[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, February 11th, 2021

- “Audio and Podcasting Fact Sheet” from journalism.org

- “Podcast vs Radio: What Is the Difference?” from Buzzsprout

- “New Podcast Listeners Are Coming from Radio, Not Music” by Bill Rosenblatt

- “Is Radio Dying?” by Katherine Luck

| Time | Event |

| 2:53a | Monkey Sees A Magic Trick Happy Wednesday…. h/t Allie Monkey Sees A Magic Trick is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:01a | Radio vs. Podcasting: A Discussion with Jason Bentley (KCRW, The Backstory) on Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #81

Jason was music director at KRCW, the LA NPR station, is also a DJ with a lot of experienced interviewing musicians, and now hosts a new podcast, The Backstory. He joins Mark and Erica to discuss the creative and business possibilities of podcasting in comparison to radio, what their futures may hold, and his own journey between the two media. Follow Jason @thejasonbentley. Listen to his Backstory interview with Kristen Bell and his current radio show, Metropolis. Here’s some comparison data and other basic information on radio and podcasts: Hear more of this podcast at prettymuchpop.com. This episode includes bonus discussion that you can access by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts. Radio vs. Podcasting: A Discussion with Jason Bentley (KCRW, The Backstory) on Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #81 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

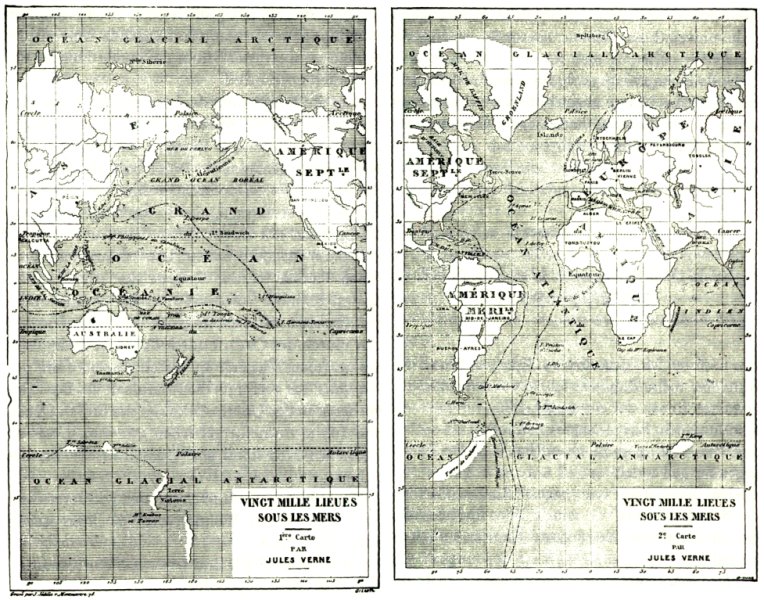

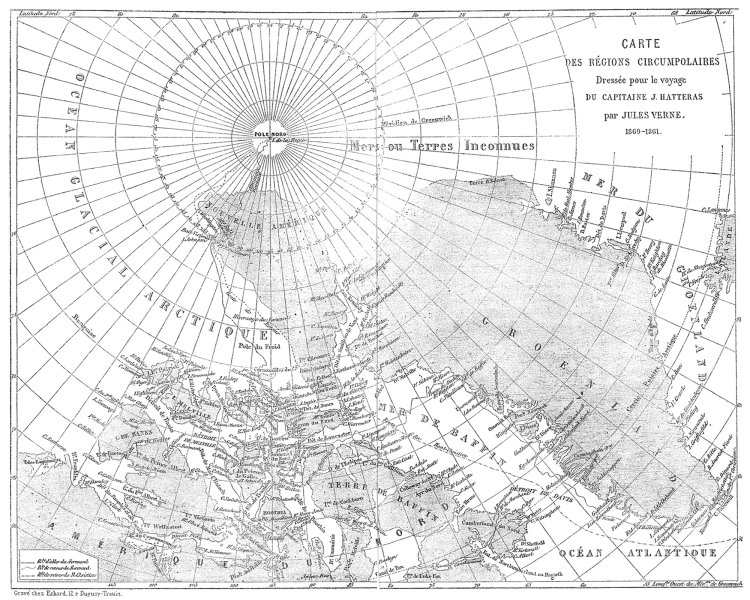

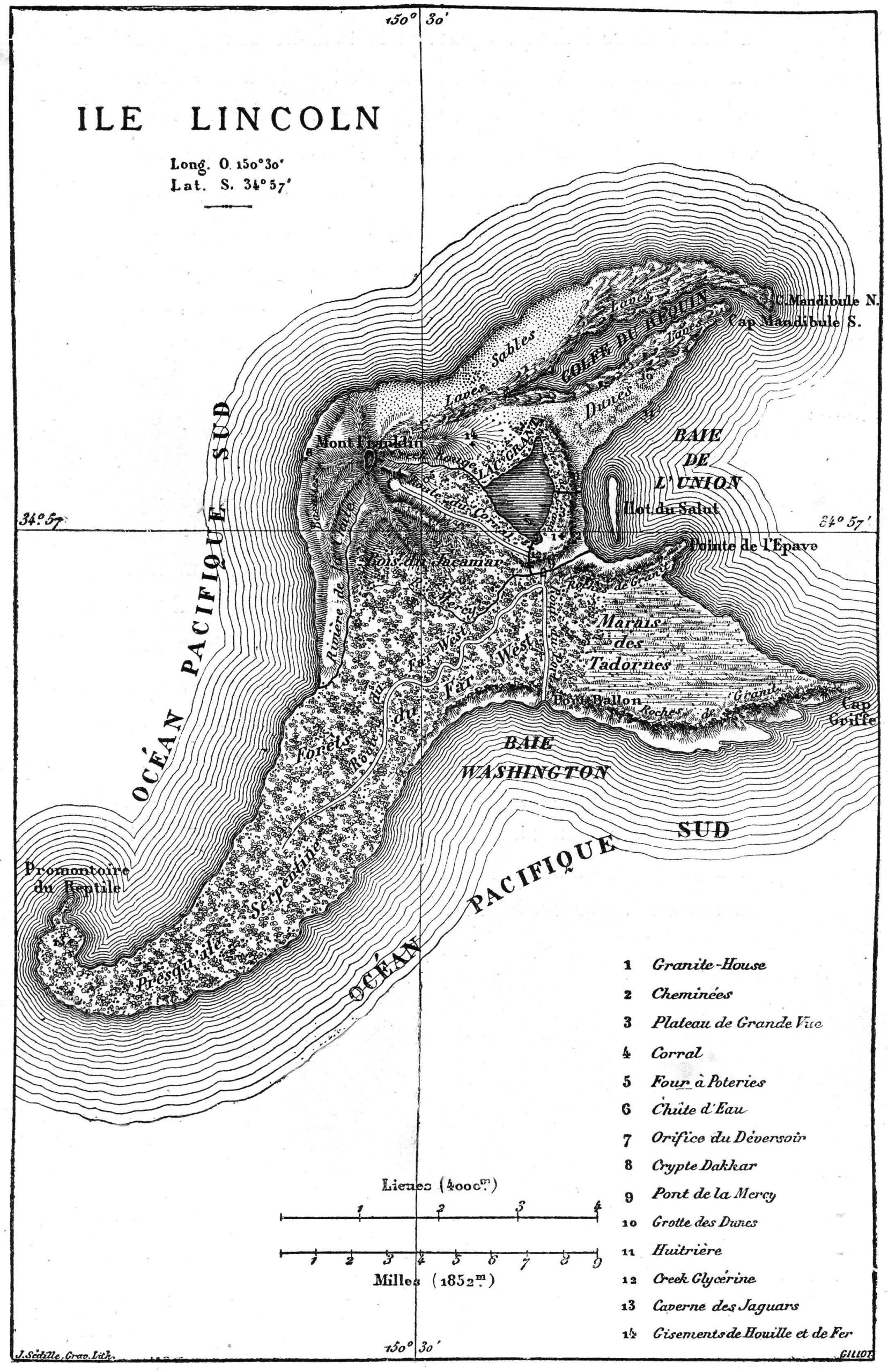

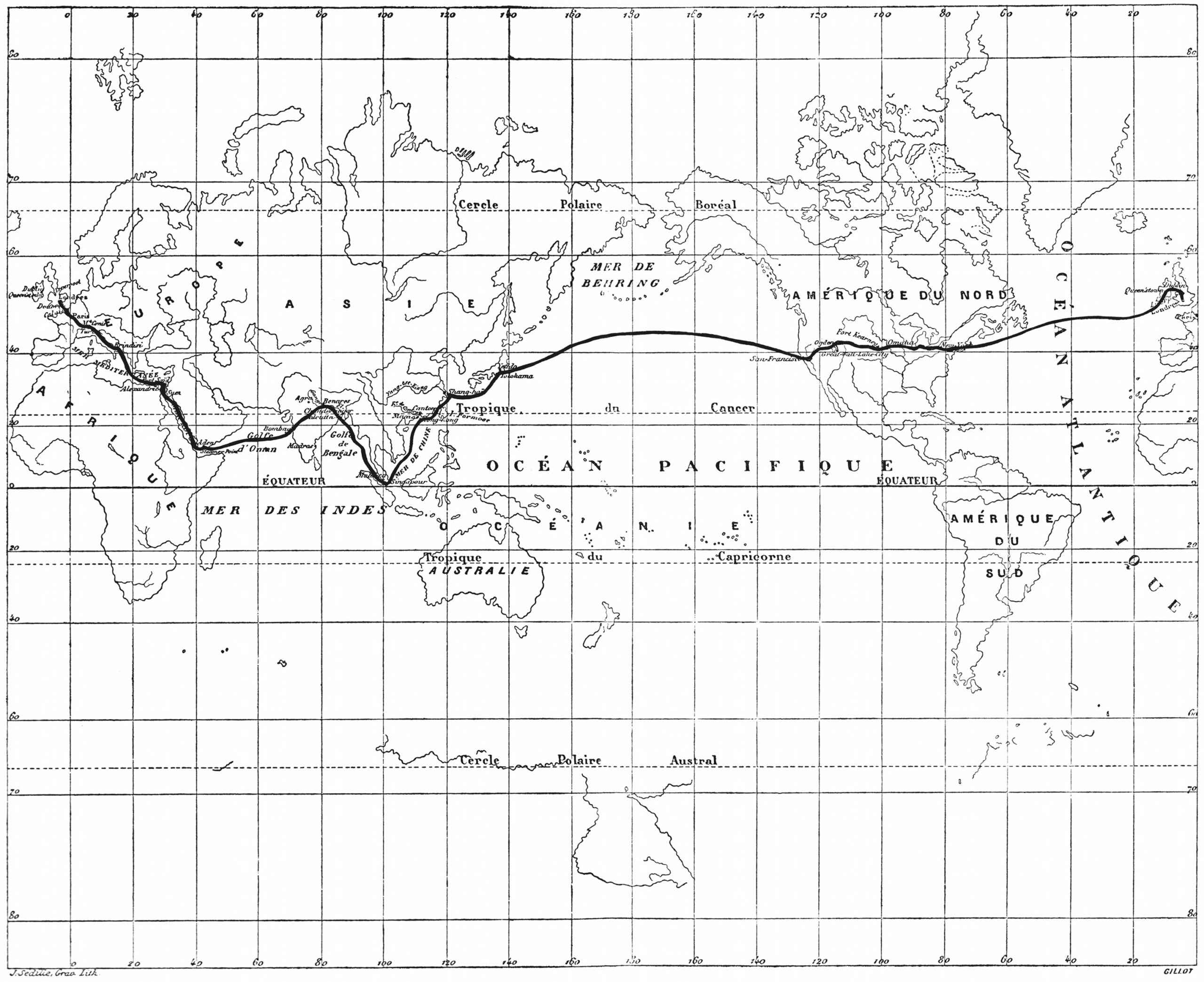

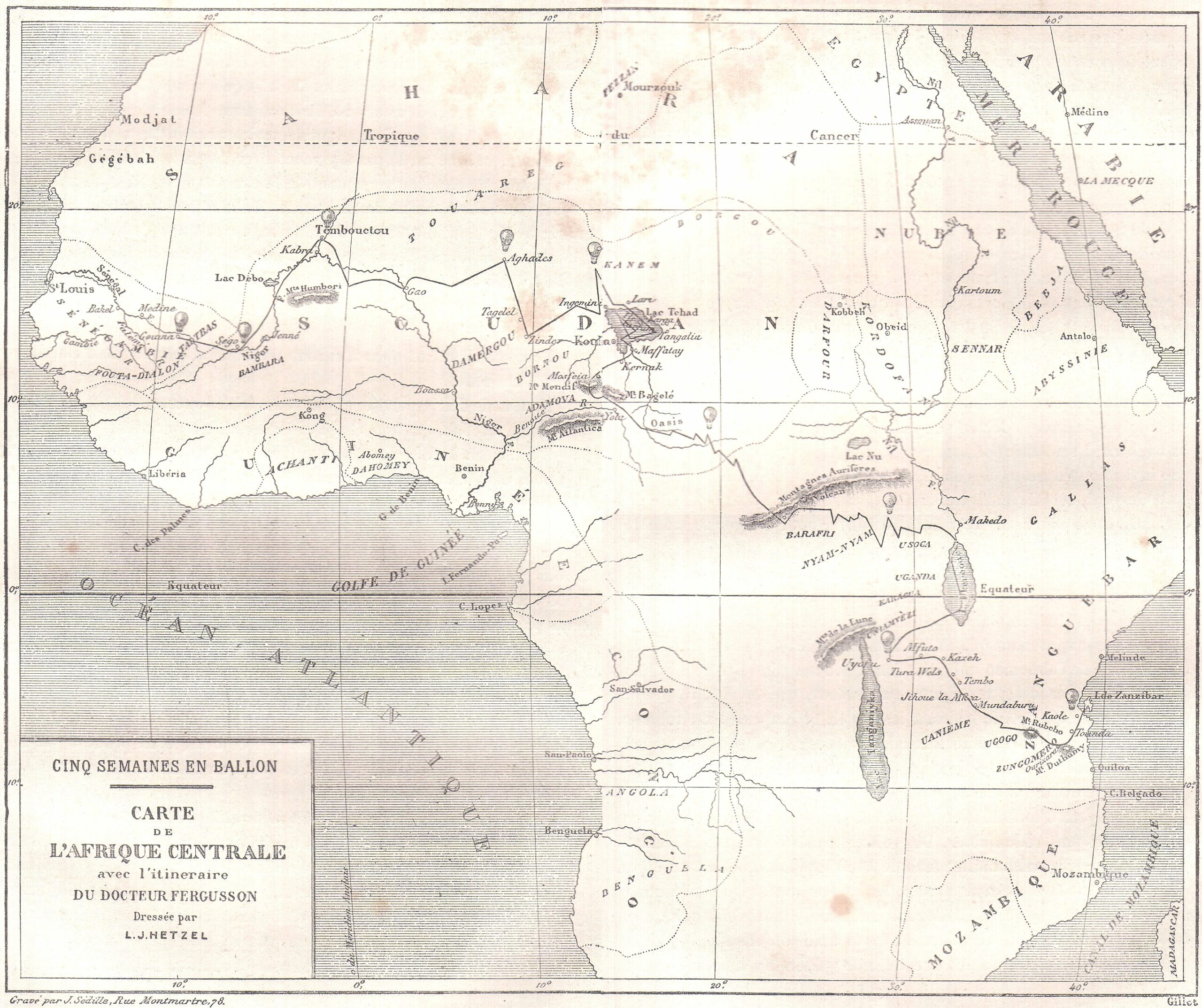

| 9:00a | Behold All 42 Maps from Jules Verne’s Extraordinary Voyages, the Author’s 54-Volume Collection of “Geographical Fictions”

Jules Verne’s tales of adventure take his characters around the world, through the deepest seas, even into the center of the Earth—on journeys, that is, difficult or impossible in the 19th century. Verne himself, however, spent most his life in France, writing of places he had not seen. In one apocryphal story, the young Jules Verne is caught trying to sneak aboard a ship bound for the Indies and promises his father he will henceforth travel “only in his imagination.” Whether or not he made such a vow, he seemed to keep it, though the idea that he never traveled at all is a “tiresome canard,” writes Terry Harpold in an essay titled “Verne’s Cartographies.” Verne’s famed novels Twenty Leagues Under the Sea, Journey to the Center of the Earth, and Around the World in Eighty Days constitute only a fraction of the 54-volume Voyages Extraordinaires, a collection of fiction conceived on the basis of a science we might not think of as a rich field for material. “Of the 80 novels and other short stories he published,” geographer Lionel Dupuy writes, “62 make up the corpus of Extraordinary Voyages (Voyages Extraordinaires). These books, in which imagination played a vital role, were termed ‘geographical novels,’ a category the author himself used for them.”

Verne would also use the term “scientific novel,” but he made it clear which science he meant:

As a geographical novelist, and member of the Geographical Society from 1865 to 1898, it was only fitting that Verne include as many maps as he could in his quest, as he put it, “to depict the Earth, and not just the Earth, but the universe, for I have sometimes carried my readers far away from the Earth in my novels.” To that end, “thirty of the novels” in the first edition of Voyages Extraordinaires” published by Pierre-Jules Hetzel, “include one or more engraved maps,” Harpold points out. “There are forty-two such engravings in all.” View them here.

“These images and design elements are nuanced, graceful, and evocative; drafted and engraved by some of the finest artists of the time,” Harpold writes. “They represent the pinnacle of late nineteenth-century popular-scientific cartography.” They also represent the author of geographical fictions who, as both a scientist and artist, refused to let either form of thinking take over the text, combining myth and poetry with observation and measurement. As Dupuy puts it, “in Extraordinary Voyages, the passage from reality to imagination and back is encouraged by the emergence of a ‘marvelous’ that we can call ‘geographical.’”

In one sense, we might think of most kinds of fiction as geographical, in that they describe places we have never seen. This is particularly so in fictions that include maps of their imagined territories, such as those of William Faulkner, J.R.R. Tolkien, Robert Louis Stevenson, and so on. We might look to Jules Verne as their towering forbear. “Several of the maps appearing in the Hetzel Voyages were drafted under Verne’s close supervision or were based on his sketches or designs. Maps in three of the novels (20,000 Leagues [top], Hatteras [further up], Three Russians) were drafted by Verne himself, whose talents in this regard were appreciable,” writes Harpold. Verne’s maps mix real and fictional place names and are “always ambiguous and semiotically unstable objects.” They appear almost as admissions of the mythmaking that goes into the science of geography and the act of exploration. Near the end of his life, maps became more real to Verne than the world outside. As he grew too weary even to leave the neighborhood, he wrote to Alexandre Dumas fils, “If I have maintained a taste for work… , nothing remains of my youth. I live in the heart of my province and never budge from it, even to go to Paris. I travel only by maps.” See all of Verne’s maps from the Hetzel edition of Extraordinary Voyages, such as those for Around the World in Eighty Days (above) and Five Weeks in a Balloon (below), here.

Related Content: William Faulkner Draws Maps of Yoknapatawpha County, the Fictional Home of His Great Novels Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Behold All 42 Maps from Jules Verne’s Extraordinary Voyages, the Author’s 54-Volume Collection of “Geographical Fictions” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 12:00p | A Tour of U.S. Accents: Bostonian, Philadelphese, Gullah Creole & Other Intriguing Dialects You don’t have an accent — or rather, everyone has an accent, but we don’t notice our own, especially if we associate mostly with people of similar cultural backgrounds. For however we might like to describe ourselves, the way we speak reveals who we are: as dialect coach Erik Singer puts it in the Wired video above, “Accent is identity.” Among the forces shaping that identity he names not just geography but socioeconomic background, generation, ethnicity and race, and other “individual factors.” The result is that a large and varied continent like North America has given rise to a wide variety of accents in the English language alone. In the video Singer and four other specialist language experts demonstrate a great many of these North American accents, identifying the most distinctive characteristics of each. The classic Boston accent, for example, is “non-rhotic,” referring to the dropping of “R” sounds that make possible such classic phrases as “pahk yah cah in Havahd Yard.” It differs in many ways from those common in places like Rhode Island and New York City, relatively close together though all three areas may seem: the diversity of accents on the U.S. east coast versus its more recently settled west coast underscores the fact that regional accents need time, usually a matter of generation upon generation, to emerge. The way Philadelphians talk illustrates what Singer calls “the ‘on’ line,” north of which most pronounce “on” as if it rhymes with “don,” and south of which — Philly and below — most pronounce “on” as if rhymes with “dawn.” You don’t even have to cross the Pennsylvania border to find another unique accent. Only in Pittsburgh do people “smooth the ‘mouth’ dipthong,” a dipthong being a syllable composed of two distinct vowels — here, the “ou” in “mouth” — the “smoothing out” of which turns it into a single (and to non-Pittsburghers, unusual-sounding) vowel. By the end of these 20 minutes, Singer and his crew have made it only as far as the “Piney Woods Belt” of the American south, whose accents bring to many of our minds the voice of Scarlett O’Hara and Blanche DuBois. They’ve also touched on such linguistic curiosities as Gullah creole; the Elizabethan inflection of Ocracoke Island, North Carolina,” previously featured here on Open Culture; and in some ways the most curious of all, the broadly designated “general American” speech that has emerged in recent decades. This is only the first video of a series, so keep an eye on Wired‘s Youtube channel for the next installment of the linguistic journey — and keep an ear out for all the subtle varieties of English you can catch in the meantime. Related Content: A Brief Tour of British & Irish Accents: 14 Ways to Speak English in 84 Seconds The Speech Accent Archive: The English Accents of People Who Speak 341 Different Languages Why Do People Talk Funny in Old Movies?, or The Origin of the Mid-Atlantic Accent Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. A Tour of U.S. Accents: Bostonian, Philadelphese, Gullah Creole & Other Intriguing Dialects is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 6:29p | Watch Prince Perform “Purple Rain” in the Rain in His Transcendent Super Bowl Half-Time Show (2007) Prince is having an afterlife the opposite of most rock stars. Where the years after death seems to bring our gods down to human size, the more stories I hear about Prince, the more I am convinced he was either beyond human or one of the very few constantly working at maximum potential. But not only that, he also helped others realize their own potential, especially members of his touring band. I hope that’s your takeaway after having watched not just this mini-doc of his 2007 Super Bowl HalfTime show, but reading this thoroughly entertaining oral history of the event from The Ringer. Even if football is not your thing, and you consider the halftime show to be cheesy, this one year was not. Prince considered it one of his crowning achievements, and it was going to be the end point of the memoirs he planned to write. Half-time shows had traditionally been the venue for marching bands and color guard, but by the 1990s they had turned into Hollywood productions, with pop stars and dancers. However, they had also been dealt a blow with Nipplegate, when Justin Timberlake ripped open Janet Jackson’s corset and exposed a metal pastie in 2004. Middle America reeled, people thought of the children, the FCC levied some fines, and the NFL went into defensive mode, programming the kind of Boomer-safe artists that would please as many people as possible: The Rolling Stones and Paul McCartney. (I mean, all amazing artists, mind you. Just nothing dangerous.) Prince was different. He wasn’t going to do this like an aging rock star, just come on out and play the hits. He could have done and he certainly had the back catalog to do so. Instead, he put together a show that could stand on its own, a mix of his hits and a wild selection of cover versions: Queen’s “We Will Rock You”, “Proud Mary”, Hendrix/Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower”, and the Foo Fighters’ “Best of You.” The day of the Super Bowl in Miami it rained, Florida-style. Monsoon weather. Yet, Prince and his band went ahead, defying the elements. The dancers—Maya and Nancy McClean—put grips on their high heel boots so as not to slip on the glass-like stage, formed in the shape of Prince’s “symbol”. There was an understandable panic: would somebody be electrocuted? Would this be Prince’s last concert? But no. Prince seemed to transcend the elements. Ruth Arzate, Prince’s personal assistant/manager asked the musician’s hairstylist: “Am I hallucinating or is there no rain on him?” You could see a couple of droplets on his shoulder. And we’re looking and she’s like, “It just looks like a fine mist on his face.”” Prince ended the concert with “Purple Rain,” which you can see above, singing *in the rain* and then busting out a solo for the ages behind billowing fabric as a shadow, wielding that symbol guitar like a glorious phallus. Halftime show production designer Bruce Rogers says it best: “To me, it’s about one guy in the middle of a hundred thousand people and a hundred million people on television, and it’s your moment to be Prince at the Super Bowl and Mother Nature is dropping thousands and thousands of gallons of rain. I always thought how cool the guy is to rise up and just get stormed upon, and just bring what he brought. That was so special.” There are several takeaways from the Ringer piece: how Prince would glide around on custom-made Heelys. How he would perform in meetings with a full band instead of just playing a CD. How when a cable accidentally got run over before the show a roadie literally held the stripped cable together for 20 or so minutes, running the risk of electrocution, to keep the show going. But my favorite takeaway is this quote, from Chicago Tribune’s Mark Caro: “He took this massively overscaled event and just sort of bent it to his will.” Super Bowl XLI became a Prince concert with a football game on either side of it, and that’s because he made it so. Related Content: Prince’s First Television Interview (1985) Prince Plays a Mind-Blowing Guitar Solo On “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here. Watch Prince Perform “Purple Rain” in the Rain in His Transcendent Super Bowl Half-Time Show (2007) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/02/11 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |