[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, August 31st, 2021

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | Watch Lost Studio Footage of Brian Wilson Conducting “Good Vibrations,” The Beach Boys’ Brilliant “Pocket Symphony” After Brian Wilson created what Hendrix called the “psychedelic barbershop quartet” sound of the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, he moved on to what he promised would be another quantum leap beyond. “Our new album,” Smile, he claimed, “will be as much an improvement over Sounds as that was over Summer Days.” But in his pursuit to almost single-handedly surpass the Beatles in the art of studio perfectionism, Wilson overreached. He famously scrapped the Smile sessions, and instead released the hastily-recorded Smiley Smile to fulfill contract obligations in 1967. Smiley Smile’s peculiar genius went unrecognized at the time, particularly because its centerpiece, “Good Vibrations,” had set expectations so high. Recorded and released as a single in 1966, the song would be referred to as a “pocket symphony” (a phrase invented either by Wilson himself or publicist Derek Taylor). Even the jaded session players who sat in for the hours of recording — veterans from the famed “Wrecking Crew” — knew they were making something that transcended the usual rut of pop simplicity. “We were doing two, three record dates a day,” says organ player Mike Melvoin, “and the level of sophistication was, like, not really sophisticated at all.” The “Good Vibrations” sessions were another experience entirely. “All of a sudden, you walk in, and here’s run-on songs. It’s like this section followed by that section followed by this section, and each of them with a completely different character. And you’re going, ‘Whoa.’” Wrecking Crew bassist Carol Kay, who sat in for the sessions but didn’t make the final mix, remembers thinking, “that wasn’t your normal rock ‘n’ roll…. You were part of a symphony.” Wilson’s pop symphonies were created and arranged not on paper but during the recording sessions themselves, which accounted for the 90 hours of tape and tens of thousands of dollars in expenses, the most money ever spent on a pop single. He made creative decisions according to what he called “feels,” fragments of melody and sound that formed his avant-garde pastiches. “Each feel represented a mood or an emotion I’d felt,” he recalled, “and I planned to fit them together like a mosaic.” Not everyone could see the plan at first. But when Wilson finally emerged from months of isolation after cutting and mixing hours and hours of tape, the rest of the band was “very blown out,” he says. “They were most blown out. They said, ‘Goddamn, how can you possibly do this, Brian?’ I said, ‘Something got inside of me.’… They go, ‘Well, it’s fantastic.’ And so they sang really good just to show me how much they liked it.” In the edited footage at the top, taken over the six months of recording in four different studios, you can see drummer Hal Blaine, organ player Mick Melvoin, double bass player Lyle Ritz, and the Beach Boys themselves all recording their parts. To the press, Wilson told one story — “Good Vibrations” was “still sticking pretty close to that same boy-girl thing, you know, but with a difference. And it’s a start, it’s definitely a start.” But the song — which he first wanted to call “Good Vibes” — is very much meant to suggest “the healthy emanations that should result from psychic tranquility and inner peace,” wrote Bruce Golden in The Beach Boys: Southern California Pastoral. In that sense, “Good Vibrations” was aspirational, almost tragically so, for Wilson, who could not fulfill its promises. Yet, in another sense, “Good Vibrations” is itself the fulfillment of Wilson’s creative promise, an eternally brilliant “pocket symphony” — and as Wilson told engineer Chuck Britz during the sessions, his “whole life performance in one track.” Related Content: How the Beach Boys Created Their Pop Masterpieces: “Good Vibrations,” Pet Sounds, and More Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Watch Lost Studio Footage of Brian Wilson Conducting “Good Vibrations,” The Beach Boys’ Brilliant “Pocket Symphony” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | Build Wooden Models of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Great Building: The Guggenheim, Unity Temple, Johnson Wax Headquarters & More

Frank Lloyd Wright had his eccentricities, in not just his personal and professional conduct but also the very language with which he described the world. Among the enduringly fascinating elements of his idiolect is the word Usonian, which refers to things of or pertaining to the United States of America. Wright didn’t coin the term: its earliest recorded user is the early 20th-century writer James Duff Law, who declared that “We of the United States, in justice to Canadians and Mexicans, have no right to use the title ‘Americans’ when referring to matters pertaining exclusively to ourselves.” The most famous architect in American history took Usonian further, using it to label an American architectural sensibility — of, naturally, his own design.

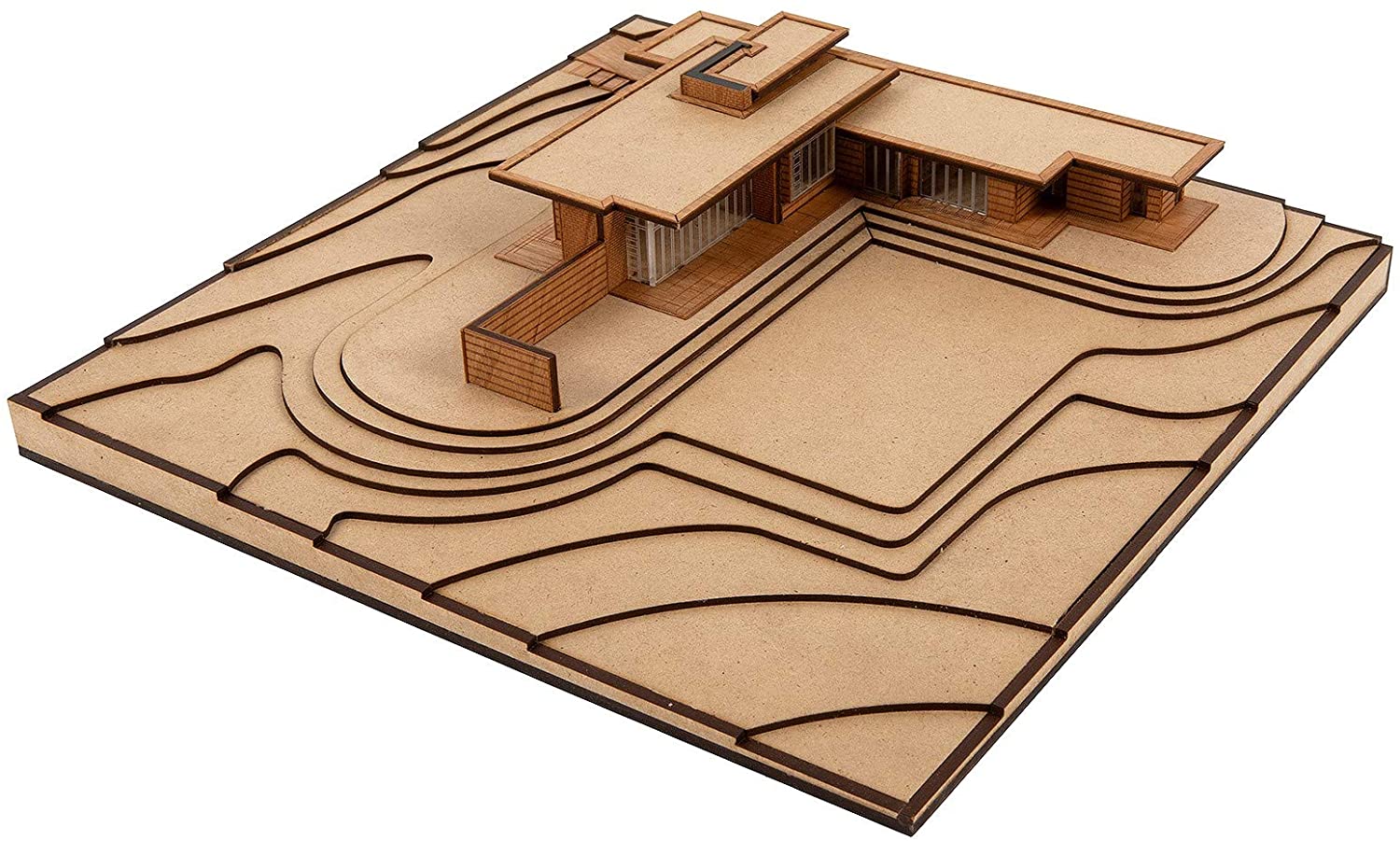

Though Wright did envision an ideally Usonian city, his clearest expressions of the aesthetic stand today in the form of the Usonian houses. Built between 1934 and 1958, these sixty or so residences take advantage, as Wright saw it, of the range of distinctive settings offered up by the landscapes of the United States. Designed with features like garden terraces, clerestory windows, flat roofs with wide overhangs, and easy visual and physical passage between the indoors and outdoors, these urban-rural hybrids still today draw the admiration of architects and non-architects alike. But truly to understand a Usonian house, perhaps you must build one yourself: luckily, the Little Building Company offers a model kit that lets you do just that.

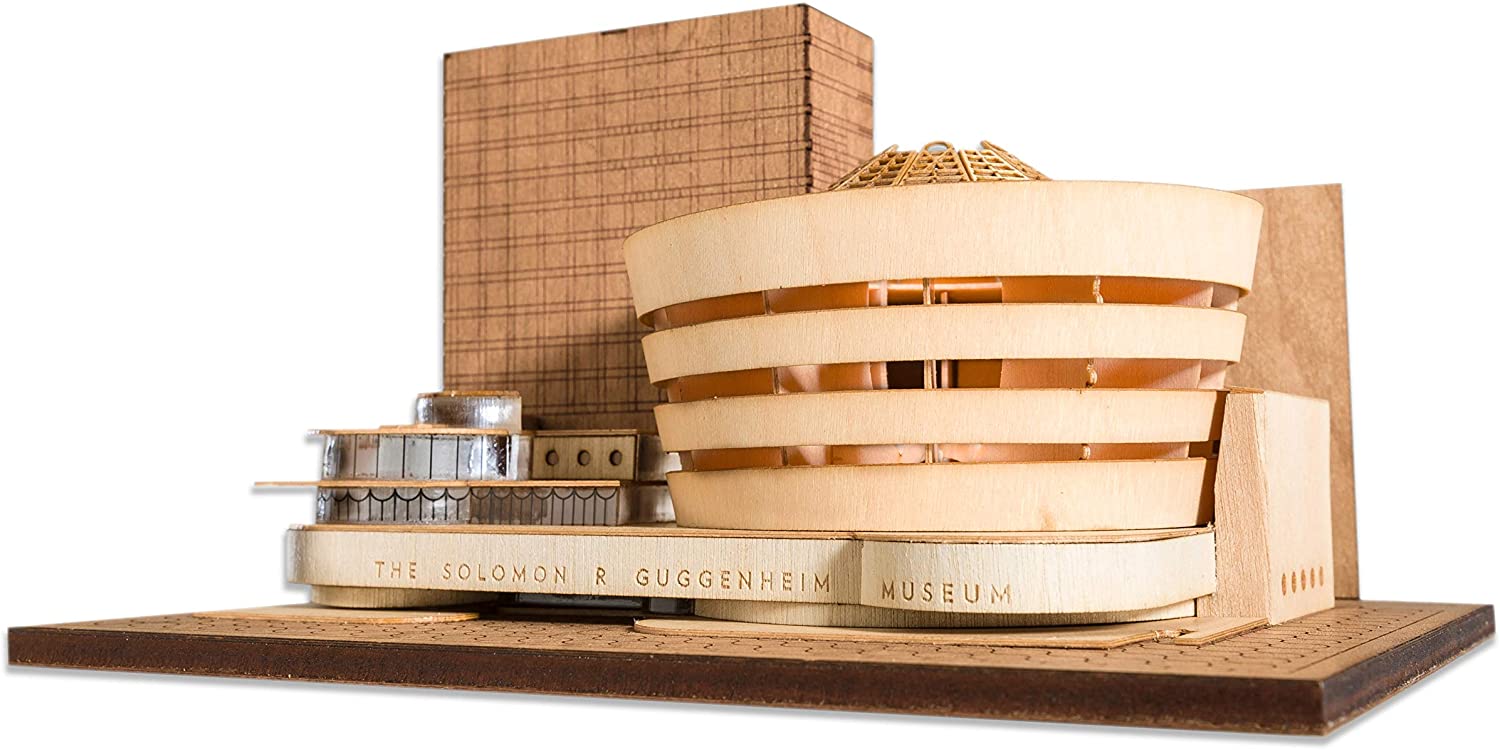

Their Wright lineup also includes miniature wooden versions of his 1908 Unity Temple in Oak Park, his 1937 Johnson Wax Headquarters in Racine, and his 1937 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. The differences in scale and complexity between these buildings make for a natural model-building difficulty curve: once you’ve done a Wright house, you’ll be ready for a Wright temple; once you’ve done a Wright temple, you’ll be ready for a Wright corporate headquarters, and so on. Not only will the effort hone your manual dexterity, it will heighten your appreciation for the American architecture-defining innovations Wright pulled off in the early 20th century. But do you have to be from the United States to understand the Usonian? Based in Australia and selling to the world, the Little Building Company suggests not. Related Content: Frank Lloyd Wright Designs an Urban Utopia: See His Hand-Drawn Sketches of Broadacre City (1932) The Modernist Gas Stations of Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe How Frank Lloyd Wright’s Son Invented Lincoln Logs, “America’s National Toy” (1916) That Far Corner: Frank Lloyd Wright in Los Angeles – a Free Online Documentary Omoshiroi Blocks: Japanese Memo Pads Reveal Intricate Buildings As The Pages Get Used Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Build Wooden Models of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Great Building: The Guggenheim, Unity Temple, Johnson Wax Headquarters & More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | An Archaeologist Creates the Definitive Guide to Beer Cans

As a beverage of choice and necessity for much of the population in parts of the ancient world, beer has played an important role in archaeology. Beer cans, on the other hand, have not. Unlike millennia-old recipes, beer cans seem like no more than trash, even in a field where trash is highly treasured. This is a mistake, says archeologist Jane Busch. “The historical archaeologist who ignores the beer can at his site is like the prehistoric archeologist who ignores historic pottery.” David Maxwell, an expert in animal bones who trained as a Mayanist, has recognized the truth of this statement by turning his passion for beer can collecting into beer can archaeology, a tiny niche within the smaller field of “tin can archaeology.” Maxwell became the reigning expert on beer can dating when “in 1993, he published a field-identification guide in Historical Archaeology,” notes Jessica Gingrich at Atlas Obscura, “which has since become an industry standard and his most-read work.” The first commercial canned beer appeared in 1935, after several unsuccessful experiments starting in 1909. Experiments in beer canning took a hiatus during Prohibition, and canned beer itself went off the market during WWII as supplies of tin plate were rerouted to the war effort. During that interregnum, only the military shipped canned beer, to soldiers overseas in olive and camo-colored cans. When sales resumed after the war, beer cans assumed more routinized design elements. Maxwell himself became fascinated with beer cans from afar. “While canned beer sales exploded in the United States after World War II, Gingrich writes, “the industry failed to take off in Canada until the 1980s.” As a child in Canada, Maxwell collected bottle caps. “All the beer came in the same shape bottle,” he says. Cans seemed exotic, especially those of an older vintage. “They had punches to open them instead of pull rings, and all I knew was that they predated me.” The value of disposable artifacts less than 100 years old isn’t immediately apparent to most people, says Jim Rock, a pioneer of tin can studies who calls cans “the Rodney Dangerfield of archeology. They just don’t get any respect.” But the fact is “all archeology is garbage,” says Maxwell. Dating cans gives archeologists a picture of modern consumption patterns — and patterns of ecological destruction — in the refuse tossed on highways and the strata of trash found in construction sites, landfills, and even ancient dig sites, where dating beer cans can tell archeologists when earlier trespassers might have arrived, removed or altered artifacts, and left their trash behind. Maxwell, who has recently downsized his collection from 4500 to 1700 cans to save space, admits that a narrow focus on the beer can takes a special combination of skills. “Collectors are a fabulous resource for academics,” he says. “These are the guys who do the grunt work” — the endlessly curious citizen scientists of archaeology. “I can’t think of anyone else who would do that except someone who is obsessive about what it is that they are collecting.” In Maxwell, the obsessive collector and rigorous academic just happened to come together to produce the definitive guide. (See Beer Cans: A Guide for the Archaeologist online.) But even he has had to “face the question of what deserves to be archived and kept,” Nicola Jones writes at Sapiens. In discarding 3,000 of his own cans, most of them acquired through collectors online, he had to admit that “though the rusty cans were a part of history, they weren’t worth much to the rest of the world.” Related Content: Beer Archaeology: Yes, It’s a Thing The First Known Photograph of People Sharing a Beer (1843) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness An Archaeologist Creates the Definitive Guide to Beer Cans is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/08/31 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |