[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, September 29th, 2021

- “Is Social Media Ruining Comedy?” by Ian Crouch

- “Comedy from a Distance” by Misha Rajani

- “Laugh Out Loud, Virtually” by Shreya Veronica

- “How 5 Chicago Standup Comics Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Zoom” by Doug George

| Time | Event |

| 7:01a | Stand-Up Comedy in the Internet Age — Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #106

Your host Mark Linsenmayer discusses how Internet culture has changed stand-up with three comedians: past Pretty Much Pop guests Rodney Ramsey (who co-owns the Unknown Comedy Club) and Daniel Lobell (host of Modern Day Philosophers and author of the Fair Enough comic), plus Dena Jackson (also a speaker on yoga and mindfulness and host of The Ego Podcast). How does the existence of YouTube, social media, and virtual spaces changed the way comedians construct a set, relate to their fans, and make a living? We talk about story-telling vs. one-liners, repping your hometown, comedy cliques, surviving negativity, and more. Some articles that go into these issues further include: Follow @TheUnknownVenue, @Denatalks, and @DanielLobell. This episode includes bonus discussion you can access by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop or by choosing a paid subscription through Apple Podcasts. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts. Stand-Up Comedy in the Internet Age — Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #106 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 8:00a | Why Scientists Can’t Recreate the Sound of Stradivarius Violins: The Mystery of Their Inimitable Sound In his influential 1936 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” critic Walter Benjamin used the word “aura” to describe an artwork’s “presence in time and space” — an explanation of the thrill, or chill, we get from standing before a Jackson Pollock, say, or a Michelangelo, rather than a photograph of the same. Writing in the age of radio, photography, and newspapers, Benjamin believed that aura could not be transmitted or copied: “Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element” — that rare thing that makes art worth preserving and reproducing in the first place. Let’s grant, for the sake of argument, that musical instruments have aura — that the very sounds they make are its manifestation, and that, no matter how sophisticated our technology, we may never reproduce those sounds perfectly. As Hank Green explains in the SciShow video above: “For centuries, musicians, instrument makers, engineers, and scientists have been trying to understand and reproduce the ‘Stradivarius’ sound. They’ve investigated everything from the materials their maker used to how he crafted the violins. But the mystique is still there.” Can science solve the mystery? At heart, the question seems to be whether the aural qualities of a Stradivari instrument can be plucked from their time and place of origin and made fungible, so to speak, across the centuries. Antonio Stradivari (his name is often Latinized to “Stradivarius”) began making violins in the 1600s and continued, with his sons Francesco and Omobono, until his death in 1737, producing around 1000 instruments, most of which were violins. About 650 of those instruments survive today, and approximately 500 of those are violins, ranging in value from tens of millions to priceless. Green surveys the techniques, materials, physics, and chemical composition of Stradivari violins “to understand why Stradivarius violins have been so hard to recreate.” Their sound has been described as “silvery,” says Green, a word that sounds pretty but has little technical meaning. Rather than rely on adjectives, researchers from diverse fields have tried to work from the objects themselves — analyzing and attempting to recreate the violins’ shape, construction, materials, etc. They’ve learned that time and place matter more than they supposed. The wood of a Stradivari violin “really is different,” Green says, “but because Stradivari never wrote down his process, researchers can’t quite tell why.” That wood itself grew in a process over which Stradivari had no control. The alpine spruce he used came from trees harvested “at the edge of Europe’s Little Ice Age, a 70-year period of unseasonably cold weather … that slowed tree growth and made for even more consistent wood.” We begin to see the difficulties. One researcher, Joseph Nagyvary, a professor emeritus of biochemistry at Texas A&M University, recently made another discovery. As Texas A&M Today notes:

Perhaps we cannot duplicate the sound because none of us is Antonio Stradivari, working with his sons in the early 18th century in Cremona, Italy, building violins with a unique crop of alpine spruce while fighting unseasonably cold weather and worms. Related Content: Why Stradivarius Violins Are Worth Millions Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Why Scientists Can’t Recreate the Sound of Stradivarius Violins: The Mystery of Their Inimitable Sound is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

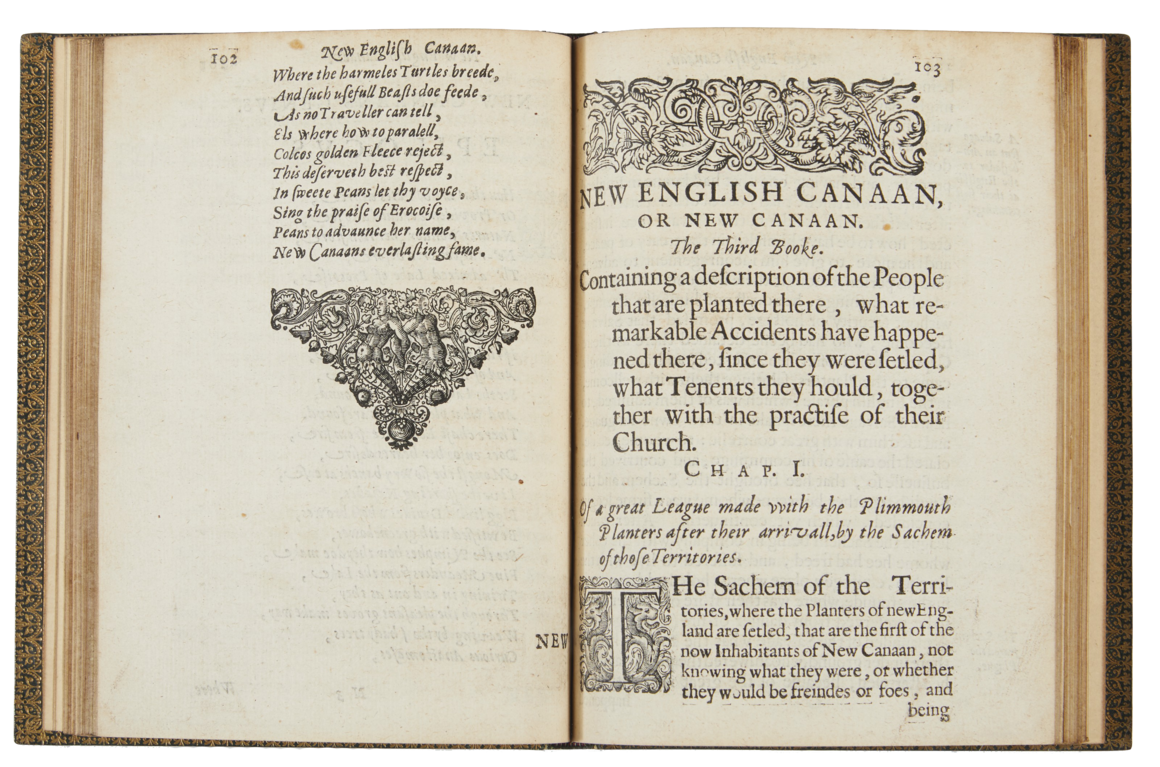

| 11:00a | America’s First Banned Book: Discover the 1637 Book That Mocked the Puritans

In the contest for the title of the most American historical figure of them all, Thomas Morton‘s name can’t be left out. Businesslike, litigious, given to rhapsodies over nature, and not resistant to turning celebrity, he was also — in a characteristically American manner — born elsewhere. Back in Devon, England, he’d made his name as a lawyer, representing members of the lower class in court, but in 1622 he was hired by investor Sir Ferdinando Gorges on a trip to handle his affairs in the North American colonies. This was just two years after the founding of Plymouth Colony, whose success had inspired many an English businessman to contemplate getting in on the New World action himself. In 1624, Gorges sent Morton across the Atlantic again, this time with everything needed to found a colony of his own. Morton was not a Puritan, nor was he “on board with the strict, insular, and pious society they had hoped to build for themselves,” as Atlas Obscura’s Matthew Taub puts it. Though his own colony of Merrymount became Plymouth’s rival in the fur trade, for the Puritans “the problem wasn’t only that Morton was taking goods and commerce away from Plymouth, but that he was giving that business to the Native Americans, including trading guns to the Algonquins. With Plymouth’s monopoly dissolved and its perceived enemies armed, Morton had perhaps done more than anyone else to undermine the Puritan project in Massachusetts.” And that was before Morton erected Merrymount’s 80-foot, antler-topped maypole, around which he invited residents to “drink, dance, and frolic.” Obviously, Morton’s reign as a “lord of misrule” (as Plymouth’s governor William Bradford deemed him) could not be borne for long. “During the 1628 festivities, a Puritan militia led by Myles Standish invaded Merrymount and chopped down the maypole,” writes Taub, noting that the incident inspired Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1832 short story “The May-Pole of Merry Mount.” Morton also turned out to be an able chronicler of the period himself, at least after the subsequent tribulations that saw him sentenced to death by starvation, helped to survive by the Native American tribes with whom he had maintained good relations, safely returned to England, and frustrated in his attempts to return to the colonies. Around 1630, he did what any true American, official or aspiring, would do: put together a lawsuit. Morton demanded, writes World History Encyclopedia’s Joshua Mark, “that the government of the Massachusetts Bay Colony demonstrate by what authority they exercised their power,” arguing for the revocation of its charter “because the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay Colony had not only misrepresented themselves in obtaining the charter but had no right to colonize the region in the first place as it was legally in Gorges’ patent.” As the long (and in any case futile) legal proceedings dragged on, Morton got the idea of turning his extensive briefs for the trial into “a three-volume work of history, natural history, satire, and poetry” called New English Canaan, a Biblical allusion underscoring Morton’s critical view of the Puritans as “abusing the natives and the land for profit and then justifying their actions in the name of their god and the scriptures.” Linda Cantoni at Hot off the Press writes that “the first two books of New English Canaan are mostly non-controversial, containing Morton’s observations on the native Americans, whom he respected greatly, and on the rich natural resources in New England. It was in the third book that Morton rolled up his sleeves and got down to his real purpose of skewering the New England Puritans, who, he said, ‘make a great shewe of Religion, but no humanity.'” As a result, writes Mental Floss’ Jake Rossen, “his book was perceived as an all-out attack on Puritan morality, and they didn’t take kindly to it. So they banned it,” making New English Canaan what Christie’s called “America’s first banned book” when they auctioned a copy off for $60,000. But you can read it for free at Project Gutenberg, bearing in mind the most American lesson of all from the life of Thomas Morton: when all else fails, publish a tell-all memoir. via Atlas Obscura Related Content: The British Library Digitizes Its Collection of Obscene Books (1658-1940) Read 14 Great Banned & Censored Novels Free Online: For Banned Books Week 2014 When Christmas Was Legally Banned for 22 Years by the Puritans in Colonial Massachusetts Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. America’s First Banned Book: Discover the 1637 Book That Mocked the Puritans is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | Nirvana Refuses to Mime Along to “Smells Like Teen Spirit” on Top of the Pops (1991)   This month marks the 30th anniversary of Nirvana’s Nevermind, first released on September 24, 1991, “the day,” writes Michael Tedder at Stereogum, “that college radio-nurtured types and arty hard rock officially became rebranded as Alternative Rock, and, according to legend, everything changed forever.” You might believe that legend even if you remember the reality. Yes, “Smells Like Teen Spirit” was just as huge as everybody says — and, yes, you likely recall where you were when you first saw the video or heard the song explode with Pixies-inspired quiet-loud ferocity from the radio. But the change was already on the way. Nirvana emerged in a pop music landscape slowly becoming saturated with alternative music. You might also remember where you were the first time you saw the video for Depeche Mode’s “Enjoy the Silence,” for example, or R.E.M.’s “Losing My Religion,” or Sinéad O’Connor’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” — or when you first experienced the dynamic/melodic assault of the aforementioned Pixies, virtual alt-rock elders by the time they released Trompe Le Monde, their fourth studio album, in the same September week that Nevermind appeared. (You may remember where you were the first time you heard the word “Lollapalooza,” first organized in 1991.) The fateful week in September also saw the release of 90s-defining albums like Primal Scream’s Screamadelica, Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Blood Sugar Sex Magik, and A Tribe Called Quest’s Low End Theory. In the year that Nevermind supposedly single-handedly invented “grunge,” Soundgarden released Badmotorfinger and Pearl Jam released Ten. It’s fair to say Nirvana were one of just many bands reinventing themselves and the culture. Even the hair metal bands and teen pop idols Nirvana put out of business were already trying to make more serious, “authentic” music before Nevermind turned every executive’s head. Kurt Cobain was already well aware — and wary — of the dangers of hero worship and blind allegiance to style over substance. It was an attitude he came by naturally given that, in 1991, his friends in Olympia, Washington founded an indie record label called Kill Rock Stars. He’d written an anthem, “In Bloom,” about it before anyone heard the opening power chords of “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” As he pursued, with rigorous ambition, the power of rock stardom, he rejected its trappings and pretensions, as when the band appeared on Top of the Pops and took the piss out of the show, rather than mime along dutifully, as Mark Beaumont writes at NME:

In light of the groundswell of alternative bands emerging — or still plugging away — at the time of Nevermind’s release, the myth of Nirvana as the single-handed inventors of 90s alt-rock is more than a little overblown. This is especially so in a decade that saw electronic dance music and hip hop cross over into rock and vice-versa, a trend Nirvana had nothing to do with. They were a thunderingly great band, and Kurt Cobain was a rare and gifted songwriter, but the heart of Nirvana’s popular appeal was extra-musical. The band — meaning, principally, Cobain — most honestly embodied the spirit of the time: painfully ambivalent and at war with its aspirations. “Kurt — I would call him a windmill,” says bassist Krist Novoselic. “He wanted to be a rock star — and he hated it.” Related Content: The Recording Secrets of Nirvana’s Nevermind Revealed by Producer Butch Vig The Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain’s Headbanging Cover of Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness Nirvana Refuses to Mime Along to “Smells Like Teen Spirit” on Top of the Pops (1991) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/09/29 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |