[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, August 12th, 2021

| Time | Event |

| 11:00a | Every Christmas, Peruvians Living in the Andes Settle Their Scores at Fist-Fighting Festivals As Chris Hedges discovered as a battle-hardened reporter, war is a force that gives us meaning. Whether we sublimate violence in entertainment, have paid professionals and state agents do it for us, or carry it out ourselves, human beings cannot seem to give up their most ancient vice; “we demonize the enemy,” Hedges wrote, “so that our opponent is no longer human,” and “we view ourselves, our people, as the embodiment of absolute goodness…. Each side reduces the other to objects — eventually in the form of corpses.” Each new generation inherits old hatreds, and so forth…. Maybe one way to break cycles of violence is with controlled violence — using bare fists to settle scores, and walking away with only bruises, a little hurt pride, but no lasting wounds? That’s the idea behind Takanakuy, an Andean festival that takes place each year at Christmas in the province of Chumbivilcas, in the mountains of Peru. The region has a police force made up of around three officers, the nearest courthouse is “a stomach-wrecking 10-hour drive through the mountains,” notes Vice, who bring us the video above. Potentially explosive disputes naturally arise, and must be settled outside the law. Rather than rely on state intervention, residents wait to slug it out on Takanakuy. The name of the festival come from Quechua — the region’s indigenous language — and means “to hit each other” or, more idiomatically, “when the blood is boiling.” But combatants have had upwards of twelve months to cool before they step into a ring of cheering spectators and go hand-to-hand with an opponent. Fights are also officiated by referees, who do crowd control with short rope whips and call a fight as soon as someone goes down. Takanakuy is ritualized combat, not bloodsport. Although traditionally dominated by men, women, and children also participate in fights, which usually only last a couple minutes or so. “Some traditionalists disapprove of female participation in Takanakuy,” writes photojournalist Mike Kai Chen at The New York Times, but “an increasing number of women in Chumbivilcas are defying convention and stepping up to fight in front of their community.” Male fighters wear boots, flashy leather chaps, and elaborate, hand-sewn masks with taxidermied birds on top. Women wear elegant dresses with fine embroidery, and wrap their wrists in colorful embroidered cloth. “The ultimate aim is to begin the new year in peace. For this reason every fight… begins and ends with a hug”… or, at the very least, a handshake. The festival also involves much dancing, eating, drinking, craft sales, and Christmas celebrations. Suemedha Sood at BBC Travel compares Takanakuy to Seinfeld‘s “Festivus,” the alt-winter holiday for the airing of grievances and feats of strength. But it’s no joke. “The festival seeks to resolve conflict, strengthen community bonds and hopefully, arrive at a greater peace.” Libertarian economists Edwar Escalante and Raymond March frame Takanakuy as “a credible mechanism of law enforcement in an orderly fashion with social acceptance.” For indigenous teacher and author and participant Victor Laime Mantilla, it’s something more, part of “the fight to reclaim the rights of indigenous people.” “In the cities,” says Mantilla, “the Chumbivilcas are still seen as a savage culture.” But they have kept the peace amongst themselves with no need for Peruvian authorities, fusing an indigenous music called Huaylia with other traditions that date back even before the Incas. Takanakuy arose as a response to systems of colonial oppression. When “justice in Chumbivilcas was solely administered by powerful people,” Mantilla says, “people from the community always lost their case. What can I do with a justice like that? I’d rather have my own justice in public.” See the costumes of the traditional Takanakuy characters over at Vice and see Chen’s stunning photos of friendly fistfights and Takanakuy fun at The New York Times. Related Content: Peruvian Singer & Rapper, Renata Flores, Helps Preserve Quechua with Viral Hits on YouTube Speaking in Whistles: The Whistled Language of Oaxaca, Mexico Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Every Christmas, Peruvians Living in the Andes Settle Their Scores at Fist-Fighting Festivals is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | Hear Sherlock Holmes Stories Read by The Great Christopher Lee The extended Sherlock Holmes Universe, as we might call it, has grown so vast in the last century (as with other franchises that have universes) that it’s possible to call oneself a fan without ever having read the source material. Depending on one’s persuasion, this is either heresy or the inevitable outcome of so much mediation by Holmesian high priests, none of whom can resist writing Holmes fan fiction of their own. But Sherlockians agree: the true Holmes Canon (yes, it’s capitalized) consists of only 60 works — 56 short stories and four novels, excluding apocrypha. No more, no less. (And they’re in the public domain!) The Canon safeguards Arthur Conan Doyle’s work against the extra-voluminous flood of pastichists, parodists, and imposters appearing on the scene since Holmes’ first appearance in 1892. (Doyle personally liked Peter Pan author J.M. Barrie’s Holmes parody, “The Adventure of the Two Collaborators,” so much he included it in his autobiography.) The Holmes Canon remains untouchable for its wit, ingenuity, and the true strangeness of its detective — a portrait of perhaps the most emotionally avoidant protagonist in English literature when we first meet him:

How to make such a cold fish compelling? With a host of quirks, an ingenious mind, a “Bohemian soul,” some unsavory qualities, and at least one or two human attachments, if you can call them that. Sherlock’s cold, logical exterior masks considerable passion, inspiring fan theories about an ancestral relationship to Star Trek’s Spock. But of course, we see Holmes almost entirely through the eyes of his sidekick and amanuensis, James Watson, who has his biases. When Holmes stepped out of the stories and into radio and screen adaptations, he became his own man, so to speak — or a series of leading men: Basil Rathbone, John Gielgud, Ian McKellen, Michael Caine, Robert Downey, Jr., Benedict Cumberbatch, and the late Christopher Lee, who played not one of Doyle’s characters, but four, beginning with his role as Sir Henry Baskerville, with Peter Cushing as Holmes, in a 1959 adaptation. In 1962, Lee took on the role of Holmes himself in a German-Italian production, Sherlock Holmes and the Deadly Necklace, an original story based on Doyle’s work. He played Holmes’ smarter but unmotivated older brother, Mycroft, in 1970, then played a much older Holmes twice more in the 90s, pausing along the way for the role of Arnaud, a character in another Doyle adaptation, The Leather Funnel, in 1973 and the narrator of a 1985 Holmes documentary, The Many Faces of Sherlock Holmes. In an extraordinary career, Lee became an icon in the worlds of horror, science fiction, fantasy, and Sherlock Holmes, a genre all its own, into which he fit perfectly. In the videos here, you can hear Lee read four of the last twelve Holmes stories Doyle wrote in the final decade of his life. These were collected in 1927 in The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes. We begin, at the top, with the very last of the 56 canonical stories, “The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place.” Lee may never have played Dr. Watson, but we can imagine him bringing his familiar gravitas to that role, too, as he narrates in his deep mellifluous voice. Find links to 7 more stories from Doyle’s last collection, read by Lee, on Metafilter, and hear him narrate The Many Faces of Sherlock Holmes, just below. Related Content: Arthur Conan Doyle Names His 19 Favorite Sherlock Holmes Stories Horror Legend Christopher Lee Reads Bram Stoker’s Dracula Sherlock Holmes Is Now in the Public Domain, Declares US Judge Read the Lost Sherlock Holmes Story That Was Just Discovered in an Attic in Scotland Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Hear Sherlock Holmes Stories Read by The Great Christopher Lee is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

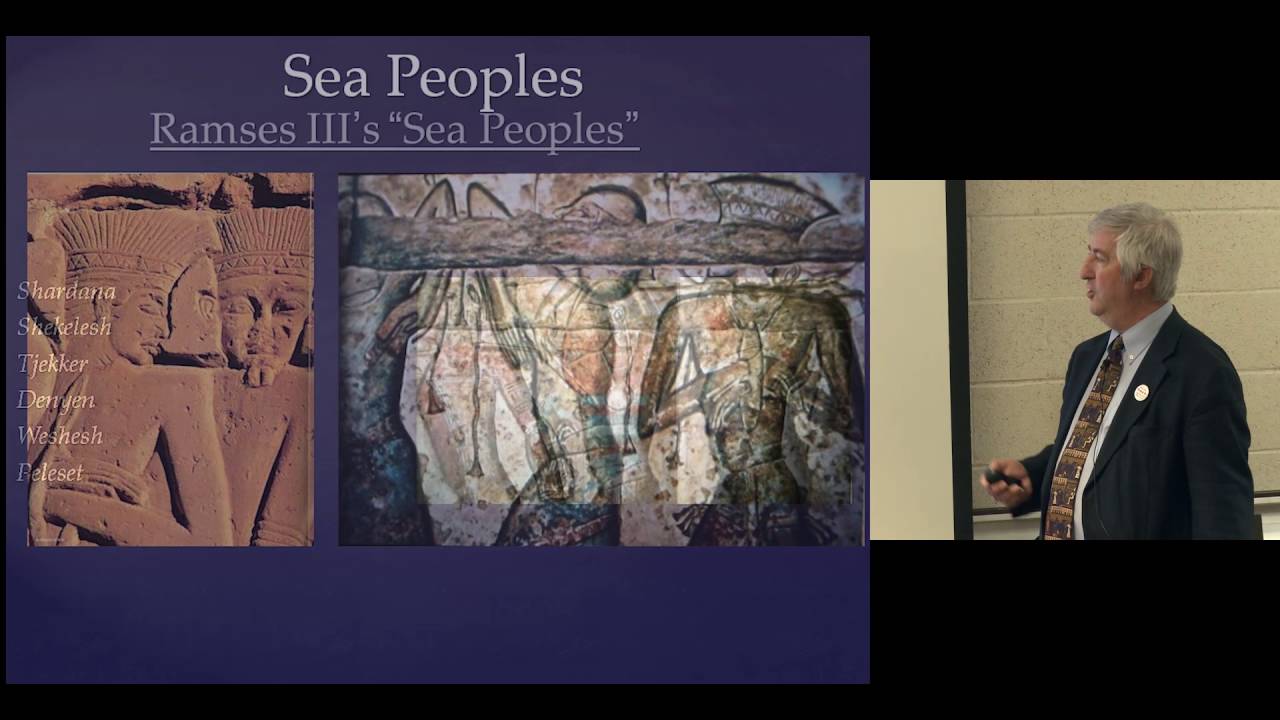

| 7:00p | Why Civilization Collapsed in 1177 BC: Watch Classicist Eric Cline’s Lecture That Has Already Garnered 5.5 Million Views Eric Cline is a man of the Bronze Age. “If I could be reincarnated backwards,” he says in the lecture above, “I would choose to live back then. I’m sure I would not live more than about 48 hours, but it’d be a good 48 hours.” He may give himself too little credit: as he goes on to demonstrate in the hour that follows, he has as thorough an all-around knowledge of life in the Bronze Age as anyone alive in the 21st century. But of course, his prospects for survival in that era — or indeed anyone’s — depend on which part of it we’re talking about. The Bronze Age lasted a long time, from roughly 3300 to 1200 BC — at the end of which, ancient-history specialists agree, civilization collapsed. What the specialists don’t quite agree on is how it happened. Cline makes his own case in the book 1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed. The title, which seems to have been the result of the publishing industry’s invincible enthusiasm for naming books after years, may soon need an update: as Cline admits, it reflects a convention among scholars about how to label the titular event that has just been revised, and has since been revised back. And in any case, the collapse of civilization among the distinct but interconnected Egyptians, Hittites, Canaanites, Cypriots, Minoans, Mycenaeans, Assyrians, and Babylonians of the Bronze Age took not a year, he explains, but more like a century. This complicated process has no one explanation — and more to the point, no one cause. Many flourishing cities of Bronze Age civilization were indeed destroyed by 1177 BC or soon thereafter. The “old, simple explanation” for this was that “a drought caused famine, which eventually caused the Sea Peoples to start moving and creating havoc, which caused the collapse.” Cline opts to include these factors and others, including earthquakes and rebellions, whose effects spread to afflict all parts of this early “globalized” part of the world. The result was a “systems collapse,” involving the breakdown of “central administrative organization,” the “disappearance of the traditional elite class,” the “collapse of the centralized economy,” as well as “settlement shifts and population decline.” Systems collapses have also happened in other places and at other times. Given the enormous intensification of globalization since the Bronze Age and the continued threats issued by the natural world, could another happen here and now? Pointing to the climate change, famines and droughts, earthquakes, rebellions, acts of bellicosity, and economic troubles in evidence today, Cline adds that “the only thing missing are the Sea Peoples” — and even then suggests that ISIS and refugees from Syria could be playing a similarly disruptive role. Given that this talk has racked up more than five and a half million views so far, it seems he makes a convincing case, though the appeal could owe as much to his jokes. Not all of us, he acknowledges, will accept the relevance of the subject: “It’s history,” as we reassure ourselves. “It never repeats itself.” Related Content: The History of Civilization Mapped in 13 Minutes: 5000 BC to 2014 AD Get the History of the World in 46 Lectures: A Free Online Course from Columbia University M.I.T. Computer Program Alarmingly Predicts in 1973 That Civilization Will End by 2040 Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Why Civilization Collapsed in 1177 BC: Watch Classicist Eric Cline’s Lecture That Has Already Garnered 5.5 Million Views is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/08/12 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |