[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, March 30th, 2021

| Time | Event |

| 8:18a | How Bob Marley Came to Make Exodus, His Transcendent Album, After Surviving an Assassination Attempt in 1976 “The people who are trying to make this world worse aren’t taking a day off. How can I?,” said Bob Marley after a 1976 assassination attempt at his home in Jamaica in which Marley, his wife Rita, manager Don Taylor, and employee Louis Griffiths were all shot and, incredibly, all survived. Which people, exactly, did he mean? Was it Edward Seaga’s Jamaican Labour Party, whose hired gunmen supposedly carried out the attack? Was it, as some even conspiratorially alleged, Michael Manley’s People’s National Party, attempting to turn Marley into a martyr? Marley had, despite his efforts to the contrary, been closely identified with the PNP, and his performance at the Smile Jamaica Concert, scheduled for two days later, was widely seen as an endorsement of Manley’s politics. When he made his now-famously defiant statement from Island Records’ chief Chris Blackwell’s heavily guarded home, he had just decided to play the concert–this despite the continued risk of being gunned down in front of 80,000 people by the still-at-large killers, or someone else paid by the CIA, whom Taylor and Marley biographer Timothy White claim were ultimately behind the attack. Marley doesn’t just show up at the concert, he “gives the performance of his lifetime,” notes a brief history of the event, and “closes the show by lifting his shirt, exposing his bandaged bullet wounds to the crowd.” Erroneously reported dead in the press after the shooting, Marley emerged Lazarus-like, a Rastafarian folk-hero. Then he left Jamaica to make his career statement, Exodus, in London — as much a fusion of his righteous political fury, religious devotion, erotic celebration, and peace, love & unity vibes as it is a fusion of blues, rock, soul, funk, and even punk. It’s a very different album than what had come before in 1976’s Rastaman Vibrations, which was an album of “hard, direct politics” and righteous, “macho” anger, wrote Vivien Goldman, “with surprising specifics like ‘Rasta don’t work for no C.I.A.’” The apotheosis that was 1977’s Exodus begins, however, not with Marley’s previous album but with the Smile Jamaica concert. What was meant to be a brief, one-song, non-aligned appearance became after the shooting “a transcendental 90-minute set for a country being torn apart by internal strife and external meddling,” says Noah Lefevre in the Polyphonic video history at the top. “It was the last show Bob Marley would play in Jamaica for more than a year.” See the full Smile Jamaica concert above and learn in the Polyphonic video how “six months to the day” later, on June 3, 1977, Marley left on his own exodus and came to record and release what Time magazine named the “album of the century” — the record that would “transform him from a national icon to a global prophet.” On Exodus, he achieves a synthesis of global sounds in a defining creative statement of his major themes. Marley was “really trying to give the African Diaspora a sense of its strength and… unity,” Goldman told NPR on the album’s 30th anniversary, while at the same time, “really embracing, you know, white people, to an extent; doing his best to make a multicultural world work.” Related Content: Watch a Young Bob Marley and The Wailers Perform Live in England (1973): For His 70th Birthday Today 30 Fans Joyously Sing the Entirety of Bob Marley’s Legend Album in Unison Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How Bob Marley Came to Make Exodus, His Transcendent Album, After Surviving an Assassination Attempt in 1976 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

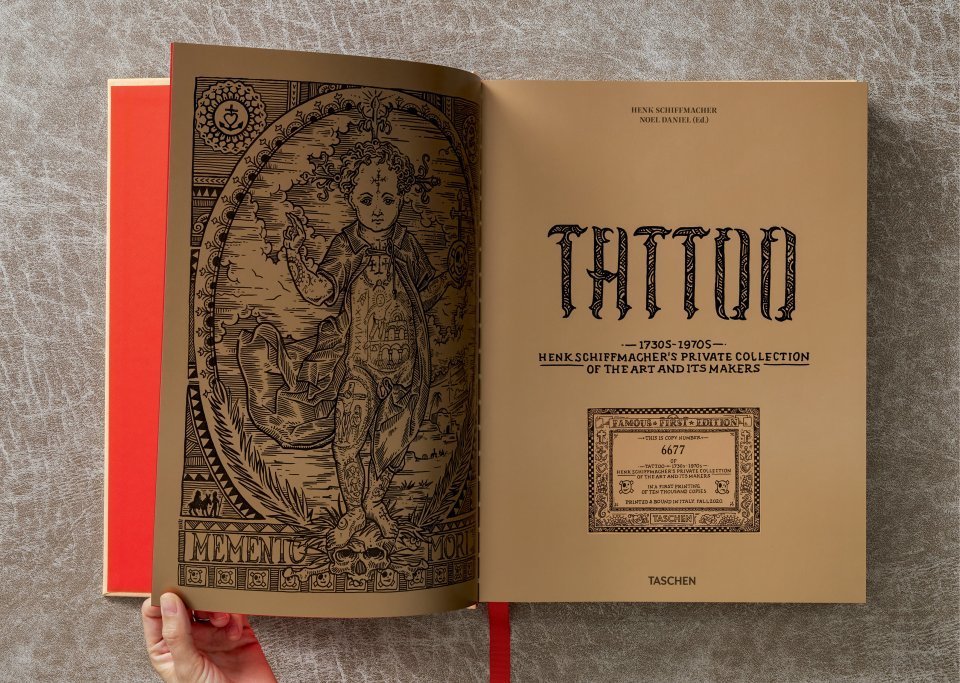

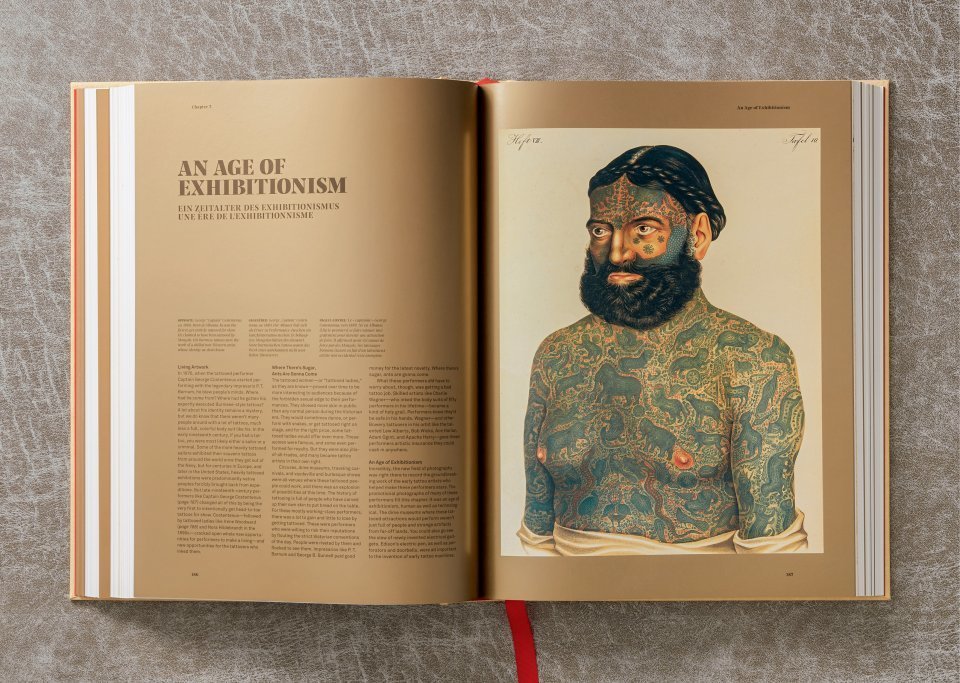

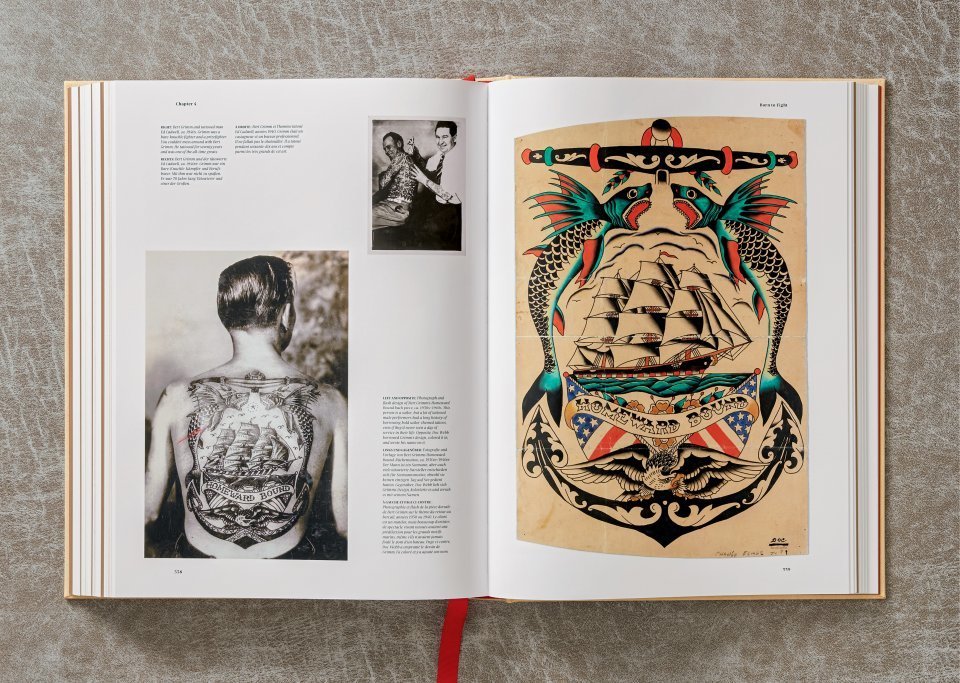

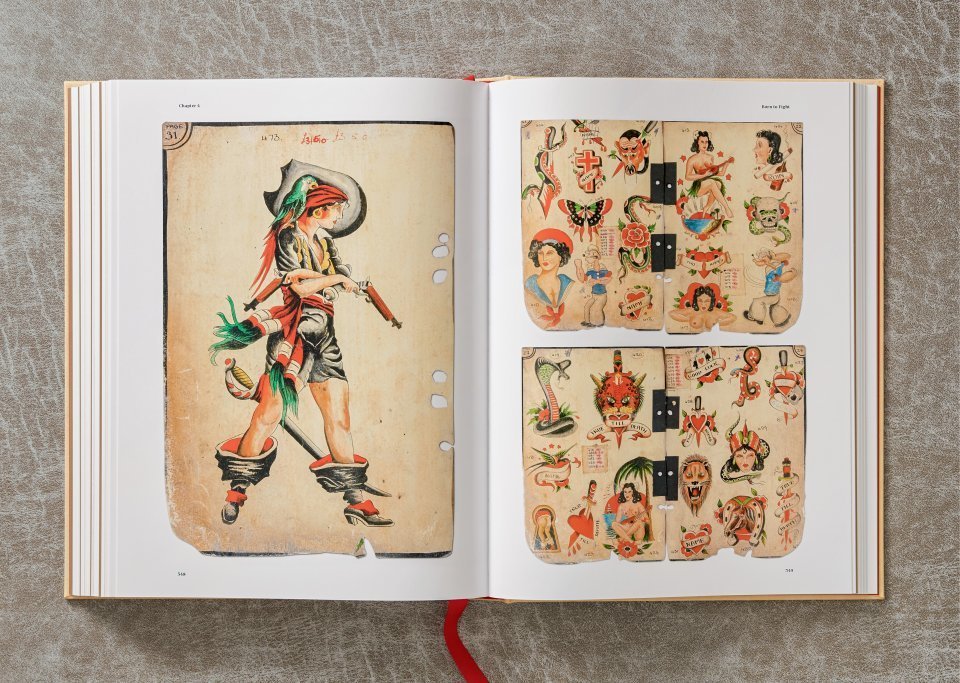

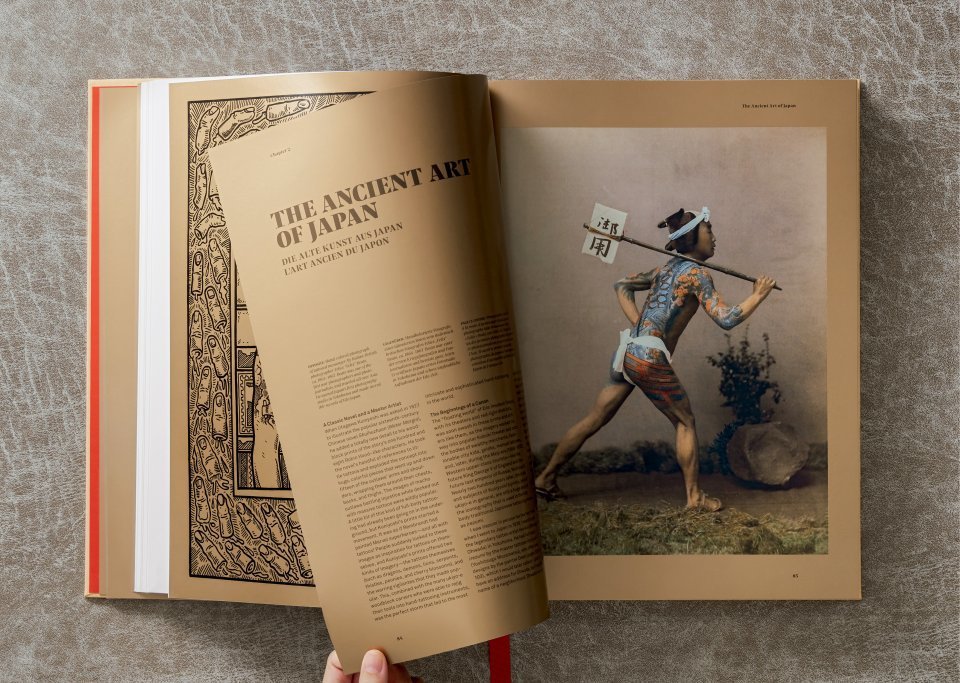

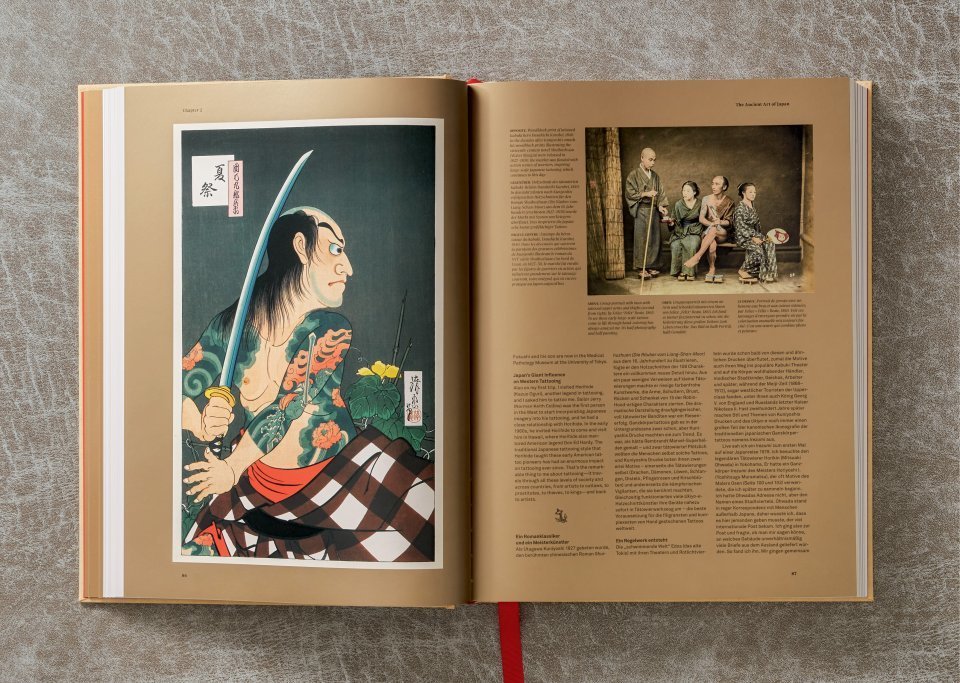

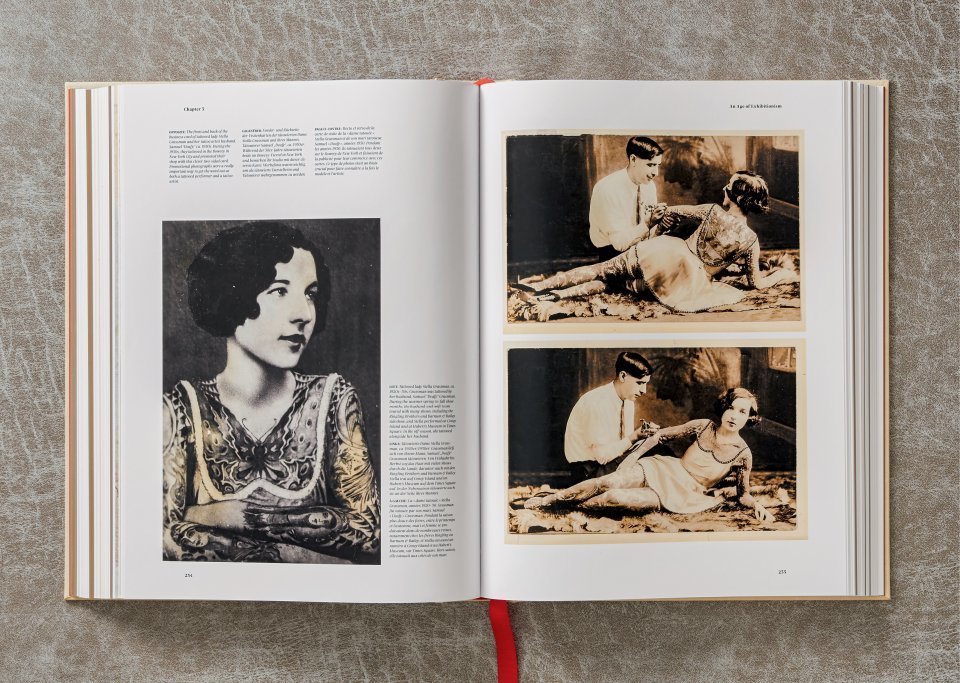

| 2:00p | The History of Tattoos Gets Beautifully Documented in a New Book by Legendary Tattoo Artist Henk Schiffmacher (1730-1970)

Tattooing is an ancient art whose grip on the American mainstream, and that of other Western cultures, is a comparatively recent development. Long before he took up—or went under—a tattoo needle, legendary tattoo artist and self-described “very odd duck type of guy,” Henk Schiffmacher was a fledgling photographer and accidental collector of tattoo lore. Inspired by the immersive approaches of Diane Arbus and journalist Hunter S. Thompson, Schiffmacher, aka Hanky Panky, attended tattoo conventions, seeking out any subculture where inked skin might reveal itself in the early 70s.

As he shared with fellow tattooer Eric Perfect in a characteristically rollicking, profane interview, his instincts became honed to the point where he “could smell” a tattoo concealed beneath clothing:

When tattoo artists would write to him, requesting prints of his photos, he would save the letters, telling Hero’s Eric Goodfellow:

Such correspondence formed the earliest holdings in what is now one of the world’s biggest collections of contemporary and historical tattoo ephemera.

Schiffmacher realized that tattoos must be documented and preserved by someone with an open mind and vested interest, before they accompanied their recipients to the grave. Many families were ashamed of their loved ones’ interest in skin art, and apt to destroy any evidence of it. On the other end of the spectrum is a portion of a 19th-century whaler’s arm, permanently emblazoned with Jesus and sweetheart, preserved in formaldehyde-filled jar. Schiffmacher acquired that, too, along with vintage tools, business cards, pages and pages of flash art, and some truly hair raising DIY ink recipes for those jailhouse stick and pokes. (He discusses the whaler’s tattoos in a 2014 TED Talk, below). His collection also expanded to his own skin, his first canvas as a tattoo artist and proof of his dedication to a community that sees its share of tourists.

Schiffmacher’s command of global tattoo significance and history informs his preference for communicative tattoos, as opposed to obscure ice breakers requiring explanation. When he first started conceiving of himself as an illustrated man, he imagined the delight any potential grandchildren would take in this graphic representation of his life’s adventures—“like Pippi Longstocking’s father.”

While his Tattoo Museum in Amsterdam is no more, his collection is far from mothballed. Earlier this year, Taschen published TATTOO. 1730s-1970s. Henk Schiffmacher’s Private Collection, a whopping 440-pager the irrepressible 69-year-old artist hefts with pride. You can purchase the book directly from Taschen, or via Amazon. Related Content: Why Tattoos Are Permanent? New TED Ed Video Explains with Animation Browse a Gallery of Kurt Vonnegut Tattoos, and See Why He’s the Big Gorilla of Literary Tattoos Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker, the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and the human alter ego of L’Ourse. Follow her @AyunHalliday. The History of Tattoos Gets Beautifully Documented in a New Book by Legendary Tattoo Artist Henk Schiffmacher (1730-1970) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 7:05p | Watch the Classic Silent Film The Ten Commandments (1923) with a New Score by Steve Berlin (Los Lobos), Steven Drozd (Flaming Lips) & Scott Amendola For Passover 2021, the culture nonprofit Reboot has released “a modern day score to Cecil B. Demille’s 1923 classic silent film The Ten Commandments with Steve Berlin (Los Lobos), Steven Drozd (Flaming Lips) and Scott Amendola.” Reboot writes: “Berlin, Drozd and Amendola created a momentous new score for the Exodus tale, musically following Moses out of Egypt and into the Dessert where he receives the Ten Commandments. Cecil B. DeMille’s first attempt at telling the Ten Commandments story was in the Silent era year of 1923. The film [now in the public domain] is broken up into two stories: the story of the Jewish Exodus from Egypt and a thinly related ‘present day’ melodrama.” Enjoy it all above. Related Content: Watch the German Expressionist Film, The Golem, with a Soundtrack by The Pixies’ Black Francis Radiohead’s Thom Yorke Performs Songs from His New Soundtrack for the Horror Film, Suspiria Watch the Classic Silent Film The Ten Commandments (1923) with a New Score by Steve Berlin (Los Lobos), Steven Drozd (Flaming Lips) & Scott Amendola is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 9:00p | Hear J.S. Bach’s Music Performed on the Lautenwerck, Bach’s Favorite Lost Baroque Instrument If you want to hear the music of Johann Sebastian Bach played on the instruments that actually existed during the stretch of the 17th and 18th centuries in which he lived, there are ensembles specializing in just that. But a full musical revival isn’t quite as simple as that: while there are baroque cellos, oboes, and violas around, not every instrument that Bach knew, played, and composed for has survived. Take the lautenwerck, a category of “gut-stringed instruments that resemble the harpsichord and imitate the delicate soft timbre of the lute,” according to Baroquemusic.org. Of the “lute-harpsichord” craftsmen in 18th-century Germany remembered by history, one name stands out: Johann Nicolaus Bach. A second cousin of Johann Sebastian, he “built several types of lute-harpsichord. The basic type closely resembled a small wing-shaped, one-manual harpsichord of the usual kind. It only had a single (gut-stringed) stop, but this sounded a pair of strings tuned an octave apart in the lower third of the compass and in unison in the middle third, to approximate as far as possible the impression given by a lute. The instrument had no metal strings at all.” This gave the lautenwerck a distinctive sound, quite unlike the harpsichord as we know it today. You can hear it — or rather, a reconstructed example — played in the video above, a short performance of Bach’s Prelude, Fugue, and Allegro in E-flat, BWV 998 by early-music specialist Dongsok Shin. “If he owned two of them, they couldn’t have been that off the wall,” Shin says of the composer and his relationship to this now little-known instrument in a recent NPR segment. “The gut has a different kind of ring. It’s not as bright. The lautenwerck can pull certain heartstrings.” Just as the sound of each lautenwerck must have had its own distinctive characteristics in Bach’s day, so does each attempt to recreate it today. “The small handful of artisans currently making lautenwerks are basically forensic musicologists,” notes NPR correspondent Neda Ulaby, “reconstructing instruments based on research and what they think lautenwercks probably sounded like.” As for the one man we can be sure knew them intimately enough to tell the difference, he’d be turning 336 years old right about now. via NPR Related Content: Hear 10 of Bach’s Pieces Played on Original Baroque Instruments Watch J.S. Bach’s “Air on the G String” Played on the Actual Instruments from His Time Musicians Play Bach on the Octobass, the Gargantuan String Instrument Invented in 1850 What Guitars Were Like 400 Years Ago: An Introduction to the 9 String Baroque Guitar Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Hear J.S. Bach’s Music Performed on the Lautenwerck, Bach’s Favorite Lost Baroque Instrument is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/03/30 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |