[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, July 22nd, 2021

- Alleged, a short about dramatizing accusations against Steven Segal

- Inside You, a film she wrote, directed, and (reluctantly) starred in

- The Focus Group, a short Heather directed written by and starring Sara Benincasa

- “Directing Comedy 101” by Ray Richmond

- “Judd Apatow Talks to Jason Bateman About Being the ‘Anti-David Fincher’ | Directors on Directors”

- “10 Best Contemporary Comedy Directors” by Rafael Sarmiento

- “The Best Comedy Directors in Film History” from Ranker

- “10 Hollywood notables who directed an episode of ‘The Office’” by Mike Rose

| Time | Event |

| 7:01a | What’s the Role of a Director in Constructing Comedy? Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #100

What makes for a good comedy film or show? Funny people reading (or improvising) funny lines is not enough; an good director needs to capture (or recreate in the editing room) comic timing, construct shots so that the humor comes through and coach the actors to make sure that the tone of the work is consistent. Your Pretty Much Pop hosts Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt are joined by Heather Fink to discuss the role of the director in making a comedy (or anything else) actually good. Heather has directed for TV, film, and commercials and spent a lot of time doing sound (a boom operator or sound utility) for productions like Saturday Night Live, Get Out, The Morning Show, and Marvel’s Daredevil. We talk about maintaining comedy through the tedious process of filming, putting actors through sex scenes and other hardships, not telling them how to say their lines, comedians in dramas, directing improv/prank shows, and more. We touch on include Bad Trip, Barry, and Ted Lasso, and more. Watch some of Heather’s work: We used some articles to bring various directors and techniques to mind: Hear more of this podcast at prettymuchpop.com. This episode includes bonus discussion that you can access by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts. What’s the Role of a Director in Constructing Comedy? Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #100 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:06a | When David Bowie Played Andy Warhol in Julian Schnabel’s Film, Basquiat Many actors have played Andy Warhol over the years, but not as many as you might think. Crispin Glover played him in The Doors, Jared Harris played him in I Shot Andy Warhol, Guy Pearce played him in Factory Girl, and Bill Hader played him in Men in Black III, but with a twist: he is actually an agent who is so bad as his cover role as an artist, he’s “painting soup cans and bananas, for Christ sakes!” On television John Cameron Mitchell has acted the Warhol role in Vinyl, and Evan Peters briefly portrayed him in American Horror Story: Cult. But you might suspect our favorite Warhol would be the one acted by David Bowie in Julian Schnabel’s 1996 Basquiat, the biopic of the Black street artist who was taken into the art world fold by Warhol, and wound up collaborating with him in last works by both artists. Jeffrey Wright plays Basquiat in one of his earliest roles. Now, you might watch this scene from Basquiat above (and another below) and say, well, that’s just mostly Bowie. But I would say, yes, that’s kind of the point. Andy Warhol is an enigmatic figure, a legend to many, a man who hid behind a constructed persona; David Bowie is too. When one plays the other, a weird sort of magic happens. Fame leaks into fame. Many actors might do better with the mannerisms or the voice, but the charisma…that is all Bowie. After singing about the painter back in 1972, Bowie finally collapsed their visions together in the art of film, where reality and fantasy meet and meld. Around this time in the mid 1990s, Bowie was very much a part of the New York/London art scene. He was on the editorial board of Modern Painters magazine and interviewed Basquiat director (and artist) Julian Schnabel, Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst, and Balthus. A conceptual artist-slash-serial killer became one of the main characters of his overlooked 1995 Eno collaboration Outside. He was both a collector and an artist, which we’ve focused on before. And he was thinking about the new world opening up because of the internet. Bowie’s artist brain saw the possibilities and the dangers, and also the raw capitalist potential. He offered shares in himself as an IPO in 1997 and released a single as Tao Jones Index, three puns in one. Bowie never predicted the idiocy of the NFT, but he certainly would have laughed wryly at it. In this Charlie Rose interview to promote Basquiat, Bowie and Schnabel discuss the role of Warhol, the role of art, and the reality of the art world. “It was more of an impersonation, really,” says Bowie about his Warhol. “That’s how I approach anything.” Of note, however, is how quickly Bowie moves away from discussing himself or the film to talk about larger issues of art and commerce. Bowie does admit that he and Schnabel disagree on a lot of things, and you can see it in their body language. But there’s also a huge respect. It’s a fascinating interview, go watch the whole thing. Bonus: Below watch Bowie meeting Warhol back during the day… Related Content: 96 Drawings of David Bowie by the “World’s Best Comic Artists”: Michel Gondry, Kate Beaton & More The Odd Couple: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol, 1986 When David Bowie Launched His Own Internet Service Provider: The Rise and Fall of BowieNet (1998) Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here. When David Bowie Played Andy Warhol in Julian Schnabel’s Film, Basquiat is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

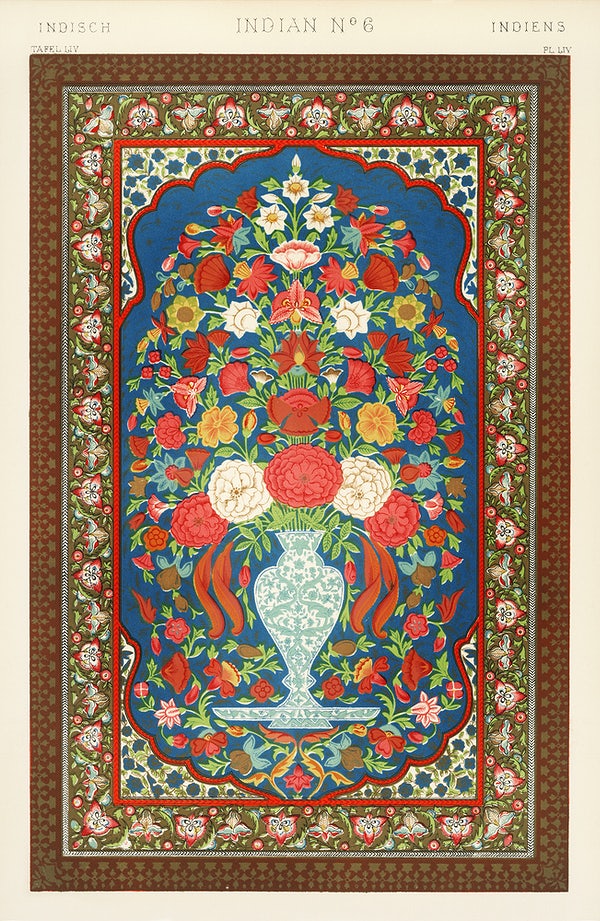

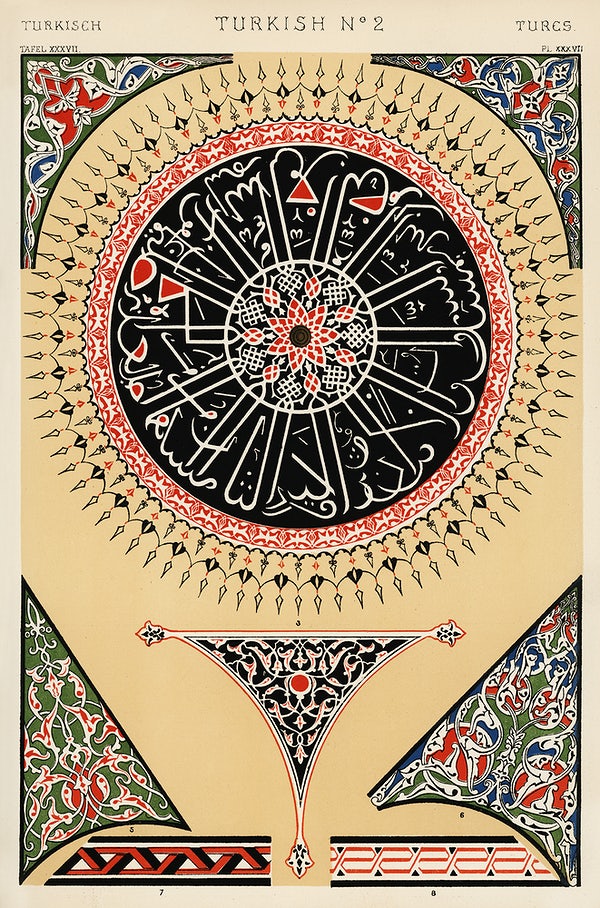

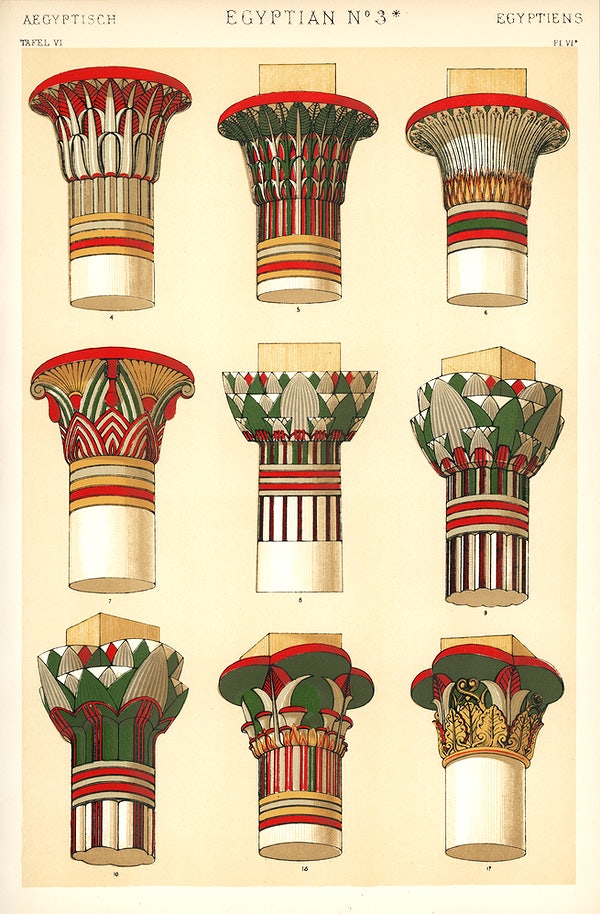

| 11:00a | Discover The Grammar of Ornament, One of the Great Color Books & Design Masterpieces of the 19th Century In the mid-17th century, young Englishmen of means began to mark their coming of age with a “Grand Tour” across the Continent and even beyond. This allowed them to take in the elements of their civilizational heritage first-hand, especially the artifacts of classical antiquity and the Renaissance. After completing his architectural studies, a Londoner named Owen Jones embarked upon his own Grand Tour in 1832, rather late in the history of the tradition, but ideal timing for the research that inspired the project that would become his legacy.

According to the Victoria and Albert Museum, Jones visited “Italy, Greece, Egypt and Turkey before arriving in Granada, in Spain to carry out studies of the Alhambra Palace that were to cement his reputation.” He and French architect Jules Goury, “the first to study the Alhambra as a masterpiece of Islamic design,” produced “hundreds of drawings and plaster casts” of the historical, cultural, and aesthetic palimpsest of a building complex. The fruit of their labors was the book Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the Alhambra, “one of the most influential publications on Islamic architecture of all time.”

Published in the 1840s, the book pushed the printing technologies of the day to their limits. In search of a way to do justice to “the intricate and brightly colored decoration of the Alhambra Palace,” Jones had to put in more work researching “the then new technique of chromolithography — a method of producing multi-color prints using chemicals.” In the following decade, he would make even more ambitious use of chromolithography — and draw from a much wider swath of world culture — to create his printed magnum opus, The Grammar of Ornament.

With this book, Jones “set out to reacquaint his colleagues with the underlying principles that made art beautiful,” write Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Femke Speelberg and librarian Robyn Fleming. “Instead of writing an academic treatise on the subject, he chose to assemble a book of one hundred plates illustrating objects and patterns from around the world and across time, from which these principles could be distilled.” To accomplish this he drew on his own travel experiences as well as resources closer at hand, including “the museological and private collections that were available to him in England, and the objects that had been on display during the Universal Exhibitions held in London in 1851 and 1855.”

The Grammar of Ornament was published in 1856, emerging into a Britain “dominated by historical revivals such as Neoclassicism and the Gothic Revival,” says the V&A. “These design movements were riddled with religious and social connotations. Instead, Owen Jones sought a modern style with none of this cultural baggage. Setting out to identify the common principles behind the best examples of historical ornament, he formulated a design language that was suitable for the modern world, one which could be applied equally to wallpapers, textiles, furniture, metalwork and interiors.”

Indeed, the patterns so lavishly reproduced in the book soon became trends in real-world design. They weren’t always employed with the intellectual understanding Jones sought to instill, but since The Grammar of Ornament has never gone out of print (and can even be downloaded free from the Internet Archive), his principles remain available for all to learn — and his painstakingly artistic printing work remains available for all to admire — even in the corners of the world that lay beyond his imagination. You can purchase a complete and unabridged color edition of The Grammar of Ornament online. Related Content: The Complex Geometry of Islamic Art & Design: A Short Introduction A Beautiful 1897 Illustrated Book Shows How Flowers Become Art Nouveau Designs Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Discover The Grammar of Ornament, One of the Great Color Books & Design Masterpieces of the 19th Century is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Oldest-Known Work of Literature in World History You’re probably familiar with The Epic of Gilgamesh, the story of an overbearing Sumerian king and demi-god who meets his match in wild man Enkidu. Gilgamesh is humbled, the two become best friends, kill the forest guardian Humbaba, and face down spurned goddess Ishtar’s Bull of Heaven. When Enkidu dies, Gilgamesh goes looking for the only man to live forever, a survivor of a legendary pre-Biblical flood. The great king then tries, and fails, to gain eternal life himself. The story is packed with episodes of sex and violence, like the modern-day comics that are modeled on ancient mythology. It is also, as you may know, the oldest-known work of literature on Earth, written in cuneiform, the oldest-known form of writing. This is one version of the story. But Gilgamesh beaks out of the tidy frame usually put around it. It is a “poem that exists in a pile of broken pieces,” Joan Acocella writes at The New Yorker, “in an extremely dead language.” If Gilgamesh were based on a real king of Ur, he would have lived around 2700 BC. The first stories written about him come from some 800 years after that time, during the Old Babylonian period, after the last of the Sumerian dynasties had already ended. The version we tend to read in world literature and mythology courses comes from several hundred years later, notes the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Ira Spar:

This so-called “Standard Babylonian Version,” as you’ll learn in the TED-Ed video at the top by Soraya Field Fiorio, was itself only discovered in 1849 — very recent by comparison with other ancient texts we regularly read and study. The first archaeologists to discover it were searching not for Sumerian literature but for evidence that proved the Biblical stories. They thought they’d found it in Nineveh, in the excavated library of King Ashurbanipal, the oldest library in the world. Instead, they discovered the broken, incomplete tablets containing the story of Gilgamesh and Utnapishtim, who, like Noah from the Hebrew Bible, built an enormous boat in advance of a divinely ordered flood. The first person to translate the passages was so excited, he stripped off his clothes. The flood story wasn’t the knock-down proof Christian scholars hoped for, but the discovery of the Gilgamesh epic was even more important for our understanding of the ancient world. What we know of the story, however, was already edited and redacted to suit a millennia-old agenda. The Epic of Gilgamesh “explains that Gilgamesh, although he is king of Uruk, acts as an arrogant, impulsive, and irresponsible ruler,” Spar writes. “Only after a frustrating and vain attempt to find eternal life does he emerge from immaturity to realize that one’s achievements, rather than immortality, serve as an enduring legacy.” Other, much older versions of his story show the mythical king and his exploits in a different light. So how should we read Gilgamesh in the 21st century, a few thousand years after his first stories were composed? You can begin here with the TED-Ed summary and Crash Course in World Mythology video further up. Dig much deeper with the lecture above from Andrew George, Professor of Babylonian at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). George has produced one of the most highly respected translations of Gilgamesh, Acocella writes, one that “gives what remains of Sin-leqi-unninni’s text” and appends other fragmentary tablets discovered in Baghdad, showing how the meaning of the cuneiform symbols changed over the course of the millennia between the Old Babylonian stories and the “New Babylonian Version” of the Epic of Gilgamesh we think we know. Hear a full reading of Gilgamesh above, as translated by N.K. Sanders. Related Content: Hear The Epic of Gilgamesh Read in its Original Ancient Language, Akkadian 20 New Lines from The Epic of Gilgamesh Discovered in Iraq, Adding New Details to the Story World Literature in 13 Parts: From Gilgamesh to García Márquez Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Oldest-Known Work of Literature in World History is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/07/22 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |