[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, July 21st, 2021

| Time | Event |

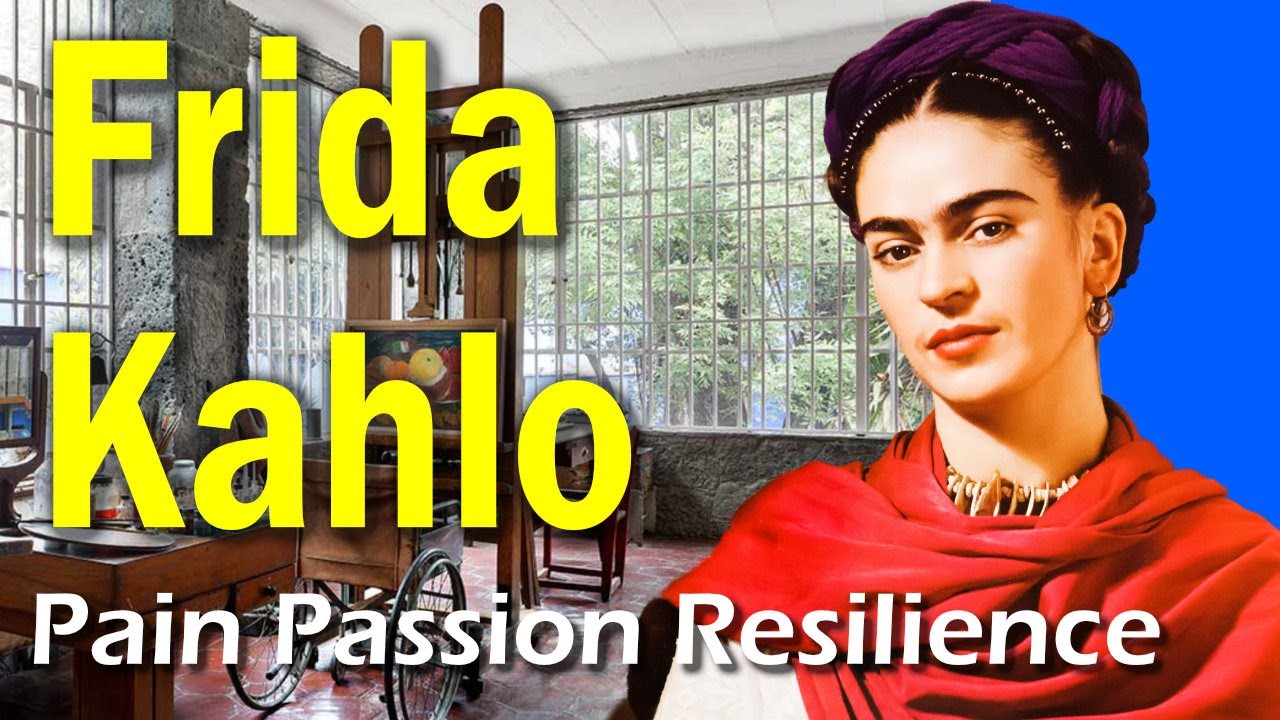

| 8:00a | Frida Kahlo: The Life of an Artist   Frida Kahlo has been a martyr to art history. Her twinned self-portrait The Two Fridas sits at number 87 on a list of the 100 most popular paintings (behind Diego Rivera’s The Flower Carrier and Cassius Coolidge’s Dogs Playing Poker series). She is “one of the most iconic and contradictory cultural figures around,” Judy Cox writes: “a card-carrying Communist whose image adorned a bracelet worn by Theresa May, a feminist who has her own barbie doll.” Her cultural credentials sell. Her work is acclaimed as a leading example of indigenismo, as Denver art museum senior curatorial assistant Jesse Laird Ortega writes, “a political, intellectual, and artistic movement that celebrated indigenous peoples in Mexico.” Kahlo herself is lauded as “a passionate nationalist who advocated for the revolution… and supported farmers and workers.” This praise sounds suspicious to other critics. “Missing from the public discourse about the artist are discussions about how the ‘nationalism’ that Kahlo promoted,” Joanna Garcia Cheran argues, “both in her art and personal style perpetuated the construction of a mythologized Indianness at the expense of Indigenous people.” Kahlo only began wearing the rebozos and other indigenous fashions she made famous when she married Diego Rivera (for the first time) in 1929. Does Paul Priestly, the host of the Art History School video lesson above, help smooth out the contradictions of Kahlo’s life and art? No, but to be fair, he makes no pretense to higher criticism. The lesson is a basic introduction (with a content warning for younger viewers) to the well-known facts of Frida’s life, those amply covered in documentaries like Ken Madel’s Frida Kahlo: A Ribbon Around a Bomb and (with plenty of dramatic license, of course) the Salma Hayek-starring biopic Frida. Priestley’s video is a sound introduction to Kahlo’s life, however, precisely because it shies away from hagiography or theory. He walks us through the facts of the artist’s life in brief, with clips of a woman reading Frida’s own words and images of her work alongside photographic portraits of herself at every stage of life, allowing viewers to see the side-by-side development of Kahlo’s art and her public persona. In the midst of Kahlo worship and iconoclasm, what seems too often neglected is Kahlo’s complex humanity. She was not one thing or another — neither wholly Marxist saint, nor a bourgeois appropriator; neither wholly feminist hero, nor tragic victim of patriarchal male hero worship: she was both and neither, at many times, a figure twinned in her imagination and split in half by cultural logics that want to claim and possess art and artists for their own. Related Content: Take a Virtual Tour of Frida Kahlo’s Blue House Free Online Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Frida Kahlo: The Life of an Artist is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | Explore Divine Comedy Digital, a New Digital Database That Collects Seven Centuries of Art Inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy

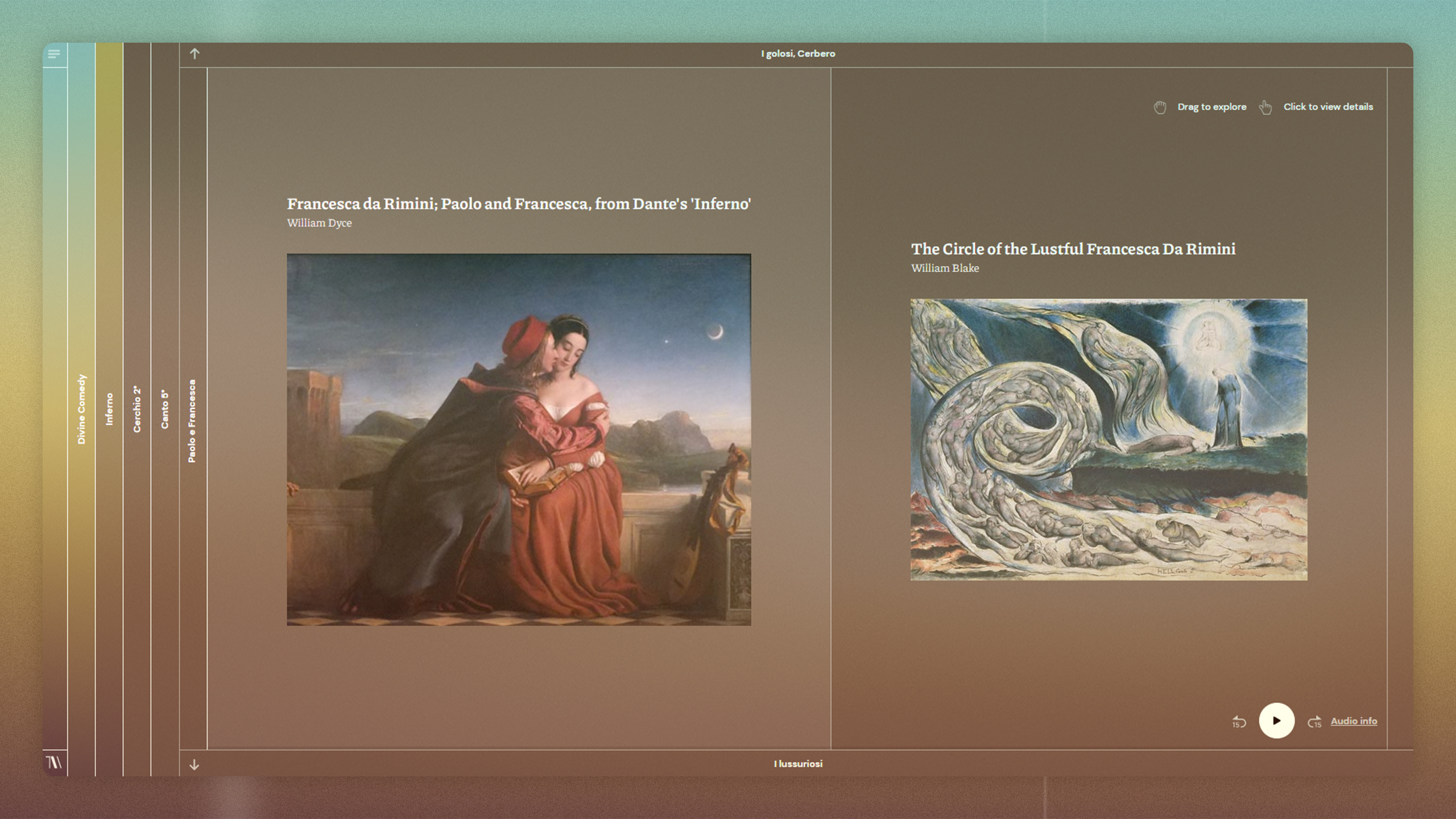

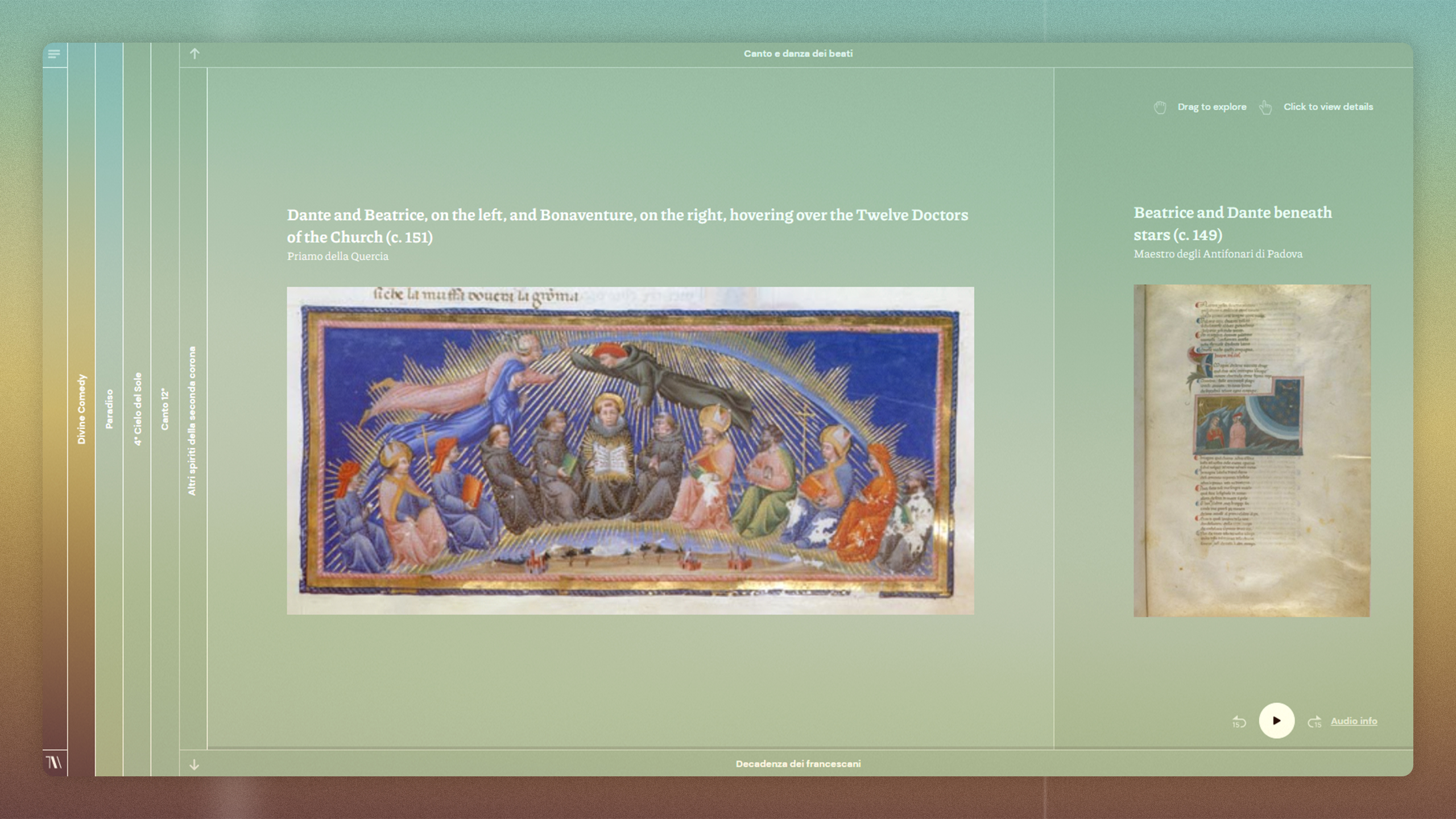

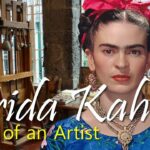

The number of artworks inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy in the seven hundred years since the poet completed his epic, vernacular masterwork is so vast that referring to the poem inevitably means referring to its illustrations. These began appearing decades after the poet’s death, and they have not stopped appearing since. Indeed, it might be fair to say that the title Divine Comedy (simply called Comedy before 1555) names not only an epic poem but also its many constellations of artworks and interpretations, which would have filled a modest-sized set of Dante encyclopedias before the internet.

Luckily for art historians and Dante scholars working today, there is now Divine Comedy Digital, a beautifully designed database which brings these artworks — spread out all over the world — together in one virtual place. The interface requires no special Dante knowledge to navigate, though it helps to be familiar with the poem and/or have a reference copy nearby when looking through the menus. Dividing neatly into the poem’s three books (or cantiche), the menu at the left further breaks down into circles (Inferno), terraces (Purgatorio), and Cantos (all three books).

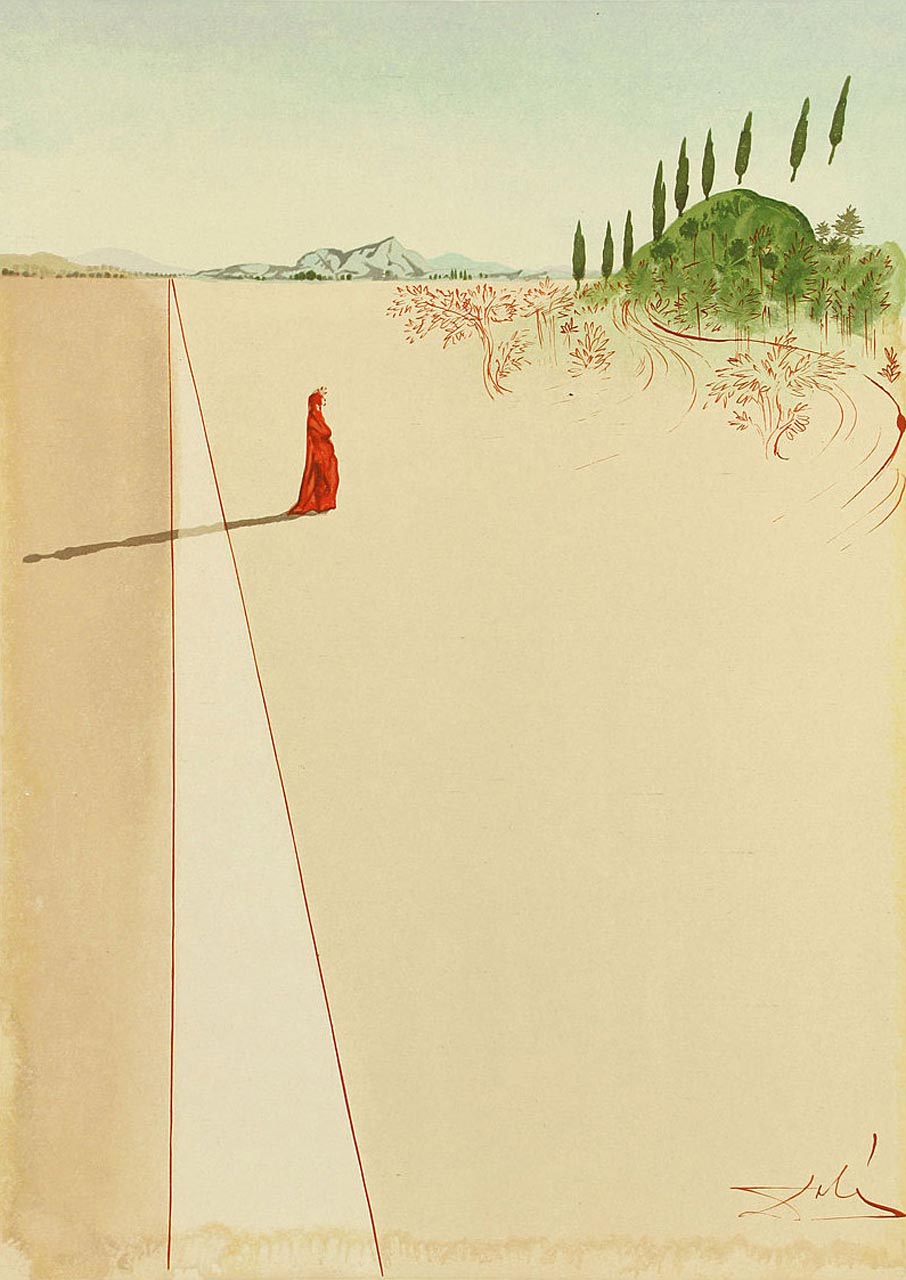

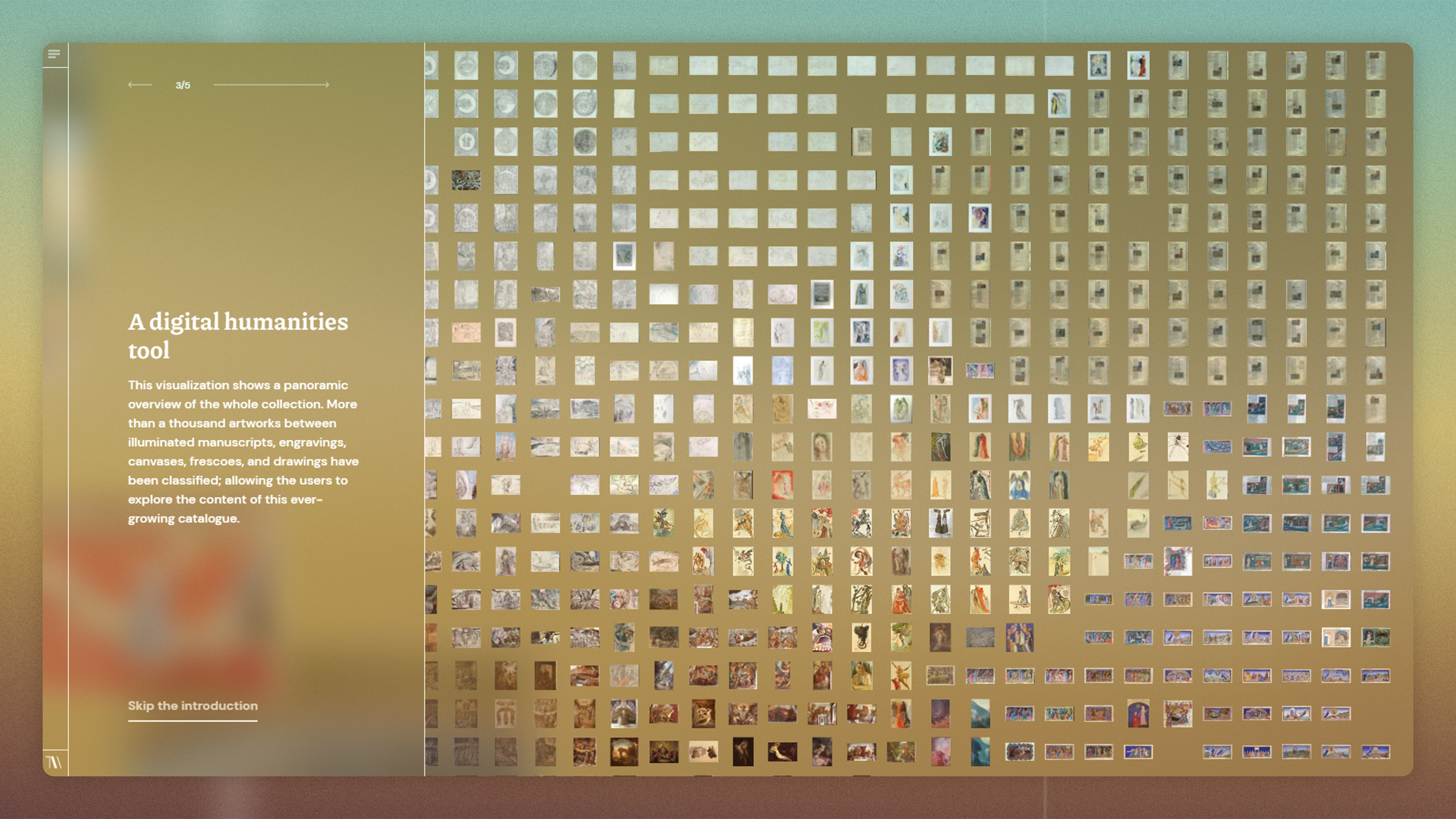

Toggling between options in a menu on the right allows visitors to see the number of illustrated verses in each Canto or the number of artworks. Within a matter of minutes, you’ll be discovering Dante illustrations you never knew existed, from Salvador Dali’s The Delightful Mount (1950, above) to Alessandro Vellutello’s Dante and St. Bernard, Mary and the Trinity (1544) and hundreds of others in the years in-between.

Calling itself a “slow surfing site,” Divine Comedy Digital contains a handy tutorial if you do get lost and allows users “not only to navigate through the collection, but also to suggest missing artworks.” So far, the 17th and 18th centuries are hugely underrepresented, though not for a lack of Dante-inspired artwork made in that two-hundred year period. The gaps mean there is much more Dante art to come.

Released in June of this year, the project is the work of The Visual Agency, “an information design agency specialized in data-visualization based in Milan and Dubai” and was created to celebrate the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death. As he continues to inspire artists for the next few hundred years, perhaps the work based on his epic poem will trend more digital than medieval, creating interpretations the poet never could have dreamt. Enter the Divine Comedy Digital project here. You can also see some of the earliest illustrated editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1487-1568), courtesy of Columbia University, here.

Related Content: A Free Course on Dante’s Divine Comedy from Yale University Mœbius Illustrates Dante’s Paradiso Artists Illustrate Dante’s Divine Comedy Through the Ages: Doré, Blake, Botticelli, Mœbius & More Visualizing Dante’s Hell: See Maps & Drawings of Dante’s Inferno from the Renaissance Through Today Hear Dante’s Inferno Read Aloud by Influential Poet & Translator John Ciardi (1954) A Digital Archive of the Earliest Illustrated Editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1487-1568) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness. Explore Divine Comedy Digital, a New Digital Database That Collects Seven Centuries of Art Inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:10p | The Aesthetic of Evil: A Video Essay Explores Evil in the Films of Bergman, Hitchcock, Kubrick, Scorsese & Beyond   Movies have heroes and villains. Or at least children’s movies do; the more sophisticated the audience, the hazier the line between good and evil becomes, until it finally seems to vanish altogether. Not that cinema directed toward genuinely mature audiences dispenses with those concepts entirely: rather, it makes art out of the ambiguity and interpenetration between them. This is true, to an extent, even in some of the recent wave of big-budget superhero movies, in the main exercises in rolling an “adult” texture onto stories essentially geared toward adolescents. Hence the appearance of the Joker, Batman’s grinning arch-nemesis, in “The Aesthetic of Evil,” the Cinema Cartography video essay above. In the Joker of Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight, “we see an evil that’s relentless, primarily because the core function is complete and total anarchy. Whatever order is established, whoever it’s under ,must be destroyed. As a result, an epoch is created where any rules or codes of conduct are broken. Anything that you anticipate will happen, will result in the opposite.” This Joker made an outsized cultural impact with not just the explicitness of his disorder-oriented morality, but also a material-transcending performance by Heath Ledger. In that same era, Jamie Hector took a comparatively minimalist but equally memorable turn in David Simon’s series The Wire as Marlo Stanfield, a drug kingpin “too villainous for the villains.” Like the Joker, Marlo is a law unto himself, “willing to destroy the equilibrium of any facet of the world there is, on a whim.” These two represent just one of the forms evil has taken in recent decades. The essay’s other examples range from Psycho‘s Norman Bates and 2001’s HAL 9000 to The King of Comedy‘s Rupert Pupkin and Fanny and Alexander‘s stepfather Edvard — or rather, the unwelcome transformation of the family Edvard represents. The most diabolical evil does not confine itself within the person of the antagonist, especially not in the work of Michael Haneke, which twice appears in “The Aesthetic of Evil.” Benny’s Video is on one level about a murderous adolescent; on another, it’s about the “evasion of the real” that seduces us all. The White Ribbon is on one level about random acts of violence in a small village; on another, it’s about how evil reflects “the collective consciousness of a society.” Haneke’s films have often been described as difficult to watch, and that may well have less to do with what they show than what they know: even if we aren’t all villains, we’re certainly not heroes. Related Content: Orson Welles on the Art of Acting: ‘There is a Villain in Each of Us’ Rare Video: Georges Bataille Talks About Literature & Evil in His Only TV Interview (1958) The Aesthetic of Anime: A New Video Essay Explores a Rich Tradition of Japanese Animation The Dark Knight: Anatomy of a Flawed Action Scene Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The Aesthetic of Evil: A Video Essay Explores Evil in the Films of Bergman, Hitchcock, Kubrick, Scorsese & Beyond is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/07/21 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |