[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, January 4th, 2021

| Time | Event |

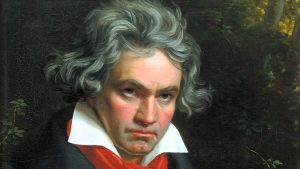

| 9:00a | Did Beethoven Use a Broken Metronome When Composing His String Quartets? Scientists & Musicians Try to Solve the Centuries-Old Mystery   When it comes to classical composers, Beethoven was pretty metal. But was he writing some kind of classical thrash? Hardcore orchestrations too fast for the average musician to play? 66 out of 135 of Beethoven’s tempo markings made with his new metronome in the early 1800s seem “absurdly fast and thus possibly wrong,” researchers write in a recent American Mathematical Society article titled “Was Something Wrong with Beethoven’s Metronome?” Indeed, the authors go on, “many if not most of Beethoven’s markings have been ignored by latter day conductors and recording artists” because of their incredible speed. Since the late 19th century and into the age of recorded music, conductors have slowed Beethoven’s quartets down, so that we have all internalized them at a slower pace than he presumably meant them to be played. “These pieces have throughout the years entered the subconscious of professional musicians, amateurs and audiences, and the tradition,” writes the Beethoven Project, “handed down by the great quartets of yesteryear.” Slower tempos have “become a norm against which all subsequent performances are judged.” Eybler Quartet violist Patrick Jordan found out just how deeply musicians and audiences have internalized slower tempi when he became interested in playing and recording at Beethoven’s indicated speeds in the mid-80s. “Finding a group of people who were prepared to actually take [Beethoven’s metronome marks] seriously—that was a 30-year wait,” he tells CBC. “A huge amount of our labour required that we un-learn those things; that we get notions of what we’ve heard recorded and played in concerts many times out of our heads and try to put in what Beethoven, at least at some point in his life, believed and thought highly enough to make a note of and publish.” But did he? The subject of Beethoven’s metronome has been a source of controversy for some time. A few historians have theorized that the inventor of the metronome, Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, “something of a mechanical wizard,” Smithsonian writes, and also something of a disreputable character, sabotaged the device he presented to the composer in 1815 as a peace offering after he sued Beethoven for the rights to a composition. (Mälzel actually stole the metronome’s design from a Dutch mechanic named Dietrich Winkel.) But most musicologists and historians have dismissed the theory of deliberate trickery. Still, the problem of too-fast tempi persists. “The literature on the subject is enormous,” admit the authors of the American Mathematical Society study. Their research suggests that Beethoven’s metronome was simply broken and he didn’t notice. Likewise data scientists at the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid have theorized that the composer, one of the very first to use the device, misread the machine, a case of musical misprision in his reaction against what he called in 1817 “these nonsensical terms allegro, andante, adagio, presto….” Theorists may find the tempi hard to believe, but the Toronto-based Eybler Quartet was undeterred by their skepticism. “I don’t think there’s any evidence to suggest that the mechanism itself was [faulty],” says Jordan, “and we know from [Beethoven’s] correspondence and contemporaneous accounts that he was very concerned that his metronome stay in good working order and he had it recalibrated frequently so it was accurate.” Jordan instead credits the punishing speeds to Romanticism’s passionate individualism, and to the fact that “Beethoven was not always so very nice.” Maybe, instead of soothing his audiences, he wanted to shock them and set their hearts racing. Who are we to believe? Questions of tempo can be fraught in classical circles (witness the reactions to Glenn Gould’s absurdly slow versions of Bach.) The metronome was supposed to solve problems of rhythmic imprecision. Instead, at least in Beethoven’s case, it reinscribed them in compositions that boldly challenge ideas of what a classical quartet is supposed to sound like, which makes me think he knew exactly what he was doing. Related Content: How Did Beethoven Compose His 9th Symphony After He Went Completely Deaf? Stream the Complete Works of Bach & Beethoven: 250 Free Hours of Music Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Did Beethoven Use a Broken Metronome When Composing His String Quartets? Scientists & Musicians Try to Solve the Centuries-Old Mystery is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 12:00p | Dial-a-Poem: The Groundbreaking Phone Service That Let People Hear Poems Read by Patti Smith, William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg & More (1968)

Dialing a poem today, I’m connected to Joe Brainard, who died of AIDS-related pneumonia in 1994, reading an excerpt of “I Remember.” He stumbles over some words. It’s exciting. There’s a feeling of immediacy. When the reading ends in an old-fashioned dial tone, I immediately think of a half-dozen friends I’d like to call (assuming they respond to something that’s not a tag or text). “Take down this number,” I’d say. “641-793-8122. Don’t ask questions. Just call it. You’ll love it.” And they probably would, though they wouldn’t hear the same recording I did. As Dial-A-Poem‘s founder, the late John Giorno, remarked in a 2012 interview:

Giorno established Dial-A-Poem in 1968, placing ten landlines connected to reel-to-reel answering machines in a room in New York City’s Architectural League:

In its first four-and-a-half months of operation, Dial-A-Poem logged 1,112,237 incoming calls, including some from listeners overseas. (The original phone number was 212-628-0400.) The hours of heaviest traffic suggested that a lot of bored office workers were sneaking a little poetry into their 9-to-5 day. Dial-A-Poem reconceived of the telephone as a new media device:

Featured poets included such heavy hitters as William S. Burroughs, Patti Smith, Allen Ginsberg, Ted Berrigan, Robert Creeley, Sylvia Plath, Charles Bukowski, and Frank O’Hara (who “only liked you if you wrote like him”). The content was risqué, political, a direct response to the Vietnam War, the political climate, and social conservatism. No one bothered with rhymes, and inspiration was not necessarily the goal. Unlike Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and other career-minded artists who he hung out with (and bedded), Giorno never made a secret of his homosexuality. Sexually explicit and queer content had a home at Dial-a-Poem. Meanwhile, Dial-a-Poem was featured in Junior Scholastic Magazine, and dialing in became a homework assignment for many New York City Public School students. Two twelve-year-old boys nearly scuppered the project when one of their mothers caught them giggling over the Jim Carroll poem, above, and raised a ruckus with the Board of Ed, who in turn put pressure on the telephone company to discontinue service. The New York State Council on the Arts’ lawyers intervened, a win for horny middle schoolers… and poetry!

For anyone interested, an album called You’re A Hook: The 15 Year Anniversary Of Dial-A-Poem (1968-1983) was released in 1983. Vinyl copies are still floating around. If you dial 641.793.8122, you can still access recordings from an archive of poetry, notes SFMoMA. via Messy Nessy Related Content: Stream Classic Poetry Readings from Harvard’s Rich Audio Archive: From W.H. Auden to Dylan Thomas Cartoonist Lynda Barry Reveals the Best Way to Memorize Poetry Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She most recently appeared as a French Canadian bear who travels to New York City in search of food and meaning in Greg Kotis’ short film, L’Ourse. Follow her @AyunHalliday Dial-a-Poem: The Groundbreaking Phone Service That Let People Hear Poems Read by Patti Smith, William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg & More (1968) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | Discover Tokyo’s Museum Dedicated to Parasites: A Unique and Disturbing Institution

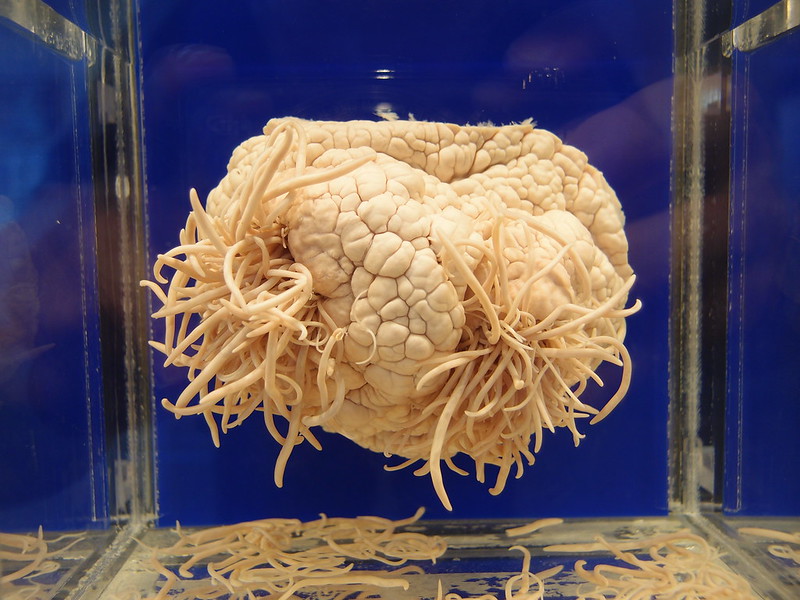

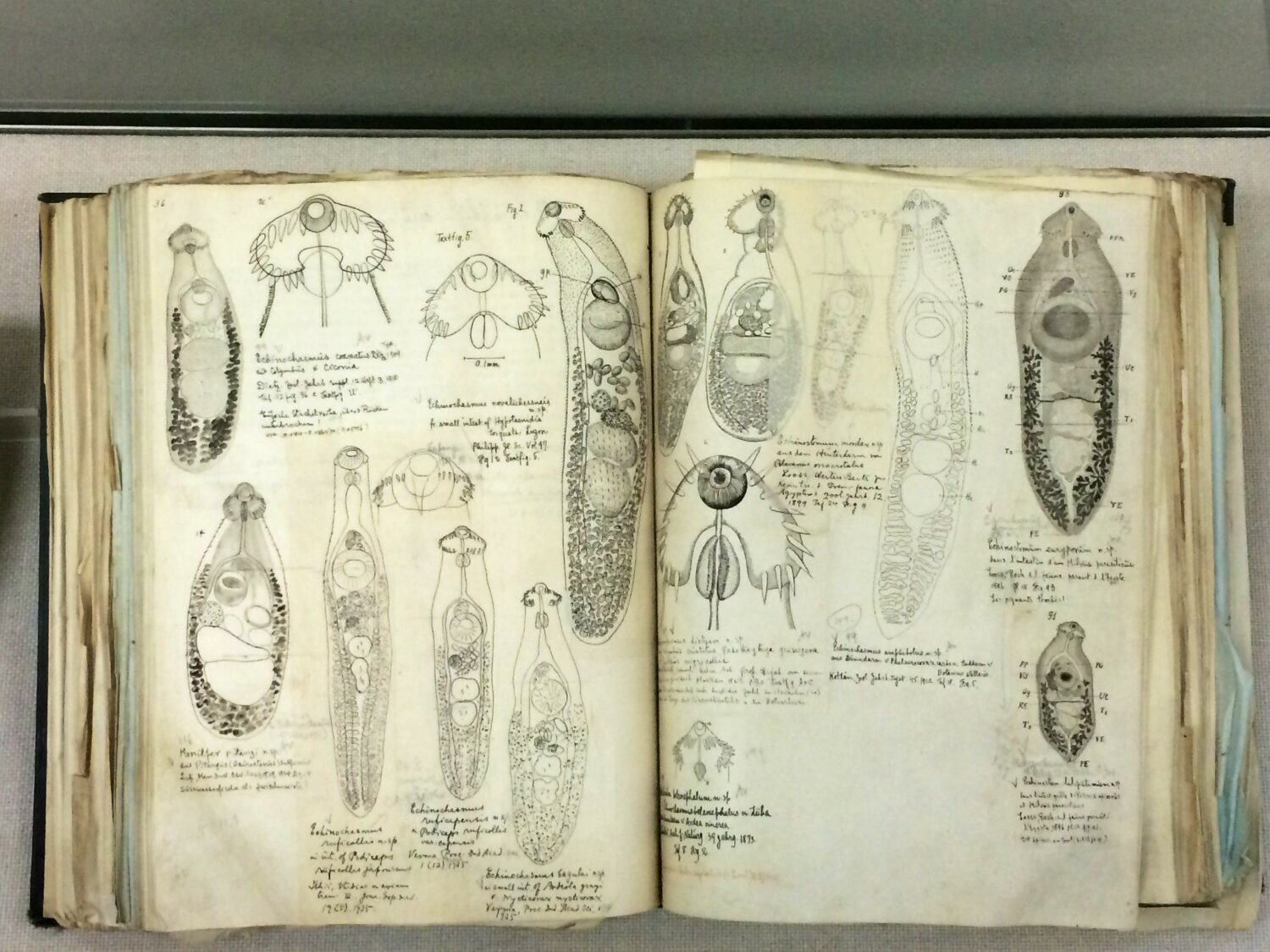

Photo by Guilhem Vellut Weary as we are of hearing about not just the coronavirus but viruses in general, shall we we turn our attention to parasites instead? The Meguro Parasitological Museum has been concentrating its intellectual and educational energies in that direction since 1953. Located in the eponymous neighborhood of Tokyo, it houses more than 60,000 species of parasite, with more than 300 on display at any given time. “On the first floor we present the ‘Diversity of Parasites’ displaying various types of parasite specimens with accompanying educational movies,” write directors Midori Kamegai and Kazuo Ogawa. “The second floor exhibits are ‘Human and Zoonotic Parasites’ showing parasite life cycles and the symptoms they cause during human infection.”

Photo by Guilhem Vellut We’ve here included a few choice pictures from the museum, but as Culture Trip’s India Irving warns, “the real-life specimens are far worse than the photographs; some of the displays present preserved parasites actually popping out of their animal hosts.” She names as “the most repulsive item on view” a tapeworm “roughly the size of a London bus — it is the longest tapeworm in world and is exhibited alongside a rope of the same length so visitors can get a physical feel for just how enormous it actually was.” What other parasitological museum could hope to compete with that? Not that any have tried: the Meguro Parasitological Museum proudly describes itself as the only such institution in the world.

Photo by Guilhem Vellut “Some of the displays are merely disturbing, while others are slightly more ghastly,” writes Mental Floss’ Jake Rossen. “If you’ve ever wanted to see a photo of a tropical bug prompting a human testicle to swell to the size of a gym bag, this is the place for you.” Like many other museums, it did shut down for a time earlier in the pandemic, but has been open again since June. (If you happen not to be a Japanese speaker, guides in English and other languages are available in both text and app form.) If current conditions have nevertheless kept Japan itself out of your reach, you can have a look at the Meguro Parasitological Museum’s unique offerings through this Flickr gallery — which gets many of us as close to these organisms as we care to be.

via Mental Floss Related Content: Discover the Japanese Museum Dedicated to Collecting Rocks That Look Like Human Faces The First Museum Dedicated to Japanese Folklore Monsters Is Now Open Take a Virtual Tour of the Mütter Museum and Its Many Anatomically Peculiar Exhibits Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. Discover Tokyo’s Museum Dedicated to Parasites: A Unique and Disturbing Institution is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/01/04 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |