[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, January 13th, 2021

- Always, always speak respectfully: “Without respect, compassion, and empathy, no one will open their mind or heart to you. No one will listen.”

- Go private: Using direct messages when online “prevents discussion from getting embarrassing for the poster, and it implies a genuine compassion and interest in conversation rather than a desire for public shaming.”

- Test the waters first: “You can ask what it would take to change their mind, and if they say they will never change their mind, then you should take them at their word and not bother engaging.”

- Agree: “Conspiracy theories often feature elements that everyone can agree on.”

- Try the “truth sandwich”: “Use the fact-fallacy-fact approach, a method first proposed by linguist George Lakoff.”

- Or use the Socratic method: This “challenges people to come up with sources and defend their position themselves.”

- Be very careful with loved ones: “Biting your tongue and picking your battles can help your mental health.”

- Realize that some people don’t want to change, no matter the facts.

- If it gets bad, stop: “One r/ChangeMyView moderator suggested ‘IRL calming down’: shutting off your phone or computer and going for a walk.”

- Every little bit helps. “One conversation will probably not change a person’s mind, and that’s okay.”

| Time | Event |

| 9:00a | Social Psychologist Erich Fromm Diagnoses Why People Wear a Mask of Happiness in Modern Society (1977)

There are more think pieces published every day than any one person can read about our current moment of social disintegration. But we seem to have lost touch with the insights of social psychology, a field that dominated popular intellectual discourse in the post-war 20th century, largely due to the influential work of German exiles like Erich Fromm. The humanist philosopher and psychologist’s “prescient 1941 treasure Escape from Freedom,” writes Maria Popova, serves as what he called “‘a diagnosis rather than a prognosis,’ written during humanity’s grimmest descent into madness in WWII, laying out the foundational ideas on which Fromm would later draw in considering the basis of a sane society,” the title of his 1955 study of alienation, conformity, and authoritarianism. Fromm “is an unjustly neglected figure,” Kieran Durkin argues at Jacobin, “certainly when compared with his erstwhile Frankfurt School colleagues, such as Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno.” But he has much to offer as a “grounded alternative” to their critical theory, and his work “reveals a distinctly more optimistic and hopeful engagement with the question of radical social change.” Nonetheless, Fromm well understood that social diseases must be identified before they can be treated, and he did not sugarcoat his diagnoses. Had society become more “sane” thirty-plus years after the war? Fromm didn’t think so. In the 1977 interview clip above, Fromm defends his claim that “We live in a society of notoriously unhappy people,” which the interviewer calls an “incredible statement.” Fromm replies:

Contrast this observation with Albert Camus’ 1959 statement, “Today happiness is like a crime—never admit it. Don’t say ‘I’m happy’ otherwise you will hear condemnation all around.” Were Fromm and Camus observing vastly different cultural worlds? Or is it possible that in the intervening years, forced happiness—akin to the socially coerced emotions Camus depicted in The Stranger—had become normalized, a screen of denial stretched over existential dread, economic exploitation, and social decay? Fromm’s diagnosis of forced happiness resonates strongly with The Stranger (and Billie Holiday), and with the image-obsessed society in which we live most of our lives now, presenting various curated personae on social media and videoconferencing apps. Unhappiness may be a byproduct of depression, violence, poverty, physical illness, social alienation… but its manifestations produce even more of the same: “Them that’s got shall get / Them that’s not shall lose.” If you’re unhappy, says Fromm, “you lose credit on the market, you’re no longer a normal person or a capable person. But you just have to look at people. You only have to see how behind the mask there is unrest.” Have we learned how to look at people behind the mask? Is it possible to do so when we mostly interact with them from behind a screen? These are the kinds of questions Fromm’s work can help us grapple with, if we’re willing to accept his diagnosis and truly reckon with our unhappiness. Related Content: Albert Camus Explains Why Happiness Is Like Committing a Crime—”You Should Never Admit to it” (1959) How Much Money Do You Need to Be Happy? A New Study Gives Us Some Exact Figures Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Social Psychologist Erich Fromm Diagnoses Why People Wear a Mask of Happiness in Modern Society (1977) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

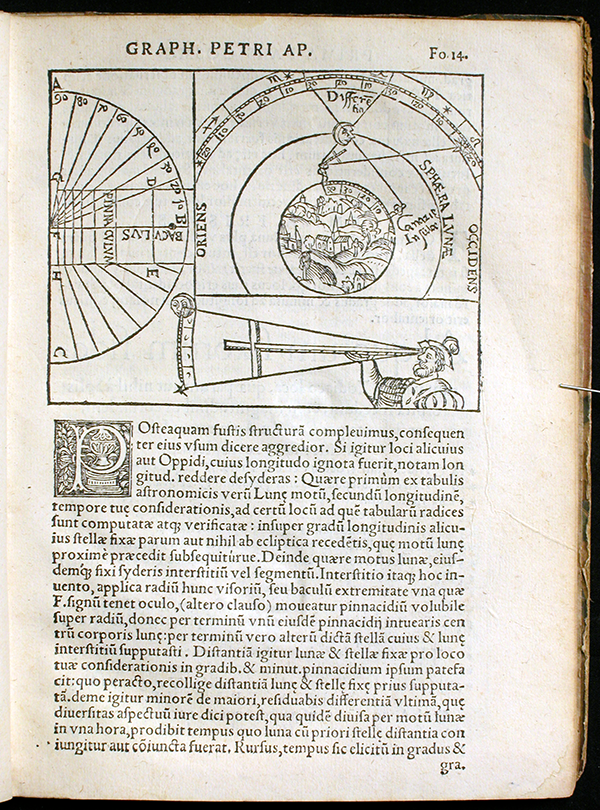

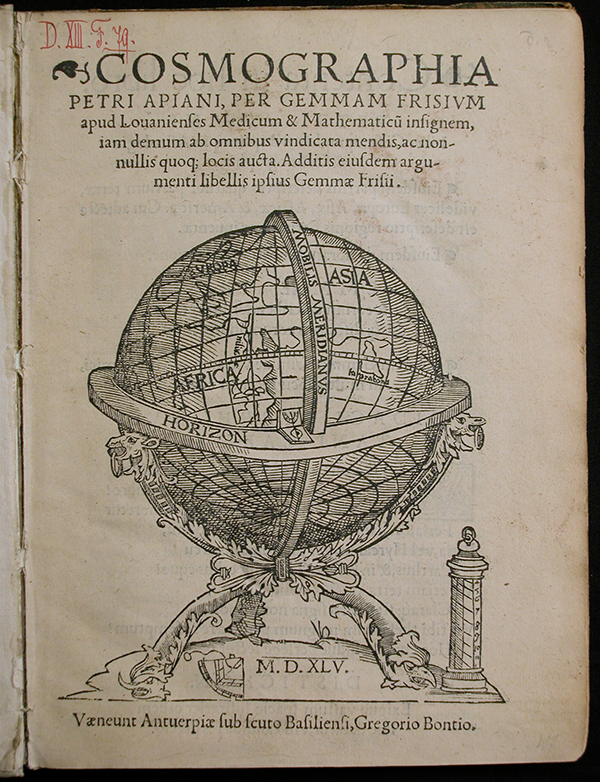

| 3:03p | A 16th-Century Astronomy Book Featured “Analog Computers” to Calculate the Shape of the Moon, the Position of the Sun, and More Pop-up book enthusiasts like Ellen Rubin will know what volvelles are; you and I may not, but if you’ve ever moved a paper wheel or slider on a page, you’ve used one. The volvelle first emerged in the medieval era, not as an amusement to liven up children’s books but as a kind of “analog computer” embedded in serious scientific works. “The volvelles make the practical nature of cosmography clear,” writes Katie Taylor at Cambridge’s Whipple Library, which holds a copy of Cosmographia. “Readers could manipulate these devices to solve problems: finding the time at different places and or one’s latitude, given the height of the Sun above the horizon.”

Apian originally included three such volvelles in Cosmographia. Later, his disciple Gemma Frisius, a Dutch physician, instrument maker and mathematician, produced expanded editions that included another. “In all its forms,” writes Swetz, “the book was extremely popular in the 16th century, going through 30 printings in 14 languages.” Despite the book’s success, it’s not so easy to come by a copy in good (indeed working) condition nearly 500 years later. If these descriptions of its pages and their volvelles have piqued your curiosity, you can see these ingenious paper devices in action in these videos tweeted out by Atlas Obscura. As with planets themselves, you can’t fully appreciate them until you see them move for yourself. Related Content: An Illustrated Map of Every Known Object in Space: Asteroids, Dwarf Planets, Black Holes & Much More When Astronomer Johannes Kepler Wrote the First Work of Science Fiction, The Dream (1609) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. A 16th-Century Astronomy Book Featured “Analog Computers” to Calculate the Shape of the Moon, the Position of the Sun, and More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00p | How to Talk with a Conspiracy Theorist: What the Experts Recommend Why do people pledge allegiance to views that seem fundamentally hostile to reality? Maybe believers in shadowy, evil forces and secret cabals fall prey to motivated reasoning. Truth for them is what they need to believe in order to get what they want. Their certainty in the justness of a cause can feel as comforting as a warm blanket on a winter’s night. But conspiracy theories go farther than private delusions of grandeur. They have spilled into the streets, into the halls of the U.S. Capitol building and various statehouses. Conspiracy theories about a “stolen” 2020 election are out for blood. As distressing as such recent public spectacles seem at present, they hardly come near the harm accomplished by propaganda like Plandemic—a short film that claims the COVID-19 crisis is a sinister plot—part of a wave of disinformation that has sent infection and death rates soaring into the hundreds of thousands. We may never know the numbers of people who have infected others by refusing to take precautions for themselves, but we do know that the number of people in the U.S. who believe conspiracy theories is alarmingly high. A Pew Research survey of adults in the U.S. “found that 36% thought that these conspiracy theories” about the election and the pandemic “were probably or definitely true,” Tanya Basu writes at the MIT Technology Review. “Perhaps some of these people are your family, your friends, your neighbors.” Maybe you are conspiracy theorist yourself. After all, “it’s very human and normal to believe in conspiracy theories…. No one is above [them]—not even you.” We all resist facts, as Cass Sunstein (author of Conspiracy Theories and Other Dangerous Ideas) says in the Vox video above, that contradict cherished beliefs and the communities of people who hold them. So how do we distinguish between reality-based views and conspiracy theories if we’re all so prone to the latter? Standards of logical reasoning and evidence still help separate truth from falsehood in laboratories. When it comes to the human mind, emotions are just as important as data. “Conspiracy theories make people feel as though they have some sort of control over the world,” says Daniel Romer, a psychologist and research director at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center. They’re airtight, as Wired shows below, and it can be useless to argue. Basu spoke with experts like Romer and the moderators of Reddit’s r/ChangeMyView community to find out how to approach others who hold beliefs that cause harm and have no basis in fact. The consensus recommends proceeding with kindness, finding some common ground, and applying a degree of restraint, which includes dropping or pausing the conversation if things get heated. We need to recognize competing motivations: “some people don’t want to change, no matter the facts.” Unregulated emotions can and do undermine our ability to reason all the time. We cannot ignore or dismiss them; they can be clear indications something has gone wrong with our thinking and perhaps with our mental and physical health. We are all subjected, though not equally, to incredible amounts of heightened stress under our current conditions, which allows bad actors like the still-current U.S. President to more easily exploit universal human vulnerabilities and “weaponize motivated reasoning,” as University of California, Irvine social psychologist Peter Ditto observes. To help counter these tendencies in some small way, we present the resources above. In Bill Nye’s Big Think answer to a video question from a viewer named Daniel, the longtime science communicator talks about the discomfort of cognitive dissonance. “The way to overcome that,” he says, is with the attitude, “we’re all in this together. Let’s learn about this together.” We can perhaps best approach those who embrace harmful conspiracy theories by not immediately telling them that we know more than they do. It’s a conversation that requires some intellectual humility and acknowledgement that change is hard and it feels really scary not to know what’s going on. Below, see an abridged version of MIT Technology Review’s ten tips for reasoning with a conspiracy theorist, and read Basu’s full article here. Related Content: Constantly Wrong: Filmmaker Kirby Ferguson Makes the Case Against Conspiracy Theories Neil Armstrong Sets Straight an Internet Truther Who Accused Him of Faking the Moon Landing (2000) Michio Kaku & Noam Chomsky School Moon Landing and 9/11 Conspiracy Theorists Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How to Talk with a Conspiracy Theorist: What the Experts Recommend is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/01/13 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |