[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, May 20th, 2021

| Time | Event |

| 7:01a | Why Collect? A Conversation about Collectibles from Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast (#92)

What drives someone to collect Star Wars figures or Transformers or LEGOs or whatever else? Your Pretty Much Pop hosts Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt are joined by guest Matt Young of the Hello from the Magic Tavern and Improvised Star Trek podcasts to talk about this potentially expensive and life-eating habit. No kidulting required. For a little extra information on this topic, you may want to look at Wikipedia on the Psychology of Collecting, this incomplete list of nostalgic collectible IPs (that’s “intellectual property”), or this weird list of collections that includes erasers, confetti, traffic cones and sugar packets. Most of the literature we found in researching this episode was either about what collections might present a future investment opportunity or other tips for doing this as a financial activity (please don’t try to do this) and surprise that adults buy toys. After the episode, Matt remained on the line for our Aftertalk, which is typically only available for supporters via patreon.com/prettymuchpop, but this this case we’ve unleashed it to the public: Hear more of this podcast at prettymuchpop.com. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts. Why Collect? A Conversation about Collectibles from Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast (#92) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

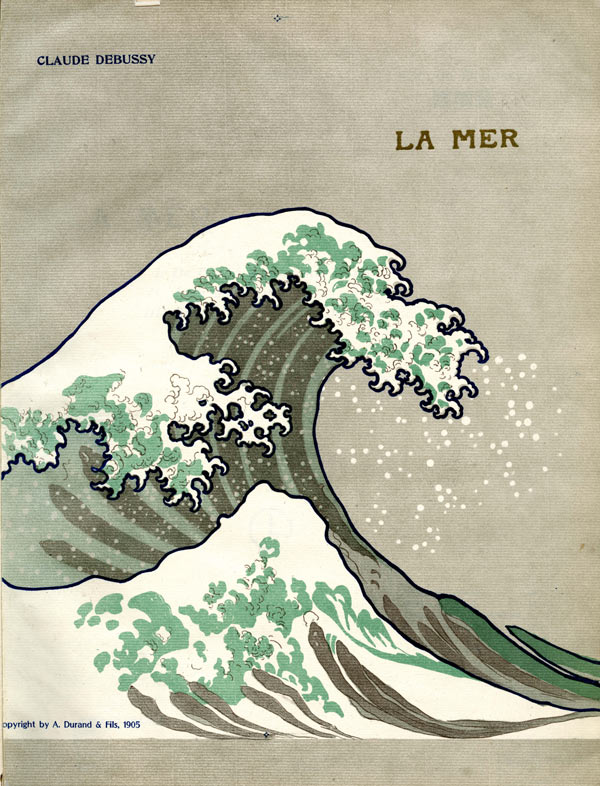

| 8:00a | The Great Wave Off Kanagawa by Hokusai: An Introduction to the Iconic Japanese Woodblock Print in 17 Minutes When woodcut artist Katsushika Hokusai made his famous print The Great Wave off Kanagawa in 1830 — part of the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji — he was 70 years old and had lived his entire life in a Japan closed off from the rest of the world. In the 19th century, however, “the rest of the world was becoming industrialized,” James Payne explains above in his Great Art Explained video, “and the Japanese were concerned about foreign invasions.” The Great Wave shows “an image of Japan fearful that the sea — which has protected its peaceful isolation for so long — would become its downfall.” It’s also true, however, that The Great Wave would not have existed without a foreign invasion. Prussian blue, the first stable blue pigment, accidentally invented around 1705 in Berlin, arrived in the ports of Nagasaki on Dutch and Chinese ships in the 1820s. Prussian Blue would start a new artistic movement in Japan, aizuri-e, woodcuts printed in bright, vivid blues. “Hokusai was one of the first Japanese printmakers to boldly embrace the colour,” Hugh Davies writes at The Conversation, “a decision that would have major implications in the world of art.” When the country’s isolationist policies ended in the 1850s, “a showcase at the inaugural Japanese Pavilion elevated the artistic status of woodblock prints and a craze for their collection quickly followed.”

Chief among the works collected in the European and American fervor for Japanese prints were those from Hokusai, his contemporary Hiroshige, and other aizuri-e artists. So famous was The Great Wave in the West by 1891 that French graphic artist Pierre Bonnard would satirize its stylish spray in an advertisement for champagne. A print of The Great Wave hung on Claude Debussy’s wall, and the first edition of his La Mer bore an adaptation of a detail from the print. As Michael Cirigliano writes for the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

These comparisons are not misplaced, John-Paul Stonard explains in The Guardian: “That the Great Wave became the best known print in the west was in large part due to Hokusai’s formative experience of European art.” Not only did he absorb Prussian blue into his repertoire, but “prints from early in his career show him attempting, rather awkwardly, to apply the lesson of mathematical perspective, learnt from European prints brought into Japan by Dutch Traders.” By the time of The Great Wave, he had perfected his own synthesis of Western and Japanese art, over two decades before European painters would attempt the same in the explosion of Japanophilia of the late 19th and early 20th century. Related Content: Watch the Making of Japanese Woodblock Prints, from Start to Finish, by a Longtime Tokyo Printmaker Watch the Making of Japanese Woodblock Prints, from Start to Finish, by a Longtime Tokyo Printmaker Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Great Wave Off Kanagawa by Hokusai: An Introduction to the Iconic Japanese Woodblock Print in 17 Minutes is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

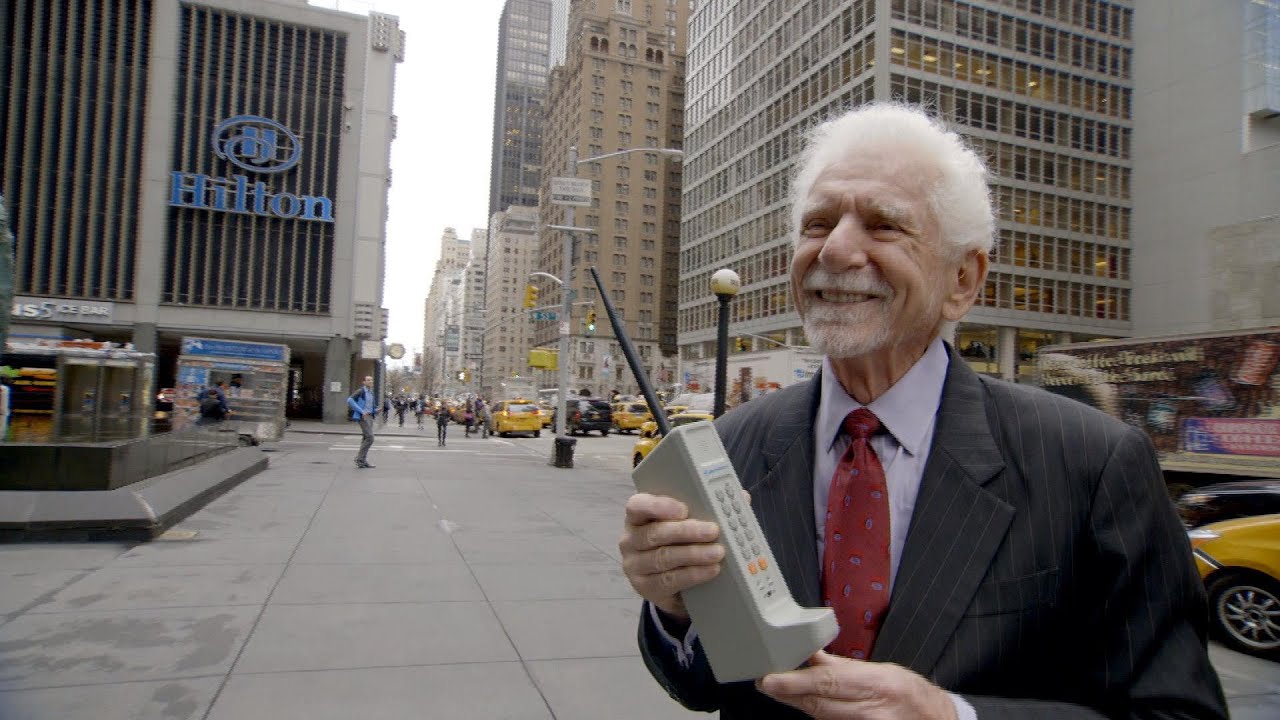

| 11:00a | The First Cellphone: Discover Motorola’s DynaTAC 8000X, a 2-Pound Brick Priced at $3,995 (1984) We get the culture our technology permits, and in the 21st century no technological development has changed culture like that of the smartphone. As with every piece of personal technology that we struggle to remember how we lived without, it evolved into being from a series of simpler predecessors that, no matter how clunky they seem now, were received as technological marvels in their day. Take it from Martin Cooper, the Motorola Engineer who invented the first handheld cellular mobile phone. “We didn’t know it was going to be historic in any way at all,” he says of the first publicly demonstrated cellphone call in 1973 in the Bloomberg video above. “We were only worried about one thing: is the phone going to work when we turn it on?” The device Cooper had in hand was the prototype that would eventually become the Motorola DynaTAC 8000X, the first commercial portable cellular phone. (This as distinct from the existing car-phone systems that Cooper credits with inspiring him to develop an entirely handheld version.) Brought to market in 1983, it weighed about two pounds, took ten hours to charge a battery that lasted only 30 minutes, could store no more than 30 phone numbers, and cost nearly $10,000 in today’s dollars. Yet “consumers were so impressed by the concept of being always accessible with a portable phone that waiting lists for the DynaTAC 8000X were in the thousands,” says Motorola design master Rudy Krolopp as quoted by the Project Management Institute. “In 1983, the notion of simply making wireless phone calls was revolutionary.”

38 years after “the brick,” as the 8000X was known, we’ve grown so used to that notion that many of us hardly ever make wireless phone calls anymore, preferring to communicate on our phones through text messages or an ever-expanding universe of internet-based apps — to say nothing of the other aspects of our lives increasingly handled through palm-sized touchscreens. “The modern smartphone is a technological marvel,” says Cooper. “It really is incredible, all the stuff that is squeezed into that cellphone.” Yet despite the astonishing evolution of his invention it represents, he’s not satisfied. “We think that we can make a smartphone that does all things for all people, and yet we know that it doesn’t do any of those things perfectly. We’ve still got a ways to go.” If you’re reading this on a smartphone, know that you hold in your hand the “brick” of 2059. Related Content: Filmmaker Wim Wenders Explains How Mobile Phones Have Killed Photography A 1947 French Film Accurately Predicted Our 21st-Century Addiction to Smartphones When We All Have Pocket Telephones (1923) The World’s First Mobile Phone Shown in 1922 Vintage Film Scientist Creates a Working Rotary Cellphone Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The First Cellphone: Discover Motorola’s DynaTAC 8000X, a 2-Pound Brick Priced at $3,995 (1984) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | A Young Janis Joplin Plays a Passionate Set at One of Her First Gigs in San Francisco (1963) From her early, unhappy teen years in Port Arthur, Texas, Janis Joplin seemed to know she wanted to be a blues singer. She once said she decided to become a singer when a friend “loaned her his Bessie Smith and Leadbelly records,” writes biographer Ellis Amburn. “Ten years later, Janis was hailed as the premier blues singer of her time. She paid tribute to Bessie by buying her a headstone for her unmarked grave.” She was devoted to the blues, from her earliest encounters with the music in her youth to her last recorded song, the lonely, a capella blues, “Mercedes Benz.” But when Joplin first appeared on the San Francisco scene in 1963, she did so as a Dylan-influenced folkie fresh from the University of Texas, Austin. The year before, she had been described by a profile in The Daily Texan as an artist who “goes barefooted when she feels like it, wears Levis to class because they’re more comfortable, and carries her autoharp with her everywhere she goes so that in case she gets the urge to break into song, it will be handy.” The article was titled “She Dares to Be Different.” Joplin’s folk persona was hardly unique in either San Francisco or Austin in the early 60s. “In fact, her love of Dylan and folk simply marked her out as a rider of the zeitgeist,” writes music journalist Chris Salewicz. “When, for example, a former University of Texas alumnus called Chet Helms passed through [Austin] he was astonished at the wealth of folk music.” Helms, who had already moved west, promised Joplin gigs in San Francisco. The pair hitchhiked to the city “midway through January 1963, with considerable trepidation… a trek in which they spent 50 hours on the road.” Once in North Beach, a neighborhood defined by City Lights bookstore and the Beats, Helms found Joplin gigs at Coffee and Confusion, then the Coffee Gallery, where she “was just one of many future rockers to play the Coffee Gallery as a folkie,” writes Alice Echols. In South Bay coffeehouses, she met Jerry Garcia and future Jefferson Airplane guitarist Jorma Kaukonen. Everyone made the coffeehouse rounds, acoustic guitar in hand. It was the way to make a name in the scene, which Janis did quickly, appearing the same year she arrived in San Francisco on the side stage at the Monterey Folk Festival. But Janis brought something different than other students of Dylan — bigger and bolder and louder and deeply rooted in a Southern blues tradition Joplin spread to astonished beatniks like a “Blues Historian,” one commenter notes, “turning a small audience on to some obscure and forgotten performers, whose music would serve as the foundation for an entire genre yet to come.” You can hear her do just that in the gig above at the Coffee Gallery in 1963: “no drums, no crowds. Just Janis and a small group of people gathered to hear some samples of rural blues, done by an enthusiast from Texas.” See the full setlist below. Other performers on the recording, according to the YouTube uploader, are Larry Hanks on acoustic guitar and vocals, and Billy Roberts (or possibly Roger Perkins) on acoustic guitar, as well as banjo, vocals, and harmonica.

Related Content: Janis Joplin’s Last TV Performance & Interview: The Dick Cavett Show (1970) Janis Joplin & Tom Jones Bring the House Down in an Unlikely Duet of “Raise Your Hand” (1969) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness A Young Janis Joplin Plays a Passionate Set at One of Her First Gigs in San Francisco (1963) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/05/20 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |