[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, October 20th, 2021

| Time | Event |

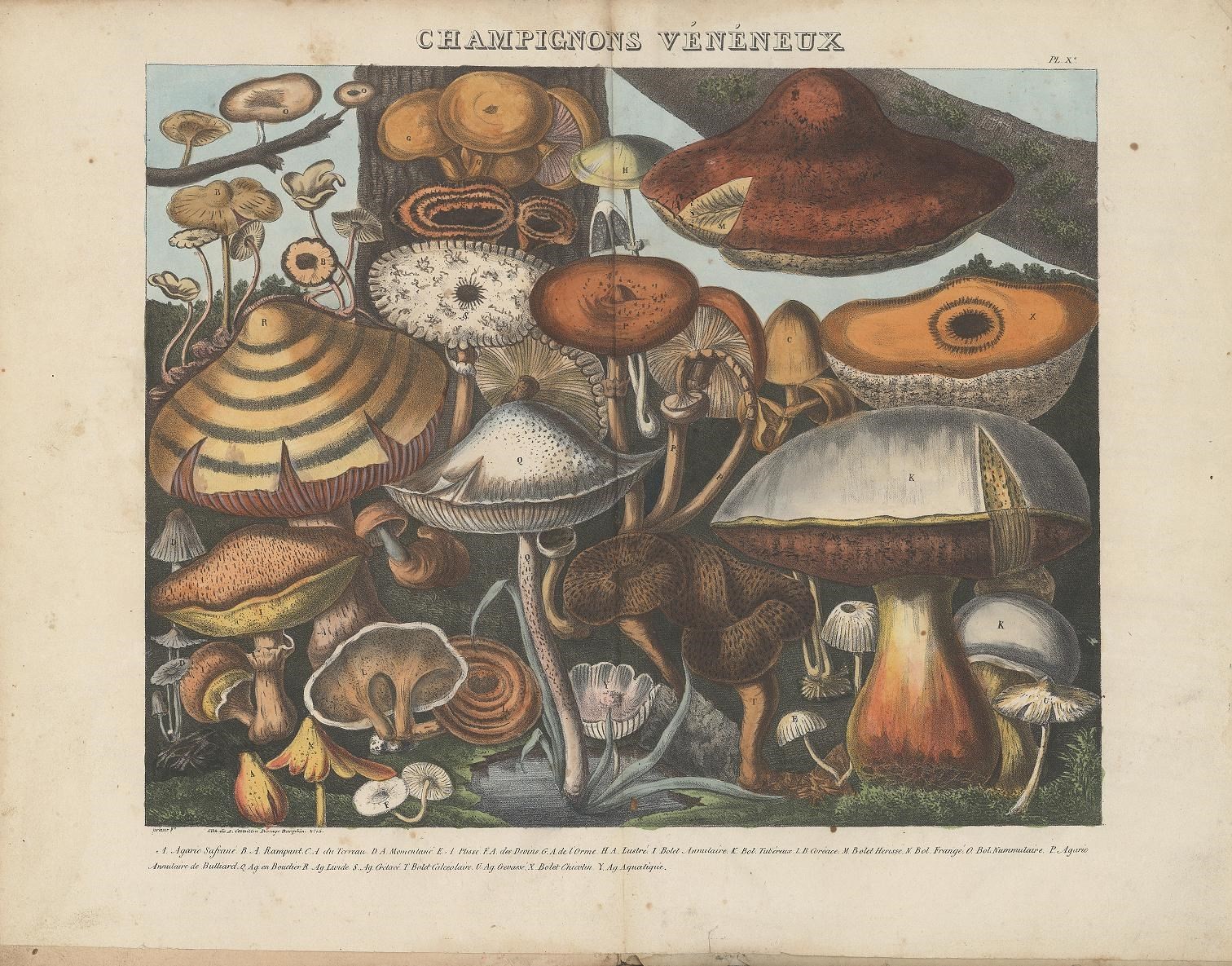

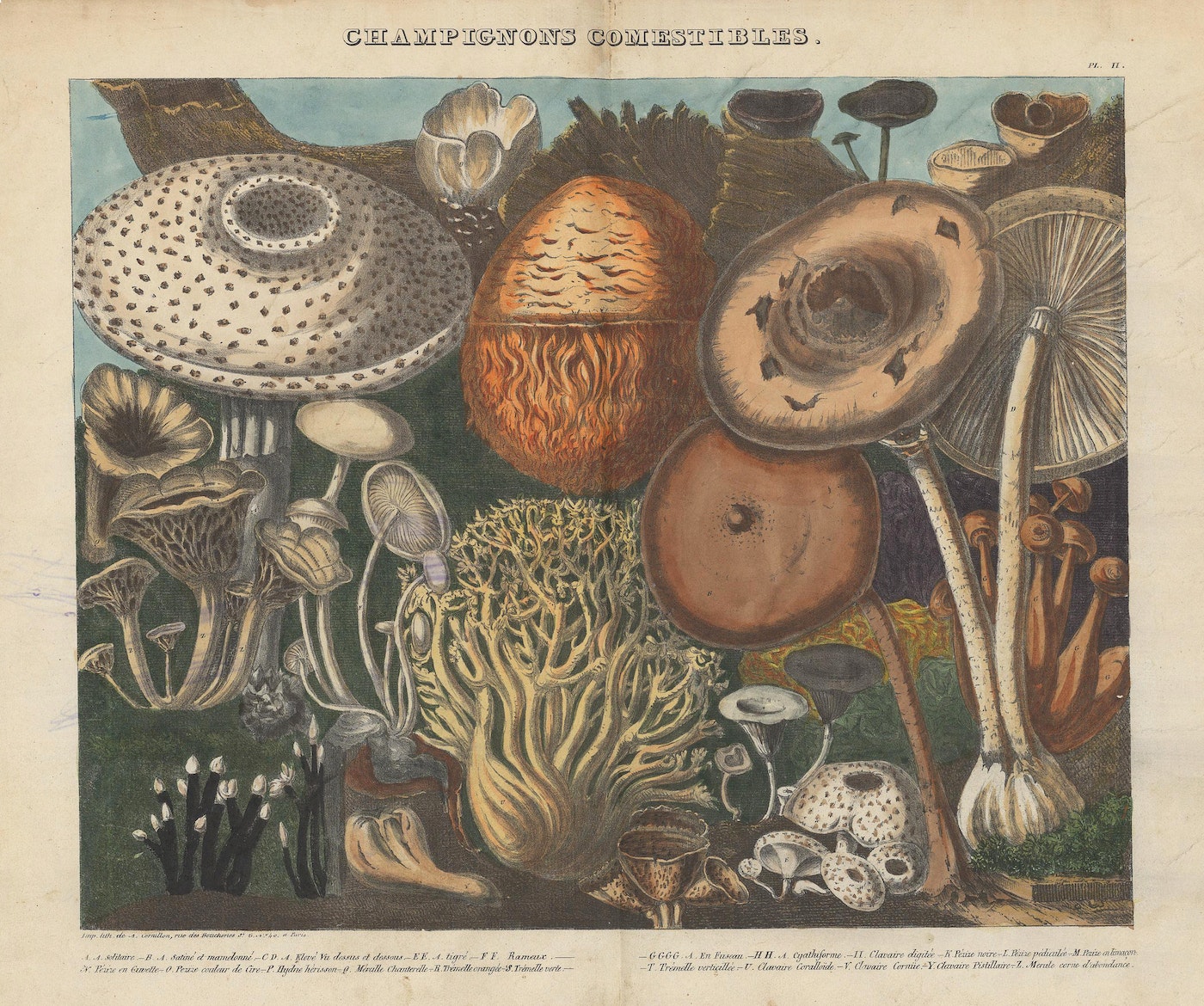

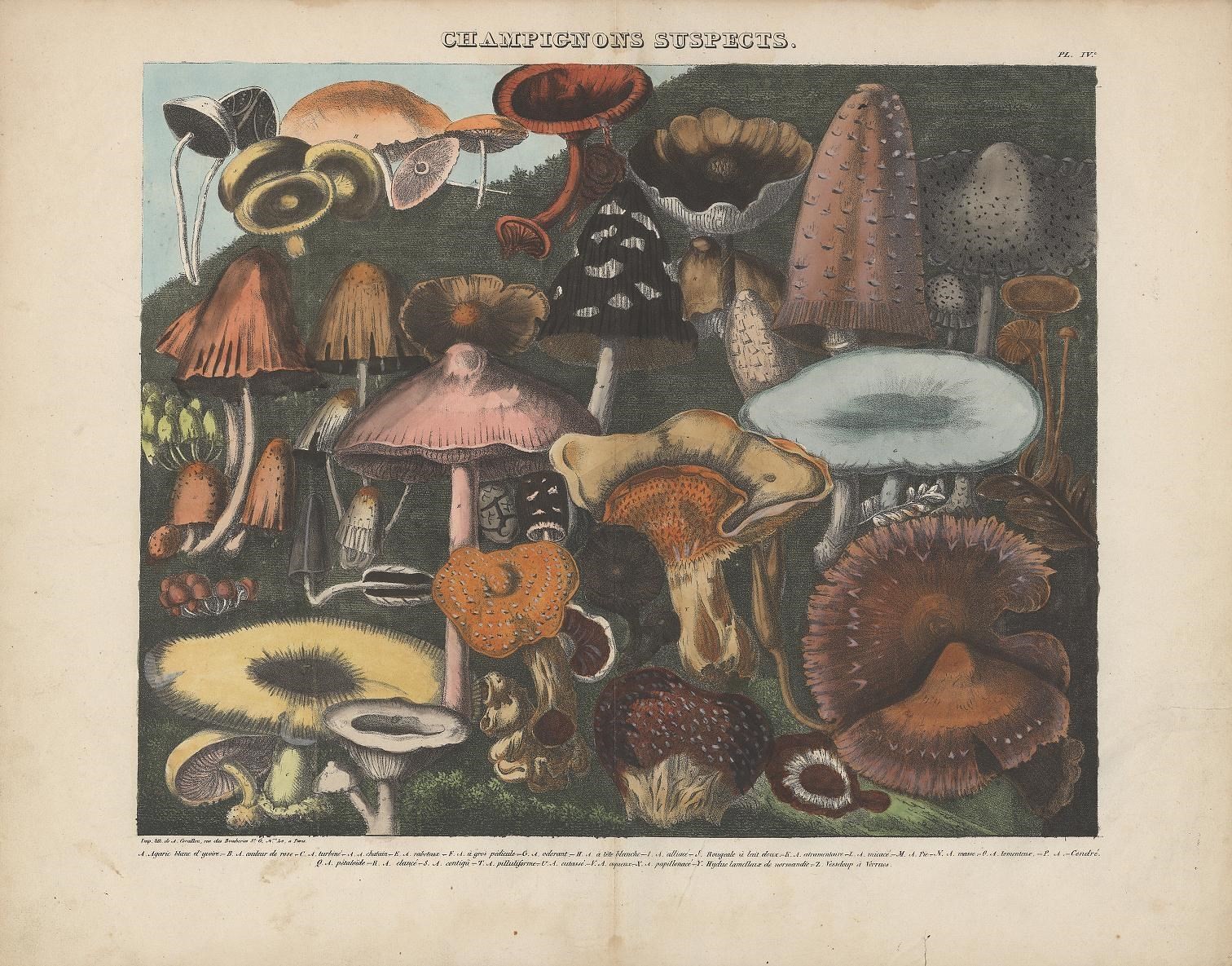

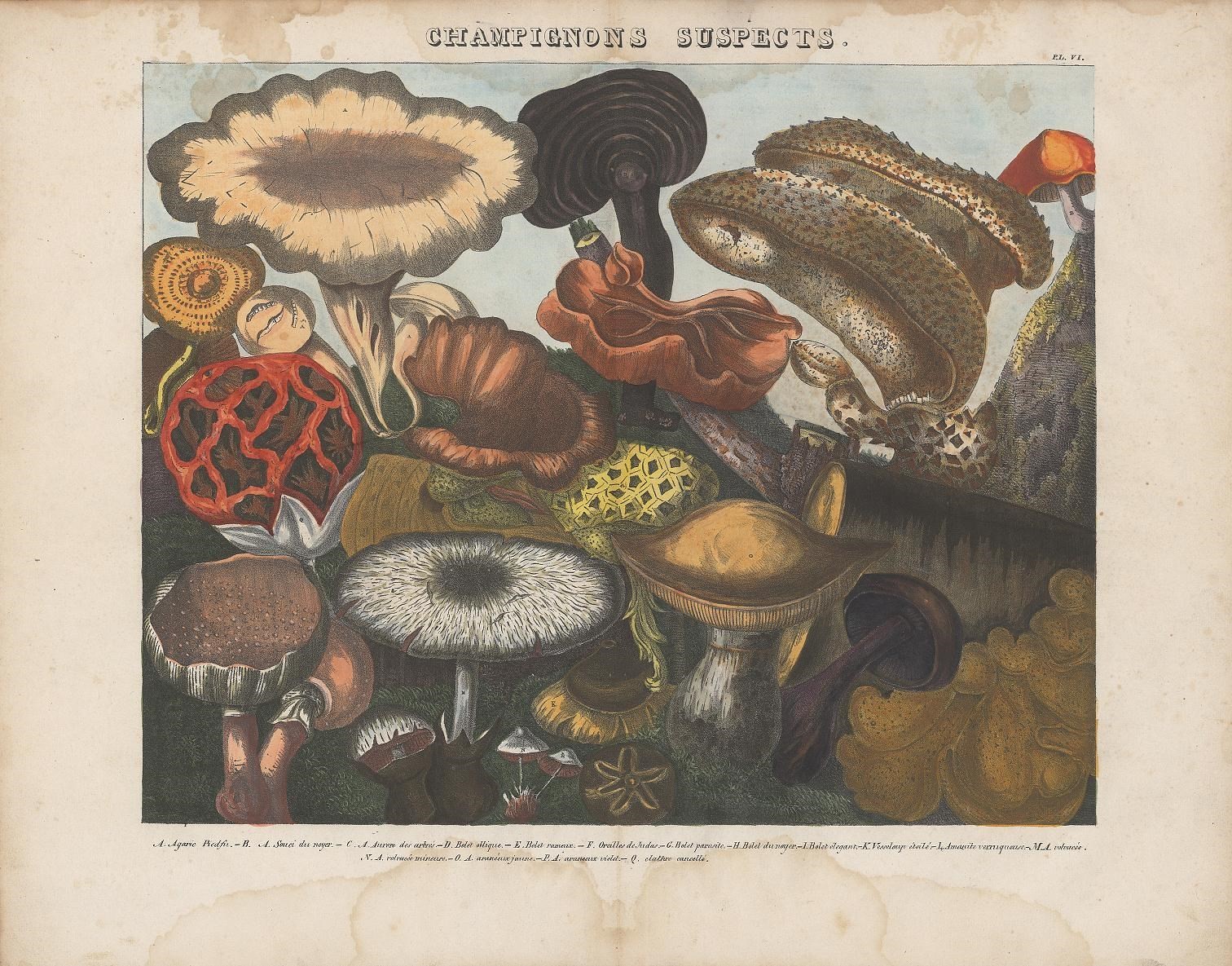

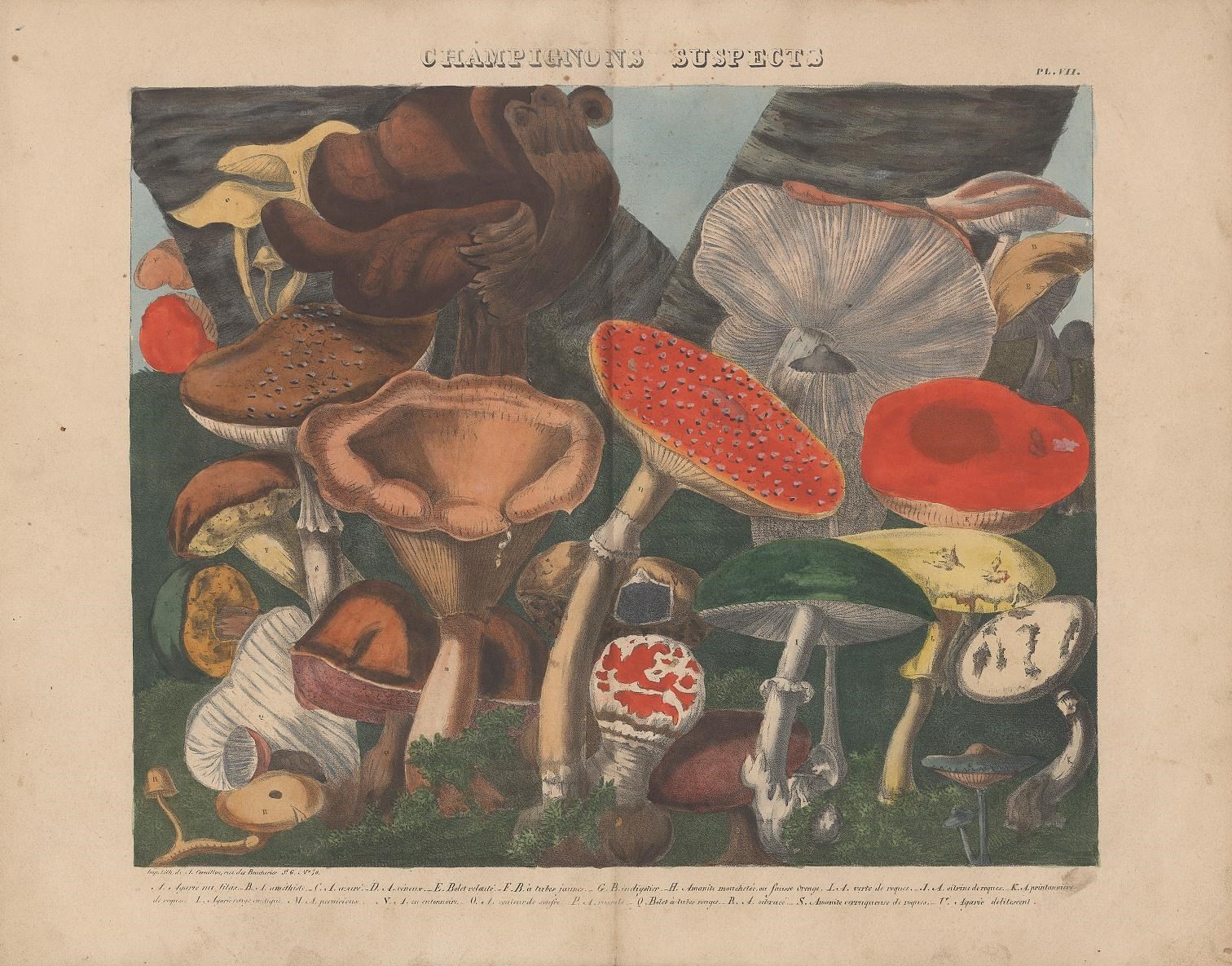

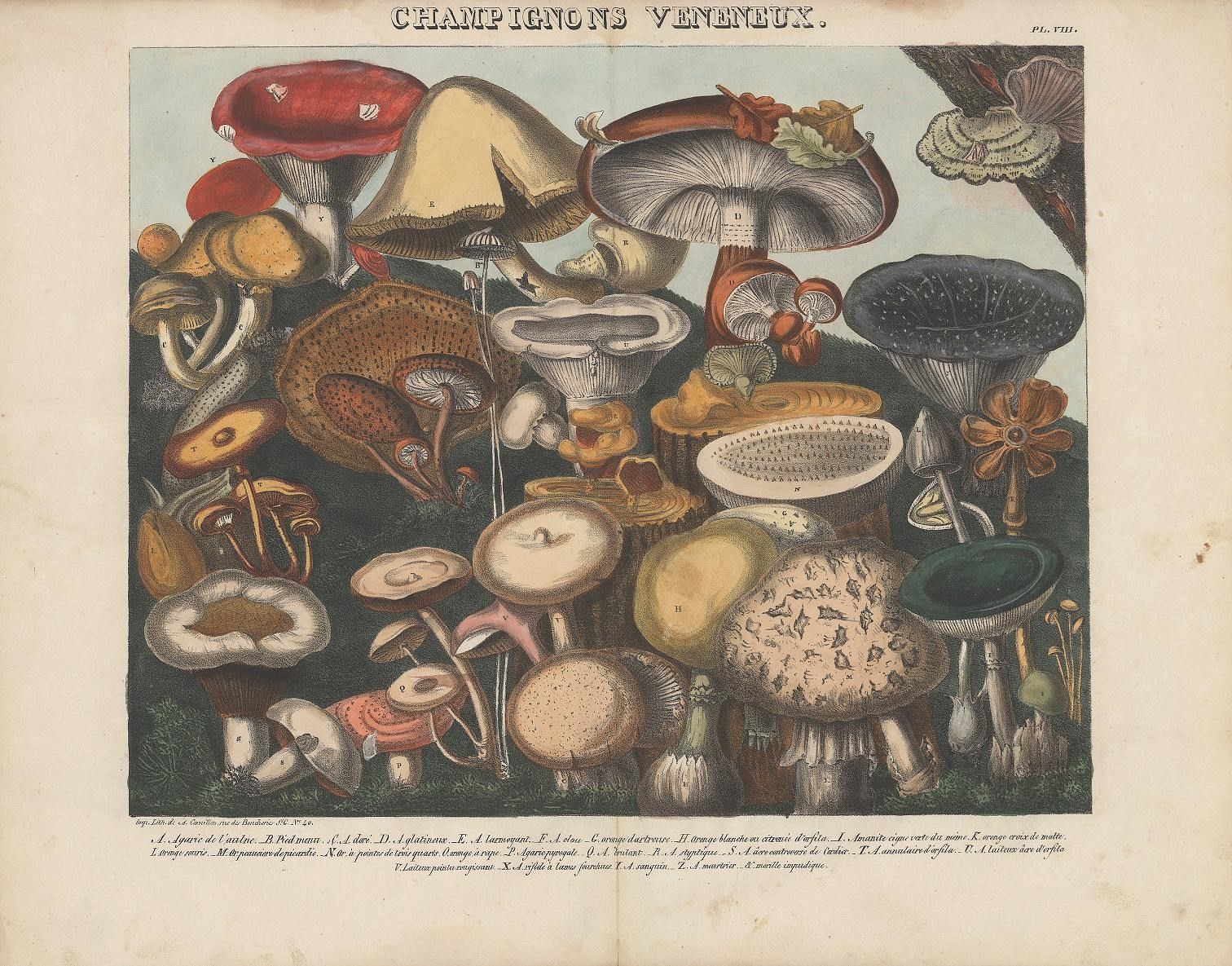

| 8:00a | The Beautifully Illustrated Atlas of Mushrooms: Edible, Suspect and Poisonous (1827)

Two centuries ago, Haiti, “then known as Saint-Domingue, was a sugar powerhouse that stood at the center of world trading networks,” writes Philippe Girard in his history of the Haitian war for independence. “Saint-Domingue was the perle de Antilles… the largest exporter of tropical products in the world.” The island colony was also at the center of the trade in plants that drove the scientific revolution of the time, and many a naturalist profited from the trade in slaves and sugar, as did planter, “physician, botanist, and inadvertent historiographer of the Haitian Revolution” Michel Etienne Descourtilz, the Public Domain Review writes.

Descourtilz’ 1809 Voyages d’un naturaliste “chronicles, among other adventures, a trip from France to Haiti in 1799 in order to secure his family’s plantations.” Instead, he was arrested and conscripted as a doctor under Jean-Jacques Dessalines. The experience did not change his view that the island should be reconquered, though he did admit “the germ” of rebellion “must secretly have existed everywhere there were slaves.” Decourtilz chiefly spent his time, while not attending to those wounded by Napoleon’s army, collecting plants between Port-au-Prince and Cap-Haïtien.

In the dense tropical growth along the Artibonite river, now part of the border between Haiti and Cuba, Decourtilz learned much about the plant world — and maybe learned from some Haitians who knew more about the island’s flora than the Frenchman did. Rescued in 1802, Decourtilz returned to France with his plants and began to compile his research into taxonomic books, including Flores pittoresque et medicale des Antilles, in eight volumes, and a later, 1827 work entitled Atlas des champignons: comestibles, suspects et vénéneux, or “Atlas of mushrooms: edible, suspect and poisonous.”

As the title makes clear, sorting out the differences between one mushroom and another can easily be a matter of life and death, or at least serious poisoning. “Fly agaric, for example,” writes the Public Domain Review, “can resemble edible species of blushers.” Consumed in small amounts, it might cause hallucinations and euphoria. Larger doses can lead to seizures and coma. One can imagine the numbers of colonists in the French Caribbean who either had very bad trips or were poisoned or killed by unfamiliar plant life. Just last year alone in France, hundreds were poisoned from misidentified mushrooms.

To guide the mushroom hunter, cook, and eater, Decourtiliz’s book featured these rich, colorful lithographs here by artist A. Cornillon (which may remind us of the proto-psychedelic scientific art of Ernst Haeckel). He alludes to the great dangers of wild mushrooms in a dedication to “S.A.R., Duchesse de Berry” and promises his guide will prevent “mortal accidents” (those which “frequently occur among the poor.”) Descourtilz offers his guide, accessible to all, he writes, out of a devotion to the alleviation of human suffering. Read his Atlas of Mushrooms, in French at the Internet Archive, and see more of Cornillon’s illustrations here.

Related Content: 1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness The Beautifully Illustrated Atlas of Mushrooms: Edible, Suspect and Poisonous (1827) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 11:00a | When Salvador Dali Viewed Joseph Cornell’s Surrealist Film, Became Enraged & Shouted: “He Stole It from My Subconscious!” (1936) Did Salvador Dalí meet the diagnostic criteria for a personality disorder and maybe, also, a form of psychosis, as some have alleged? Maybe, but there’s no real way to know. “You can’t diagnose psychiatric illnesses without doing a face to face psychiatric examination,” Dutch psychiatrist Walter van den Broek writes, and it’s possible Dali “consciously created an ‘artistic’ personality… for the money or in order to succeed.” No doubt Dalí was a tireless self-promoter who marketed his work by way of a sensationalist persona. But maybe Dalí faked symptoms of mental illness (via his understanding of Freud) in order to deliberately induce states of psychosis as part of his paranoid-critical method, a “spontaneous method of irrational knowledge based on the critical and systematic objectivity of the associations and interpretations of delirious phenomena,” he wrote. One of Dalí’s extreme “unorthodox methods for idea generation,” the practice of pretending to be insane may have driven Dalí to believe too strongly in his own delusions at times. Throughout the early 1930s, Dalí championed paranoia, “a form of mental illness in which reality is organized in such a manner so as to be served through the control of an imaginative construction,” he said in a 1930 lecture. “The paranoiac who thinks he is being poisoned discovers in all the things that surround him, down to their most imperceptible and subtle details, preparations for his death.” And the paranoiac Surrealist who believes he’s being robbed of his ideas may see artistic theft everywhere — especially in an exhibit of Surrealist artists that does not include him. (After all, as Dalí once declared, “I am Surrealism.”) In 1936, Dalí attended a screening of Joseph Cornell’s short Surrealist film Rose Hobart (top), named for the obscure silent actress whose scenes Cornell excised from a “1931 jungle adventure film” called East of Borneo. Cornell took the footage, slowed it down, “chopped it up, reordered it, and discarded the entire plot,” writes Catherine Corman. “He cut out reaction shots… removed overtly upsetting scenes,” edited in scenes from other films, and “made the film seem deliberately modest and worn,” projecting it through a blue filter and scoring it with two songs from Nestor Amaral’s album Holiday in Brazil (which he’d found at a junk shop). The screening happened to be held in New York at the same time as the Museum of Modern Art’s first exhibit of Surrealist art, an exhibition “rife with controversy,” MoMA writes, that “provoked fierce reactions from battle factions among the Dadaists and the Surrealists.” French Surrealist poet and critic André Breton, who two years earlier expelled Dalí from the Surrealist group for “the glorification of Hitlerian fascism,” wrote the catalogue introduction. The Spanish Civil War had just broken out that year, further aggravating Dalí, no doubt, when he encountered Cornell’s film at a matinee screening. Partway through the screening of Rose Hobart, Dalí became enraged, stood up, shouting in Spanish, and overturned the projector. Later, he reportedly told Julian Levy, whose gallery held the screening: “My idea for a film is exactly that, and I was going to propose it to someone who would pay to have it made…. I never wrote it or told anyone, but it is as if [Cornell] had stolen it.” Other versions of the story had Dalí saying, “He stole it from my subconscious!” or “He stole my dreams!” Cornell had not, of course, reached into Dalí’s subconscious but had manifested the film from his own obsessions with silent film and Hollywood divas, themes that run throughout his work. After Dalí’s outburst, the shy, reclusive artist refused to screen Rose Hobart again until the 1960s. Dalí had vanquished an imaginary rival, but perhaps his true targets — Breton and his former Surrealist colleagues — remained untouched. It would not matter: Dalí eclipsed them all in fame, especially in the age of television, which embraced the artist’s antics like no other medium. But through his performances of insanity, maybe Dalí actually did touch into a creative preconscious state shared among artists — a place in which Joseph Cornell just might have found and stolen his ideas. In 1932, Dalí had an epiphany about Jean-Francois Millet’s The Angelus, a painting with which he’d been obsessed since childhood and that influenced him heavily as an adult, becoming a key source for his paranoid-critical method. Dalí claimed that the two farmers praying over a meager harvest were actually mourning a lost child. He persisted in this belief until the Louvre agreed to X-ray the painting. Underneath, they found a small, child-sized coffin, and at least one of Dalí’s morbid, paranoid fantasies was confirmed. Related Content: Take a Journey Through 933 Paintings by Salvador Dalí & Watch His Signature Surrealism Emerge When Salvador Dalí Created a Surrealist Funhouse at New York World’s Fair (1939) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness When Salvador Dali Viewed Joseph Cornell’s Surrealist Film, Became Enraged & Shouted: “He Stole It from My Subconscious!” (1936) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 2:00p | Mozart Sonatas Can Help Treat Epilepsy: A New Study from Dartmouth Many and bold are the claims made for the power of classical music: not just that it can enrich your aesthetic sensibility, but that it can do everything from deter juvenile delinquency to boost infant intelligence. Making claims for the latter are CDs with titles like Baby Mozart: Music to Stimulate Your Baby’s Brain, a case of trading on the name of one of the most beloved composers in music history. Alas, the proposition that classical music in general can make anyone smarter has yet to pass the most rigorous scientific trials. But recent research does suggest that Mozart’s music in particular has desirable effects on the brain: his Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major on epilepsy-afflicted brains in particular. For about 30 years the piece has been thought to reduce symptoms of epilepsy in the brain, a phenomenon known as the “K448 effect” (the number being a reference to its place in the Köchel catalogue). Recent work by researchers at the Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (DHMC) and Dartmouth College’s Bregman Music and Affective Sound Lab has gone deep into the workings of that effect, and you can read the results free online: the paper “Musical Components Important for the Mozart K448 Effect in Epilepsy,” published just last month in Nature. What they’ve found suggests that the K448 effect is real: that the piece is effective, to be more specific, in “reducing ictal and interictal epileptiform activity.” Writing for non-neuroscientists, Madeleine Mudzakis at My Modern Met explains that when the researchers “played the tune while monitoring brain implant sensors in the subjects,” they detected “events known as interictal epileptiform discharges (IEDs). These brain events are a symptom of epilepsy and are harmful to the brain.” But “after 30 seconds of listening to the sonata, the subjects experienced noticeably fewer IEDs,” and “transitions between musical phases lead to larger effects, possibly because of anticipation being created which culminates in the pleasant nature of a shifted tune.” These neurologically soothing qualities may also have something to do with the pleasure all Mozart aficionados, epileptics or otherwise, feel when they hear the Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major — or what they don’t feel when they hear Wagner, whose music was here employed as the control that every proper scientific experiment needs. Related Content: Hear All of Mozart in a Free 127-Hour Playlist Mozart’s Diary Where He Composed His Final Masterpieces Is Now Digitized and Available Online How Music Can Awaken Patients with Alzheimer’s and Dementia Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. Mozart Sonatas Can Help Treat Epilepsy: A New Study from Dartmouth is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/10/20 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |