[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, April 29th, 2021

| Time | Event |

| 7:02a | Has TV Rotted Our Minds? On Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death (A Pretty Much Pop Culture Podcast/Partially Examined Life Philosophy Podcast Crossover)

Marshall McLuhan famously said “The medium is the message,” by which he meant that when we receive information, its effect on us is determined as much by the form of that information as by the actual content. Neil Postman, in his 1985 book Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, ran with this idea, arguing that TV has conditioned us to expect that everything must be entertaining, and that this has had a disastrous effect on news, politics, education, and thinking in general. In this discussion, your Pretty Much Pop hosts Mark Linsenmayer and Brian Hirt join with the rest of the Partially Examined Life crew: Seth Paskin, Dylan Casey and Wes Alwan. The result is much more philosophical context than you’d get in a typical Pretty Much Pop discussion. Plato, for example, argued (through the character of Socrates) in the Phaedrus against writing, which he said amounts to off-loading thought to this inert thing, when it should be lively in our minds and our direct conversations. Postman’s book describes the Age of Print as highly congenial toward lengthy, abstract reasoning. High literacy rates, particularly in America, conditioned people to expect that this is how information is to be received, and as such they were, for instance, prepared to listen raptly to the Lincoln-Douglas debates in which the speakers provided lawyerly speeches that might span multiple hours. Postman, an educational theorist, described television as not just providing a no-context experience whose high level of visual and auditory stimulation beats its spectators into thoughtless passivity, but that its popularity positively infects all the other communication channels available. Of course there is still in-person teaching, but television shortens attention spans such that teachers now feel the need to constantly entertain instead of forcing students to make the effort required to attend carefully to what they have to teach. Of course there are still books, but they are less read, and the competition of television for our time has changed the presentation within books so that they must be as immediately and consistently appealing as television. McLuhan described television as a “hot” medium due to its high level of stimulation, where a “cool” one like a textbook requires more active participation of the recipient. We discuss how Postman’s critique fares in the Age of the Internet, which interestingly mixes things up, with more interactivity (in that sense cooler) yet even more possibility for sensory distraction (in that perhaps more important sense hotter). To supplement Postman, we also consulted a widely read article from The Atlantic written by Nicholas Carr in 2008 called “Is Google Making Us Stupid.” For more philosophical touchpoints, see the post for this discussion at partiallyexaminedlife.com. Hear more Pretty Much Pop at prettymuchpop.com. This episode includes an equally long second part that you can access by supporting Pretty Much Pop at patreon.com/prettymuchpop or by supporting The Partially Examined Life at partiallyexaminedlife.com/support. Listen to a preview of part two. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts. Has TV Rotted Our Minds? On Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death (A Pretty Much Pop Culture Podcast/Partially Examined Life Philosophy Podcast Crossover) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00a | How the Clash Embraced New York’s Hip Hop Scene with Their Single “The Magnificent Seven” & “The Magnificent Dance” “Before playing guitar for Captain Beefheart and Jeff Buckley,” John Kruth writes at the Observer, “Gary Lucas worked as a copywriter for CBS/Epic Records,” where he fell in love with a punk band called the Clash, just signed to the label in 1977. “They weren’t easy to work with,” he remembered. “Like Frank Zappa, they spoke about politics, government and corporate interference with radio. They were, as I said, when I came up with the slogan to promote the album: ‘The only group that matters.’” The slogan stuck and has become something more than marketing hype. Of the slew of British punk bands who made their way to the US in the late 1970s/early 1980s, the Clash had more impact than most others in some unexpected ways. Their classic double album London Calling made Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine (the only 90s rap-rock band that matters) take notice and change direction. “It was music I could relate to lyrically,” he says, “much more than the dungeons-and-dragons type lyrics of my metal forebears.” Moreover, godfathers of political rap Public Enemy found their catalyst in the Clash, and went on to create a raucous, militant sound that was the punk equivalent in hip hop, full of snarling guitars, strident declarations and sirens. The song that most had an impact on PE founder and chief lyricist Chuck D came from the band’s even more sprawling triple album Sandinista!. When Chuck heard “The Magnificent Seven,” the Clash’s attempt to incorporate Grandmaster Flash and the Sugar Hill Gang — six months before Blondie released “Rapture” — “that’s when I started to pay attention,” he says. “Magnificent Seven” came out of the band’s increasing musical adventurousness in the recording of 1980’s Sandinista!, in which they soaked up influences from every place they toured. “When we visited places,” Mick Jones remembered, “we were affected by that… And for me, New York City was really happening at that moment.” Jones took to carrying a boom box around blasting the latest hip hop. “Joe looked at the graffiti artists,” he says, “and I was taking in things like breakdancing and rap.” The band, bassist Paul Simenon recalls, was “open for information” when they met “people like Futura and Grandmaster Flash and Kurtis Blow.” The Clash didn’t only take from hip hop, but they tried to give back as well. Their 1981 run at “an aging Times Square Disco,” Jeff Chang writes, proved to be a major opportunity for graffiti artists like Futura, who painted a huge banner that was unfurled onstage every night and got to deliver his own rap while the band backed him. When the Clash announced an additional 11 shows after the NYPD limited capacity, they showed what Chang calls a “naive act of solidarity,” booking Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five as an opening act. White American punks sneered at the group; the Clash “responded by excoriating their own fans in interviews, and future Bronx-bred openers, The Treacherous Three and ESG, received marginally better treatment.” Even more exciting was the fact that the B-side to “The Magnificent Seven,” a dub remix called “The Magnificent Dance,” had made it to New York hip hop radio and made the band unlikely stars among black American listeners. “The Clash were ecstatic to tune into WBLS and find that the DJs were not only playing ‘The Magnificent Dance’ up to five times a day, but also doing their own remixes of it,” writes Marcus Gray, “dubbing on samples from the soundtrack of Dirty Harry.” While the track, with its loping bass line played by Ian Drury and the Blockheads bassist Norman Watt-Roy, primed dance floors for the success of the following year’s funk/disco “Rock the Casbah,” it was the lyrics that most grabbed listeners like Morello and Chuck D. “They talked about important subjects,” says Chuck, “so therefore journalists printed what they said…. We took that from the Clash, because we were very similar in that regard. Public Enemy just did it 10 years later.” It may have been that long for the barriers between punk and hip hop fans to come down, but to the extent that they did, it was thanks to the musical adventurousness of the Clash and the early hip hop fans and DJs who saw their revolutionary potential. Related Content: “Stay Free: The Story of the Clash” Narrated by Public Enemy’s Chuck D: A New 8-Episode Podcast The Story Behind the Iconic Bass-Smashing Photo on the Clash’s London Calling Watch Audio Ammunition: A Documentary Series on The Clash and Their Five Classic Albums Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How the Clash Embraced New York’s Hip Hop Scene with Their Single “The Magnificent Seven” & “The Magnificent Dance” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

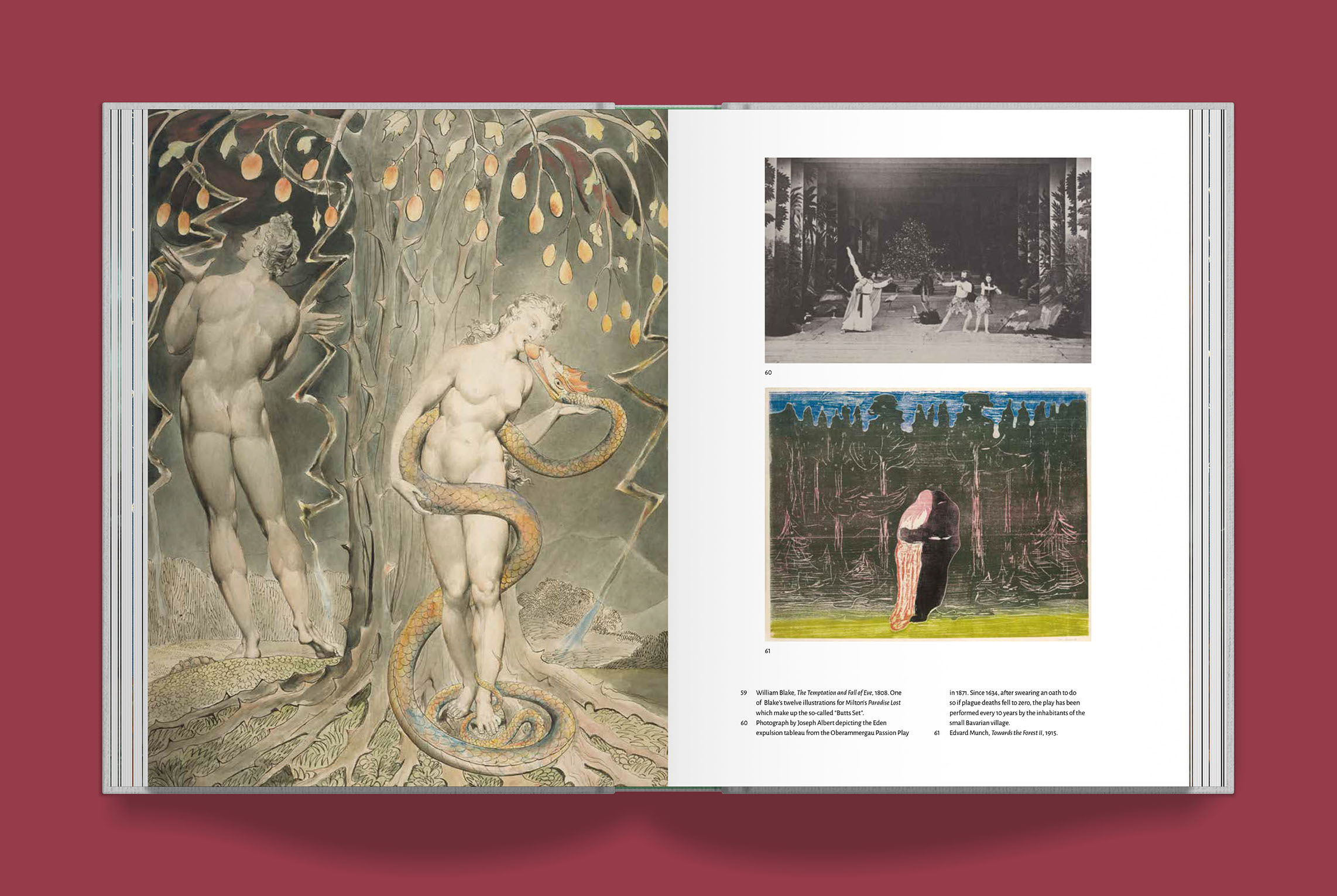

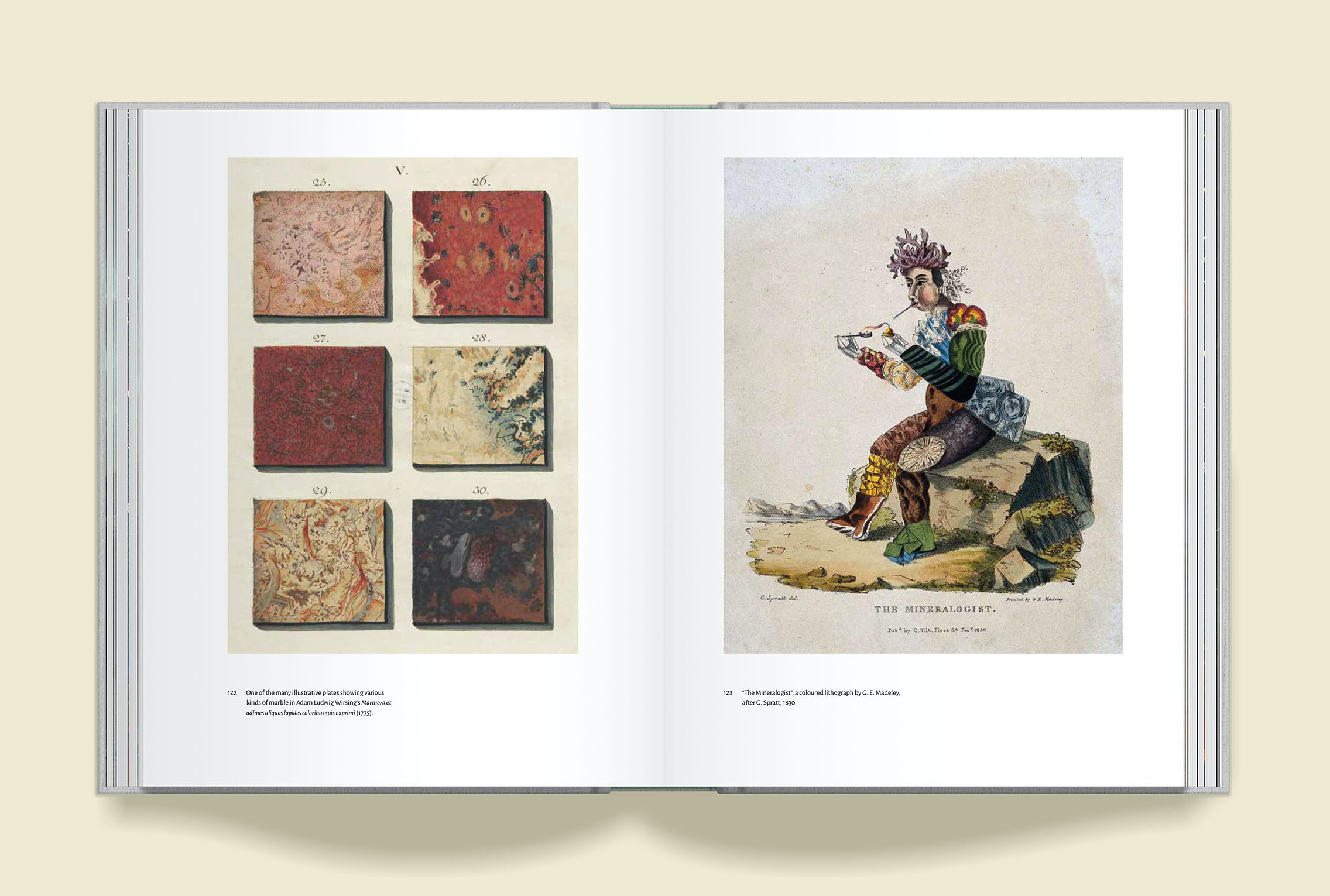

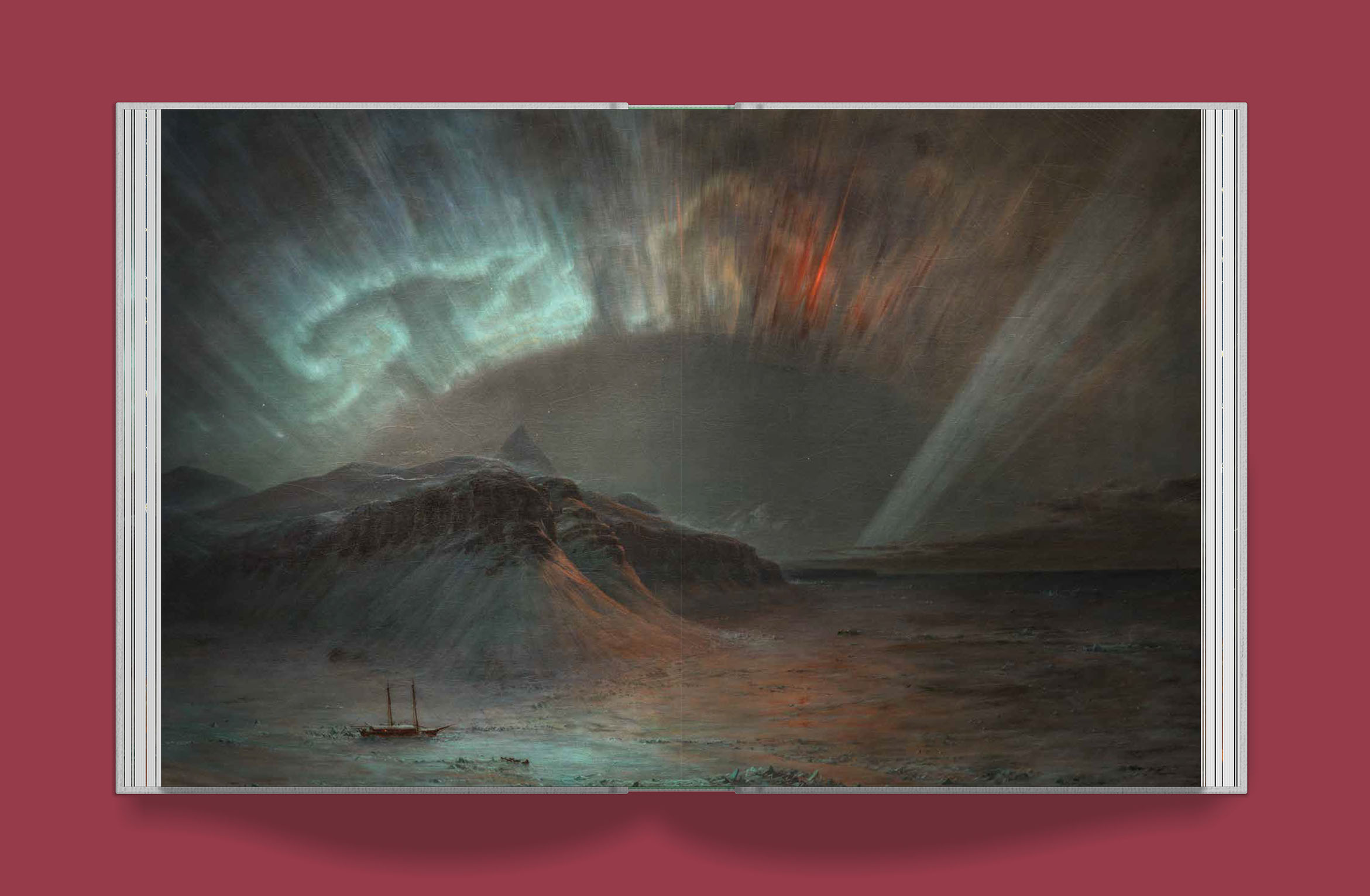

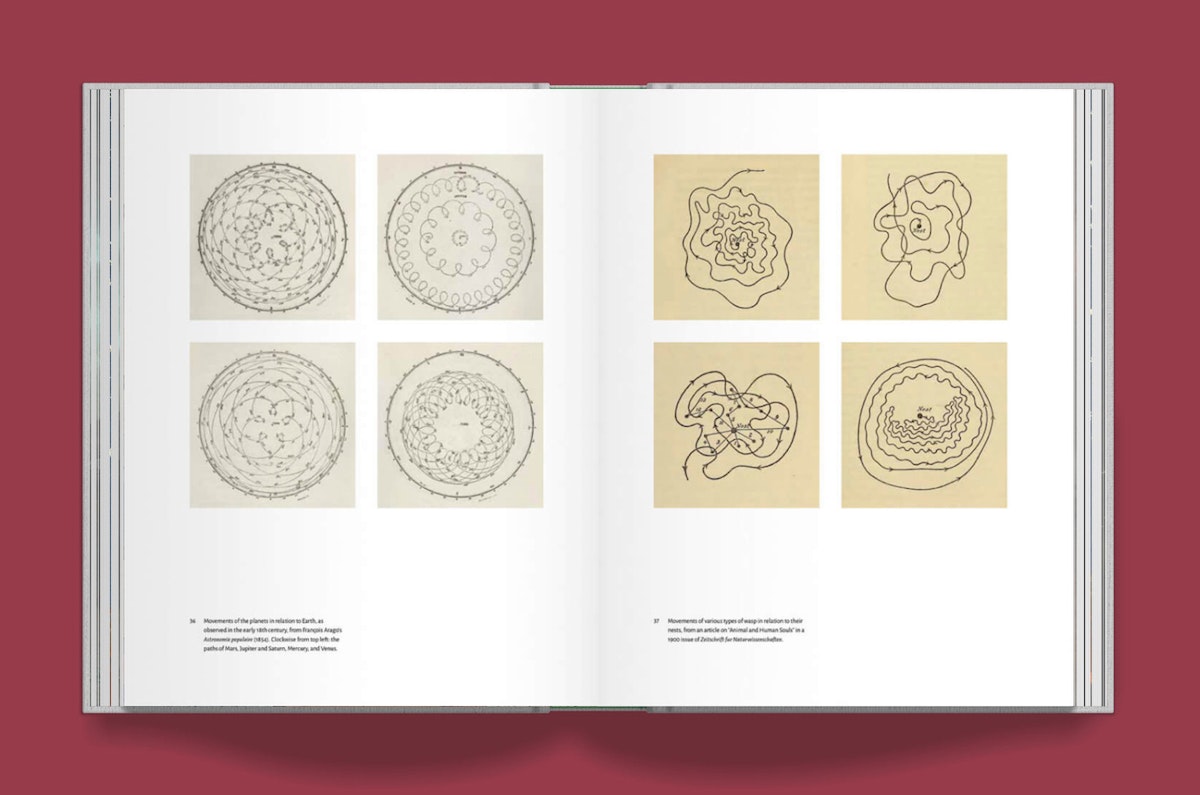

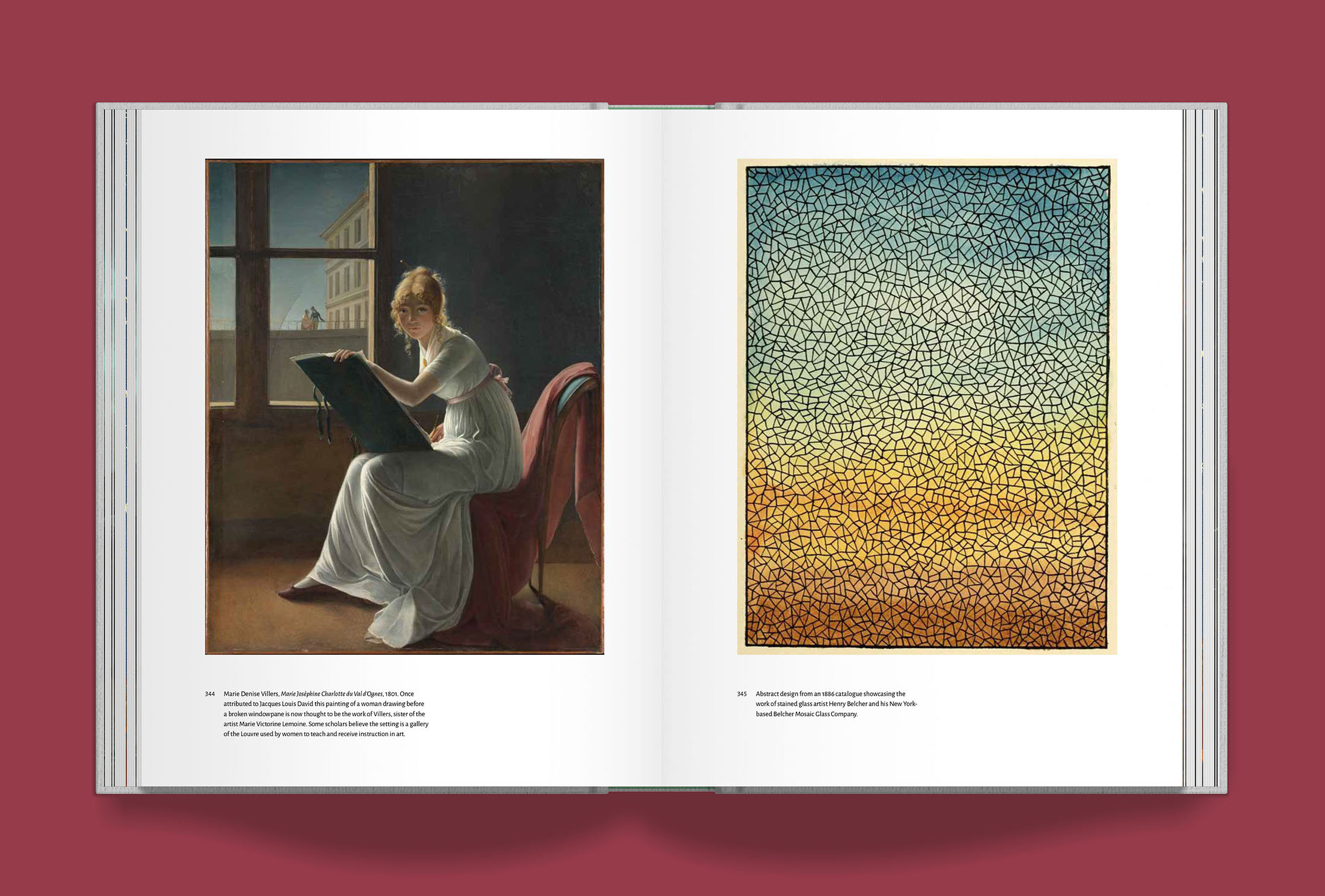

| 2:00p | Affinities, a Book of Images to Celebrate 10 Years of The Public Domain Review

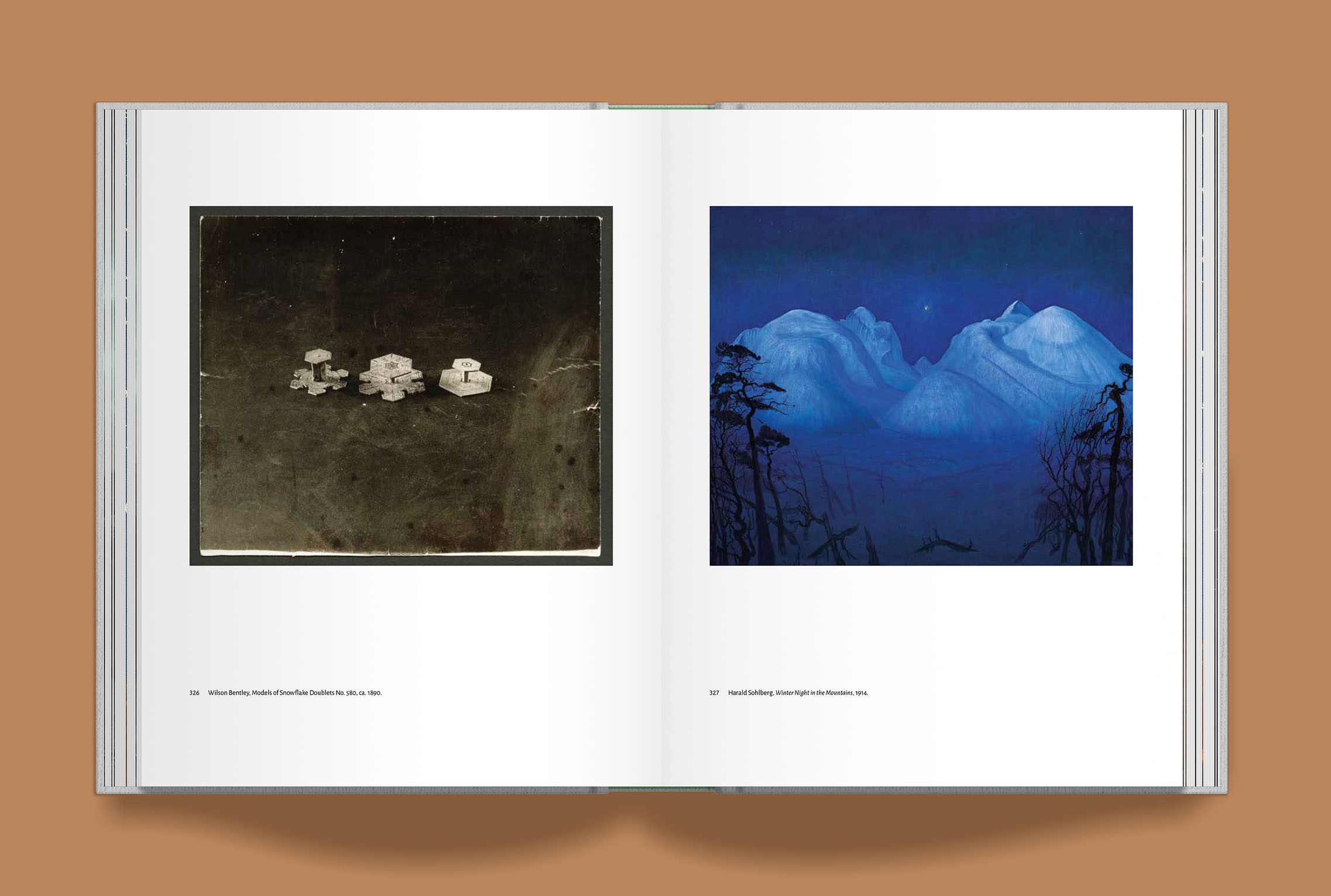

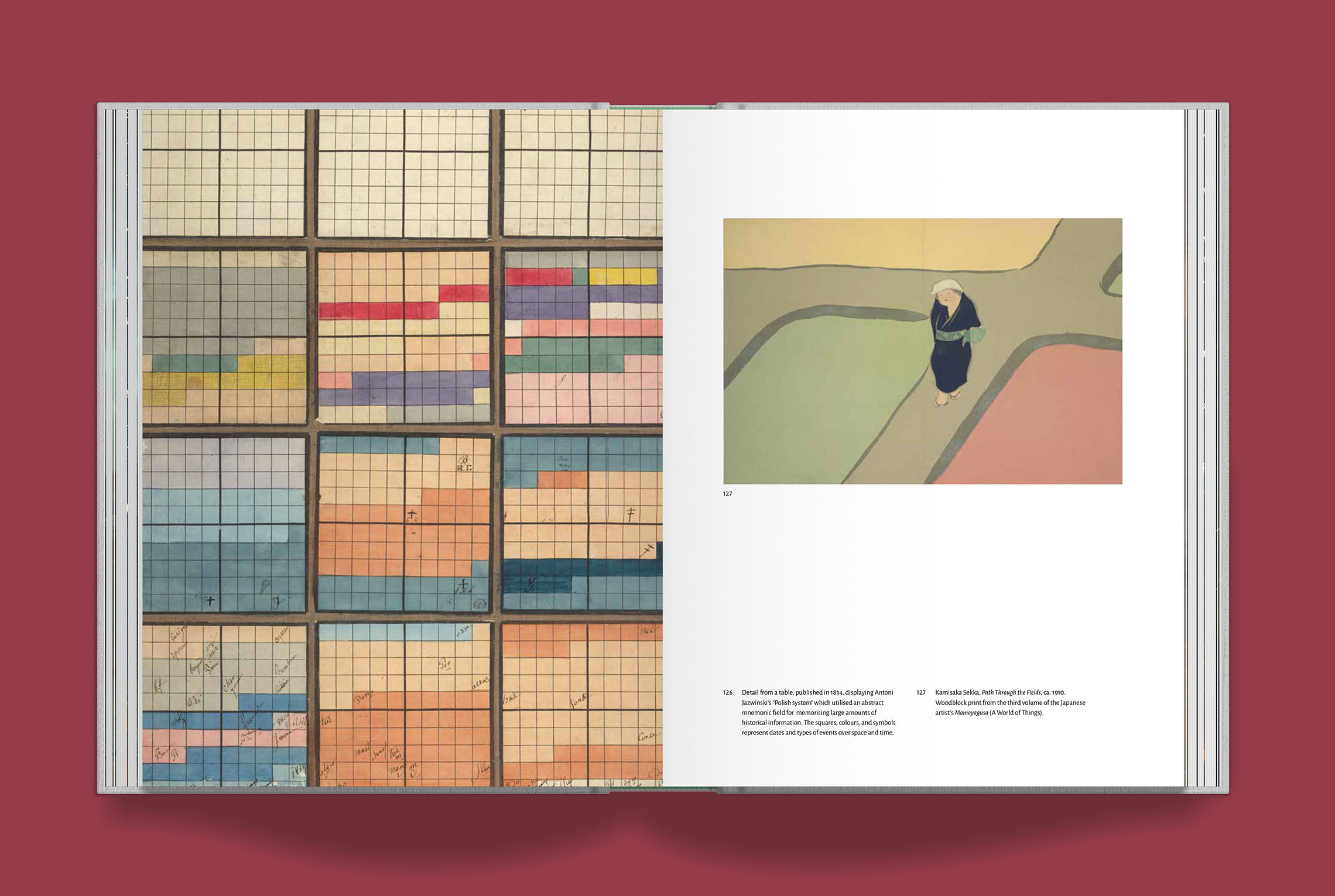

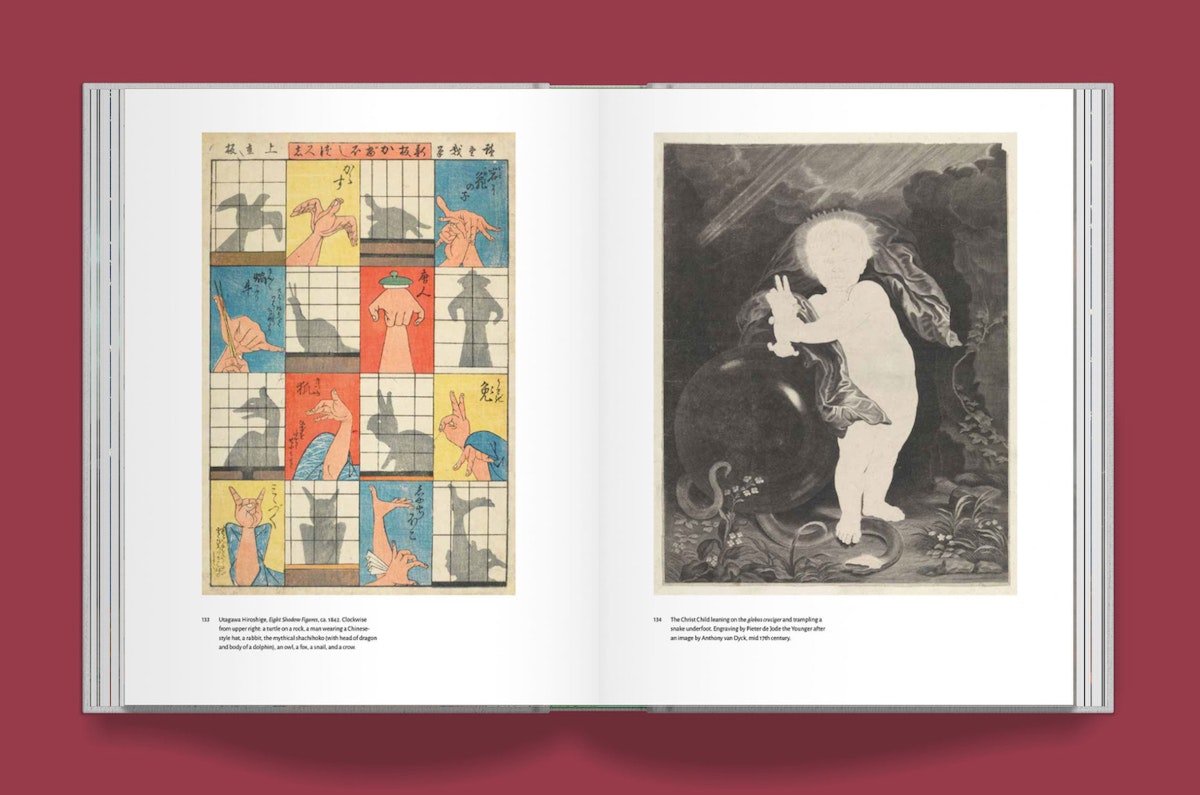

In a similar way to how Open Culture aims to distill in one place the web’s high-quality free cultural and educational media, so The Public Domain Review aims to help readers explore the vast (and sometimes overwhelming!) sea of public domain works available online — like a small exhibition gallery at the entrance to an immense network of archives and storage rooms that lie beyond. Celebrating curious and beautiful public domain images is at the very heart of what we do, and so it seemed fitting to mark our 10th anniversary with a big and beautiful book of images. Ever since the project began back in 2011, readers have implored us to do one, and so finally here it is… we are extremely excited to bring out into the world AFFINITIES. Gathering over 500 prints, paintings, illustrations, sketches, photographs, doodles, and everything in between, the book is a carefully curated journey exploring echoes and connections across more than two millennia of visual culture. Assembled according to a dreamlike logic, the images unfurl in a single unbroken sequence, through a play of visual echoes and evolving thematic threads.

While it’s taken the best part of a year to create (a true lockdown baby), this has really been 10 years in the making — a book born from a decade of deep immersion in public domain archives. A compelling object and experience in its own right, Affinities also acts as a launchpad for further discoveries and inventive engagements with the commons. It’s meticulous sourcing points to works, creators, and collections around the world, serving as a gateway for future forays into the digital public domain. As for the physical book itself, we wanted to create an object as stunning as the images within. It is large format (28 x 21.5cm / 11 x 8.5”), boasts a cloth-bound hardcover, with a foil stamped title and embossed inset image, and extends across a whopping 368 pages. To help get this beauty made and assure the highest quality production, we are very happy to have teamed up with specialist art book publisher Volume, an imprint of Thames & Hudson. It’s being sold via a crowdfunder and delivery will be early next year. In addition to the standard edition of the book, we’ve worked with Volume to create a special Collector’s Edition (in a slipcase with limited edition poster) and also a set of limited edition prints. All of the offerings are only available during the campaign. Learn more, and order your copy, over on the crowdfunder page.

Adam Green is co-founder, creator, and main editor of The Public Domain Review and PDR Press. Affinities, a Book of Images to Celebrate 10 Years of The Public Domain Review is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 5:00p | What Makes Citizen Kane a Great Film: 4 Video Essays Revisit Orson Welles’ Masterpiece on the 80th Anniversary of Its Premiere To understand why Citizen Kane has for so long been referred to as the “greatest film of all time,” simply watch any film made before it. Glib though that often-made prescription may sound, it gets at a truth about Orson Welles’ tale of the rise and fall of an American media magnate, his first and by far his most highly regarded picture, now just days from the eightieth anniversary of its premiere. “Its impact on cinema was so profound, and its techniques became so ubiquitous, that its once-radical ideas now seem commonplace,” says the narrator of the Youtube series One Hundred Years of Cinema, whose episode on the year 1941 could hardly have focused on any other movie. Among Citizen Kane‘s most visible innovations is cinematographer Gregg Toland’s use of deep focus, which allows Welles and his collaborators to make constant narrative use of every visual detail. This encourages the audience to “read the whole frame at once, much in the same way that one would read a painting, each layer adding an element to the story.” More subtly, “what separated Citizen Kane from the kind of films that preceded it was the overall ambivalence of its tone. It’s a film about one of the wealthiest, most successful men in the world, and yet permeating the entire film is the gloom of failure.” The legacy of these and other daring artistic choices manifest in the work of subsequent generations of directors, including such names cited in the brief Fandor video essay above as Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese, Wes Anderson, and Steven Spielberg. “The creators of Citizen Kane had the freedom to play and innovate,” says Michael Aranda in the episode of Crash Course Film Criticism above. “Many of their technical experiments changed the way film was being used as a storytelling medium — which, arguably, could be another way to define ‘greatness.'” Welles himself put it differently: “There is a great gift that ignorance has to bring to anything. That was the gift I brought to Kane, ignorance.” Of course, he had the good excuse of being 25 years old, although already more than established on the stage and the radio. When Hollywood came calling, he brought his creatively spirited Mercury Theatre Players within to make use of the relatively vast production resources available at RKO Pictures. One of Welles’ collaborators in particular has recently been back in the public eye: Herman J. Mankiewicz, who’d previously written scripts for Welles’ Campbell Playhouse series on CBS Radio. David Fincher’s biographical drama Mank, which won a couple of Academy Awards last weekend, tells the story of the troubled screenwriter’s involvement with Citizen Kane. Originally written by Fincher’s father, Mank drew its first inspiration from “Raising Kane,” a 1971 essay by New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael that famously depicted Mankiewicz, not Welles, as Citizen Kane‘s primary author. Subsequent scholarship, as explained in the Royal Ocean Film Society video above, has revealed that Kael was laboring under a misapprehension (if not a grudge). But the fact remains that all the participants in Citizen Kane did their bit to greatly advance the medium of cinema, and for the young Welles the picture became proof of his artistic maturity: a masterpiece, in the original sense. Related Content: Orson Welles Explains Why Ignorance Was His Major “Gift” to Citizen Kane Jorge Luis Borges Reviews Citizen Kane — and Gets a Response from Orson Welles Jean-Paul Sartre Reviews Orson Welles’ Masterwork (1945): “Citizen Kane Is Not Cinema” How Orson Welles’ F for Fake Teaches Us How to Make the Perfect Video Essay What Makes Vertigo the Best Film of All Time? Four Video Essays (and Martin Scorsese) Explain Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. What Makes Citizen Kane a Great Film: 4 Video Essays Revisit Orson Welles’ Masterpiece on the 80th Anniversary of Its Premiere is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/04/29 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |