by more than 13 million adults,” as well as an ancient practice that “dates back over 2000 years to ancient India.” Whether one does yoga in more spiritual or more secular contexts, its “acute and intervention effects on cognition are evident” across the entire range of studies. The research confirms much of what we might expect—yoga has a positive effect on mood, demonstrating “the potential to improve anxiety, depression, stress and overall mental health.” The survey also showed consistent findings we might not have expected. Despite the typically slow pace of a Hatha yoga routine, all the studies found evidence that “yoga enhances many of the same brain structures and functions that benefit from aerobic exercise,” as Science Daily points out. “From these 11 studies, we identified some brain regions that consistently come up, and they are surprisingly not very different from what we see with exercise research,” says lead author Neha Gotha, kinesiology and community health professor at the University of Illinois. Gotha identifies one of those benefits as an increase in the size of the hippocampus, the region of the brain that tends to shrink with age and “the structure that is first affected in dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.” Other regions affected include the amygdala, which contributes to emotional regulation, and the prefrontal cortex, which is “essential to planning, decision-making, multitasking, thinking about your options and picking the right option,” says study co-author Jessica Damoiseaux, psychology professor at Wayne State University. “Yoga is not aerobic in nature," says Gotha, "so there must be other mechanisms leading to these brain changes. So far we don’t have the evidence to identify what those mechanisms are.” The effects, however, aren’t only similar to those of more vigorous exercise; in some cases, yoga seemed even more effective. Nicole McDermott at Greatist explains that in one study Gotha conducted with 30 female colleagues, “reaction times were shorter and accuracy was greater after the yoga session compared to 20 minutes of a treadmill.” Even more surprisingly, “jogging resulted in nearly the same cognitive performance as the baseline testing when the women didn’t exercise at all.” These results should be seen as provisional and preliminary. “We need more rigorous and well-controlled intervention studies to confirm these initial findings,” Damoiseaux cautions. But they may contribute to growing evidence of the “mind-body connection” yoga helps foster. Better mood and lowered stress tend to improve brain health overall. Other studies support these conclusions, such as research showing how yoga practice over time enlarges the somatosensory cortex, which contains a “mental map” of the body and promotes greater self-awareness. No doubt we’ll see many more studies on yoga and brain function in the coming years. For the time being, the science strongly suggests that when we hit the yoga mat to limber up and de-stress, we’re also helping to proof our brains against debilitating effects of aging like memory loss and cognitive decline. Read Gotha and Damoiseaux's full survey of the neuroscience of yoga here. via Science Daily Related Content: How to Get Started with Yoga: Free Yoga Lessons on YouTube Sonny Rollins Describes How 50 Years of Practicing Yoga Made Him a Better Musician Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How Yoga Changes the Brain and May Guard Against Alzheimer’s and Dementia is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

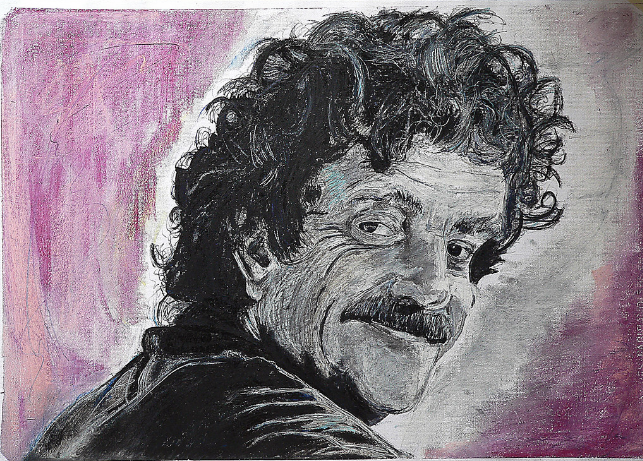

| 12:00p | Why the University of Chicago Rejected Kurt Vonnegut’s Master’s Thesis (and How a Novel Got Him His Degree 27 Years Later)

Image by Daniele Prati, via Flickr Commons Kurt Vonnegut has been gone a dozen years now, but in that time his stock in the world of American literature has only risen. Just a few months ago we featured the newly opened Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library here on Open Culture, and we've also posted about everything from his writing tips to his letters to his drawings. And we've featured his conception of "the shape of all stories" as originally laid out in his master's thesis at the University of Chicago, where between 1945 and 1947 he performed anthropological research into the Native American-inspired Ghost Dance religious movement of the late 19th century. "The fundamental idea," wrote Vonnegut, "is that stories have shapes which can be drawn on graph paper, and that the shape of a given society’s stories is at least as interesting as the shape of its pots or spearheads." None of this flew with the anthropology department. In an essay in his book Palm Sunday Vonnegut explains the unanimous rejection of his thesis, "The Fluctuations Between Good and Evil in Simple Tasks," due to the fact that "it was so simple and looked like too much fun. One must not be too playful." Opting not to have a second go before the committee, the still-young Vonnegut — with his harrowing experience in the Second World War only a couple of years behind him — decided to take a job as a publicist at General Electric instead. In 1950, while still employed at GE, he would first publish a piece of fiction: "Report on the Barnhouse Effect" in Collier's magazine. "Years later," says the University of Chicago Chronicle's obituary for Vonnegut, "the university accepted Cat’s Cradle as Vonnegut’s thesis, awarding him an A.M. in 1971." "This was not an honorary degree but an earned one," said Vonnegut in a 1973 interview, "given on the basis of what the faculty committee called the anthropological value of my novels. I snapped it up most cheerfully and I continue to have nothing but friendly feelings for the University." Indeed, Vonnegut called his time as a Phoenix "the most stimulating years of my life." Generations of readers have found in Vonnegut's work — not just Cat’s Cradle, the one that finally got him his academic credentials, but other novels like Mother Night, Breakfast of Champions, and of course Slaughterhouse-Five as well — some of the most stimulating writing to come out of postwar America. And yet Vonnegut, as he writes in Palm Sunday, continued to regard his first master's thesis as "my prettiest contribution to my culture." The more successful the creator, it can often seem, the more dear he holds his failures. Related Content: Kurt Vonnegut Diagrams the Shape of All Stories in a Master’s Thesis Rejected by U. Chicago Kurt Vonnegut: Where Do I Get My Ideas From? My Disgust with Civilization Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Why the University of Chicago Rejected Kurt Vonnegut’s Master’s Thesis (and How a Novel Got Him His Degree 27 Years Later) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | An Introduction to Surrealism: The Big Aesthetic Ideas Presented in Three Videos Before surrealism became Merriam Webster's word of the year in 2016 for its useful description of reality, it applied to art that incorporates the bizarre juxtapositions of dream logic. We know it from the films of David Lynch and paintings of Salvador Dalí. We may not, however, know it from the poetry of Andre Breton, “but the movement actually began in literature,” points out the Scottish National Gallery introductory video above. Breton, influenced by Freud and Rimbaud, railed against mediocrity, positivism, the ‘realistic attitude,” and the “reign of logic” in his 1924 “Manifesto of Surrealism.” If this sounds somewhat familiar, it’s because Surrealism was “built on the ashes of Dada." The first group of artists who worked under the term Surrealism included Tristan Tzara, who had penned the “Dada Manifesto” only six years earlier. Where Tzara had claimed that “Dada means nothing,” Breton declared Surrealism in favor of dream states, symbolism, and “the marvelous.” He also defined the term—a word he took from the Symbolist poet Guillaume Apollinaire—“once and for all."

The artists and writers who coalesced around Breton represented a hodgepodge of styles, from the pure abstraction of Joan Miro to the hyperrealist fantasies of Dali and playful symbolist conundrums of Magritte and art pranks of Marcel Duchamp. As artists, theirs was foremost an aesthetic radicalism invested in Freudian examinations of the psyche through the imagery of the unconscious. “But when [the movement] emerged in Europe,” notes the PBS Art Assignment video above, “during the tenuous, turbulent years following World War I and leading up to World War II, Surrealism positioned itself not as an escape from life, but as a revolutionary force within it.” Breton joined the French Communist Party in 1927, was tossed out in 1933, and in 1934 delivered a speech, which became a pamphlet entitled “What is Surrealism?” Here Breton redefined Surrealism as an anti-fascist position, “a living movement, that is to say a movement undergoing a constant process of becoming…. surrealism has brought together and is still bringing together diverse temperaments individually obeying or resisting a variety of bents.” Here he alludes to previous political turmoil in the Surrealist ranks: “The fact that certain of the first participants in surrealist activity have thrown in the sponge and have been discarded has brought about the retiring from circulation of some ways of thinking.” The reference is partly to Dali, whom Breton expelled from the Surrealist group that same year for “the glorification of Hitlerian fascism.” As World War II began, many Surrealists fled Europe for the United States. Breton traveled the Caribbean, settled in New York, and developed a friendship with Martinican poet, writer, and statesman Aime Cesaire. He met Trotsky, Frida Kahlo, and Diego Rivera in Mexico, and participated in the burgeoning Surrealist movement in the U.S. and Latin America. The influence of Breton and his Surrealist literary peers on mid-century fiction and poetry in the decolonizing global south was significant. Breton “insisted art be created for revolution not profit”—points out the video above, “Surrealism: The Big Ideas." Dali, on the other hand,“wasn’t really into all that.” The painter retreated to the U.S. in 1940 with his wife Gala, spending his time on both coasts and becoming a popular sensation. America “offered Dali endless opportunities for his talents.” Dali “introduced Surrealism to the general public, and made it fun!... America loved it, and him. They made Dali a celebrity," and he helped popularize a Surrealist aesthetic in Hollywood film and Madison Avenue advertising. But to really understand the movement, we must not look only to its visual vocabulary and its influence on pop culture, but also to the poetry, philosophy, and politics of its founder. Related Content: When The Surrealists Expelled Salvador Dalí for “the Glorification of Hitlerian Fascism” (1934) A Brief, Visual Introduction to Surrealism: A Primer by Doctor Who Star Peter Capaldi When The Surrealists Expelled Salvador Dalí for “the Glorification of Hitlerian Fascism” (1934) Salvador Dalí Goes to Hollywood & Creates Wild Dream Sequences for Hitchcock & Vincente Minnelli Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness An Introduction to Surrealism: The Big Aesthetic Ideas Presented in Three Videos is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2019/12/18 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |