[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, January 12th, 2021

| Time | Event |

| 9:02a | Discover the First Illustrated Book Printed in English, William Caxton’s Mirror of the World (1481)

The printing history of early English books may not seem like the most fascinating subject in the world, but if you mention the name William Caxton to a book historian, you may get a fascinating lecture nonetheless. Caxton, the merchant and diplomat who introduced the printing press to England in 1476, was an unusually enterprising figure. He first learned the trade in Cologne and was pressured to begin printing in English after the success of his translation of the Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, a series of stories based on Homer’s Iliad. His first known printed book was Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, and he went on to print translations of classical and medieval texts from the French. Caxton’s (often inaccurate) translations became so popular that, like Chaucer, he introduced new standards into the language as a whole with his use of court Chancery English. The books printed at the time also give us a fascinating look at how the printed book evolved slowly as a new source of scientific information and a means of literary innovation. The so-called Gutenberg Revolution did not usher in a radical break with the late medieval past so much as a gradual evolution away from its adherence to classical and church authorities and chivalric romance stories. It would take early modern writers like Shakespeare, Cervantes, and Francis Bacon to truly revolutionize the possibilities of print.

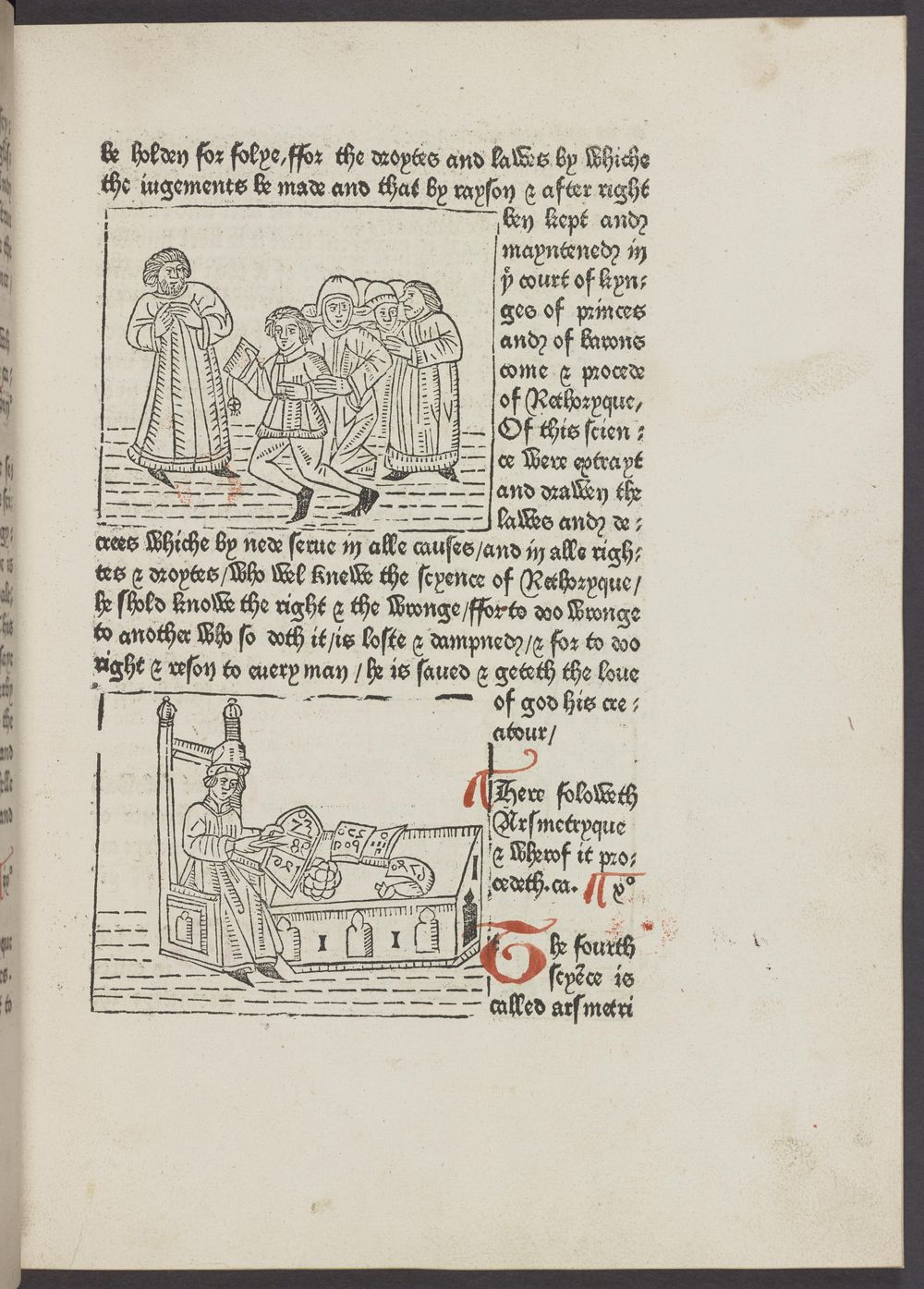

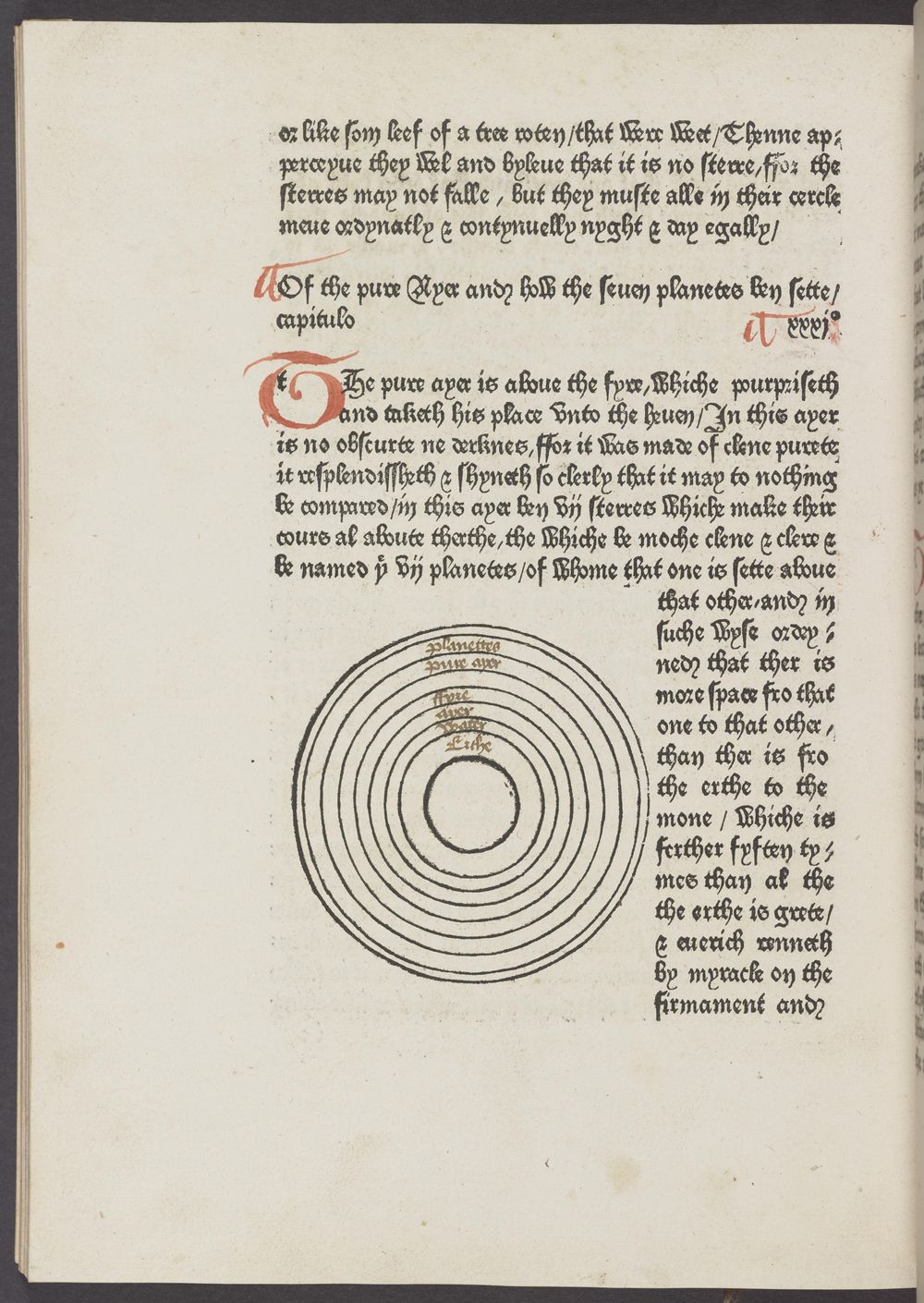

The first illustrated book Caxton printed in English offers an excellent example of early printing history’s reliance on reproducing extant medieval ideas rather than disseminating new ones. The Mirror of the World, first written in French as L’image du monde, was an encyclopedia based on a 12th century text by Honorius Augustodunensis called Imago mundi. “Encyclopedic texts were popular throughout the Middle Ages,” Glasgow University Library notes. “During this period it was commonly believed that it was possible to create one volume digests of all knowledge,” drawing solely on classical and Biblical authorities. In the introduction to Caxton’s text, we are told that the book “treateth of the world & of the wonderful dyuision [division] thereof.” We are quite a long way yet from the Royal Society’s motto Nullius in verba, or “take no one’s word for it.” But Caxton’s press made several medieval manuscript prose works available for the first time to a new readership. “Evidence of early ownership of copies of his editions,” writes the British Library, “suggests the social breadth of that audience, including royalty, nobility, gentry, the mercantile classes and religious houses.” Caxton was “not content to simply draw on pre-existing markets for manuscripts.” And he would eventually use print “to create new markets for novel and different kinds of writing,” such as the 1485 publication of Thomas Malory’s contemporary Arthurian romance, Le Morte D’arthur.

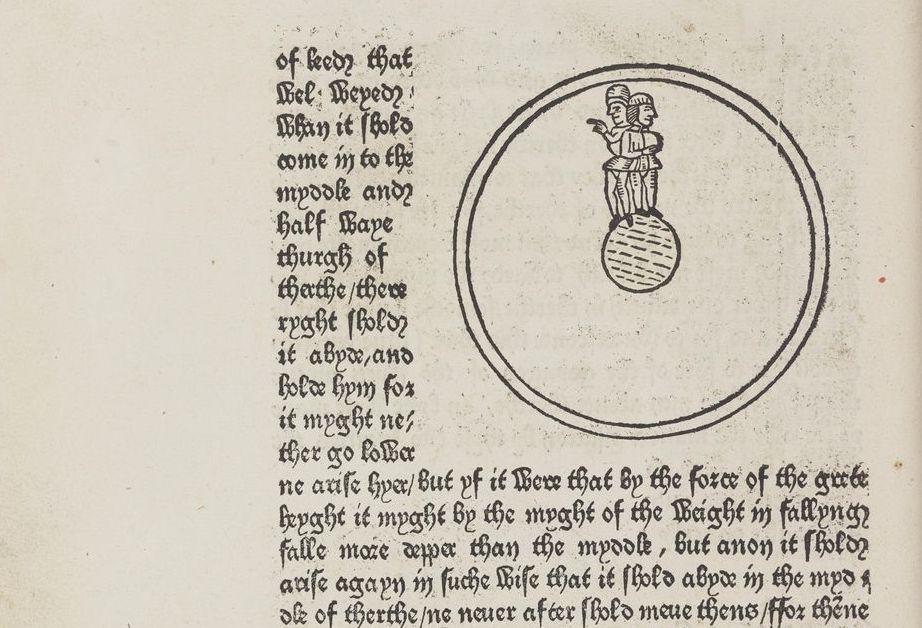

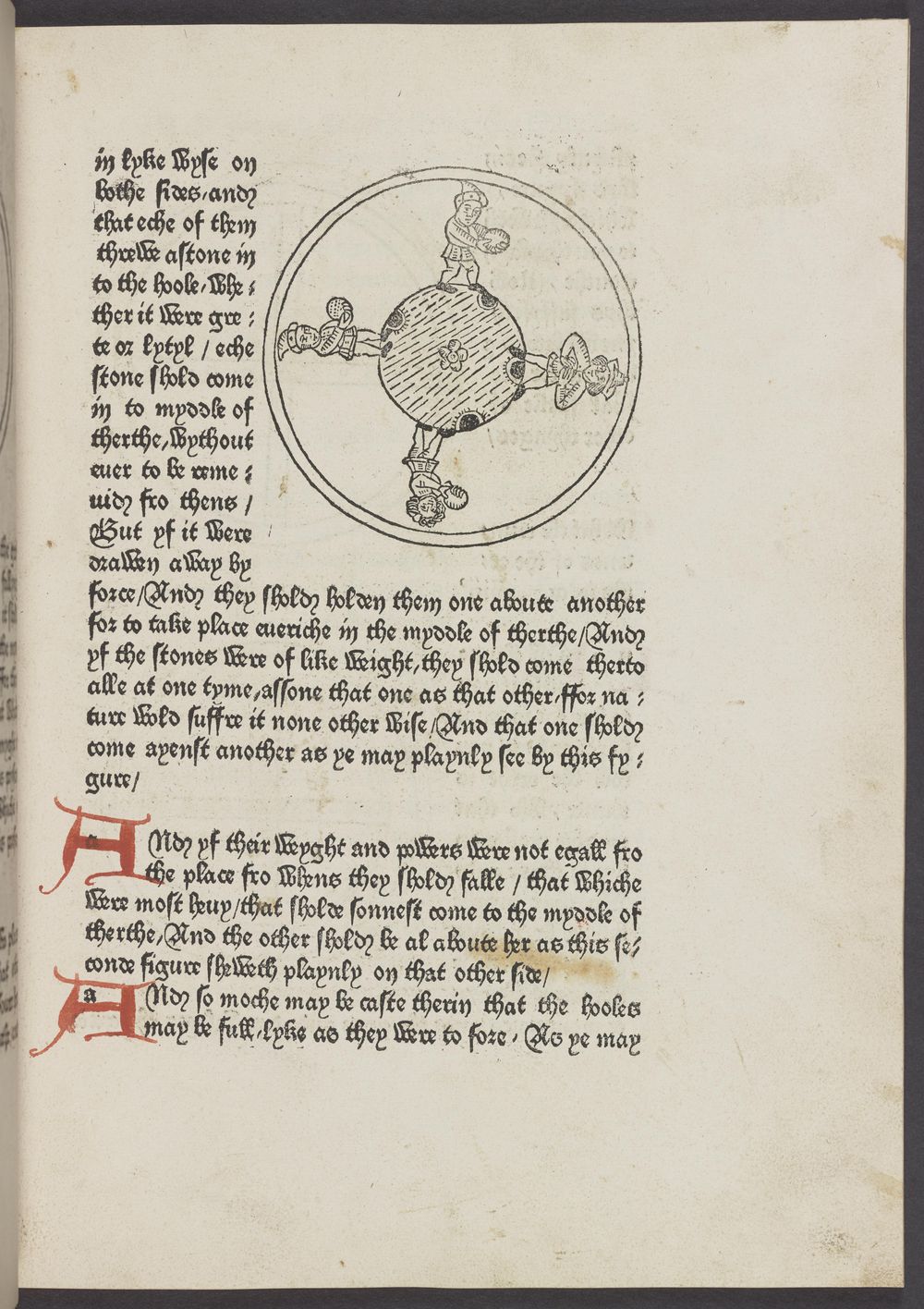

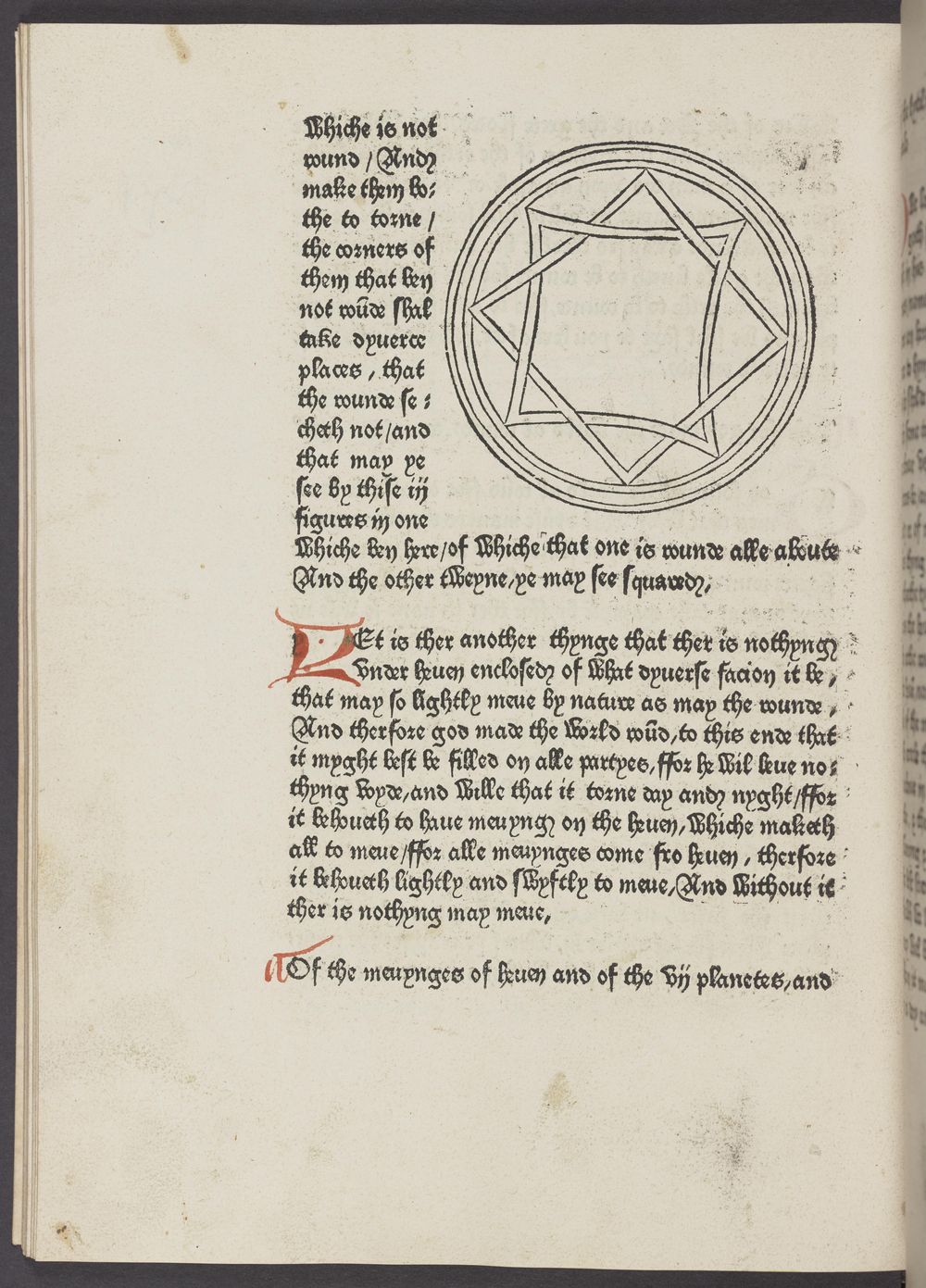

Representing the confident but cramped worldview of the medieval sciences, the Mirror of the World is “ambitious,” Allison Meier writes at Hyperallergic, dispelling any notion of a flat Earth, with descriptions of “large ideas like the roundness of the Earth and why we experience day and night… Along with some historical information, there are descriptions of the Earth, the solar system, and eclipses. The round shape of the Earth is illustrated by two men who stand back-to-back, walking away from each other and meeting again in a circle. Another describes the same idea with a rock tossed through a hole sliced in the world, with it tumbling out the other side.”

Mike Millward of the Blackburn Museum describes the images further:

These illustrations, notes John T. McQuillan, assistant curator of printed books at the Pierpont Morgan library, were remarkably preserved from the original French text of two centuries earlier. “Print only carried on existing manuscript and textual traditions,” he notes, “and did not radically alter them, at first. Anyone who wanted to buy this text would have expected it to have these specific illustrations, and Caxton provided that to them.” Pierpont Morgan himself, who owned several of Caxton’s early printed books, “valued Caxton even over Gutenberg,” Meier writes, and “had the printer painted on the ceiling of his library’s East Room.” Another rare books library, Princeton’s Scheide, which holds perhaps the finest collection of early European and American printing in the world, features a scanned full-text edition of Mirror of the World, the first illustrated book printed in England and a work that sits squarely on the threshold between the medieval and the modern, and that challenges our ideas about both designations.

Related Content: One of World’s Oldest Books Printed in Multi-Color Now Opened & Digitized for the First Time See the Oldest Printed Advertisement in English: An Ad for a Book from 1476 Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Discover the First Illustrated Book Printed in English, William Caxton’s Mirror of the World (1481) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 12:00p | How Lava Lamps Help Secure the Internet Try not to think too hard about the concept of randomness — and especially about the question of how, exactly, one generates a random number. Most of us, of course, simply ask a computer to do it. But how can a computer, which by its very nature follows unambiguous directions in a predictable manner, come up with a truly random number, in the literal sense of the word? As far as the everyday purposes for which we might need “random” numbers — setting the combination on a lock, for instance — merely unpredictable numbers suffice. But where, exactly, can we draw the line between unpredictability and randomness? Albert Einstein famously pronounced that “God does not play dice with the universe,” drawing on a metaphor still central to humanity’s conception of randomness. Dice provide “random” numbers in that, when thrown, they’re subject to too many physical factors — an area of some interest for Einstein — for us to reliably guess which way they’ll land. And so we find ourselves again delivered back from randomness into unpredictability. But achieving ever-greater unpredictability, which has proven invaluable to fields like cryptography, has necessitated combining computers with analog physical phenomena essentially similar to the rolling of dice. Using a somewhat less ancient technology, internet security provider Cloudflare has taken a step closer to genuine randomness. “Every time you log in to any website, you’re assigned a unique identification number,” explains Wired‘s Ellen Airhart. “It should be random, because if hackers can predict the number, they’ll impersonate you.” But who could predict “the goopy mesmeric swirlings of oil, water, and wax” within a lava lamp, let alone an entire wall covered with them? “Cloudflare films the lamps 24/7 and uses the ever-changing arrangement of pixels to help create a superpowered cryptographic key.” Theoretically, Airhart acknowledges, “bad guys could sneak their own camera into Cloudflare’s lobby to capture the same scene,” but the company also “films the movements of a pendulum in its London office and records the measurements of a Geiger counter in Singapore to add more chaos to the equation. Crack that, Russians.” Constant vigilance against a threat from Russia aided by psychedelic bedroom light fixtures? You’d be forgiven for feeling unstuck in time, partially transported to the reality of half a century ago. But then, Cloudflare is headquartered in San Francisco — a city where the groundbreaking and the groovy haven’t parted ways just yet. Related Content: Stephen Fry Explains Cloud Computing in a Short Animated Video “The Bay Lights,” The World’s Largest LED Light Sculpture, Debuts in San Francisco How Art Nouveau Inspired the Psychedelic Designs of the 1960s Visualizing WiFi Signals with Light Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. How Lava Lamps Help Secure the Internet is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | A Look Inside William S. Burroughs’ Bunker

From 1974 to 1982, writer William S. Burroughs lived in a former locker room of a 19th-century former-YMCA on New York City’s Lower East Side. When he moved on, his stuff, including his worn out shoes, his gun mags, the typewriter on which he wrote Cities of the Red Night, and half of The Place of Dead Roads, a well-worn copy of The Medical Implications of Karate Blows, and a lamp made from a working Civil war-era rifle, remained. His friend, neighbor, tourmate, and occasional lover, poet John Giorno preserved “The Bunker” largely as Burroughs had left it, and seems to delight in rehashing old times during a 2017 tour for the Louisiana Channel, above. It’s hard to believe that Burroughs found Giorno to be “pathologically silent” in the early days of their acquaintance:

According to Burroughs’ companion, editor and literary executor, James Grauerholz, during this period in Burroughs’ life, “John was the person who contributed most to William’s care and upkeep and friendship and loved him.” Giorno also prepared Burroughs’ favorite dish—bacon wrapped chicken—and joined him for target practice with the blowgun and a BB gun whose projectiles were forceful enough to penetrate a phonebook. Proximity meant Giorno was well acquainted with the schedules that governed Burroughs’ life, from waking and writing, to his daily dose of methadone and first vodka-and-Coke of the day. He was present for many dinner parties with famous friends including Andy Warhol, Lou Reed, Frank Zappa, Allen Ginsberg, Debbie Harry, Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Patti Smith, who recalled visiting the Bunker in her National Book Award-winning memoir, Just Kids:

All Giorno had to do was walk upstairs to enjoy Burroughs’ company, but all other visitors were subjected to stringent security measures, as described by Victor Bockris in With William Burroughs: A Report from the Bunker:

Although Burroughs lived simply, he did make some modifications to his $250/month rental. He repainted the battleship gray floor white to counteract the lack of natural light. It’s pretty impregnable. He also installed an Orgone Accumulator, the invention of psychoanalyst William Reich, who believed that spending time in the cabinet would improve the sitter’s mental, physical, and creative wellbeing by exposing them to a mysterious universal life force he dubbed orgone energy. (“How could you get up in the morning with a hangover and go sit in one of these things?” Giorno chuckles. “The hangover is enough!”) Included in the tour are excerpts of Giorno’s 1997 poem “The Death of William Burroughs.” Take it with a bit of salt, or an openness to the idea of astral body travel. As per biographer Barry Miles, Burroughs died in the Lawrence Memorial Hospital ICU in Kansas, a day after suffering a heart attack. His only visitors were James Grauerholz, his assistant Tom Peschio, and Dean Ripa, a friend who’d been expected for dinner the night he fell ill. Poetic license aside, the poem provides extra insight into the men’s friendship, and Burroughs’ time in the Bunker:

Related Content: How William S. Burroughs Influenced Rock and Roll, from the 1960s to Today William S. Burroughs’ Class on Writing Sources (1976) Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She most recently appeared as a French Canadian bear who travels to New York City in search of food and meaning in Greg Kotis’ short film, L’Ourse. Follow her @AyunHalliday A Look Inside William S. Burroughs’ Bunker is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:19p | Peanuts Plays Yes’ “Roundabout” Digital filmmaker Garren Lazar gives us a creative parody video and a badly-needed mental health break. Enjoy. To watch previous Peanuts parodies of songs by Queen, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Journey & more, click here. Would you like to support the mission of Open Culture? Please consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. Also consider following Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and sharing intelligent media with your friends. Or sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. Related Content Umberto Eco Explains the Poetic Power of Charles Schulz’s Peanuts How Franklin Became Peanuts‘ First Black Character, Thanks to a Caring Schoolteacher (1968)

Peanuts Plays Yes’ “Roundabout” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/01/12 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |