[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, August 26th, 2021

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | The Life & Music of the Godmother of Rock and Roll, Sister Rosetta Tharpe When I was a wee lad I was interested in the history of rock and roll. Where did it come from? Who started it? But also when I was wee, there didn’t seem to be a lot of information around, certainly not in my library downtown. But when Muddy Waters died in 1983, I started to understand that rock and roll was sped-up blues, and pieces started to slot together. However, women weren’t part of the equation. (Blame Rolling Stone Magazine). That’s a long way of saying the Sister Rosetta Tharpe should be better known than she is, especially as one dubbed the Godmother of Rock and Roll. Playing scratchy, distorted electric guitar and singing as if on a direct line to heaven, Tharpe would go on to influence everybody from Elvis Presley to Chuck Berry, and everybody who came after her. So why is she not more of a household name? The 2011 BBC documentary above (split into four 15-minute chunks) resuscitates a legend who not only played a mean guitar but set the standard for the gospel-crossover artist, making a name on the gospel circuit, but making her fame in the secular nightclubs of America. Tharpe’s distinction is that she returned to gospel without losing any of her edge. A precocious youngster in Arkansas during the early 1920s, she became the star of her Pentecostal church starting at four years old. Raised by her mother, then forced into an arranged marriage at 19-years-old to an older preacher, Thomas Tharpe, she kept his name when she left their abusive marriage. She and her mother relocated to Chicago, where blues and jazz were intermingling in a hothouse culture. Decca signed her, and although she told her churchgoing friends that she had to sing these secular songs because of that darned seven-year contract, Tharpe rose to fame quickly. The footage of her singing in front of the Cotton Club band led by Lucky Millinder is one of a cheeky, charming 23 year old. As the doc makes clear, Tharpe had a rebellious streak, didn’t do what she was told, and pushed boundaries in a very segregated America. She invited the all-white Jordanaires to tour with her, surprising house managers and booking agents alike. And she carried on a love affair and creative partnership with fellow gospel singer Marie Knight for decades, very much on the down low. So perhaps this is the reason Tharpe has not been on our collective radar—we’ve been slow to admit that rock guitar was created by a queer black woman devoted to the Lord. Nobody in the audience knew this, though, at the abandoned railway station at Wilbraham Road, Manchester, in May 1964. On one side of the station’s tracks, British teenagers were gathered to hear raw, rock and roll from America. On the other side, Tharpe stands with her guitar, wearing a thick coat to protect her from the spring rain. Backed by her band, she channels a holy force and sings about the rain of the Great Flood, the lyrics abstract and repetitive, as if in a trance. The footage opens the documentary and makes as good a case as any of why Tharpe should be part of the pantheon of rock royalty. (You can see the whole clip here.) Back in the States, Tharpe had been eclipsed by Mahalia Jackson, but the Brits didn’t know any of that. They just sense they’ve tapped into one of the sources for the music exploding around them. It took until 2018 for Tharpe to be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, years after all those white boy copycats. Now is the time to re-discover her and hear what you’ve been missing. Related Content: New Web Project Immortalizes the Overlooked Women Who Helped Create Rock and Roll in the 1950s An Introduction to Sister Rosetta Tharpe Muddy Waters and Friends on the Blues and Gospel Train, 1964 Watch the Hot Guitar Solos of Sister Rosetta Tharpe Revisit The Life & Music of Sister Rosetta Tharpe: ‘The Godmother of Rock and Roll’ The Women of Rock: Discover an Oral History Project That Features Pioneering Women in Rock Music Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here. The Life & Music of the Godmother of Rock and Roll, Sister Rosetta Tharpe is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

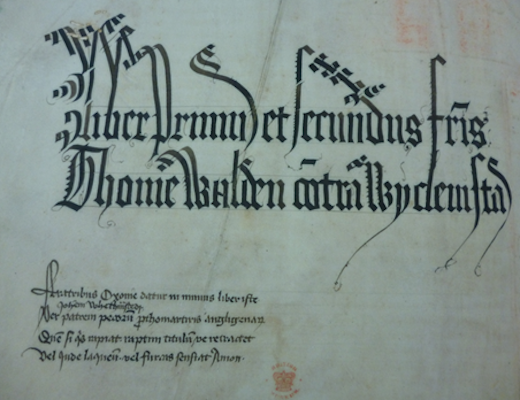

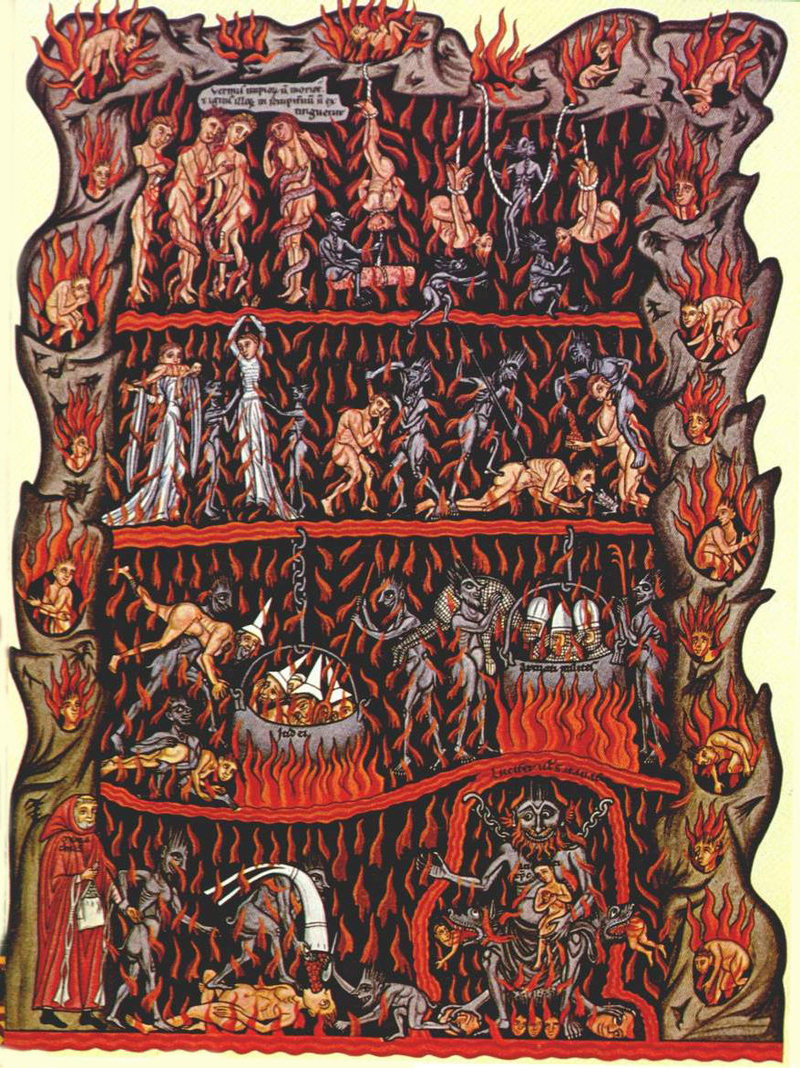

| 11:00a | Medieval Scribes Discouraged Theft of Manuscripts by Adding Curses Threatening Death & Damnation to Their Pages

I’ve concluded that one shouldn’t lend a book unless one is prepared to part with it for good. But most books are fairly easy to replace. Not so in the Middle Ages, when every manuscript counted as one of a kind. Theft was often on the minds of the scribes who copied and illustrated books, a laborious task requiring literal hours of blood, sweat and tears each day. Scribal copying took place “only by natural light — candles were too big a risk to the books,” Sarah Laskow writes at Atlas Obscura. Bent over double, scribes could not let their attention wander. The art, one scribe complained, “extinguishes the light from the eyes, it bends the back, it crushes the viscera and the ribs, it brings forth pain to the kidneys, and weariness to the whole body.” The results deserved high security, and Medieval monks “did not hesitate to use the worst punishments they knew” for manuscript theft, writes Laskow, namely threats of “excommunication from the church and horrible, painful death.”

Theft deterrence came in the form of ingenious curses, written into the manuscripts themselves, going “back to the 7th century BCE,” Rebecca Romney writes at Mental Floss. Appearing “in Latin, vernacular European languages, Arabic, Greek, and more,” they came in such creative flavors as death by roasting, as in a Bible copied in Germany around 1172: “If anyone steals it: may he die, may he be roasted in a frying pan, may the falling sickness [epilepsy] and fever attack him, and may he be rotated [on the breaking wheel] and hanged. Amen.” A few hundred years later, a manuscript curse from 15th-century France also promises roasting, or worse:

The plucking out of eyes also appears to have been a theme. “Whoever to steal this volume tries, Out with his eyes, out with his eyes!” warns the final couplet in a 13th-century curse from a Vatican Library manuscript. Another curse in verse, found by author Marc Drogin, author of Anathema! Medieval Scribes and the History of Book Curses, gets especially graphic with the eye gouging:

The hoped-for consequences were not always so grimly humorous. “Gruesome as these punishments seem,” the British Library writes, “to most medieval readers the worst curses were those that put the eternal fate of their souls at risk rather than their bodily health.” These would often be marked with the Greek word “Anathema,” sometimes “followed by the Aramaic formula ‘Maranatha’ (‘Come, Lord!’).” Both appear in a curse added to a manuscript of letters and sermons from Lesnes Abbey. Yet, unlike most medieval curses, here the thief is given a chance to make restitution. “Anyone who removes it or does damage to it: if the same person does not repay the church sufficiently, may he be cursed.”

Curses were not the only security solutions of manuscript culture. Medieval monks also used book chains and locked chests to secure the fruit of their hard labor. As the old saying goes, “trust in God, but tie your camel.” But if locks and divine providence should fail, scribes trusted that the fear of punishment – even eternal damnation — down the road would be enough to make would-be book thieves think again. Related Content: 160,000+ Medieval Manuscripts Online: Where to Find Them The Illuminated Manuscripts of Medieval Europe: A Free Online Course from the University of Colorado Why Butt Trumpets & Other Bizarre Images Appeared in Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Medieval Scribes Discouraged Theft of Manuscripts by Adding Curses Threatening Death & Damnation to Their Pages is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | Benedict Cumberbatch Reads “the Best Cover Letter Ever Written” In the 1930s, many a writer journeyed to Hollywood in order to make his fortune. The screenwriter’s life didn’t sit well with some of them — just ask F. Scott Fitzgerald or William Faulkner — but a fair few made more than a go of it out West. Take the Baltimore-born Robert Pirosh, whose studies at the Sorbonne and the University of Berlin landed him a job as a copywriter in New York. This work seems to have proven less than satisfactory, as evidenced by the piece of correspondence that, still in his early twenties, he wrote and sent to “as many directors, producers and studio executives as he could find.” It wasn’t just a request for work; it was what Letters Live today calls “the best cover letter ever written.” Pirosh’s impressive missive, which you can hear read aloud by favorite Letters Live performer Benedict Cumberbatch in the video above, runs, in full, as follows:

Though not known as an unsubtle actor, Cumberbatch seizes the opportunity to deliver each and every one of these choice words with its own variety of exaggerated relish. Though none of these terms is especially recherché on its own, they must collectively have given the impression of a formidable mastery of the English language, especially to the ear of the average Hollywood big-shot. One way or another, Pirosh’s letter did the trick: according to Letters of Note, it “secured him three interviews, one of which led to his job as a junior writer at MGM. Fifteen years later,” he “won an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for his work on the war film Battleground.” A World War II picture, Battleground was written at least in part from Pirosh’s own experience: a few years into his Hollywood career, he enlisted and made a return to Europe, this time as a Master Sergeant in the 320th Regiment, 35th Infantry Division, seeing action in France and Germany. After the war he went right back to writing and producing, remaining active in the entertainment industry until at least the 1970s (and in fact, his writing credits include contributions to such programs that defined that decade as Mannix, Barnaby Jones, and Hawaii Five-O). Pirosh’s was an enviable 20th-century career, and one that began with a suitably brazen — and still convincing — 20th-century advertisement for himself. Related Content: Hunter S. Thompson’s Ballsy Job Application Letter (1958) Benedict Cumberbatch Reads Kurt Vonnegut’s Letter of Advice to People Living in the Year 2088 Benedict Cumberbatch Reads Albert Camus’ Touching Thank You Letter to His Elementary School Teacher Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Benedict Cumberbatch Reads “the Best Cover Letter Ever Written” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/08/26 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |