[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, August 4th, 2021

- Functionally, individuals entertain themselves with a variety of things; they are our cultural food, and can include many obsessions that have nothing to do with manufactured media at all. If such fascinations are also used by multiple people to bond over, then that’s culture, and insofar as bonding over that object is common, then it’s pop culture.

- There’s a continuum between creation and spectating. Creators are first of all consumers and create largely through imitating and tweaking past works. Though this podcast focuses largely on the consumer side of the equation, some of audience appreciation is a matter of respect for the craft, which increases through understanding and (at least vicarious) participation in the activity. Though it’s not always the case that we get enjoyment through sympathy with the artistic choices a creator makes (sometimes we just marvel uncomprehendingly), this is a significant dynamic in fandom. Viewers who liked Game of Thrones had many ideas about how it should have ended even if they had no opportunity or even talent to really provide an alternative.

| Time | Event |

| 7:01a | Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast — Season One Wrap: What Have We Learned? (#102)

After 101 episodes and a bit over two years, OpenCulture’s first podcast offering is moving into a new phase. Here your hosts Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian hirt reflect on what we’ve learned and set a course for the future. Our overarching concern with this podcast has been how and why we consume. We may not have learned a great deal about this issue in a general sense, but we’ve certainly been shown the appeal of many forms that we might not have considered before, and we’ve theorized about why people like drama or horror, or what makes for compelling sci-fi or gaming, etc. We’ve stretched over these episodes into some unexpected areas for a pop culture podcast, like the philosophy of photography and why people obsess over conspiracy theories. The current discussion takes this on through a re-consideration of what pop culture is. Of course, the title of the podcast has “pretty much” in it, which allows a certain amount of leeway, but the source of that ambiguity is not just that I want the freedom to bring in any topic that interests me, but because of two points covered in this episode: It all comes down to the dimensions of mimesis, which means reflection. We enjoy storytelling largely because it reflects us, either how we are, how we might like to be, or how we fear we could be. We get some of our ideas about who we are from these media reflections. Marketers guess at who they think we are (again, in part based on media) and create products to market at us. Artists create works reflected from other works which attempt to reflect us (or distort us based on knowledge of a reflection). Who we are as a culture may be very much storytelling all the way down. So political myths are an essential part of this, as are sexual mores, ideas about what leisure activities (and jobs, for that matter) are respectable, manners taken more generally, how we deal with our legacies of racism and sexism, what we find funny and how that changes over time, and much much more. Thanks, all, for listening. We’ll be back in a few weeks. This episode includes bonus discussion you can access by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast — Season One Wrap: What Have We Learned? (#102) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00a | Carl Jung Offers an Introduction to His Psychological Thought in a 3-Hour Interview (1957) In the 1950s, it was fashionable to drop Freud’s name — often as not in pseudo-intellectual sex jokes. Freud’s preoccupations had as much to do with his fame as the actual practice of psychotherapy, and it was assumed — and still is to a great degree — that Freud had “won” the debate with his former student and friend Carl Jung, who saw religion, psychedelic drugs, occult practices, etc. as valid forms of individualizing and integrating human selves — selves that were after all, he thought, connected by far more than biological drives for sex and death. Now Jung’s insights permeate the culture, in increasingly popular fields like transpersonal psychology, for example, that see humans as “radically interconnected, not just isolated individuals,” psychologist Harris L. Friedman argues. Movements like these grew out of the “counterculture movements of the 1960s,” psychology lecturer and author Steve Taylor explains, “and the wave of psycho-experimentation it involved, through psychedelic substances, meditation and other consciousness changing practices” — the very practices Jung explored in his work. Indeed, Jung was the first “to legitimize a spiritual approach to the practice of depth psychology,” Mark Kasprow and Bruce Scotton point out, and “suggested that psychological development extends to include higher states of consciousness and can continue throughout life, rather than stop with the attainment of adult ego maturation.” Against Freud, who thought transcendence was regression, Jung “proposed that transcendent experience lies within and is accessible to everyone, and that the healing and growth stimulated by such experience often make use of the languages of symbolic imagery and nonverbal experience.” Jung’s work became increasingly important after his death in 1961, leading to the publication of his collected works in 1969. These introduced readers to all of his “key concepts and ideas, from archetypal symbols to analytical psychology to UFOs,” notes a companion guide. Near the end of his life, Jung himself provided a verbal survey of his life’s work in the form of four one-hour interviews conducted in 1957 by University of Houston’s Dr. Richard Evans at the Eidgenossische Technische Hoschschule (Federal Institute of Technology) in Zurich. “The conversations were filmed as part of an educational project designed for students of the psychology department. Evans is a poor interviewer, but Jung compensates well,” the Gnostic Society Library writes. The edited interviews begin with a question about Jung’s concept of persona (also, incidentally, the theme and title of Ingmar Bergman’s 1966 masterpiece). In response, Jung describes the persona in plain terms and with everyday examples as a fictional self “partially dictated by society and partially dictated by the expectations or the wishes one nurses oneself.” The less we’re consciously aware of our public selves as performances in these terms, the more we’re prone, Jung says, to neuroses, as the pressure of our “shadow,” exerts itself. Jung and Evans’ discussion of persona only grazes the surface of their wide-ranging conversation about the unconscious and the many ways to access it. Throughout, Jung’s examples are clear and his explanations lucid. Above, you can see a transcribed video of the same interviews. Read a published transcript in the collection C.G. Jung Speaking, and see more Jung interviews and documentaries at the Gnostic Society Library. Related Content: Zen Master Alan Watts Explains What Made Carl Jung Such an Influential Thinker The Visionary Mystical Art of Carl Jung: See Illustrated Pages from The Red Book How Carl Jung Inspired the Creation of Alcoholics Anonymous Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Carl Jung Offers an Introduction to His Psychological Thought in a 3-Hour Interview (1957) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

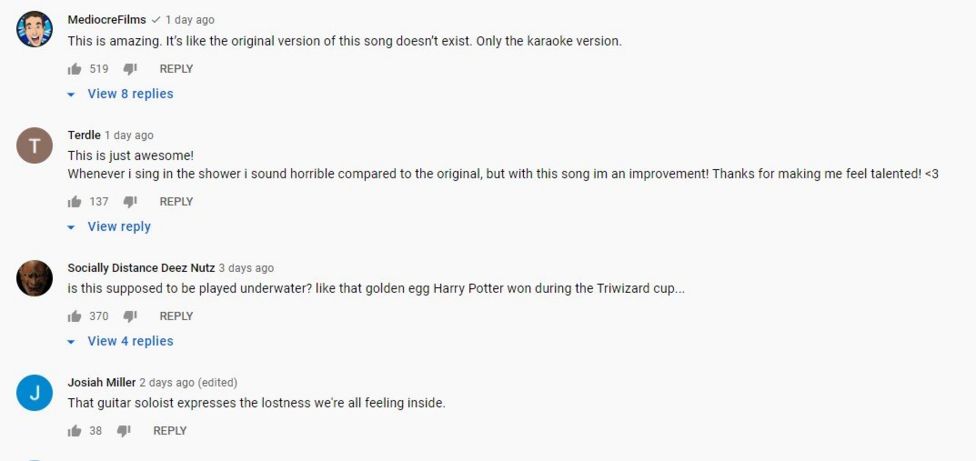

| 11:00a | Is the Viral “Red Dress” Music Video a Sociological Experiment? Performance Art? Or Something Else? Before it set itself on fire, HBO’s Game of Thrones resonated deeply with contemporary morality, becoming the most meme-worthy of shows, for good or ill, online. Few scenes in the show’s run — perhaps not even the Red Wedding or the nauseating finale — elicited as much gut-level reaction as Cersei Lannister’s naked walk of shame in the Season 5 finale, a scene all the more resonant as it happened to be based on real events. In 1483, one of King Edward IV’s many mistresses, Jane Shore, was marched through London’s streets by his brother Richard III, “while crowds of people watched, yelling and shaming her. She wasn’t totally naked,” notes Mental Floss, “but by the standards of the day, she might as well have been,” wearing nothing but a kirtle, a “thin shift of linen meant to be worn only as an undergarment.” What are the standards of our day? And what is the punishment for violating them? Sarah Brand seemed to be asking these questions when she posted “Red Dress,” a music video showcasing her less than stellar singing talents inside Oxford’s North Gate Church. In less than a month, the video has garnered well over half a million views, “impressive for a musician with hardly any social media footprint or fan base,” Kate Fowler writes at Newsweek. “It takes only a few seconds,” Fowler generously remarks, “to realize that Brand may not have the voice of an angel.” Or, as one clever commenter put it, “She is actually hitting all the notes… only of other songs. And at random.” Is she ludicrously un-self-aware, an heiress with delusions of grandeur, a sad casualty of celebrity culture, forcing herself into a role that doesn’t fit? Or does she know exactly what she’s doing… The judgments of medieval mobs have nothing on the internet, Brand suggests. “Red Dress” presents what she calls “a cinematic, holistic portrayal of judgment,” one that includes internet shaming in its calculations. Given the amount of online rancor and ridicule her video provoked, it “did what it set out to do,” she tells the BBC. And given that Brand is currently completing a master’s degree in sociology at Oxford University, many wonder if the project is a sociological experiment for credit. She isn’t saying.

Jane Shore’s walk ended with years locked in prison. Brand offered herself up for the scorn and hatred of the mobs. No one is pointing a pike at her back. She paid for the privilege of having people laugh at her, and she’s especially enjoying “some very, very witty comments” (like those above). She’s also very much aware that she is “no professional singer.”

All of this is voluntary performance art, in a sense, though Brand has shown previous aspirations on social media to become a singer, and perhaps faced similar ridicule involuntarily. “Part of what this project deals with,” she says, is judgment “overall as a central theme.” She credits herself as the director, producer, choreographer, and editor and made every creative decision, to the bemusement of the actors, crew, and studio musicians. Yet choosing to endure the gauntlet does not make the gauntlet less real, she suggests. The shame rained down on Shore was part misogyny, part pent-up rage over injustice directed at a hated better. When anyone can pretend (or pretend to pretend) to be a celebrity with a few hundred bucks for cinematography and audio production, the boundaries between our “betters” and ourselves get fuzzy. When young women are expected to become brands, to live up to celebrity levels of online polish for social recognition, self-expression, or employment, the lines between choice and compulsion blur. With whom do we identify in scenes of public shaming? Brand is coy in her summation. “Judgmental behavior does hurt the world,” she says, “and that is what I’m trying to bring to light with this project.” Judge for yourself in the video above and the … interesting… lyrics to “Red Dress” below.

Related Content: Hear the Experimental Music of the Dada Movement: Avant-Garde Sounds from a Century Ago Brian Eno Explains the Loss of Humanity in Modern Music Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Is the Viral “Red Dress” Music Video a Sociological Experiment? Performance Art? Or Something Else? is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 1:45p | When Mahatma Gandhi Met Charlie Chaplin (1931) Mahatma Gandhi and Charlie Chaplin were both forged in the 19th century, and both went on to become icons of the 20th. History has remembered one as a tireless liberator and the other as a tireless entertainer; decades after their deaths, both continue to command the respect of many in the 21st century. It’s understandable then, that a meeting between Gandhi and Chaplin at the peak of their fame would cause something of a fuss. “East-Enders, in the thousands, turn out to greet the two famous little men,” announces the title card of the British Pathé newsreel clip above. Cries of “Good old Charlie!” and “Good old Gandhi!” were heard. The occasion for this encounter was the Round Table Conferences, a series of meetings between the British government and political representatives of India held with an eye toward constitutional reform. “The buzz was that Mahatma Gandhi would be coming to Britain for the first time since he joined the Freedom movement,” writes blogger Vijayamadhav. The buzz proved correct, but more historic than the results of that particular conference session was what transpired thereafter. “Gandhi was preparing for his departure when a telegram reached him. A certain Charles Chaplin, who was in Britain at that time, had requested permission to be granted an audience with him.” Gandhi, said to have seen only two films in his life (one of them in Hindi), “did not know who this gentleman was,” and so “replied that it would be hard for him to find time and asked his aides to send a reply declining the request.” But it seems that Gandhi’s circle contained Chaplin fans, or at least advisors aware of the political value of a photo opportunity with the most beloved Englishman alive, who prevailed upon him to take the meeting. And so, on September 22, 1931, “hundreds of people crowded around the house” — the characteristically humble lodgings off East India Dock Road — “to catch a glimpse of the famous visitors.” Some “even clambered over garden fences to look through the windows.” Chaplin opened with a question to Gandhi about his “abhorrence of machinery.” Gandhi’s reply, as recorded in The Print: “Machinery in the past has made us dependent on England, and the only way we can rid ourselves of that dependency is to boycott all goods made by machinery,” especially those machines he saw as robbing Indians of their livelihoods. Chaplin later wrote of having received in this conversation “a lucid object lesson in tactical maneuvering in India’s fight for freedom, inspired, paradoxically, by a realistic, virile-minded visionary with a will of iron to carry it out.” He might also have got the idea for 1935’s Modern Times, a comedic critique of industrialized modernity that now ranks among Chaplin’s most acclaimed works. The abstemious Gandhi never saw it, of course, and whether it would have made him laugh is an open question. But apart, perhaps, from its glorification of drug use, he could hardly have disagreed with it. Related Content: Watch Gandhi Talk in His First Filmed Interview (1947) Mahatma Gandhi’s List of the 7 Social Sins; or Tips on How to Avoid Living the Bad Life Charlie Chaplin Does Cocaine and Saves the Day in Modern Times (1936) Watch 85,000 Historic Newsreel Films from British Pathé Free Online (1910-2008) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. When Mahatma Gandhi Met Charlie Chaplin (1931) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/08/04 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |