[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, August 19th, 2021

| Time | Event |

| 3:08a | Watch The Weight of the Nation Free Online: An Emmy-Nominated HBO Documentary Films Series on Obesity The Emmy-nominated HBO Documentary Films series on obesity, The Weight of the Nation, premiered in May 2012. And it’s now free to watch online. Made in collaboration with the NIH, the four-part series — Consequences, Choices, Children in Crisis, and Challenges —explored America’s obesity epidemic–its causes, symptoms, treatments, and solutions. You can watch all four parts above and below. The documentary will be added to our list of Free Documentaries, a subset of our collection, 1,150 Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, etc.. Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Watch The Weight of the Nation Free Online: An Emmy-Nominated HBO Documentary Films Series on Obesity is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00a | Make Body Language Your Superpower: A 15-Minute Primer on Body Language & Public Speaking from Stanford Business School A few years ago, the idea of “power poses” — that is, physical stances that increase the dynamism of one’s personality — gained a great many adherents in a very short time, but not long thereafter emerged doubts as to its scientific soundness. Nevertheless, while standing with your hands on your hips may not change who you are, we can fairly claim that such a thing as body language does exist. And in that language, certain bodily arrangements communicate better messages than others: according to the presenters of the talk above, keeping your hands power-poseishly on your hips is actually a textbook bad public-speaking position, down there with shoving them in your pockets or clasping them before you in the dreaded “fig leaf.” Now viewed well over 5.5 million times, “Make Body Language Your Superpower” was originally delivered as the final project of a team of graduate students at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business. That same institution gave us lecturer Matt Abrahams’ talk “Think Fast, Talk Smart,” which, with its 23 million views and counting, suggests its campus possesses a literal fount of public-speaking wisdom. Working as a team, these students keep it short and simple, accompanying their talk with takeaway-announcing Powerpoint slides (“1. Posture breeds success, 2. Gestures strengthen our message, 3. The audience’s body matters too”) and even a video clip that vividly illustrates what not to do: in this case, with a fidgety, rotation-heavy turn on stage by Armageddon and Transformers auteur Michael Bay. Though we can’t hear what Bay is saying, we couldn’t be blamed for assuming it’s not the truth. That owes not so much to the Hollywood penchant for dissimulation and hyperbole as it does to his particular stances, gestures, and perambulations, all of a kind that primes our subconsciousness to expect lies. “We all want to avoid our own Michael Bay moments when we communicate,” says one of the presenters, but even when we take pains to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, the defensive postures into which many of us instinctively retreat can undercut our efforts. “Decoding Deceptive Body Language,” the talk just above, can help us learn both to identify the impression of dishonesty and to avoid giving it ourselves. Not that it’s always easy: as the example of Bill Clinton underscores in both these presentations, even master communicators have their slip-ups. Related Content: How to Spot Bullshit: A Primer by Princeton Philosopher Harry Frankfurt How to Sound Smart in a TED Talk: A Funny Primer by Saturday Night Live‘s Will Stephen Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Make Body Language Your Superpower: A 15-Minute Primer on Body Language & Public Speaking from Stanford Business School is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

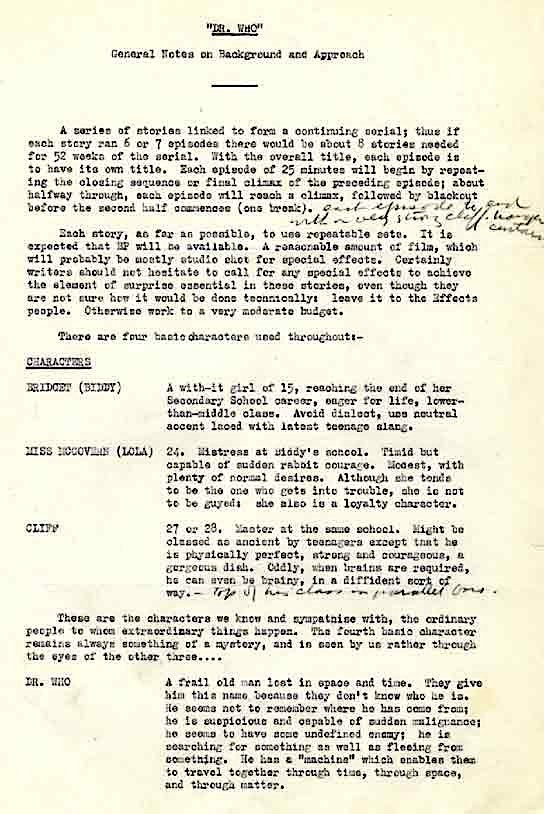

| 11:00a | How Doctor Who First Started as a Family Educational TV Program (1963) Those who grew up with the BBC sci-fi series Doctor Who watched from “behind the sofa,” a popular phrase associated with the show for the rubbery, bug-eyed monsters it held in store each week for loyal viewers. Although it may be hard for those who didn’t experience it in their formative years to understand, Doctor Who has frequently been voted the scariest TV show of all time, over grislier, big-budget series like The Walking Dead, and has done so without losing its sense of humor, a testament to the conceit of “regeneration” keeping things fresh by updating the Doctor and his companions every few years. Space monsters, Daleks, Cybermen, and a revolving cast, however, were not part of Doctor Who’s original remit. The show began as an educational program on the BBC, and this explains many of its integral parts, which have remained throughout its first run from 1963 to 1989 and its revival from 2005 to the present. These elements include the TARDIS, companions of various ages, the Coal Hill School, and the Doctor himself, a Time Lord from the planet Gallifrey with interstellar technology and a dodgy memory. We find the core premise in the show’s pilot episode and original 4-part series, An Unearthly Child, which introduced William Hartnell as the Doctor, Carole Ann Ford as his granddaughter, Susan Foreman (originally named Barbara, or “Biddy”), and Jaqueline Hill and William Russell as school teachers Barbara Wright and Ian Chesterton. BBC drama head Sydney Newman had tasked writers with creating a family educational show to meet the network’s public service mandate, and came up with the idea of a science fiction show as a way to have characters visit historical periods and talk about science in an entertaining way. “Doctor Who’s early historical stories emphasize education by downplaying the programme’s fantasy with minimal science-fiction elements,” writes Tom Steward at Deletion. The idea of a time machine bigger on the inside than the outside came from Newman. Writer Anthony Coburn turned it into a police box after a note from Newman asking for a “tangible” symbol. Newman “instructed writers to ‘get across the basis of teaching of educational experience.'” When they came back with a story about Daleks, he balked: “No bug-eyed monsters,” he wrote, no alien baddies, no actors in rubber suits. This was to be a serious show about serious educational subjects. Script changes and technical challenges meant months of setback and delays. It was difficult for some critics to take the resulting four episode arc particularly seriously. The first episode showed Barbara and Ian discovering the TARDIS in a London junkyard. Then they are all transported to the prehistoric past, where they observe (and escape) a power struggle among prehistoric cave people. (Guardian critic Mary Crozier lamented that the “wigs and furry pelts and clubs were all ludicrous.”) The show’s debut was also inauspicious: November 23, 1963, the day after John F. Kennedy’s assassination. The BBC reran the first episode the next week and picked up another 2 million viewers. Still, it had become clear after the first series that in order to survive, Doctor Who would have “to give the public what they wanted,” Steward writes, “rather than what was good for them.” Thus, the Daleks debuted in the second season, and by the mid-60s, historical stories were replaced with “fantasies in historical costume featuring anachronistic villains or monsters.” The show became a weekly creature feature and introduced terrifying villains like Davros, the Daleks’ creator, a cross between a Strangelove-like Nazi scientist and Star Wars’ clone-happy Emperor Palpatine (Davros came first). The costumes may look silly in hindsight, but as childhood Who fan Charlie Jane Anders writes at io9, “those of us who are adults now didn’t have huge screen HD televisions when we were kids.” (And those of us who remember it, remember being terrified by equally goofy costuming in The Land of the Lost.) Look past the low-budget effects and Doctor Who becomes pure horror, exploring very dark territory with only a sonic screwdriver, a few friends, and a quirky sense of humor — or 13 quirky senses of humor, including Jodie Whittaker’s as the current Doctor and first woman to fill the role. As you can see from the clips of the first episode above, Doctor Who established its weird air of existential dread from the start with Delia Derbyshire’s otherworldly theme and some avant-garde camera effects in lieu of bigger-budget spectacles. The show did not retain much from its educational beginnings aside from the key characters and the look and feel of the TARDIS. It was “seen to have failed as pedagogy,” writes Steward, but as a body of science fiction lore that continues to stay relevant, it has all sorts of lessons to teach about courage, companionship, and the value of the right tool for the right job.

Related Content: 30 Hours of Doctor Who Audio Dramas Now Free to Stream Online The Fascinating Story of How Delia Derbyshire Created the Original Doctor Who Theme A Detailed, Track-by-Track Analysis of the Doctor Who Theme Music Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness How Doctor Who First Started as a Family Educational TV Program (1963) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | Songs That Use “Word Painting”: The Art of Creating Music That Sounds Like the Lyrics “There’s no love song finer, but how strange the change from major to minor, everytime we say goodbye.” In the line above from Cole Porter’s “Every Time We Say Goodbye,” we’re moved from the happiness of love to the sadness of parting, and so too do the chords change, from major to minor, thus subtly changing the mood of the song. The technique is a clever example of a songwriting method called “word painting,” or prosody, when lyrics are accompanied by a rhythmic, melodic, or harmonic shift that complements their meaning. We hear it in pop music all the time, drawing our attention to significant moments, and shaping the emotional impact of words and phrases. The word “Stop,” for example, appears over and over in pop music, as the video above from David Bennett shows, accompanied by a full stop from the band. Spanish-language hit “Despacito” (which means “slowly”) slows the down tempo while the titular word is sung. There are innumerable examples of melodies rising and falling to lyrics like “high, up, down” and “low.” A more sophisticated example of word paining comes from Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” which tells us exactly what the music’s doing — “It goes like this, the fourth, the fifth, the minor fall, the major lift.” As ingenious as these moves are, Bennett goes on to show us how word painting can be “even more nuanced” in classics like The Doors’ “Riders on the Storm.” As Ray Manzarek himself explains in an interview clip, his keyboard part led to an onomatopoeia effect: lyrics, melody, and sound effects all coming together to express the entire theme. Bennett shows in his second word painting video, above, how studio effects can also be used to sync music and lyrics, such as the murky eq effect applied to Billie Eilish’s voice on the word “underwater” in her song “Everything I Wanted.” Examples of effects like this date back at least to Jimi Hendrix, who pioneered the studio as a songwriting tool, but word painting as a songwriting method requires no special technology. The Jackson Five’s “ABC,” for instance, lands on E? and C during the line “I before E except after C,” and the famous chorus is sung to the notes A?, B?m7, and C. Here, the notes themselves tell the story, simple but undoubtedly effective. All of the examples Bennett adduces may come from popular music, but word painting is as old as poetry, which was once inseparable from song. For as long as humans have communicated with literary epics, funeral rites, tragedies, comedies, and love songs, we have used prosody to shape words with music, and music according to the meaning of our words. Related Content: Tom Petty Takes You Inside His Songwriting Craft How David Bowie Used William S. Burroughs’ Cut-Up Method to Write His Unforgettable Lyrics Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Songs That Use “Word Painting”: The Art of Creating Music That Sounds Like the Lyrics is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/08/19 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |