[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, February 4th, 2021

| Time | Event |

| 12:00p | Life Lessons From 100-Year-Olds: Timeless Advice in a Short Film

After his retirement at age 38, renaissance essayist Michel de Montaigne devoted several pages to the subject of mortality, as pressing an issue for him as for the classical philosophers he adored. And no less pressing an issue for us, of course. The brute fact of death aside, the quality of our lives has little in common with those of Cato, Seneca, or Montaigne himself. We meet needs and wants with commands to Alexa. We are beset by global anxieties they never imagined, and by remedies that would have saved millions in their time. Even in the age of Covid-19, life isn’t nearly so precarious as it was in 16th century France. But whether we set the threshold at 40, 80, or 100, “to die of old age is a death rare, extraordinary, and singular,” Montaigne argued. Few attain it today. “It is the last and extremest sort of dying… the boundary of life beyond which we are not to pass, and which the law of nature has pitched for a limit not to be exceeded.” For these reasons and more, we look to the very aged for wisdom: they have attained what most of us will not, and can only look backwards, seeing the fullness of life, if they have clarity, in panoramic hindsight. Such vision is the subject of the 2016 short film above, in which three uniquely lucid centenarians dispense advice, reflect on their experience, and reminisce about the jazz age. “I have always been lucky,” says now-108-year-old Tereza Harper. “I’ve never been unlucky.” No one lives to such an advanced age without facing a little hardship. Harper immigrated to England from Czechoslovakia during World War II to reunite with her father, who had been a prisoner of war. She lived to witness the many horrors of the 20th century and the many of the 21st so far. And yet, she says, “Everything makes me happy. I love talking to people. I like doing things. I like going out shopping. Once I go out shopping, I don’t really want to come back…. I’m not going yet. I’m still strong. I’m very very strong. I never realized how strong I am.” ” What is the source of such strength and joy in the ordinary repetitions of daily life? A profound contentment marked by a sense of completion, for one thing. “I don’t think there’s anything that I really need to do,” Harper says, “because I’ve done practically everything that I’ve ever wanted to do in the past.” Likewise, 101-year-old Cliff Crozier, who died last year, remarks, “I think I’ve done all that I wanted to do.” Later, he adds some nuance: “I don’t have many failures,” he says. “If I’m making a cake and it fails it becomes a pudding.” (He also says, “It always pleases me that I can keep robbing the government with my pension.”) Are there regrets? Naturally. 102-year-old John Denerley, who passed away in 2018, says ruefully, “If I’d have been more attentive at school in my early life, I’d have studied more, and harder…. Well, I didn’t do too bad in the end. But I think the sooner you start studying the better.” Crozier expresses regrets over the way he treated his father, a relationship that still causes him grief. These three are not, after all, superhumans. They are subject to the same pains as the rest of us. But they have achieved a vantage from which to see the whole of life from its limit. Whether or not we achieve the same, we can all learn from them how to make the most of the “extraordinary fortune,” as Montaigne wrote, “which has hitherto kept us above ground.” Related Content: Ram Dass (RIP) Offers Wisdom on Confronting Aging and Dying Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Life Lessons From 100-Year-Olds: Timeless Advice in a Short Film is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

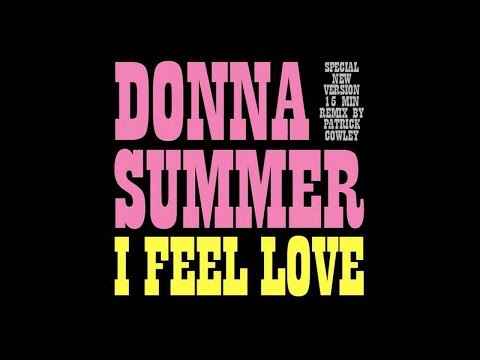

| 3:00p | How Giorgio Moroder & Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” Created the “Blueprint for All Electronic Dance Music Today” (1977) House, trance, techno—any DJ playing a four-on-the-floor groove can drop Donna Summer and Giorgio Moroder’s “I Feel Love” into a set and instantly mesmerize the crowd. It has been happening since 1977. The disco hit doesn’t just hold up as a classic moment of nostalgia: it’s still one of the greatest dance tracks ever produced. “‘I Feel Love’ was and remains an astonishing achievement,” Jon Savage writes at The Guardian. “A futuristic record that still sounds fantastic 35 years on. Within its modulations and pulses, it achieves the perfect state of grace that is the ambition of every dance record: it obliterates the tyranny of the clock.” DJ Jim Stanton puts it this way: “It is safe to say [‘I Feel Love’] was the blueprint for all electronic dance music today. It still has a massive impact every time I play it.” The song was not only a “radical breakthrough” at the time but it was explicitly meant to be one, an experimental studio collaboration between Moroder, Pete Bellotte, drummer Keith Forsey, and engineer Robby Wedel, who was classical composer Eberhard Schoener’s assistant and was hired because he was the only one who knew how to work Schoener’s borrowed Moog Modular 3P. Wedel cooked up the bassline and Moroder and Bellotte pieced the track together from twenty to thirty-second snippets, since the Moog “would go out of tune every few minutes,” Moroder remembered. “It was quite a job.” Bellotte and Summer wrote the lyrics and Summer, fresh off an important call with her astrologer about her love life, “turned up to the studio,” Bill Brewster writes at Mixmag, “and delivered the song in one take.” Upon hearing “I Feel Love” on its release, during the Berlin sessions for David Bowie’s Low, no less a shaper of the future than Brian Eno immediately realized its potential, running into the studio to proclaim, “I have heard the sound of the future. This is it, look no further. This single is going to change the sound of club music for the next fifteen years.” He was not wrong. “Until ‘I Feel Love,’” Brewster writes, “synthesizers had either been the province of serious musicians like Keith Emerson, Jean-Michel Jarre or Tangerine Dream or used as a novelty prop in throwaway songs.” They had gained respect in the classical world, thanks to Wendy Carlos’ Switched on Bach, and by the late seventies they popped up in the mix of rock and funk often. Moroder’s creation, however, put the instrument at the center of a dance track for the first time. “‘I Feel Love’ was a rejection of the intellectualization of the synthesizer in favour of pure pleasure.” The song killed on Soul Train and “went to No 1 in the UK during the high summer of 1977, and stayed there for four weeks—filling dance floors everywhere,” writes Savage. “Like David Bowie’s Low and Heroes, and Kraftwerk’s Trans-Europe Express, it was also the secret vice of those punks who were already tiring of sped-up pub rock, and it sowed the seeds for the next generation of UK electronica.” It didn’t chart in the U.S. but became “an all-time gay classic,” and hence a staple of the pre-A.I.D.S. house music era. Remixes appeared immediately, including Patrick Cowley’s psychedelic 15-minute version, “which really does go on for ever and ever without trashing—even enhancing—the concept of the original.” Indeed, “I Feel Love” is as near a pure archetype of the dance track as we’re ever going to find, so timeless it obliterates time, stretching out to 30 minutes in the “Disco Purrfection” version below, the first song to “fully utilize the potential of electronics, replacing lush disco orchestration with the hypnotic precision of machines,” and ushering in the age of New Order, Depeche Mode, and countless classic house and techno records from Chicago, New York, and Detroit, none of which hold up as well Moroder and Summer’s slick, sultry “I Feel Love.” Related Content: A Soul Train-Style Detroit Dance Show Gets Down to Kraftwerk’s “Numbers” in the Late 80s Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How Giorgio Moroder & Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” Created the “Blueprint for All Electronic Dance Music Today” (1977) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00p | All 80 Issues of the Influential Zine Punk Planet Are Now Online & Ready for Download at the Internet Archive

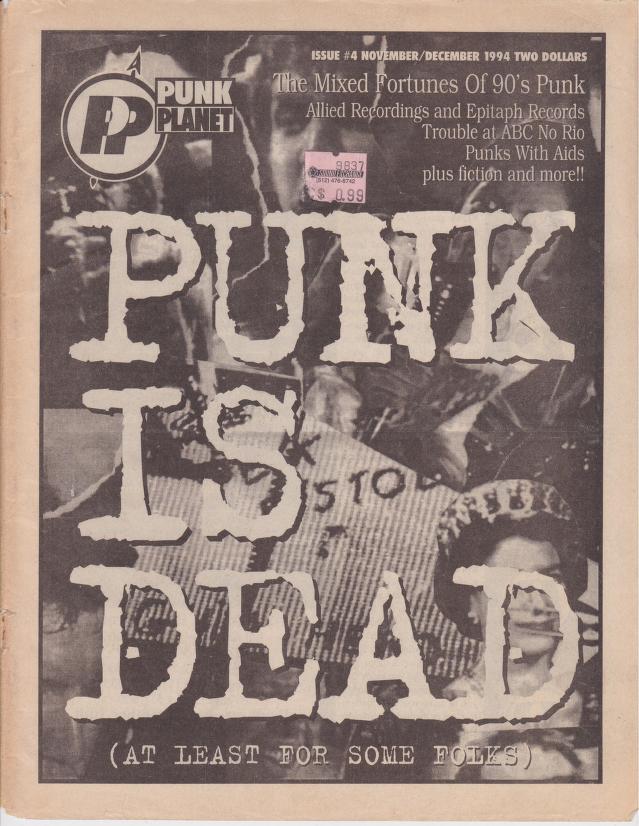

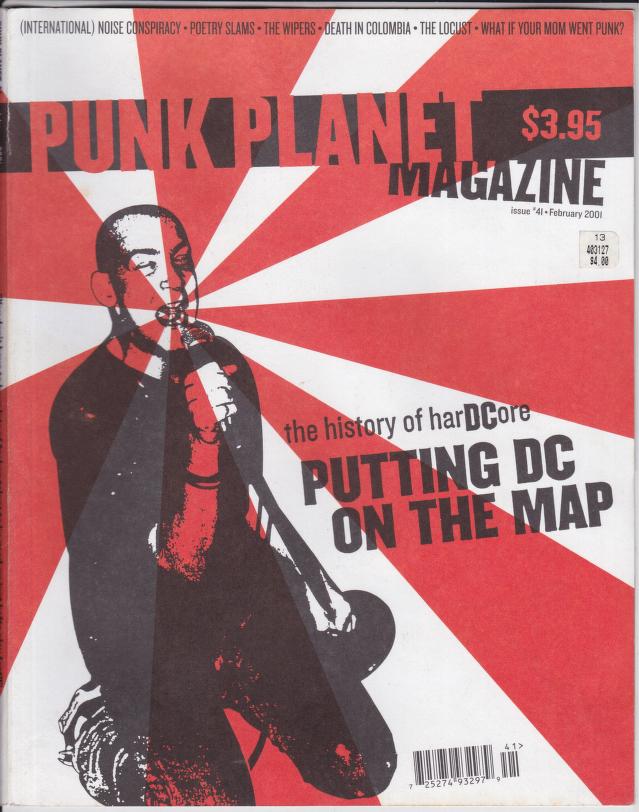

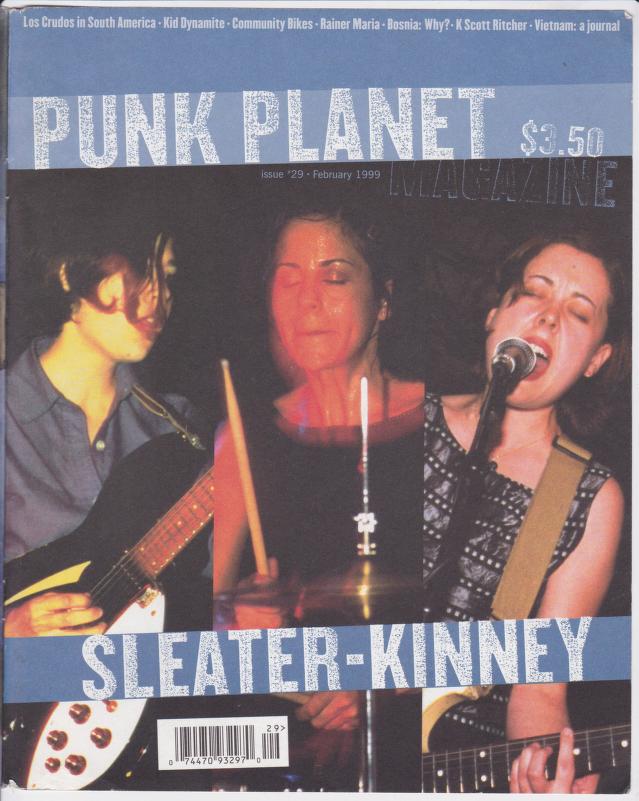

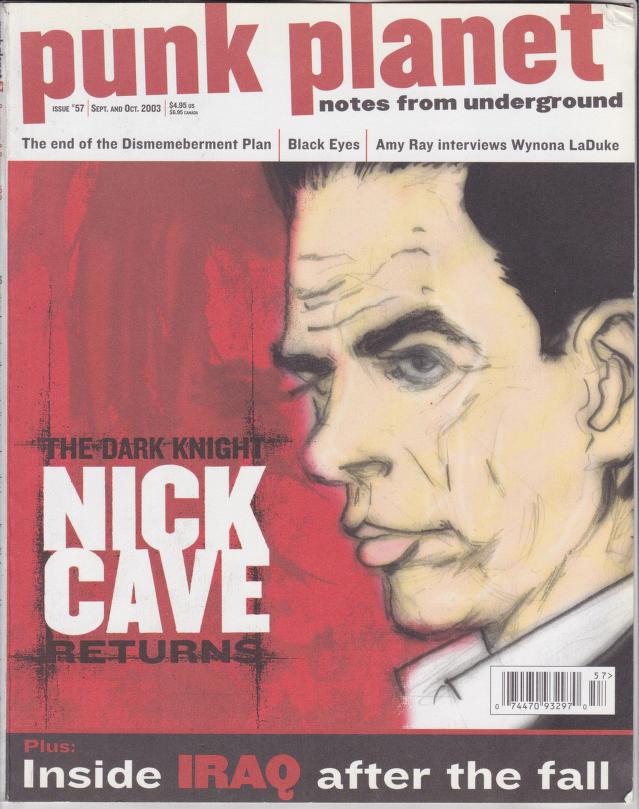

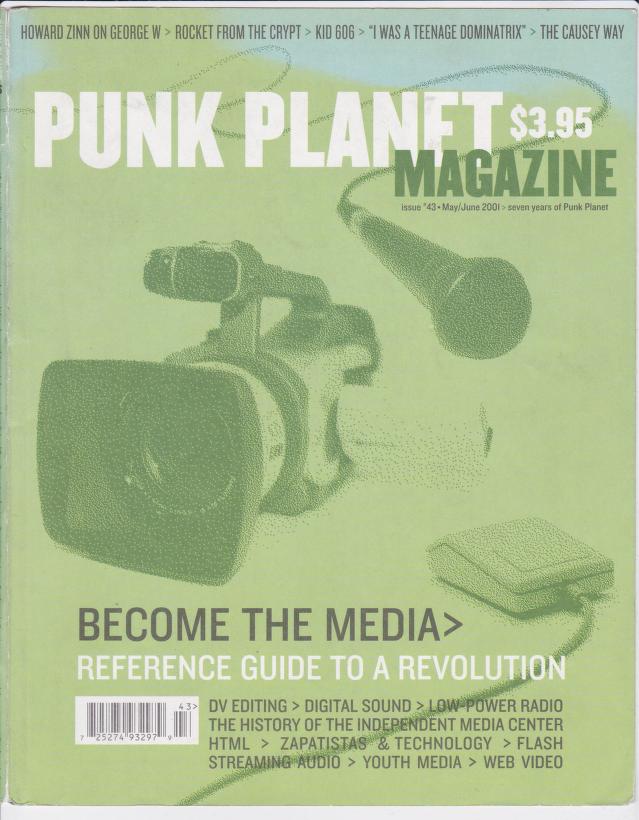

Punk didn’t die, it evolved, since its inception in the 70s to the ethos of majorly influential figures like Kathleen Hanna and Ian MacKaye in the 90s, two of the most prominent faces of progressive DIY punk in the U.S. Then, as before, scenes came together around zines, sites of cultural recognition, dissemination, and recording for posterity in the archives of physical print. One zine critical to the socially conscious punk that emerged at the time, Punk Planet, has recently been digitized in all 80 issues by the Internet Archive.

Based in Chicago and founded by editor Dan Sinker (whom you may know from his presence on Twitter), Punk Planet ran from 1994 to 2007, focusing “most of its energy on looking at punk subculture,” the Internet Archive writes, “rather than punk as simply another genre of music to which teenagers listen. In addition to covering music, Punk Planet also covered visual arts and a wide variety of progressive issues—including media criticism, feminism, and labor issues.”

Punk Planet “transcended stereotypes to chronicle the progressive underground community, from thoughtful band interviews to exceptionally thorough investigative features,” wrote the A.V. Club’s Kyle Ryan in an interview with Sinker the year of the magazine’s demise. “Over the course of 13 years, Punk Planet became heavily influential beyond the increasingly small world of independent publishing.” Arguably, that influence can be felt in online magazines like Rookie as well as music-focused stalwarts like Pitchfork, who note that Punk Planet’s “issues included interviews with Sleater-Kinney, Nick Cave, Ralph Nader, and countless other cultural icons.”

The magazine folded for the usual reasons, as Utne noted in a farewell, leaving a “gaping hole in the landscape of independent magazines…. The deck was stacked against Punk Planet, though, and the hard knocks of independent publishing finally became too much to bear.” Sinker says he saw the end as part of a bigger picture and “started looking at the larger issues that were also affecting us. Things like, ‘Hey, wow, record labels are going under because no one is paying for music!’ And, ‘Hey, look at this, people are going to these Internet sites because people can pick up a record review the same day the record came out!’”

It’s a moot point now—2020 has not made it any easier for small publications and independent musicians to survive. But the continued existence of Punk Planet online for new generations to discover promises to foster the continuity that carried the spirit of punk rock through decades of evolutionary change. Enter the Punk Planet archive here. Related Content: Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness All 80 Issues of the Influential Zine Punk Planet Are Now Online & Ready for Download at the Internet Archive is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/02/04 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |