[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, November 8th, 2021

- “The Board Games That Ask You to Reenact Colonialism” by Luke Winkie

- “Board Games Are Getting Really, Really Popular” by Darron Cummings

- “8 Historical Board Games, from Diverse Designers, That Show Great Promise” by Charlie Hall

- “How a Board Game About Birds Became a Surprise Blockbuster” by Dan Kois

- “How Classic Board Games Are Bringing Families Closer During the Pandemic” by Drew Weisholtz

- “Keep Your Game Night Rolling (At A Safe Distance) With These 3 Online Services” by Petra Mayer

| Time | Event |

| 8:01a | Board Game Ideology — Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #108

As board games are becoming increasingly popular with adults, we ask: What’s the relationship between a board game’s mechanics and its narrative? Does the “message” of a board game matter? Your host Mark Linsenmayer is joined by game designer Tommy Maranges, educator Michelle Parrinello-Cason, and ex-philosopher Al Baker to talk about re-skinning games, designing player experiences, play styles, game complexity, and more. Some of the games we mention include Puerto Rico, Monopoly, Settlers of Catan, Sorry, Munchkin, Sushi Go, Welcome To…, Codenames, Pandemic, Occam Horror, Terra Mystica, chess, Ticket to Ride, Splendor, Photosynthesis, Spirit Island, Escape from the Dark Castle, and Wingspan. Some articles that fed our discussion included: The two games Tommy created that we bring up are Secret Hitler and Inhuman Conditions. This episode includes bonus discussion you can access by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop or by choosing a paid subscription through Apple Podcasts. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network. Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts. Board Game Ideology — Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #108 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 9:00a | Watch the Jackson 5’s First Appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show (1969) Who discovered the Jackson 5? Motown founder Berry Gordy? Empress of Soul Gladys Knight? Diva Diana Ross? Everyone in attendance for Amateur Night at the Apollo on August 13, 1967? For many unsuspecting Americans, the answer may as well have been television host Ed Sullivan, who introduced the “sensational group” of five young brothers from Gary, Indiana to viewers in December 1969, two years after their Amateur Night triumph. Thirteen years earlier, a wall of sound emanating from a live in-studio audience of teenage girls told Sullivan’s home viewers that another young sensation — Elvis Presley — must be something special. The Jackson 5 needed no such help. While there are many close-ups of their fresh young faces, the control room wisely chose to zoom out much of the time, in appreciation of the brothers’ precision choreography. The brightest star was the youngest, eleven-year-old Michael, taking lead vocals in purple fedora and fringed vest on a cover of Sly and the Family Stone’s “Stand.” Jackie, Tito, Jermaine, and Marlon provide support for a bit of hokum that positions Michael at the center of an elementary school romance, by way of introduction to a full throated cover of Smokey Robinson’s “Who’s Loving You”: We toasted our love during milk break. I gave her my cookies! We fell out during fingerpainting. Author Carvell Wallace reflects on this moment in his 2015 New Yorker review of Steve Knopper’s biography MJ: The Genius of Michael Jackson: Halfway through, he forgets his lines and freezes, looking back at his older brothers for help. It’s an alarmingly vulnerable moment, one only possible in the era of live television. You feel bad for him. It suddenly doesn’t seem right that a kid should be made to perform live in front of an entire country. Yet he somehow finds his way back and stumbles through. When the music starts, we see something else entirely. The first note he sings is as confident, sure, and purposeful as any adult could ever be. He transforms from nervous child at a talent show into timeless embodiment of longing. Not only does he sing exactly on key but he appears to sing from the very bottom of his heart. He stares into the camera, shakes his head, and blinks back tears in perfect imitation of a sixties soul man. And it feels, for a moment, as though there are two different beings here. One is a child—a smart kid, to be sure, and cute, but not more special than any other child. He is subject to the same laws of life—pain, age, confusion, fear—as we all are. The other being seems to be a spirit of sorts, one who knows only the truest expression of human feeling. And this spirit appears to have randomly inhabited the body of this particular mortal kid. In so doing, it has sentenced him to a lifetime of indescribable enchantment and consummate suffering. Michael’s explosive performance of the Jackson 5’s first national single, “I Want You Back,” released just two months before their Sullivan Show appearance, gives us that “spirit” in full force. It’s also not hard to imagine that the brothers’ thrillingly executed choreography is the result of a literally punishing rehearsal regimen, a factor of the King of Pop’s troubled legacy. The Sullivan Show appearance ensured that there would be no stopping this train. Five months later, when the Jacksons returned to the Sullivan Show, “I Want You Back” had sold over a million copies, as had “ABC,” which they performed as a medley. Boyhood is fleeting, making Jacksonmania a carpe diem type situation. The period from 1969 to 1972 saw an onslaught of Jackson 5-related merch and a funky Saturday morning cartoon whose pilot tarted up the Diana Ross origin story with an escaped pet snake. It was good while it lasted. Related Content: Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primaologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday. Watch the Jackson 5’s First Appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show (1969) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| 3:00p | John Cleese Presents His 5-Step Plan for Shorter, More Productive Meetings (1976) Let’s face it, meetings are boring at best and at worst, chaotic, volatile, and potentially violent. And let’s also face it: to get through life as functioning adults, we’re going to have to sit through one or two of them — or even one or two of them a week. Maybe we’re the one who calls the meetings, and maybe they all feel like a waste of time. One solution is to have more informal meetings. This can be especially tempting in the age of work-from-home, when it’s impossible to know how many meeting attendees are wearing pants. Fewer rules can raise the spontaneity quotient, but allowing for the unexpected can invite disaster as well as epiphany. On the other end of the scale, we have the formality of parliamentary rules of order, such as those introduced by U.S. Army officer Henry Martyn Robert in 1876. Robert, whose father was the first president of Morehouse College, gained a wealth of experience with unproductive meetings as he traveled around the country with the Army. One particular meeting became a defining experience, as one account has it:

Sadly, this sort of thing has become almost routine at town halls and school board meetings. But it needn’t be so at the office. Nor, says John Cleese in the brief video above, do meetings need to follow the formality of parliamentary procedure. Cleese’s rules are simpler even than the simplified Roberts or Rosenberg’s Rules of Order, an even more simplified version of Robert’s Rules. Furthermore, Cleese avoids using words like “Rules” which can be a turn-off in our egalitarian times. Instead, he presents us with a “5-Step Plan” for holding better and shorter meetings.

Easy, right? Well, maybe not so easy in practice, but these steps can, at the very least, illuminate what’s wrong with your meetings, which may currently resemble one of Cleese’s many parodies of business culture. Nobody videophoned it in at the time, but trying to figure out who’s supposed to be doing what can still take up an afternoon. Let Cleese’s five steps bring order to the chaos. Related Content: Monty Python’s John Cleese Creates Ads for the American Philosophical Association John Cleese’s Very Favorite Comedy Sketches Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness John Cleese Presents His 5-Step Plan for Shorter, More Productive Meetings (1976) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

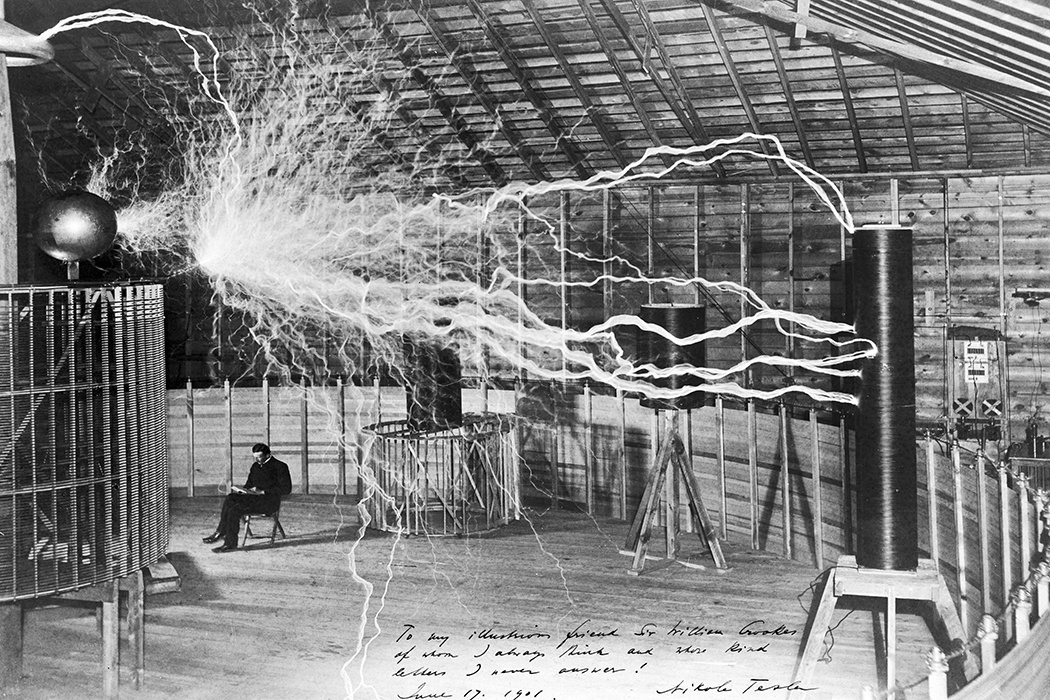

| 8:00p | When Nikola Tesla Claimed to Have Invented a “Death Ray,” Capable of Destroying Enemies 250 Miles Away & Making War Obsolete

Just last week I visited Niagara Falls and beheld the noble-looking statue of Nikola Tesla installed there. It struck me as a fitting tribute to the inventor of the Death Ray. But then, its presence probably had more to do with Tesla’s having advised the builders of the falls’ power plant to use two-phase alternating current, the form of electricity of which he’s now remembered as a pioneer. And in any case, Tesla never actually invented a death ray, or at least he never demonstrated one. He did, however, claim to have been working on a system he called “teleforce,” which shot what he described as a “death beam” — rays, he insisted, would never be feasible — both “thinner than a hair” and powerful enough to “destroy anything approaching within 200 miles,” making warfare effectively obsolete. These pronouncements attracted special media attention in the 1930s. “Hype about the weapon really took off in the run-up to World War II as Nazi Germany assembled a fearsome air force,” writes Sam Kean at the Science History Institute. “People in Tesla’s homeland, then called Yugoslavia, begged him to return home and install the rays to protect them from the Nazi menace.” But no known evidence suggests that the elderly Tesla had figured out how to actually make teleforce work. At that point he had more pressing problems, not least the cost of the hotels in which he lived. “In 1915, his famous Wardenclyffe tower plant was sold to help pay off his $20,000 debt at the Waldorf-Astoria,” writes Mental Floss’ Stacy Conradt, and later he racked up a similarly large bill at the Governor Clinton. “He couldn’t afford the payment, so instead, Tesla offered the management something priceless: one of his inventions.” That “invention” may have been the box examined after Tesla’s death in 1943 by physicist John G. Trump (uncle of former President Donald Trump). Left in a hotel vault, it was rumored to be “a prototype of his death ray.” Tesla had included a note, writes Kean, that “claimed the prototype inside was worth $10,000. More ominously, it said the box would detonate if opened incorrectly.” But when “the physicist steeled himself and began tearing off the brown paper,” he “must have laughed at what he saw underneath: a Wheatstone bridge, a tool for measuring electrical resistance. It was a common, mundane device — some old junk, really. It was certainly not a death ray, not even close.” Though it must have been as powerful a disappointment as it was a relief, did that discovery prove that Tesla never invented a death ray? The U.S. government didn’t take its chances on the matter: as History.com’s Sarah Pruitt tells it, agents “swooped in and took possession of all the property and documents from his room at the New Yorker Hotel” right after Tesla’s death. And “while the FBI originally recorded some 80 trunks among Tesla’s effects, only 60 arrived in Belgrade,” home of the Nikola Tesla Museum, nearly a decade later. The idea of death rays has long survived Tesla himself, taking on forms from the Reagan administration’s “Star Wars” nuclear defense program to the military laser weapons tested in recent years. Few such technologies seem capable of ending all war, as Tesla promised. But if one ever does, we could honor his memory by referring to it, in the manner he preferred, as not a death ray but a death beam. Related Content: In 1926, Nikola Tesla Predicts the World of 2026 The Electric Rise and Fall of Nikola Tesla: As Told by Technoillusionist Marco Tempest Nikola Tesla Accurately Predicted the Rise of the Internet & Smart Phone in 1926 Mark Twain Plays With Electricity in Nikola Tesla’s Lab (Photo, 1894) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. When Nikola Tesla Claimed to Have Invented a “Death Ray,” Capable of Destroying Enemies 250 Miles Away & Making War Obsolete is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs. |

| << Previous Day |

2021/11/08 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |