[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, September 13th, 2021

| Time | Event |

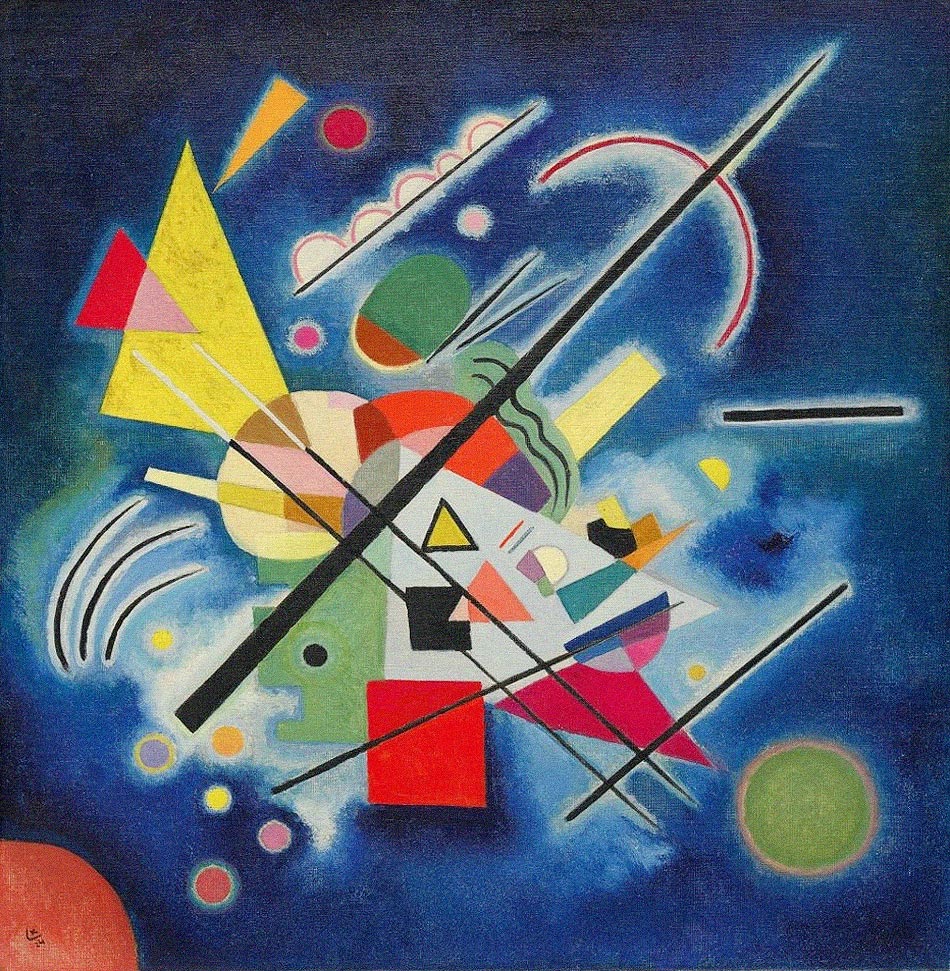

| 8:00a | The Evolution of Kandinsky’s Painting: A Journey from Realism to Vibrant Abstraction Over 46 Years

Like most renowned abstract painters, Wassily Kandinsky could also paint realistically. Unlike most renowned abstract painters, he only took up art in earnest after studying economics and law at the University of Moscow. He then found early success teaching those subjects, which seem to have proven too worldly for his sensibilities: at age 30 he enrolled in the Munich Academy to continue the study of art that he’d left off while growing up in Odessa. The surviving paintings he produced at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, displayed on Wikipedia’s list of his works, include a variety of landscapes, most presenting German and Russian (or today Ukrainian) landscapes undisturbed by a single human figure.

Kandinsky made dramatic change come with 1903’s The Blue Rider (above). The presence of the titular figure made for an obvious difference from so many of the images he’d created over the previous half-decade; a shift in its very perception of reality made for a less obvious one. This is not the world as we normally see it, and Kandinsky’s track record of highly representative paintings tells us that he must deliberately have chosen to paint it it that way. With fellow artists like August Macke, Franz Marc, Albert Bloch, and Gabriele Münter, he went on to form the Blue Rider Group, whose publications argued for abstract art’s capability to attain great spiritual heights, especially through color.

“Gradually Kandinsky makes departures from the external ‘world as a model’ into the world of ‘paint as a thing in itself,'” writes painter Markus Ray. “Still depicting ‘worldly scenes,’ these paintings start to take on purer colors and shapes. He reduces volumes into simple shapes, and colors into bright and vibrant hues. One can still make out the scene, but the shapes and colors begin to take on a life of their own.” This is especially true of the scenes Kandinsky painted in Bavaria, such as 1909’s Railway near Murnau above. The outbreak of World War I five years later sent him back to Russia, where he continued his pioneering journey toward a visual art equal in expressive power to music, which he called his “ultimate teacher.” But by the early 1920s it had become clear that his increasingly individualistic and non-representative tendencies wouldn’t sit well with the Soviet cultural powers that be.

A return to Germany was in order. “In 1921, at the age of 55, Kandinsky moved to Weimar to teach mural painting and introductory analytical drawing at the newly founded Bauhaus school,” says Christie’s. “There he worked alongside the likes of Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers,” and also expanded on Goethe‘s theories of color. A true believer in the Bauhaus’ “philosophy of social improvement through art,” Kandinsky also wound up among the artists whose work was exhibited in the Nazi Party’s “Degenerate Art Exhibition” of 1937. By that time the Bauhaus was dissolved and Kandinsky had resettled in Paris, where until his death in 1944 (as evidenced by Wikipedia’s list of his paintings) he kept pushing further into abstraction, seeking ever-purer expressions of the human soul until the very end.

Related Content: Time Travel Back to 1926 and Watch Wassily Kandinsky Make Art in Some Rare Vintage Video An Interactive Social Network of Abstract Artists: Kandinsky, Picasso, Brancusi & Many More How to Paint Like Kandinsky, Picasso, Warhol & More: A Video Series from the Tate The Guggenheim Puts Online 1700 Great Works of Modern Art from 625 Artists Take a Journey Through 933 Paintings by Salvador Dalí & Watch His Signature Surrealism Emerge Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. The Evolution of Kandinsky’s Painting: A Journey from Realism to Vibrant Abstraction Over 46 Years is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

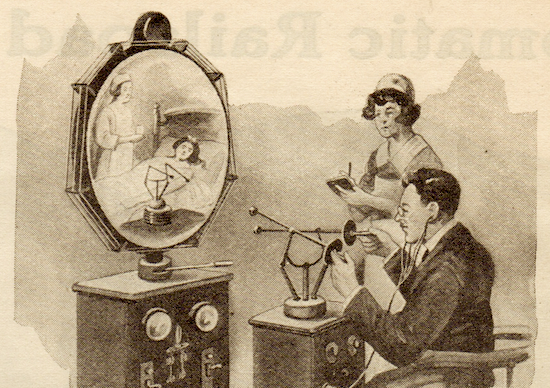

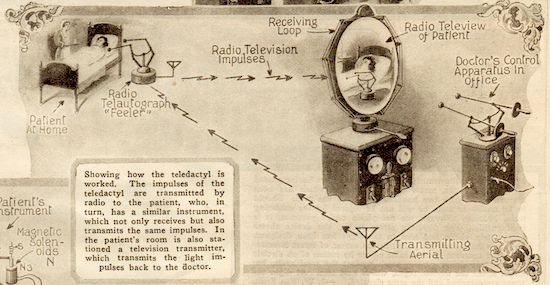

| 11:00a | Sci-Fi Pioneer Hugo Gernsback Predicts Telemedicine in 1925

If you’ve ever wondered why one of science fiction’s greatest honors is called the “Hugo,” meet Hugo Gernsback, one of the genre’s most important figures, a man whose work has been variously described as “dreadful,” “tawdry,” “incompetent,” “graceless,” and “a sort of animated catalogue of gadgets.” But Gernsback isn’t remembered as a writer, but as an editor, publisher (of Amazing Stories magazine), and pioneer of science fact, for it was Gernsback who first introduced the earth-shaking technology of radio to the masses in the early 20th century. “In 1905 (just a year after emigrating to the U.S. from Germany at the age of 20),” writes Matt Novak at Smithsonian, “Gernsback designed the first home radio set and the first mail-order radio business in the world.” He would later publish the first radio magazine, then, in 1913, a magazine that came to be called Science and Invention, a place where Gernsback could print catalogues of gadgets without the bother of having to please literary critics. In these pages he shone, predicting futuristic technologies extrapolated from the cutting edge. He was understandably enthusiastic about the future of radio. Like all self-appointed futurists, his predictions were a mix of the ridiculous and the prophetic. Case in point: Gernsback theorized in a 1925 Science and Invention article that communications technologies like radio would revolutionize medicine, in exactly the ways that they have in the 21st century, though not quite through the device Gernsback invented: the “teledactyl,” which is not a robotic dinosaur but a telemedicine platform that would allow doctors to examine, diagnose, and treat patients from a distance with robotic arms, a haptic feedback system, and “by means of a television screen.” Never mind that television didn’t exist in 1925. Sounding not a little like his contemporary Buckminster Fuller, Gernsback insisted that his device “can be built today with means available right now.”

It would require significant upgrades to radio technology before it could support the wireless internet that lets us meet with doctors on computer screens. Perhaps Gernsback wasn’t entirely wrong — technology may have allowed for some version of this in the early 20th century, if medicine had been inspired to move in a more sci-fi direction. But the focus of the medical community — after the devastation of the 1918 flu epidemic — had understandably turned toward disease cure and prevention, not distance diagnosis. Gernsback looked fifty years ahead, to a time, he wrote, when “the busy doctor… will not be able to visit his patients as he does now. It takes too much time, and he can only, at best, see a limited number today.” Home visits did not last another fifty years, but remote medicine didn’t take their place until almost 100 years after Gernsback wrote. Indeed, the webcams that now give doctors access to patients in the pandemic only came about in 1991 for the purpose of making sure the break room in the computer science department at Cambridge had coffee. Gernsback even anticipated advances in space medicine, which has spent the last several years building the technology he predicted in order to perform surgeries on sick and injured astronauts stuck months or years away from Earth. He would have particularly appreciated this usage, though he isn’t given credit for the idea. Gernsback also deserves credit for poking fun at himself, as he seemed to realize how hard it was for most people to take him seriously.

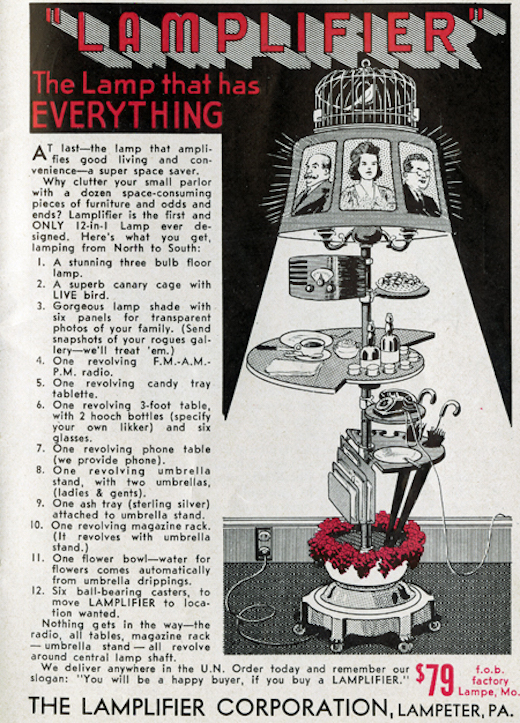

To non-visionaries, the technologies of the future would all seem equally ridiculous today, as in the pages of Gernsback’s satirical 1947 publication, Popular Neckanics Gagazine. Here, we find such objects as the Lamplifier, “the lamp that has EVERYTHING.” Gernsback’s love of gadgets blurred the boundaries between science fiction and fact, always with the strong suggestion that — no matter how useful or how ludicrous — if a machine could be imagined, it could be built and put to work. Related Content: A 1947 French Film Accurately Predicted Our 21st-Century Addiction to Smartphones Sci-Fi Author J.G. Ballard Predicts the Rise of Social Media (1977) Arthur C. Clarke Predicts in 2001 What the World Will Look By December 31, 2100 Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Sci-Fi Pioneer Hugo Gernsback Predicts Telemedicine in 1925 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | Art History School: Learn About the Art & Lives of Toulouse-Lautrec, Gustav Klimt, Frances Bacon, Edvard Munch & Many More Artist and videographer Paul Priestly is an enthusiastic and generous sort of fellow. His free online drawing tutorials abound with encouraging words for beginners, and he clearly relishes lifting the curtain to reveal his home studio set up and self designed camera rig. But we here at Open Culture think his greatest gift to home viewers are his Art History School profiles of well-known artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Vincent Van Gogh. An avid storyteller, he’s drawn to those with tragic histories — the decision to pivot from impersonating the artist, as he did with Van Gogh, to serving as a reporter interested in how such details as syphilis and alcoholism informed lives and careers is a wise one. Priestly makes a convincing case that Lautrec’s aristocratic upbringing contributed to his misery. His short stature was the result, not of dwarfism, but Pyknodysostosis (PYCD) a rare bone weakening disease that surely owed something to his parents’ status as first cousins. His appearance made him a subject of lifelong mockery, and ensured that the freewheeling artist scene in Montmartre would prove more welcoming than the blueblood milieu into which he’d been born. Priestly makes a meal of that Demi-monde, introducing viewers to many of the players. He heightens our appreciation for Lautrec’s masterpiece, At the Moulin Rouge, by briefly orienting us to who’s seated around the table: writer and critic Édouard Dujardin, dancer La Macarona, photographer Paul Secau, and “champagne salesman and debauchee” Maurice Guibert, who earlier posed as a lecherous patron in Lautrec’s At the Café La Mie. Queen of the Cancan La Goulue hangs out in the background with another dancer, the wonderfully named La Môme Fromage. Lautrec places himself squarely in the mix, looking very much at home. Consider that these names, like those of frequent Lautrec subjects acrobatic dancer Jane Avril and chanteuse Yvette Guilbert were as celebrated in Belle Epoque Montmartre as many of the painters Lautrec rubbed shoulders with — Degas, Pissarro, Cézanne, Van Gogh and Manet. In an article in The Smithsonian, Paul Trachtman recounts how Lautrec discovered the model for Manet’s famous nude Olympia, Victorine Meurent, “living in abject poverty in a top-floor apartment down a Montmartre alley. She was now an old, wrinkled, balding woman. Lautrec called on her often, and took his friends along, presenting her with gifts of chocolate and flowers — as if courting death itself.” Meanwhile Degas sniffed that Lautrec’s studies of women in a brothel “stank of syphilis.” Perhaps Priestly will delve into Degas for an upcoming Art History School episode … there’s no shortage of material there. Above are three more of Paul Priestly’s Art History School profiles that we’ve enjoyed on Frances Bacon, Edvard Munch and Gustav Klimt. You can subscribe to his channel here. Related Content: Art Historian Provides Hilarious & Surprisingly Efficient Art History Lessons on TikTok Free Art & Art History Courses Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday. Art History School: Learn About the Art & Lives of Toulouse-Lautrec, Gustav Klimt, Frances Bacon, Edvard Munch & Many More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/09/13 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |