[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, February 3rd, 2021

- “Catch a Movie About Time Loops” by Noel Murray (This came out after we recorded, so we missed out on Source Code and Final Girls.)

- “From Groundhog Day to Russian Doll, the Inescapable Power of the Time Loop” by Jen Chaney

- “Time-Loop Stories Are About Being Stuck, but the Genre Keeps Moving Forward” by Karen Han

- “How the ‘Palm Springs’ Team Found a New Wrinkle in the Time-Loop Movie” by Jake Kring-Schreifels

- “What the Ambiguous Ending of Netflix’s ‘Russian Doll’ Means for the Show” by Esther Zuckerman (Yes, there is a season 2 coming out this year)

- “Behind the Scenes of New Short Film, ‘Two Distant Strangers,’ About Police Killings in America” by Degen Pener

| Time | Event |

| 4:29a | Do We Need Yet More Films About Time Loops? A Pretty Much Pop Discussion (#80) of Groundhog Day and its Descendents

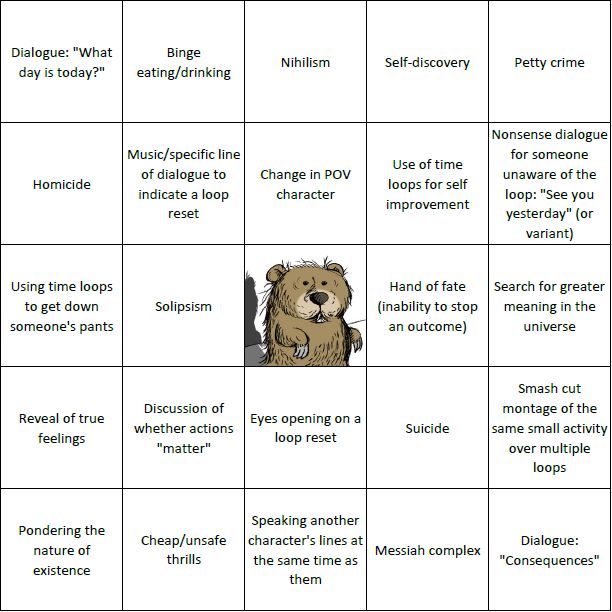

Tine looping, where a character is doomed to repeat the same day (or hour, or longer period) is a sci-fi trope dating back more than a century, but really entered American consciousness with the 1993 Bill Murray film Groundhog Day. Since then, and especially in the last five years, there have been numerous iterations of this idea in various genres from racial police-shooting drama to teen sex comedy. But do we need more of this? What are the philosophical ideas involved, and how do these change with tweaks to the scenario? Mark, Erica, Brian, and returning guest Ken Gerber discuss not only the very recent and popular forays into this genre with Hulu’s Palm Springs and Netflix’s Russian Doll, but also touch on Edge of Tomorrow, Repeaters, 12:01 PM, Before I Fall, The Fare, and episodes of The Twilight Zone, Star Trek: Discovery, The X-Files, and Rick & Morty. There are of course other film and TV uses of this trope. For a relatively full list, you can see this wiki page listing time loop films and this other wiki page discussing literary antecedents. Also see the “Groundhog Day” Loop page on tvtropes.org, and here’s a relevant reddit thread. Here are more articles: Watch the 12:01 PM 1990 short film. This bonus episode of the 11.22.63 podcast had a great discussion of time loop media including the Ken Grimwood novel Replay and the short story “12:01 P.M.” and its sequels. You can read the 1941 Malcolm Jameson story “Doubled and Redoubled” online. As a forerunner to the time loop idea, check out the very short 1892 children’s story “Christmas Every Day” by William Dean Howells, where time does move forward with its consequences, but it’s always Christmas! We talked a little about Happy Death Day with its costume designer in our ep. 38 and got into time travel more generally with Ken in ep. 22 and into “weird situations” in our Twilight Zone ep. 52. You may also enjoy Wes Alwan’s (sub)Text podcast discussing the psychological implications of Groundhog Day. Check out the time loop movie bingo card that Brian put together (with groundhog picture by Ken): Hear more of this podcast at prettymuchpop.com. This episode includes bonus discussion that you can access by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts.

Do We Need Yet More Films About Time Loops? A Pretty Much Pop Discussion (#80) of Groundhog Day and its Descendents is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 9:00a | The Bauhaus Chess Set Where the Form of the Pieces Artfully Show Their Function (1922)

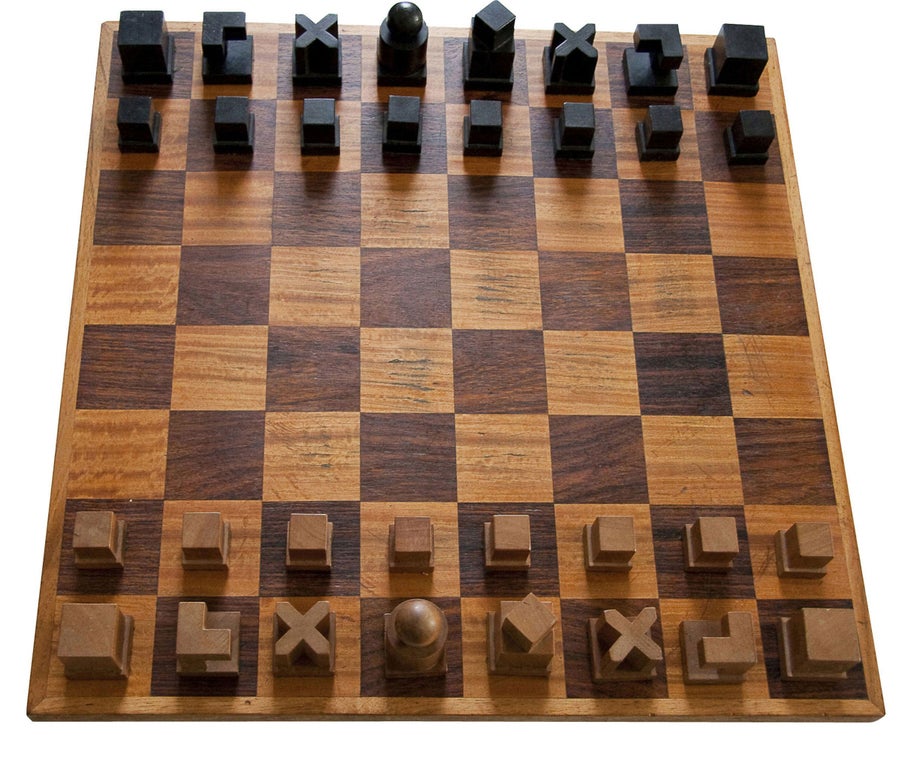

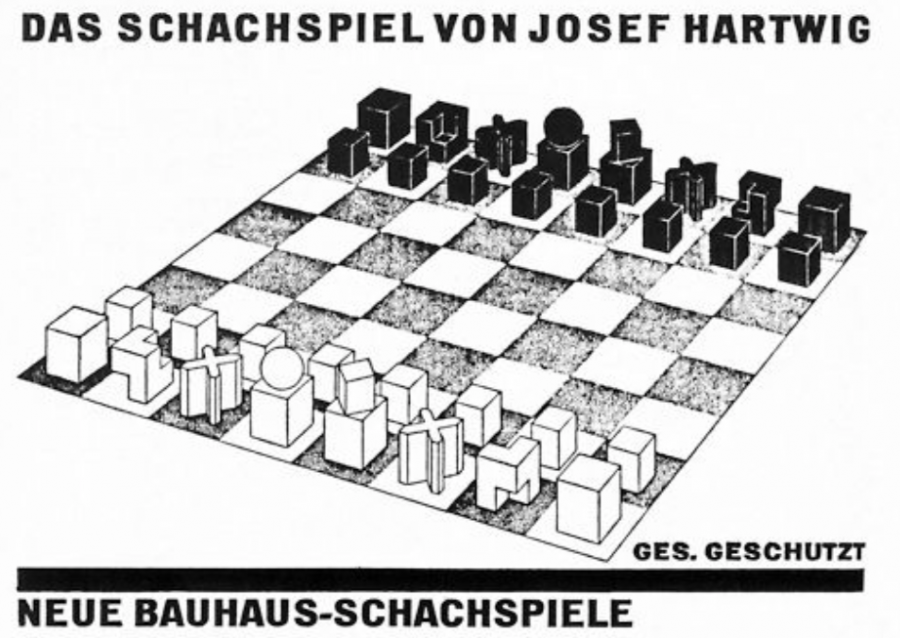

Learning to play chess first necessitates learning how each piece moves. This is hardly the labor of Hercules, to be sure, though it does come down to pure memorization, unaided by any verbal or visual cues. Does the name “pawn,” after all, sound particularly like something that can only step forward? And what about the shape of the knight suggests the shape of the knight’s move? The form of a chess piece, in other words, doesn’t follow its function — and under certain sets of aesthetic principles, there could be few greater crimes. Leave it to a member of the Bauhaus, the art school and movement that aimed to unify not just form and function but art, craft, and design — to bring them all into line. Brought into the Bauhaus in 1921 by its founder Walter Gropius, the sculptor Josef Hartwig began work on his redesigned chess set the following year. In all its iterations, the pieces takes on forms made of simple shapes: “The sphere, double cube, and three sizes of block, singly or combined, yield pieces that, despite their highly geometric stylization, are strongly suggestive of their rank or power,” says the Metropolitan Museum of Art, owner of one of one of Hartwig’s original sets. “The bishops are clearly implied by the cross outline, and the rooks by the simple stability of a cube. Most ingenious of all are the knights, formed of three double cubes joined in such a fashion that each face of the resulting form shows two cubes one above the other and a third on the side, an embodiment of the knight’s move.” Like many Bauhaus works, Hartwig’s chess set found a dual existence as both a piece of art and a consumer good. The artist himself also “made a poster to talk about his product” and “a box to package it,” says cuator Anne Monier in the video above, “so we really are in a total creation around a game of chess.” In addition to making the game’s movements easier to learn, it also constitutes a visual demonstration of what it means for form to follow function. The idea, says Monier, is “to spread the ideas of the Bauhaus in people’s everyday life, to be able in fact to change the living environment, to take part in creating a new society.” The video comes from Bauhaus Movement, an online shop where you can invite the spread into your home by ordering a replica Hartwig chess set. It’ll set you back €495, but ideals, now as in the heyday of the Bauhaus, don’t come cheap.

Related Content: Harvard Puts Online a Huge Collection of Bauhaus Art Objects The Politics & Philosophy of the Bauhaus Design Movement: A Short Introduction Marcel Duchamp, Chess Enthusiast, Created an Art Deco Chess Set That’s Now Available via 3D Printer Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The Bauhaus Chess Set Where the Form of the Pieces Artfully Show Their Function (1922) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

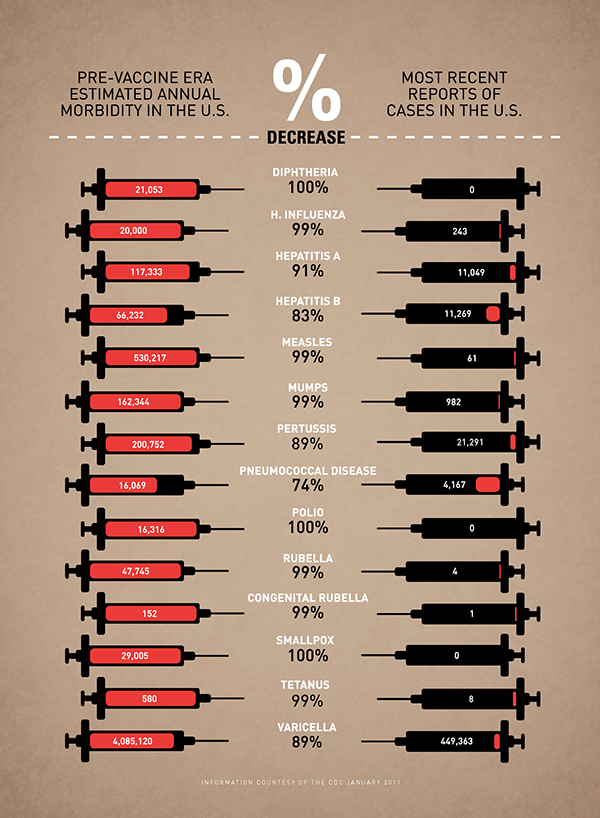

| 12:00p | How Vaccines Improved Our World In One Graphic

In 1796, the British doctor Edward Jenner developed the first vaccine to fight a contagious disease–in this particular case, the smallpox virus. Since then vaccines have helped eradicate, or firmly control, a long list of diseases–everything from diphtheria and the measles, to rubella and polio. Designed by Leon Farrant in 2011, the infographic above reminds us of the miracles brought by vaccines, showing the degree to which they’ve tamed 14 crippling diseases. Before too long, we hope COVID-19 will be added to the list. For the data used to make the graphic, visit this document online. Would you like to support the mission of Open Culture? Please consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. Also consider following Open Culture on Facebook and Twitter and sharing intelligent media with your friends. Or sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox. Related Content: How Do Vaccines (Including the COVID-19 Vaccines) Work?: Watch Animated Introductions 19th Century Maps Visualize Measles in America Before the Miracle of Vaccines How Fast Can a Vaccine Be Made?: An Animated Introduction How Vaccines Improved Our World In One Graphic is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | The Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson & Beatles Producer George Martin Break Down “God Only Knows,” the “Greatest Song Ever Written” As an Englishman of a certain age, George Martin could, realistically, choose only one means of conveyance in Los Angeles: a red Coupe de Ville convertible, and a genuine 1950s model at that. But whatever that era’s glories of automobile design, its music was still in the dark ages — at least according to the millions upon millions of Beatles fans around the world today. The pop-cultural revolution that band ignited in the early 1960s owes, by some reckonings, as much to Martin’s work as it does to that of the Fab Four themselves. In his capacity as a producer and arranger — not to mention as the man who signed them to Parlophone records — Martin arguably led the Beatles to discover their own musical potential. And once they’d become a phenomenon, they also felt pressure to surpass themselves from other sources. One was a young American singing group called the Beach Boys, who in less than five years had gone from putting out simple, repetitive tunes about surfing and root beer to crafting the teenage-symphonic masterpiece Pet Sounds. That album, so pop-music history tells it, picked up the gauntlet thrown down by the Beatles’ Rubber Soul, and in response to it came Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, an era-defining release since popularly thought to have won the bands’ friendly competition. But with his ear for composition, Martin surely knew that Pet Sounds would never truly be defeated, thanks in large part to “God Only Knows,” which Martin describes as “one of my favorite Beach Boys songs.” He does so in the clip at the top of the post, of a 1997 visit to Los Angeles in which he pilots his Cadillac to the home of the group’s musical mastermind Brian Wilson. The two then enter the studio and pull out the original master tapes of “Got Only Knows” to listen to its components one by one. You can see and hear more of what went into its recording sessions through this two–part video from Behind the Sounds that presents raw tracks from the studio with notes on the various techniques and players (including the famous “Wrecking Crew,” with bassist Carol Kaye) involved. “What Brian had done was to write a beautiful song full of unusual changes,” says Martin, “and then devise a tapestry of sounds to enhance it.” As Martin rebuilds the tracks on the console, Wilson says he’s “making a better mix of this than I did in the master.” It’s quite a compliment, considering the source — but then so is the declaration of “God Only Knows “as “the greatest song ever written,” issued as it was by a certain Paul McCartney. Related Content: How the Beach Boys Created Their Pop Masterpieces: “Good Vibrations,” Pet Sounds, and More Hear the Unique, Original Compositions of George Martin, Beloved Beatles Producer (RIP) George Martin, Legendary Beatles Producer, Shows How to Mix the Perfect Song Dry Martini Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson & Beatles Producer George Martin Break Down “God Only Knows,” the “Greatest Song Ever Written” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/02/03 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |