[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Friday, April 9th, 2021

- Some history from Wikipedia

- “How Independent European Animation Is Taking on the US Studios” by Geoffrey Macnab

- “The 20 Best Indie Animation Features of the 2010s” by Vassilis Kroustallis

- “Oscars Predictions: Best Animated Short – Netflix’s Look at the Aftermath of School Shootings is the One to Beat” by Clayton Davis

- “Oscars Predictions: Best Animated Feature – Can Anything Beat ‘Soul’ at the Oscars?” by Clayton Davis

| Time | Event |

| 7:01a | Indie Animation in a Corporate World: A Conversation with Animator Benjamin Goldman on Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #88

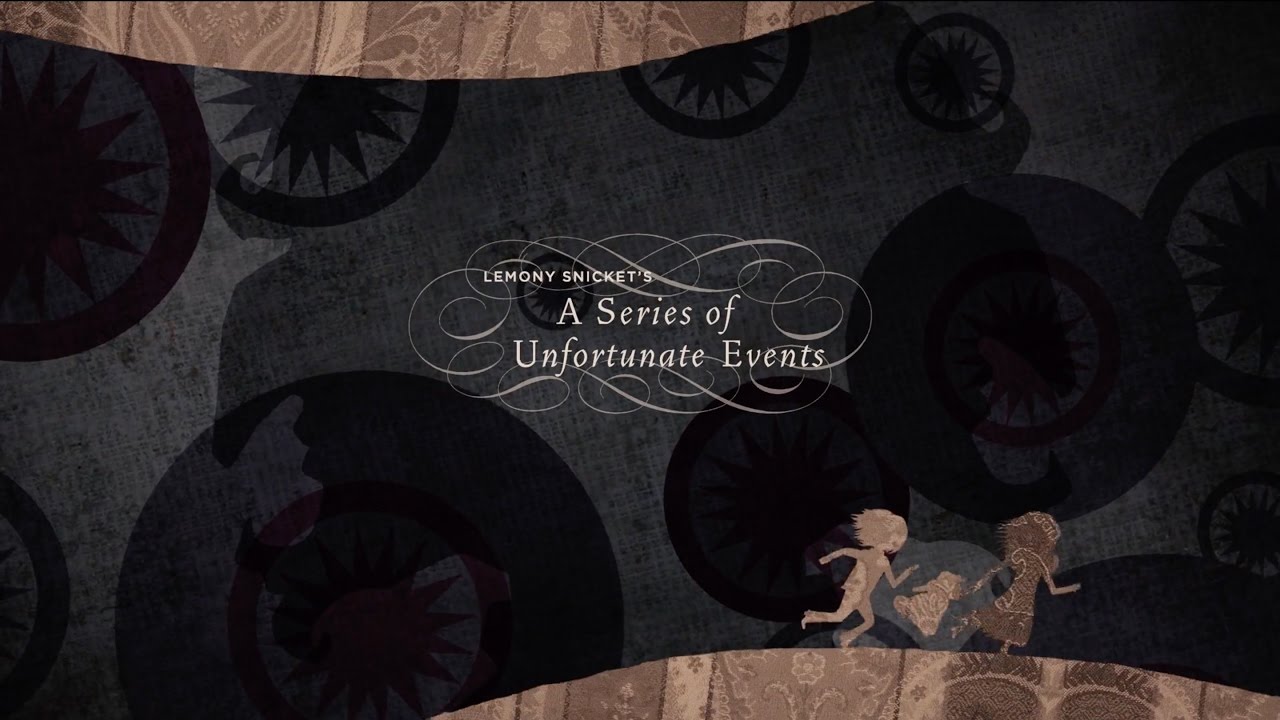

In the perennial conflict between art and our corporate entertainment machine, animation seems designed to be mechanized, given how labor-intensive it is, and yes, most of our animation comes aimed at children (or naughty adults) from a few behemoths (like, say, Disney). Your hosts Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt are joined by Benjamin Goldman to discuss doing animation on your own, with only faint hope of “the cavalry” (e.g. Netfilx money or the Pixar fleet of animators) coming to help you realize (and distribute and generate revenue from) your vision. As an adult viewer, what are we looking for from this medium? We talk about what exactly constitutes “indie,” shorts vs. features, how the image relates to the narration, realism or its avoidance, and more. Watch Benjamin’s film with Daniel Gamburg, “Eight Nights.” Some of our other examples include Jérémy Clapin’s I Lost My Body and Skhizein, World of Tomorrow, If Anything Happens I Love You, The Opposites Game, Windup, Fritz the Cat, Spike & Mike’s Sick and Twisted Festival of Animation, and Image Union. Hear a few lists and comments about this independent animation: Follow Benjamin on Instagram @bgpictures. Here’s something he did for a major film studio that you might recognize, from the film version of A Series of Unfortunate Events: Hear more of this podcast at prettymuchpop.com. This episode includes bonus discussion that you can access by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts. Indie Animation in a Corporate World: A Conversation with Animator Benjamin Goldman on Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #88 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00a | Watch a Master Japanese Printmaker at Work: Two Unintentionally Relaxing ASMR Videos Today we can appreciate Japanese woodblock prints from sizable online archives whenever we like, and even download them for ourselves. Before the internet, how many chances would we have had even to encounter such works of art in the course of life? Very few of us, certainly, would ever have beheld a Japanese printmaker at work, but here in the age of streaming video, we all can. In the Smithsonian video above, printmaker Keiji Shinohara demonstrates a suite of traditional techniques (and more specialized ones in a follow-up below) for creating ukiyo-e, the “pictures of the floating world” whose style originally developed to capture Japanese life and landscapes of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. “So uh,” asks one commenter below this video of Shinohara at work, “anyone else come from unintentional ASMR?” That abbreviation, which stands for “autonomous sensory meridian response,” labels a genre of Youtube video that exploded in popularity in recent years. Attempts have been made to define the underlying phenomenon scientifically, but suffice it to say that ASMR involves a set of distinctively pleasurable sounds that happens to coincide with those made by the tools of printmakers and other highly analog craftsmen. When ASMR enthusiasts discovered Youtube art conservator Julian Baumgartner, previously featured here on Open Culture, he created special sonically enhanced versions of his videos just for them. In the case of Shinohara, the Best Unintentional ASMR channel has done it for him. Its version of his videos greatly emphasize the sounds of brushes rubbed against paper, inks spread onto wood, and droplets of water falling into the rinsing bowl. Of course, the original king of unintentional ASMR in art is universally acknowledged to be Bob Ross, host of The Joy of Painting, whose soft-spoken industriousness seems now to inhabit the person of David Bull, an English-Canadian ukiyo-e printmaker living in Tokyo. In a sense, Bull is the Western counterpart to the Osaka-born Shinohara, who after a decade’s apprenticeship in Kyoto crossed the Pacific Ocean in the other direction to make his home in the United States. But however traditional their art, they both belong, now to the floating world of the internet. You can listen to non-ASMR versions of the videos above here and here. Related Content: Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600-1915) Watch the Making of Japanese Woodblock Prints, from Start to Finish, by a Longtime Tokyo Printmaker Watch a Japanese Craftsman Lovingly Bring a Tattered Old Book Back to Near Mint Condition Watch an Art Conservator Bring Classic Paintings Back to Life in Intriguingly Narrated Videos Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Watch a Master Japanese Printmaker at Work: Two Unintentionally Relaxing ASMR Videos is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | Watch Preciously Rare Footage of Paul McCartney Recording “Blackbird” at Abbey Road Studios (1968) Paul McCartney’s “Blackbird” competes with Lennon’s “Julia” as the most tender song on the Beatles’ White Album and maybe in the band’s entire catalogue. Inspired by a Bach piece that McCartney and George Harrison learned to play when they were young, its finger-picked acoustic guitar has the sound of a folk lullaby. But the song’s shifting time signatures and delicate melody make it something of a tricky one: recording sessions at Abbey Road involved a series of 32 takes, most of them false starts and only 11 complete. The version we hear on the album is the final take, finished while Lennon worked on “Revolution 9” in the studio next door. You can see 1:33 of that session in the footage above, captured on 16mm by a film crew from Apple Records directed by Tony Bramwell, part of a 10-minute promo that also included footage of McCartney recording “Helter Skelter” and “various other scenes from inside the studio, in the Apple Boutique, Apple Tailoring, McCartney’s garden and other locations,” the Beatles Bible notes. It’s an ephemeral document of time passing peaceably during the grueling 5-month White Album sessions, which for all their legendary tension and rancor, included many moments like these. The three-day ordeal that was the recording of “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” (after which engineer Geoff Emerick quit) provides stark contrast, and maybe confirmation that the Beatles were at their best when they worked separately in 1968. The brief film above also confirms a more technical recording concern: the ticking we hear in the studio track is not a metronome, but Paul’s feet alternately tapping on the wood studio floor to measure out the bars of the complex song, which shifts between 3/4, 4/4, and 2/4 time. “Part of its structure is a particular harmonic thing between the melody and the bass line which intrigued me,” he remembered, and we see him striving to get it right. After the Beatles, McCartney made “Blackbird” a regular part of his set, playing it at nearly every concert from 1975 on. It wasn’t only the beauty of the song that has moved him all these years, but its inspiration, the Civil Rights movement, which “all of us cared passionately about,” he said. “Blackbird” is “symbolic, so you could apply it to your particular problem,” but the song’s intended message, he said, was “from me to a black woman, experiencing these problems in the States: ‘Let me encourage you to keep trying, to keep your faith, there is hope.’” Below you can watch McCartney talk about the story behind “Blackbird” in a 2005 production called Chaos & Creation at Abbey Road. via Boing Boing Related Content: When the Beatles Refused to Play Before Segregated Audiences on Their First U.S. Tour (1964) How “Strawberry Fields Forever” Contains “the Craziest Edit” in Beatles History Hear the Beautiful Isolated Vocal Harmonies from the Beatles’ “Something” Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Watch Preciously Rare Footage of Paul McCartney Recording “Blackbird” at Abbey Road Studios (1968) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

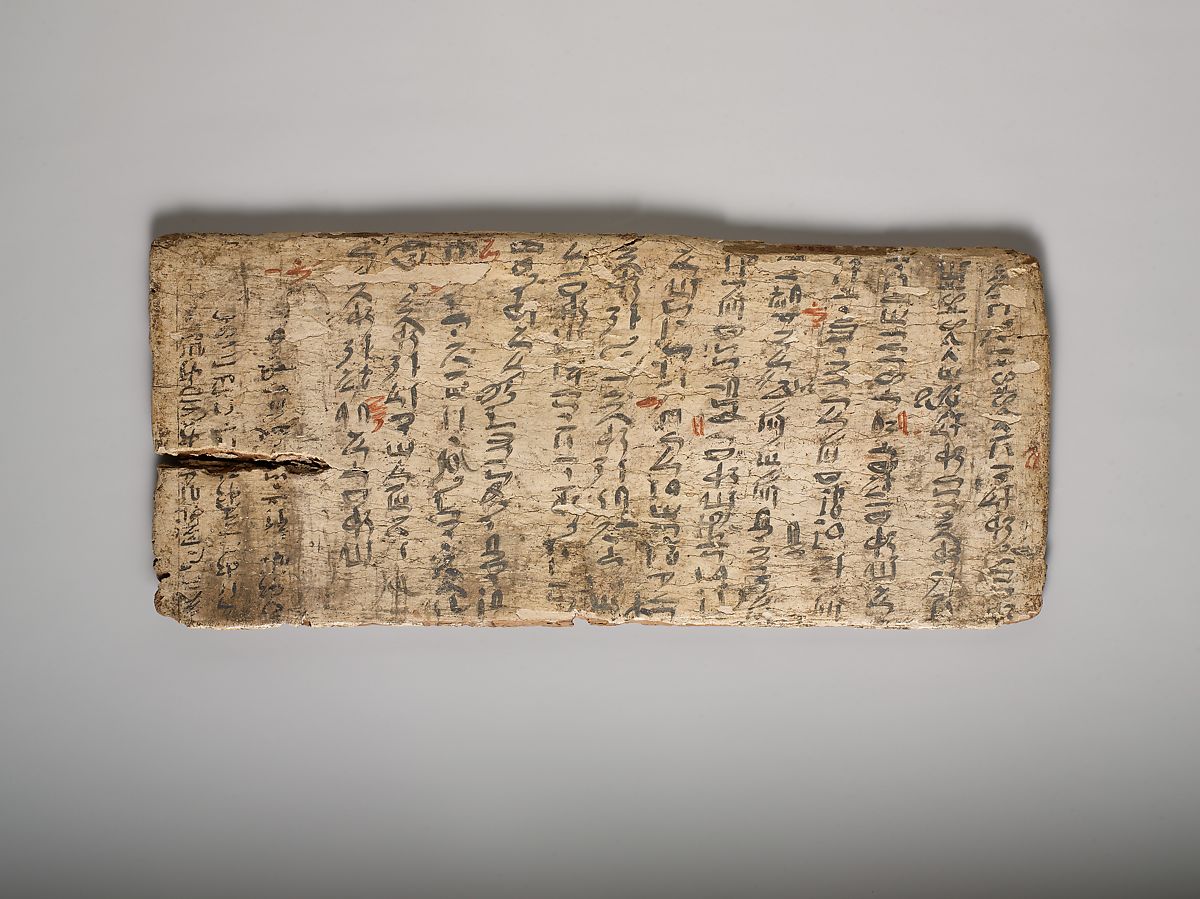

| 2:00p | A 4,000-Year-Old Student ‘Writing Board’ from Ancient Egypt (with Teacher’s Corrections in Red)

Had we been reared along the banks of the Nile, would our minds go to ancient gessoed boards like the 4000-year-old Middle Kingdom example above? Like our familiar tablet-sized blackboards, this paper — or should we say papyrus? — saver was designed to be used again and again, with whitewash serving as a form of eraser. As Egyptologist William C. Hayes, former Curator of Egyptian Art at the Metropolitan Museum wrote in The Scepter of Egypt: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom, the writing board at the top of the page:

Iny-su would also have been expected to memorize the text he had copied out, a practice that carried forward to our one-room-schoolhouses, where children droned their way through texts from McGuffey’s Eclectic Readers.

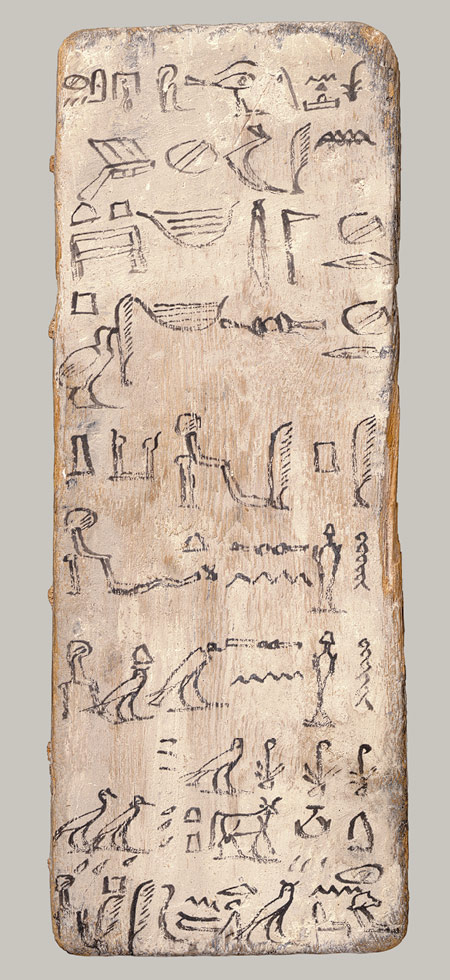

Another ancient Egyptian writing board in the Met’s collection finds an apprentice scribe fumbling with imperfectly formed, unevenly spaced hieroglyphs. Fetch the whitewash and say it with me, class — practice makes perfect. The first tablet inspired some lively discussion and more than a few punchlines on Reddit, where commenter The-Lord-Moccasin mused:

We can’t verify it, but we second that emotion. Note: The red markings on the image up top indicate where spelling mistakes were corrected by a teacher. via @ddoniolvalcroze Related Content: What Ancient Egyptian Sounded Like & How We Know It Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday. A 4,000-Year-Old Student ‘Writing Board’ from Ancient Egypt (with Teacher’s Corrections in Red) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/04/09 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |