[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, September 2nd, 2021

- “Just Making Things and Being Alive About It: The Queer Games Scene” (2013) by Brendan Keogh

- “The 15 Queerest Video Games, Ranked” by Alley Hector (2018)

- “How Video Games Can Help LGBTQ+ Players Feel Like Themselves” by Laken Brooks

- “Press A, Be Gay: LGBTQ Representation in Video Games” by Jason Villemiz

- “15 Games With Non-Binary Friendly Character Creation” by Allison Stalberg

- “Can We Do Better Than Zelda? Queer Tropes in Video Games” a video from Feminist Frequency

- “The trans narrative in ‘The Last of Us Part II’ is compelling. There’s so much more to be done.” by Julie Muncy

- “‘Am I Trans?’: One Teen’s Quest and How Gaming Helped” (2015) from Note to Self podcast (which features Naomi)

- There are several specifically gay video game podcasts worth checking out, including Gay for Play and The Gayming Podcast.

| Time | Event |

| 7:01a | What Is “Queering” in Video Game Design? Naomi Clark on Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #103

While LGBTQ+ representation in video games has been improving (as with other media), Naomi Clark (who designed games for LEGO, Gamelab, Fresh Planet, Rebel Monkey, et al) has something more disruptive in mind when arguing for game “queerification.” The prototypical video game includes a more-or-less linear progression through a pre-defined story to a defined win condition, and anything that challenges that tradition to allow more self-expression is a step in the direction of queering. Many popular games now include a sandbox aspect that allows players to make their own decisions, and this gestures at a continuum of freedom in player-game relations, with the extreme being a game that just provides a platform for players to create their own games. Your host Mark Linsenmayer and guest co-host Tyler Hislop engage Naomi about topics like how games train us, character creation, glitches, speed runs, gamifying tasks, and economic and industry pressures in game design. Some games we touch on include The Sims, The Last of Us, Cyberpunk, and Mass Effect. Read Naomi’s presentation on “Queering Human-Game Relations.” Get involved with the NYU Gamecenter where Naomi works. You can also play her early game Sissyfight 2000 free online. A couple of her other creations that come up in our discussion include Wonder City and the card game Consentacle. Read her wisdom on Quora and follow her on Twitter @metasynthie. Some sources reviewed to prepare for this episode include: This episode includes bonus discussion you can access by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts. What Is “Queering” in Video Game Design? Naomi Clark on Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #103 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00a | The Evolutionary History of Fat: Biologists Explain Why It’s Necessary for Our Survival & Why We’re Biased Against It The Fat Acceptance movement may seem like a 21st century phenomenon, rising to public consciousness with the success of high-profile writers, actors, filmmakers, and activists in recent years. But the movement can date its origins to 1967, when WBAI radio personality Steve Post held a “fat-in” in Central Park, bringing 500 people together to protest, celebrate, and burn diet books and photos of Twiggy. “That same year,” notes the Center for Discovery, “a man named Llewelyn ‘Lew’ Louderback wrote an article for the Saturday Evening Post titled, ‘More People Should be FAT.’” These early sallies led to the founding of the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance (NAAFA) two years later and more radical groups in the 70s like the Fat Underground. There would be no need for fat activism, of course, if there were no biases against fat people. This raises the question: where did those biases come from? They are not innate, says Harvard University evolutionary biologist Daniel Lieberman in the Slate video above, but are a product of a history that tracks, coincidentally, with the rise of mass marketing and mass consumerism. We have been sold the idea that thin bodies are better, healthier, more attractive, and more desirable, and that fat is something to be warred against. “However, as an evolutionary biologist, “says Lieberman, I’ve come to appreciate that without fat, we’d be dead. Humans wouldn’t really be the way we are. Fat is really life.” A quick perusal of art history shows us that larger bodies have been valued around the world in much of human history. We now associate fat with poor health, but it has also signaled the opposite — a storehouse of caloric wealth and healthy fertility. “Our bodies have all sorts of tricks to make sure we never run out of energy,” says Lieberman, “and the main way that we store energy is fat.” Leiberman and other biologists in the video survey the role of fat in human survival and thriving. “Fat is an organ,” and scientists are learning how it communicates with other systems in the body to regulate energy consumption and feed our comparatively enormous brains. Among animals, “humans are especially adapted to be fat.” Even the thinnest among us are corpulent compared to most primates. Still, the average human did not have any opportunity to become obese until relatively recent historical developments — in the grand evolutionary scheme of things — like agriculture, heavy industry, and the science to preserve and store food. When Europeans discovered sugar, then mass produced it on plantations and exported it around the world, sugar consumption magnified exponentially. The average American now eats 100 pounds of sugar per year. The average hunter-gatherer might have struggled the eat “a pound or two a year” from natural sources. The over-abundance of calories has led to a type-II diabetes epidemic worldwide that is closely related to sugar consumption. It isn’t necessarily related to having a larger body, although fat deposits in the heart and elsewhere can worsen insulin resistance (and heart disease); the problem is almost certainly linked to excess sugar, the constant availability of high-calorie foods, and low incentives to exercise. Our hunger for sweets and love of comfort are not character flaws, however. They are evolutionary drives that allow us to acquire and conserve energy, operating in a food economy that often punishes us for those very drives. Dieting not only doesn’t work, as neuroscientist Sandra Aamodt explains in her TED Talk above, but it often backfires, making us even hungrier because our brains perceive us as deprived. As scientists like Lieberman gain a better understanding of the role of fat in human biology, those in the medical community are realizing that doctors and nurses are hardly free from the societal biases against fat. Studies show those biases can translate to poorer medical care and bad advice about dieting, a vicious cycle in which health conditions unrelated to weight go untreated, and are then blamed on weight. Evolutionary biology explains the role of fat in human development, and human history explains its increase, but the question of where the hatred of fat comes from is a trickier one for these scientists to answer. They barely mention the role of advertising and entertainment. In 1979, activists in the “Fat Liberation Manifesto” identified the problem as fat people’s “mistreatment by commercial and sexist interests” that have “exploited our bodies as objects of ridicule, thereby creating an immensely profitable market selling the false promise of avoidance of, or relief from, that ridicule.” Despite decades of resistance, the diet industry thrives. A Google search of the phrase “body fat” yields page upon page of unscientific advice about ideal body fat percentages, as though reminding the majority of Americans (7 in 10 are classified as overweight or obese) that they should feel there’s something wrong with them. Blame, shame, and ridicule won’t solve medical problems, say the biologists in the video above, and it certainly doesn’t help people lose weight, if that’s what they need to do. If we better understood the role of fat in keeping us healthy, happy, and alive, maybe we could overcome our hatred of it and accept others, and ourselves, in whatever bodies we’re in. Related Content: How the Food We Eat Affects Our Brain: Learn About the “MIND Diet” Exercise May Prove an Effective Natural Treatment for Depression & Anxiety, New Study Shows Why Sitting Is The New Smoking: An Animated Explanation Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Evolutionary History of Fat: Biologists Explain Why It’s Necessary for Our Survival & Why We’re Biased Against It is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | The Velvet Underground: Get a First Glimpse of Todd Haynes’ Upcoming Documentary on the Most Influential Avant-Garde Rockers To the question of the most influential band formed in the 1960s a list of easy answers unfolds, beginning with the Beatles, the Beach Boys, and the Rolling Stones. As three of the makers of the best-selling records of all time, those bands all lay fair claim to the title. But even within the commercial dynamo of postwar America, it was also possible to exert great influence without topping the charts, or indeed without even reaching them. This is proven by the story of avant-garde rockers the Velvet Underground, whose meager success in their day as compared with their formidable cultural legacy inspired Brian Eno to sum them up with a quip now so well-known as to have become a cliché. But not even a mind like Eno’s can truly sum up the Velvet Underground. Better to tell the band’s story — the story, in its way, of art and popular culture in mid-to-late 20th-century America — in a feature-length documentary, as Todd Haynes has done with The Velvet Underground, which premiered at this year’s Cannes Film Festival and debuts on AppleTV+ on October 15th. “Haynes appears to have vacuumed up every last photograph and raw scrap of home-movie and archival footage of the band that exists and stitched it all into a coruscating document that feels like a time-machine kaleidoscope,” writes Variety critic Owen Gleiberman. He introduces the Velvets and their associates “by playing their words off the flickering black-and-white images of their Warhol screen tests.” The Velvets were, in a sense, a product of Warhol’s Factory. The pop-art icon managed the band himself early on, connecting them with the singer who would become the second titular figure on their debut The Velvet Underground & Nico and designing that album’s oft-visually-referenced banana-sticker cover. Having died in 1987, Warhol couldn’t grant Haynes an interview; having followed Warhol the next year, neither could Nico. Band leader Lou Reed, too, has now been gone for the better part of a decade, but he does have plenty to say in the 1986 South Bank Show documentary above. Haynes’ The Velvet Underground includes Reed in archival footage, but also features new reminiscences from surviving members like Maureen Tucker and John Cale. Like all human beings, the Velvets are mortal; but their expansion of rock’s sonic possibilities will outlast us all. Related Content: A Symphony of Sound (1966): Velvet Underground Improvises, Warhol Films It, Until the Cops Turn Up The Velvet Underground Captured in Color Concert Footage by Andy Warhol (1967) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The Velvet Underground: Get a First Glimpse of Todd Haynes’ Upcoming Documentary on the Most Influential Avant-Garde Rockers is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

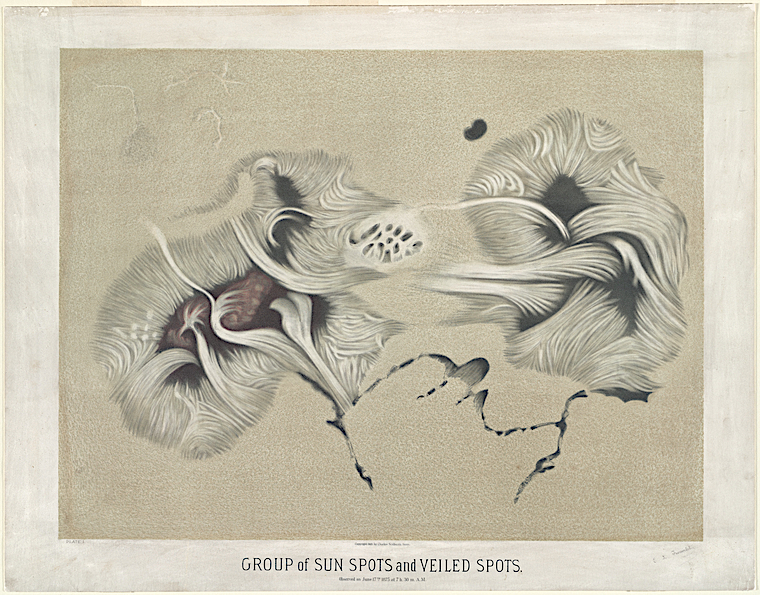

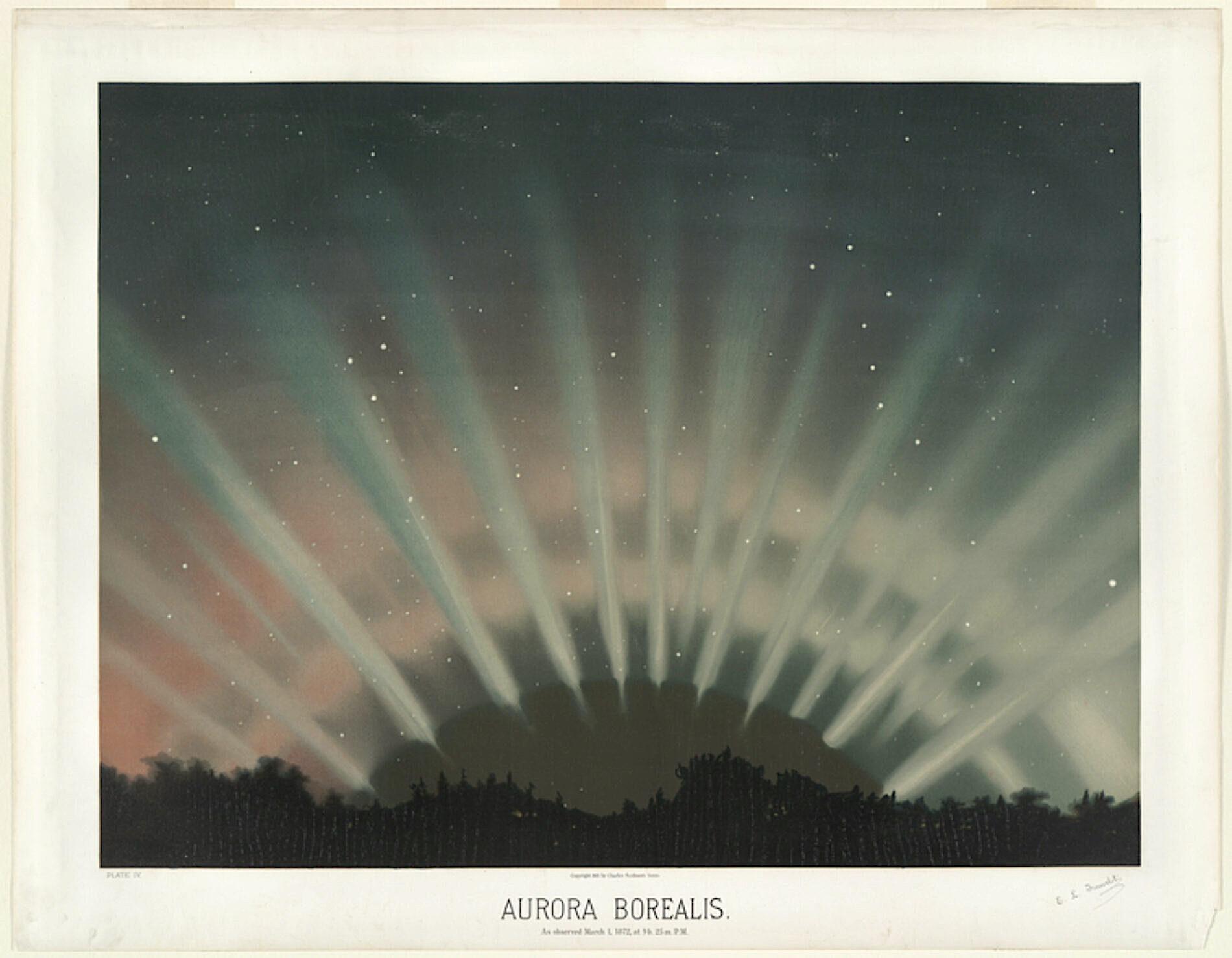

| 2:00p | The Brilliant 19th-Century Astronomical Drawings of Étienne Léopold Trouvelot

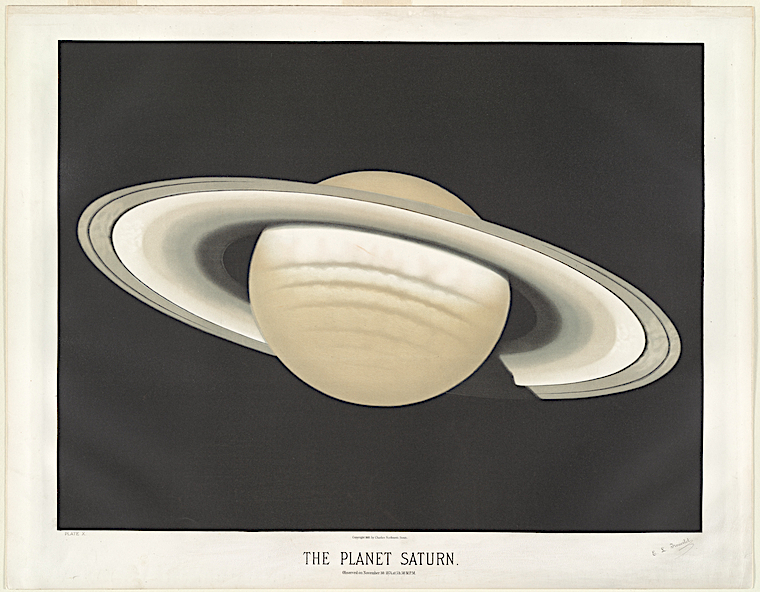

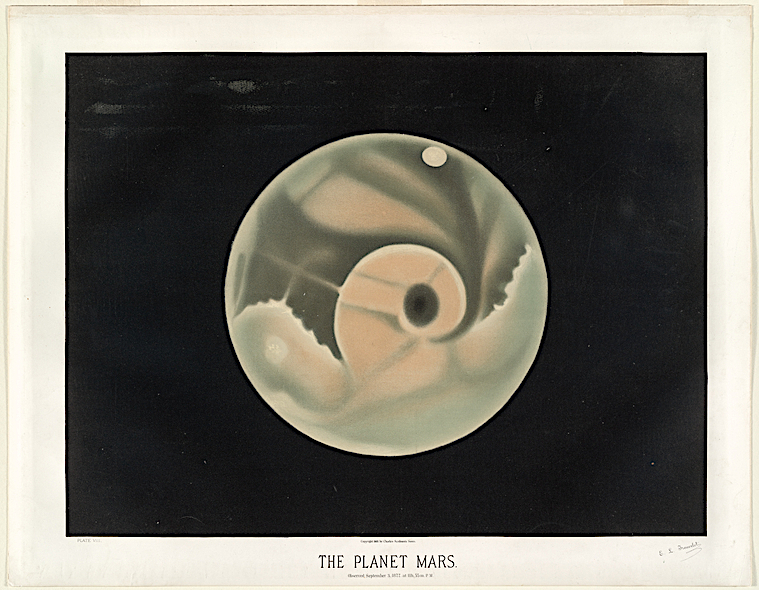

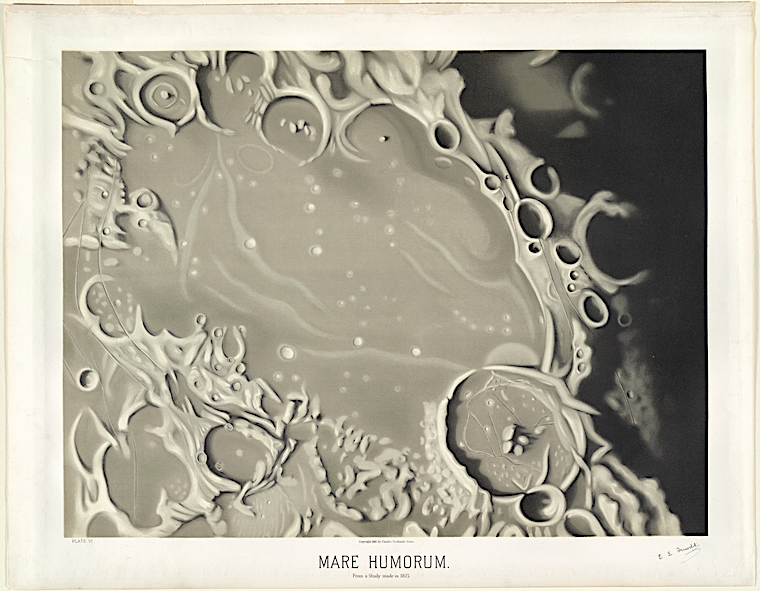

Trouvelot might have thought his scientific papers would be his legacy. He wrote fifty in his lifetime. Instead it is his roughly 7,000 illustrations of planets, comets, and other phenomena that still please us to this day. The New York Public Library has put 15 of his best up on their site, and over at this page, you can compare what Trouvelot saw—-the great astronomer Emma Converse called Trouvelot the “prince of observers”—-to photos from NASA’s archive. Even if his Mars is a bit fanciful, looking translucent like a fish egg, his understanding of the planet echoes in the following century of sci-fi paranoia. Something strange must be there, he suggests.

Harvard hired him to sketch at their college’s observatory, and he used pastels to bring the planets to life. Engraving or ink would not have worked as well as these soft shapes and determined lines. His rendering of the moon surface is accurate but also fanciful, like whipped cream. And his sun spots might not be accurate, but they replicated the god-like forces at work on its tumultuous surface. His Saturn is the most realistic of them all. Even the NASA image doesn’t look too different to Trouvelot’s art.

These images also help rehabilitate Trouvelot’s other legacy—-the dreaded Gypsy Moth. Before his stint as amateur scientist, he was also an amateur entomologist, and while researching silkworms and silk production, accidentally let European gypsy moths into North America, where they wreaked havoc on the forests of North America. Saturn’s rings may look the same back then as they do now, but so does the damage of the gypsy moth, which according to Wikipedia is up to $868 million in damages per year.

Related Content: A 9th Century Manuscript Teaches Astronomy by Making Sublime Pictures Out of Words Jocelyn Bell Burnell Changed Astronomy Forever; Her Ph.D. Advisor Won the Nobel Prize for It Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here. The Brilliant 19th-Century Astronomical Drawings of Étienne Léopold Trouvelot is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/09/02 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |