[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, January 7th, 2021

- “The Surprising Origin Story of Wonder Woman” by Jill Lepore

- “Does Wonder Woman 1984 Have a Steve Trevor Problem?” by Sarah El-Mahmoud

- “The Warped Morality of ‘Wonder Woman 1984’” by Dani Di Placido

- “How Wonder Woman 1984 Reboots the DC Hero’s Forgotten Superpower” by Eric Francisco

- “How ‘Wonder Woman 1984’ Villain Maxwell Lord Stays True to the Comics” by Graeme McMillan

- And from our former guest, Noah Berlatsky: “HBO Max’s ‘Wonder Woman 1984’ Stars a Trump-y Villain, Gal Gadot’s Charm and a Garbled Message“

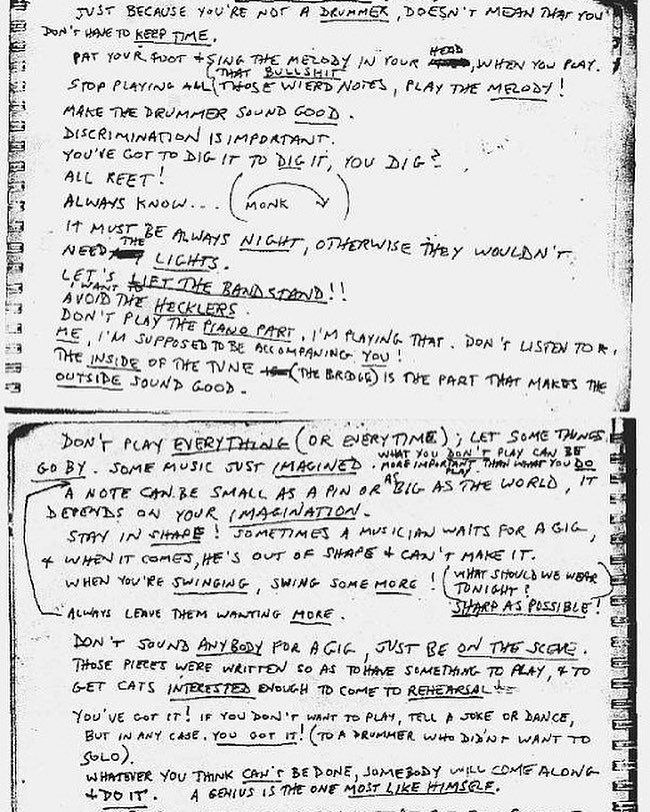

- Just because you’re not a drummer, doesn’t mean you don’t have to keep time.

- Pat your foot & sing the melody in your head, when you play.

- Stop playing all that bullshit, those weird notes, play the melody!

- Make the drummer sound good.

- Discrimination is important.

- You’ve got to dig it to dig it, you dig?

- All reet!

- Always know… (monk )

- It must be always night, otherwise they wouldn’t need the lights.

- Let’s lift the band stand!!

- I want to avoid the hecklers.

- Don’t play the piano part, I’m playing that.

- Don’t listen to me. I’m supposed to be accompanying you!

- The inside of the tune (the bridge) is the part that makes the outside sound good.

- Don’t play everything (or every time); let some things go by. Some music just imagined. What you don’t play can be more important than what you do.

- Always leave them wanting more.

- A note can be small as a pin or as big as the world, it depends on your imagination.

- Stay in shape! Sometimes a musician waits for a gig, & when it comes, he’s out of shape & can’t make it.

- When you’re swinging, swing some more!

- (What should we wear tonight?) Sharp as possible!

- Don’t sound anybody for a gig, just be on the scene.

- These pieces were written so as to have something to play, & to get cats interested enough to come to rehearsal.

- You’ve got it! If you don’t want to play, tell a joke or dance, but in any case, you got it! (to a drummer who didn’t want to solo).

- Whatever you think can’t be done, somebody will come along & do it. A genius is the one most like himself.

- They tried to get me to hate white people, but someone would always come along & spoil it.

| Time | Event |

| 8:01a | Wonder Woman 1984 in Context – Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #76

The holiday film release season has now passed, having issued only one real blockbuster, which is the return of Wonder Woman. This week’s Pretty Much Pop likewise offers a returning hero: Our college-going guest from ep. 33 on heroine journeys has now grown into a grad student in comics history, and she brings her deep WW knowledge to consider with your hosts Erica Spyres, Mark Linsenmayer, and Brian Hirt. Part of the relevant context is the 2017 biopic Professor Marston and the Wonder Women, which revealed the unorthodox views of WW’s creator, and so of course this shows up in how WW judges us: She’s not just a Captain America-style patriot, but a foreigner who in the new film compassionately condemns our 80s greed and dishonesty. But do the themes actually make sense? And what’s with having her love interest return from the dead, hijacking another man’s body with no acknowledgment that that’s very skeevy? Also, how does the depiction of WW’s homeland compare to other feminist utopias like Herland and “Sultana’s Dream”? Does it matter that WW was created by and initially aimed primarily at males? We learn a little about the post-Marston WW (who couldn’t join the Justice League, which was for boys only!) and talk about the ’70s TV show, the outfits, the villains, and WW in love. Here are a few supplementary articles: Hear more of this podcast at prettymuchpop.com. This episode includes bonus discussion you can access by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts.

Wonder Woman 1984 in Context – Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #76 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

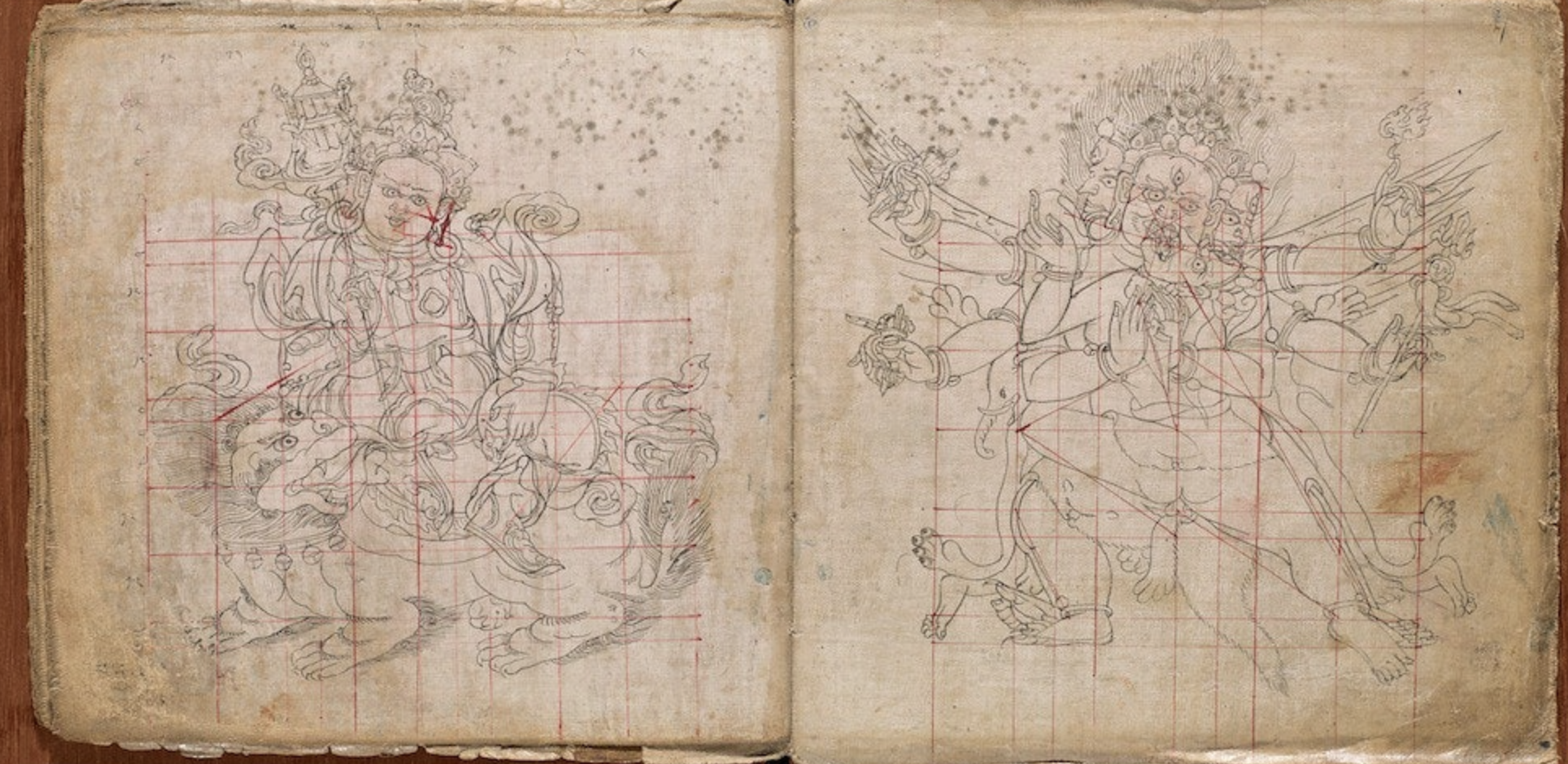

| 9:00a | How to Draw the Buddha: Explore an Elegant Tibetan Manual from the 18th-Century

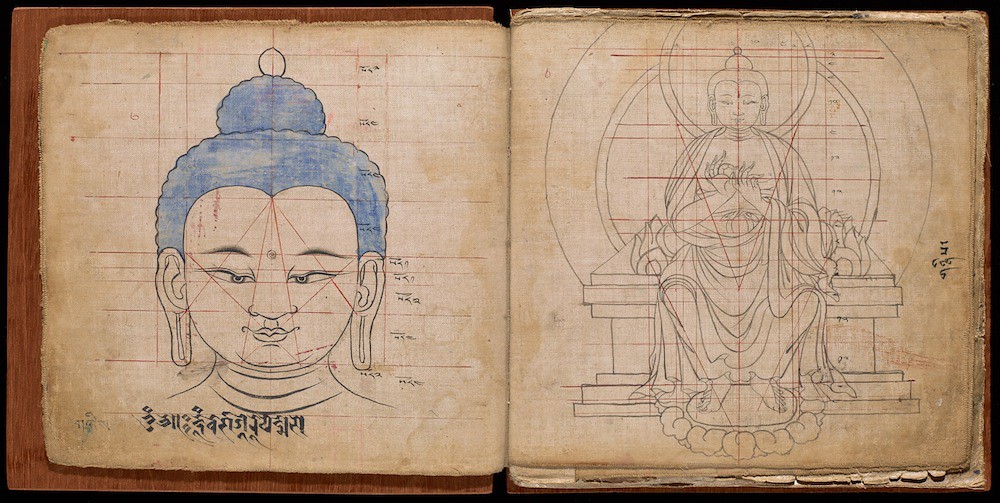

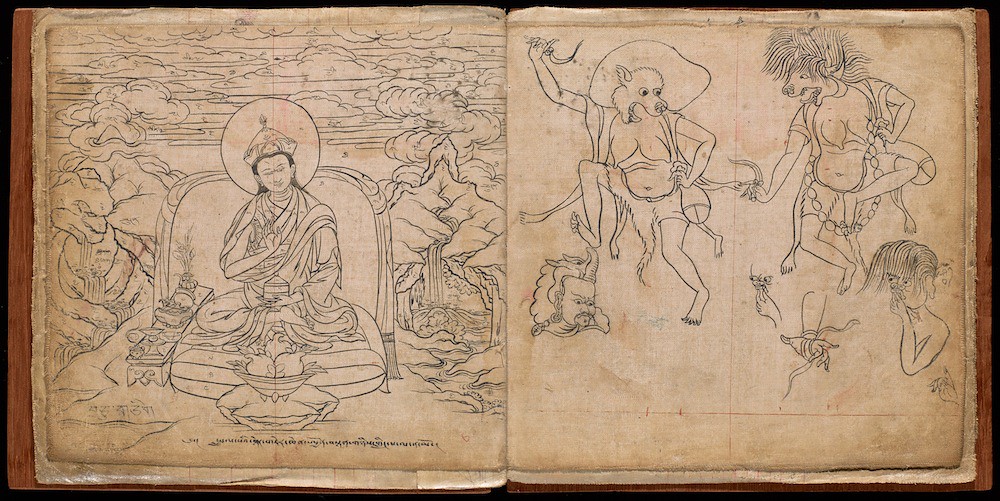

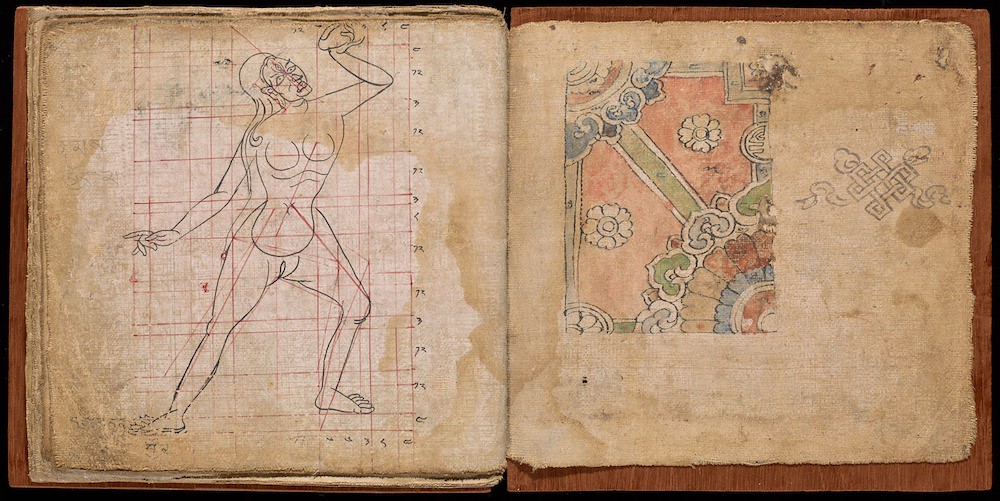

Some religions prohibit the depiction of their sacred personages. Tibetan Buddhism isn’t quite so strict, but it does ask that, if you’re going to depict the Buddha, you do it right. Hence aids like the Tibetan Book of Proportions, which provides “36 ink drawings showing precise iconometric guidelines for depicting the Buddha and Bodhisattva figures.” That description comes from the Public Domain Review, where you can behold many of those pages. Printed in the 18th century, “the book is likely to have been produced in Nepal for use in Tibet.” Now you’ll find it at the Getty Center in Los Angeles, which had made the book free to read at its digital collections.

To read it properly, of course, you’ll have to know your Newari script and Tibetan numerals. But even without them, anyone can appreciate the elegance of not just the book’s recommended proportions — all presented on a standardized and notated grid — but of the book itself as well. By the time this volume appeared, the printing used for texts related to Tibetan Buddhism had long since shown itself to be a cut above: take the 15th-century collection of recitation texts, previously featured here on Open Culture, printed forty years before the Gutenberg Bible. Only a printing culture that had mastered this level of detail could produce a book like the Tibetan Book of Proportions, visual exactitude being its entire raison d’être.

“The concept of the ‘ideal image’ of the Buddha emerged during the Golden Age of Gupta rule, from the 4th to 6th century,” says the Public Domain Review. During that Indian empire’s dominance, the importance of such depictions extended even beyond proportions to details like “number of teeth, color of eyes, direction of hairs.” Surely when it comes to showing one who has attained nirvana — or a bodhisattva, the designation for those on their way to nirvana — one can’t be too careful. Nevertheless, artworks in the form of the Buddha (of which the Victoria and Albert Museum offer a small sampling on their web site) have taken different shapes in different times and places. No matter how well-defined the ideal, the earthly realm always finds a way to introduce some variety.

Related Content: Breathtakingly Detailed Tibetan Book Printed 40 Years Before the Gutenberg Bible The World’s Largest Collection of Tibetan Buddhist Literature Now Online Leonard Cohen Narrates Film on The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Featuring the Dalai Lama (1994) Tibetan Musical Notation Is Beautiful Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. How to Draw the Buddha: Explore an Elegant Tibetan Manual from the 18th-Century is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 12:00p | An Animated Introduction to Baruch Spinoza: The “Philosopher’s Philosopher” The so-called Enlightenment period encompasses a surprisingly diverse collection of thinkers, if not always in ethnic or national origin, at least in intellectual disposition, including perhaps the age’s most influential philosopher, the “philosopher’s philosopher,” writes Assad Meymandi. Baruch Spinoza did not fit the image of the bewigged philosopher-gentleman of means we tend to popularly associate with Enlightenment thought. He was born to a family of Sephardic Portuguese Marranos, Jews who were forced to convert to Catholicism but who reclaimed their Judaism when they relocated to Calvinist Amsterdam. Spinoza himself was “excommunicated by Amsterdam Jewry in 1656,” writes Harold Bloom in a review of Rebecca Goldstein’s Betraying Spinoza: “The not deeply chagrined 23-year-old Spinoza did not become a Calvinist, and instead consorted with more liberal Christians, particularly Mennonites.” Spinoza read “Hebrew, paleo-Hebrew, Aaramaic, Greek, Latin, and to some degree Arabic,” writes Meymandi. “He was not a Muslim, but behaved like a Sufi in that he gave away all his possessions to his step sister. He was heavily influenced by Al Ghazali, Baba Taher Oryan, and Al Farabi.” He is also “usually counted, along with Descartes and Leibniz, as one of the three major Rationalists,” Loyola professor Blake D. Dutton notes at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, a thinker who “made significant contributions in virtually every area of philosophy.” One might say without exaggeration that it is impossible to understand Enlightenment thinking without reading this most heterodox of thinkers, and in particular reading his Ethics, which is itself no easy task. In this work, as Alain de Botton puts it in his School of Life introduction to Spinoza above, the philosopher tried “to reinvent religion, moving it away from something based on superstition and direct divine intervention to something that is far more impersonal, quasi-scientific, and yet also, at times, serenely consoling.” One might draw several lines from Spinoza to Sagan and also to Wittgenstein and other modern skeptics. His critiques of such cherished concepts as prayer and a personal relationship with a deity did not qualify him as a religious thinker in any orthodox sense, and he was derided as an “atheist Jew” in his time. But he took religion, and religious awe, very seriously, even if Spinoza’s God is indistinguishable from nature. To imagine that this great, mysterious entity should bend the rules to suit our individual needs and desires constitutes a “deeply distorted, infantile narcissism” in Spinoza’s estimation, says de Botton. For Spinoza, a mature ethics instead consists in finding out how the universe works and accepting it, rather in the way of the Stoics or Nietzsche’s use of the Stoic idea of amor fati. It is within such acceptance, what Bloom calls Spinoza’s “icy sublimity,” that true enlightenment is found, according to Spinoza. Or as the de Botton video succinctly puts it: “The free person is the one who is conscious of the necessities that compel us all,” and who—instead of railing against them—finds creative ways to live within their limitations peacefully. Related Content: An Animated Introduction to Voltaire: Enlightenment Philosopher of Pluralism & Tolerance Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness An Animated Introduction to Baruch Spinoza: The “Philosopher’s Philosopher” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:25p | Thelonious Monk’s List of 25 Tips for Musicians

At some point, Monk took Lacy aside and gave his some advice which Lacy wrote down, 25 pieces of advice to be exact. In the video below, from Neely’s always interesting channel (we’ve previously written about him here), he and Krock go through the 25 points and comment on each one. For those who love to hear musicians (or any artist) talk shop, this is wonderful stuff. Some of the advice is such as befits a live musician—“Pat your foot & sing the melody in your head, when you play”, “Don’t play the piano part, I’m playing that”, “When you’re swinging, swing some more!,” and “A note can be small as a pin or as big as the world, it depends on your imagination.” Others are more crucial to the business, especially “Don’t sound anybody for a gig, just be on the scene.” That is: if you around the scene enough, and show your worth, you will get asked to play. But just cold asking won’t get you anywhere. Also, when asked what to wear to a gig, Monk advises: “Sharp as possible!” which you could indeed say of Monk. Other advice is more mystical: “You’ve got to dig it to dig it, you dig?” “What you don’t play can be more important than what you do.” And the one that gets quoted the most, “A genius is the one most like himself.” That’s true when it comes to Monk or any of the giants of jazz. To hear Monk, or Coltrane, or Miles Davis play is to hear the artist, the genius, and the person, not just the melody or the instrument. It reminds me of the great Harry Partch quote: “The creative person shows himself naked. And the more vigorous his creative act, the more naked he appears – sometimes totally vulnerable, yet always invulnerable in the sense of his own integrity.” And maybe that’s why we keep coming back to them, long after their physical bodies have left this plane of existence. The full list is as follows: Related Content: Thelonious Monk Bombs in Paris in 1954, Then Makes a Triumphant Return in 1969 Andy Warhol Creates Album Covers for Jazz Legends Thelonious Monk, Count Basie & Kenny Burrell A Child’s Introduction to Jazz by Cannonball Adderley (with Louis Armstrong & Thelonious Monk) Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here. Thelonious Monk’s List of 25 Tips for Musicians is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/01/07 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |