[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, January 19th, 2021

| Time | Event |

| 9:00a | Wilhelm Reich’s Orgone Energy Accumulator Was Beloved by William S. Burroughs and Banned by the FDA: Find Plans to Build the Controversial Device Online

Was Austrian Marxist psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich a trenchant socio-political thinker or a total crank? A fraud or a prophet? Maybe a little from each column, at different times during the course of his bizarre career. An enthusiastic student of Sigmund Freud, Reich applied his teacher’s theories of repressed libido to the frightening political theater of the 1930s, writing against the spread of Nazism in his prescient 1933 book The Mass Psychology of Fascism. Here, Reich brought Marx and Freud together to argue that sexual inhibition and fear led to arrested development and submission to authoritarianism. Reich was “a sexual evangelist,” Christoper Turner writes at The Guardian, “who held that satisfactory orgasm made the difference between sickness and health.” His work was banned and burned by the Nazis, and he fled to a succession of Scandinavian countries, then to the U.S. in 1939, “by which time his former psychoanalytic colleagues were questioning his sanity.” The primary reason for their suspicion: Reich’s devotion to what he called “orgone,” an all-pervasive sexual energy that permeates the universe… according to Reich. Orgone and related concepts appear in his early work, but by the end of the 1930s, they came to entirely dominate his thinking. “In the strange and colorful history of pseudoscience, Wilhelm Reich’s ‘discovery’ of orgone—a substance that’s not only a life force, but indeed makes up the very fabric of space—must surely be a watershed,” writes Matt Simon at Wired. Reich intensified his belief in the glowing blue energy of orgone with the invention of the Orgone Energy Accumulator, an isolation box that supposedly charged those who sat inside it with the power of orgone. The device went through a few iterations (see the use of the “orgone blanket, above), until its final form of a metal-lined box roughly the size of a wardrobe or telephone booth. Reich’s influence on 20th century culture goes far beyond the creation of this weird device. He might be said to have predicted and precipitated what he himself called the “sexual revolution.” (“No power on earth will stop it,” Reich wrote in the 30s.) Critics dismissed his belief in the liberating potential of free love as a “genitial utopia.” Their scorn mattered little to the countercultural figures who picked up and disseminated his work. “Almost a century” after Reich’s invention of orgone, writes Simon, “his bonkers ideas live on,” including the notion that nearly every health condition can be traced to an imbalance of orgone energy. The Orgone Accumulator was popularized by William S. Burroughs, a true believer—as he was in many things, from Scientology to Shamanism—and an enthusiastic promoter of “life in orgone boxes.” (Jack Kerouac called Burroughs’ accumulator a “mystical outhouse” in On the Road.) Burroughs swore by the accumulator and wrote a 1977 article for Oui magazine in which he defended Reich’s claims that time spent in the sealed box might cure cancer—a claim that prompted the FDA to file an injunction against Reich in 1954 to stop use of the device and literature pertaining to it. “Reich continued profiting from the accumulators,” writes Simon, “and the court found him in contempt of the injunction. He was sentenced to federal prison, where he died in 1957.” Devotees of his work have defended him ever since. (“Who is the FDA,” wrote Burroughs indignantly, “to deprive cancer patients of any treatment that could be efficacious?”). James DeMeo, Ph.D., director of the Orgone Biophysical Research Laboratory in Ashland Oregon, has recently released the 3rd, revised and expanded, edition of his Orgone Accumulator Handbook, a thorough reference guide, “with construction plans.” Should you have the desire to build your own “mystical outhouse,” DeMeo’s text would seem to be a definitive reference. Proceed at your own risk. Wilhelm Reich’s orgone therapy remains squarely on a list of treatments unapproved by the FDA. The FBI, on the other hand, who “have a whole section on their website dedicated to Wilhelm Reich,” notes Mary Bellis, found no cause to prosecute the Austrian psychologist. “In 1947,” they note, “a security investigation concluded that neither the Orgone Project nor any of its staff were engaged in subversive activities.” But what could have been more subversive to the post-war U.S. establishment than maintaining the world’s ills could be cured by really good sex? Download a free copy of DeMeo’s book here. Related Content: A Look Inside William S. Burroughs’ Bunker The Famous Break Up of Sigmund Freud & Carl Jung Explained in a New Animated Video Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Wilhelm Reich’s Orgone Energy Accumulator Was Beloved by William S. Burroughs and Banned by the FDA: Find Plans to Build the Controversial Device Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 12:00p | The Deadliest Garden in the World: Visit Alnwick’s Poison Garden in Northumberland, England The mind reels to think of all the early humans who sacrificed themselves, unwittingly, in the prehistoric quest to learn which plants were safe to eat, which were suitable for healing, and which would maim or kill whoever who touched them. Even now, of course, the great majority of us rely on experts to make these distinctions for us. Unless we’re steeped in field training and/or folk knowledge, it’s safe to say most of us wouldn’t have a clue how to avoid poisoning ourselves in the wild. This need not overly concern us on a visit to The Poison Garden, however. Nestled in manicured lanes at Alnwick Garden, “one of north England’s most beautiful attractions,” Natasha Geiling writes at Smithsonian, the Poison Garden includes such infamous killers as hemlock, Atropa belladonna (a.k.a. Deadly Nightshade), and Strychnos nux-vomica, the source of strychnine, in its collections. Just don’t touch the plants and you should be fine. Oh, and also, guides tell visitors, “don’t even smell them.” It should go without saying that tasting is out. The Poison Garden is hardly the main attraction at Alnwick, in Northumberland. The castle itself was used as the setting for Hogwarts in the first two Harry Potter films. The 14 acres of controversial modern landscape gardens–designed by the flamboyant Jane Percy, Duchess of Northumberland–have become famous in their own right, in part for violating “England’s architectural patrimony,” a scandal you can read about here. (One garden designer and critic called it a “popular entertainment, the dream of a girl who looks like Posh and lives at Hogwarts.”) The duchess responds to criticism of her extravagant designs with a shrug. “A lot of my ideas come from Las Vegas and Euro Disney,” she admits. The Poison Garden has a much more venerable source, the Orto Botanico in Padua, the oldest extant academic botanical garden, founded in 1545, with its own poison garden that dates to the time of the Medicis. After a visit, Percy “became enthralled with the idea of creating a garden of plants that could kill instead of heal,” writes Geiling. She thought of it, specifically, as “a way to interest children.” As the duchess says:

What child doesn’t wonder about such things? And if we teach kids how to avoid poisonous plants, they can keep the rest of us alive should we have to retreat into the woods and become foragers again. The Poison Garden also grows plants from which common recreational drugs derive, like cannabis and cocaine, “as a jumping-off point for drug education,” Geiling points out. Provided visitors follow the rules, the garden is safe, “although some people still occasionally faint from inhaling toxic fumes,” Alnwick Garden’s website warns. And while it’s designed to attract and educate kids, there’s a little something for everyone. Percy’s favorite poisonous plant, for example, Brugmansia, or angel’s trumpet, acts as a powerful aphrodisiac before it kills. She explains with glee that “Victorian ladies would often keep a flower from the plant on their card tables and add small amounts of its pollen to their tea to incite an LSD-like trip.” You can learn many other fascinating facts about plants that kill, and do other things, at Alnwick’s Poison Garden when the world opens up again. Related Content: Oliver Sacks Promotes the Healing Power of Gardens: They’re “More Powerful Than Any Medication” What Voltaire Meant When He Said That “We Must Cultivate Our Garden”: An Animated Introduction Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Deadliest Garden in the World: Visit Alnwick’s Poison Garden in Northumberland, England is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | How Levi’s 501 Jeans Became Iconic: A Short Documentary Featuring John Baldessari, Henry Rollins, Lee Ranaldo & More In his memoir Living Carelessly in Tokyo and Elsewhere, the American Japanologist John Nathan remembers evenings in the 1960s spent with Yukio Mishima, whose work he translated into English. “I listened raptly as he recited passages from The Tale of the Heike that revealed the fierceness and delicacy of Japan’s warrior-poets, or showed me the fine calibration of the Chinese spectrum,” Nathan writes. “One night he stood up abruptly from behind his desk, asked me to wait a minute, and left the room. When he came back he had changed into a pair of blue jeans and a thick black leather belt. He explained that he had been sandpapering the jeans to make them identical to the pair Marlon Brando had worn in The Wild One.” Even a figure like Mishima, who within a few years would die in an ultranationalistic ritual suicide after a hopeless attempted coup, felt the allure of American blue jeans. Though Nathan doesn’t note whether Mishima’s pair were genuine Levi’s 501s, the exacting standards to which Mishima held himself in all respects would seem to demand that measure of authenticity. “Authenticity,” of course, is a quality from which Levi Strauss & Co. have drawn a great deal of value for their brand, their signature riveted denim product going back as it does nearly a century and a half, to a time when rugged pants were in great demand from the miners of California’s gold rush. But it was in the economically flush and newly media-saturated decades after the Second World War that jeans took their hold on the American imagination, and soon on the world’s. The pants, the myth, and the legend star in The 501 Jean: Stories of an Original, a three–part series of short documentaries produced by Levi’s themselves and narrated by American folk singer Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. Its gallery of 501-wearers includes such job titles as Musician, Photographer, Garmentologist, Biker, Creative Director, Music/Style Consultant, and Urban Cowboy. Conceptual artist John Baldessari discusses the childhood love of cowboy shows that lodged jeans permanently into his worldview. Album designer Gary Burden brings out his own work, a copy of Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush, to demonstrate the impact of jeans on popular music. That both Burden and Baldessari have passed away since these videos’ production underscores the current fast departure of the generations who took jeans from the realm of the utilitarian into that of the iconic — some of whose members have doubtless chosen to be buried in their 501s. Related Content: Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletterBooks on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram. How Levi’s 501 Jeans Became Iconic: A Short Documentary Featuring John Baldessari, Henry Rollins, Lee Ranaldo & More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

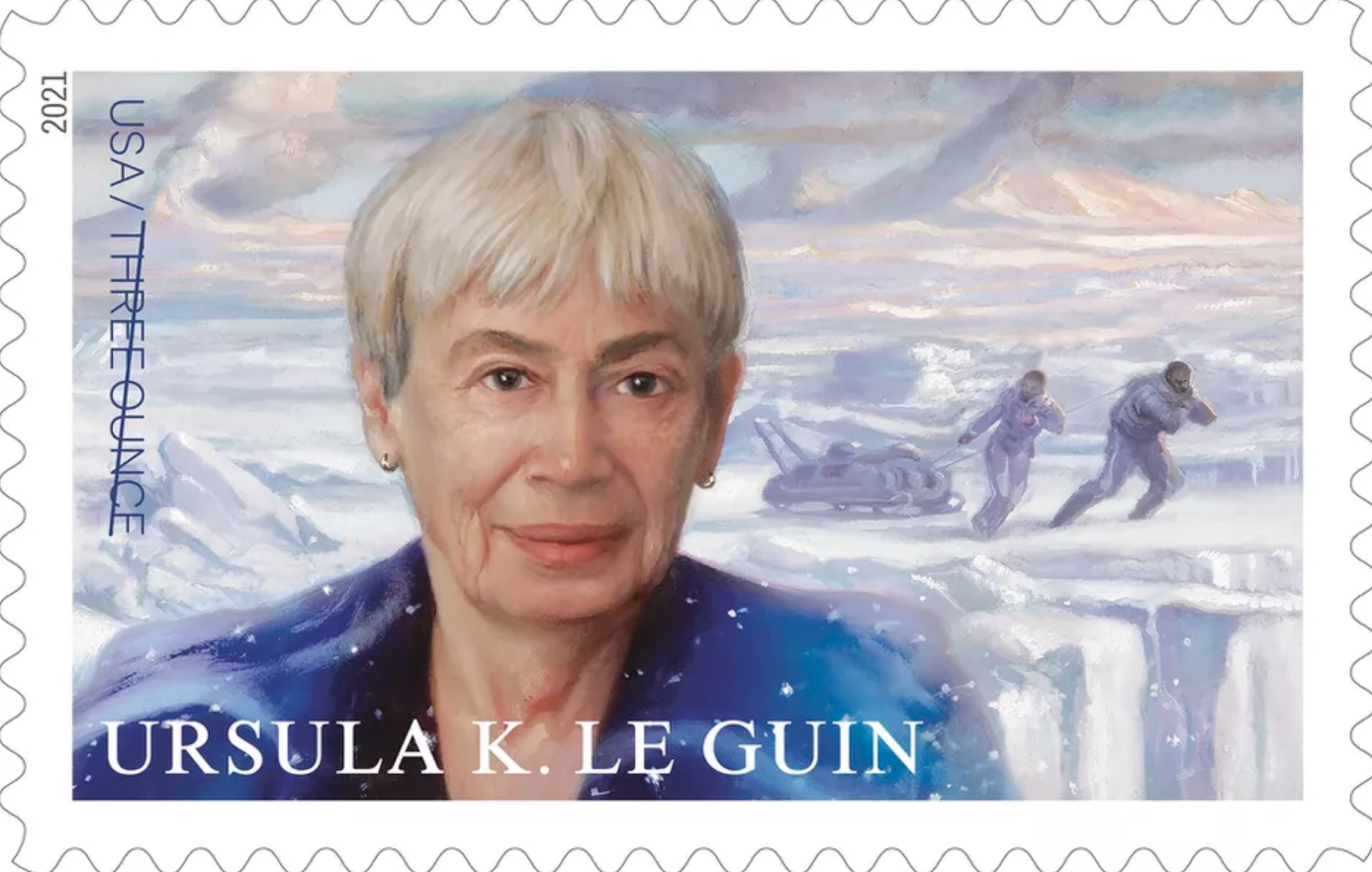

| 9:07p | Ursula K. Le Guin Stamp Getting Released by the US Postal Service

Here’s one thing that’s going right with America’s decaying postal system. They write on the USPS web site: “The 33rd stamp in the Literary Arts series honors Ursula K. Le Guin (1929-2018), who expanded the scope of literature through novels and short stories that increased critical and popular appreciation of science fiction and fantasy. The stamp features a portrait of Le Guin based on a 2006 photograph. The background shows a scene from her landmark 1969 novel “The Left Hand of Darkness,” in which an envoy from Earth named Genly Ai escapes from a prison camp across the wintry planet of Gethen with Estraven, a disgraced Gethenian politician. The artist for this stamp was Donato Giancola. The art director was Antonio Alcalá. The words “three ounce” on this stamp indicate its usage value. Like a Forever stamp, this stamp will always be valid for the value printed on it.” The postal service has not said precisely when the stamp will be released. Would you like to support the mission of Open Culture? Please consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. Also consider following Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and sharing intelligent media with your friends. Or sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. Related Content: Ursula K. Le Guin’s Daily Routine: The Discipline That Fueled Her Imagination When Ursula K. Le Guin & Philip K. Dick Went to High School Together Ursula K. Le Guin Names the Books She Likes and Wants You to Read Ursula K. Le Guin Stamp Getting Released by the US Postal Service is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/01/19 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |