[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, February 14th, 2022

| Time | Event |

| 3:00p | How the Riot Grrrl Movement Created a Revolution in Rock & Punk The Riot Grrrl movement feels like one of the last real revolutions in rock and punk, and not just because of its feminist, anti-capitalist politics. As Polyphonic outlines in his short music history video, Riot Grrrl was one of the last times anything major happened in rock music before the internet. And it’s especially thrilling because it all started with *zines*. Women in the punk scene had a right to complain. Bands and their fans were very male, and sexual harassment was chronic at shows, leaving most women standing at the back of the crowd. Some zines even spelled it out: “Punks Are Not Girls,” says one. Alienated from the scene but still fans at heart, Tobi Vail and Kathleen Hanna, already producing their own feminist zines, joined forces to release “Bikini Kill” a gathering of lyrics, essays, confessionals, appropriated quotes, plugs for Vail’s other zine “Jigsaw“, and a sense that something was happening. Something was changing in rock culture. Kim Deal of the Pixies and Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth were heroes, Poly Styrene of X-Ray Spex was a legend, and Yoko Ono “paved the way in more ways than one for us angry grrl rockers.” Another zine, “Girl Germs,” was created by Allison Wolfe and Molly Neuman. Bikini Kill the zine led to Bikini Kill the band in 1990, and their song “Rebel Girl” became an anthem of a new feminist rock movement focused mainly in the Pacific Northwest, around the same time as grunge. Wolfe and Neuman, joined by Erin Smith, formed Bratmobile in 1991. K Records founder Calvin Johnson had asked them to play support for Bikini Kill, and out of necessity—Wolfe first admitted they were a “fake band”—they grabbed rehearsal space and became a “real” band on the spot. “Something in me clicked,” Wolfe said. “Like, okay, if most boy punk rock bands just listen to the Ramones and that’s how they write their songs, then we’ll do the opposite and I won’t listen to any Ramones and that way we’ll sound different.” The burgeoning scene needed a manifesto, and it got one in “Bikini Kill” issue #2. The Riot Grrrl Manifesto staked out a space that was against “racism, able-bodieism, ageism, speciesism, classism, thinism, sexism, anti-semitism and heterosexism” as well as “capitalism in all its forms.” It ends with: “BECAUSE I believe with my wholeheartmindbody that girls constitute a revolutionary soul force that can, and will change the world for real.” The manifesto (and the very healthy Pacific Northwest live scene) spawned a movement, even bringing with it bands that had been around previously, like L7. Riot Grrrl set out to elevate women’s voices and music, without capitulating to male standards, and return to the DIY and collective energy of the early punk scene. It also brought feminist theory out of the colleges and onto the stage, and with it queer theory and dialog about trauma, rape, and abuse—everything mainstream culture would rather not talk about. Like the original punk scene in the 1970s, it burned brightly and flamed out. But it inspired generations of bands, from Sleater-Kinney to White Lung, as well as non-rock music like the Electroclash movement. Read a zine from the time, or listen to the lyrics of Riot Grrrl bands and you will hear the same discourse, and recognize the same tactics, as today. In some ways it feels even more radical now-—that humble, photocopied zines could affect a whole scene and not be atomized by social media. To delve deeper, check out the New York Times‘ Riot Grrl Essential Listening Guide. Related Content: 33 Songs That Document the History of Feminist Punk (1975-2015): A Playlist Curated by Pitchfork Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here. |

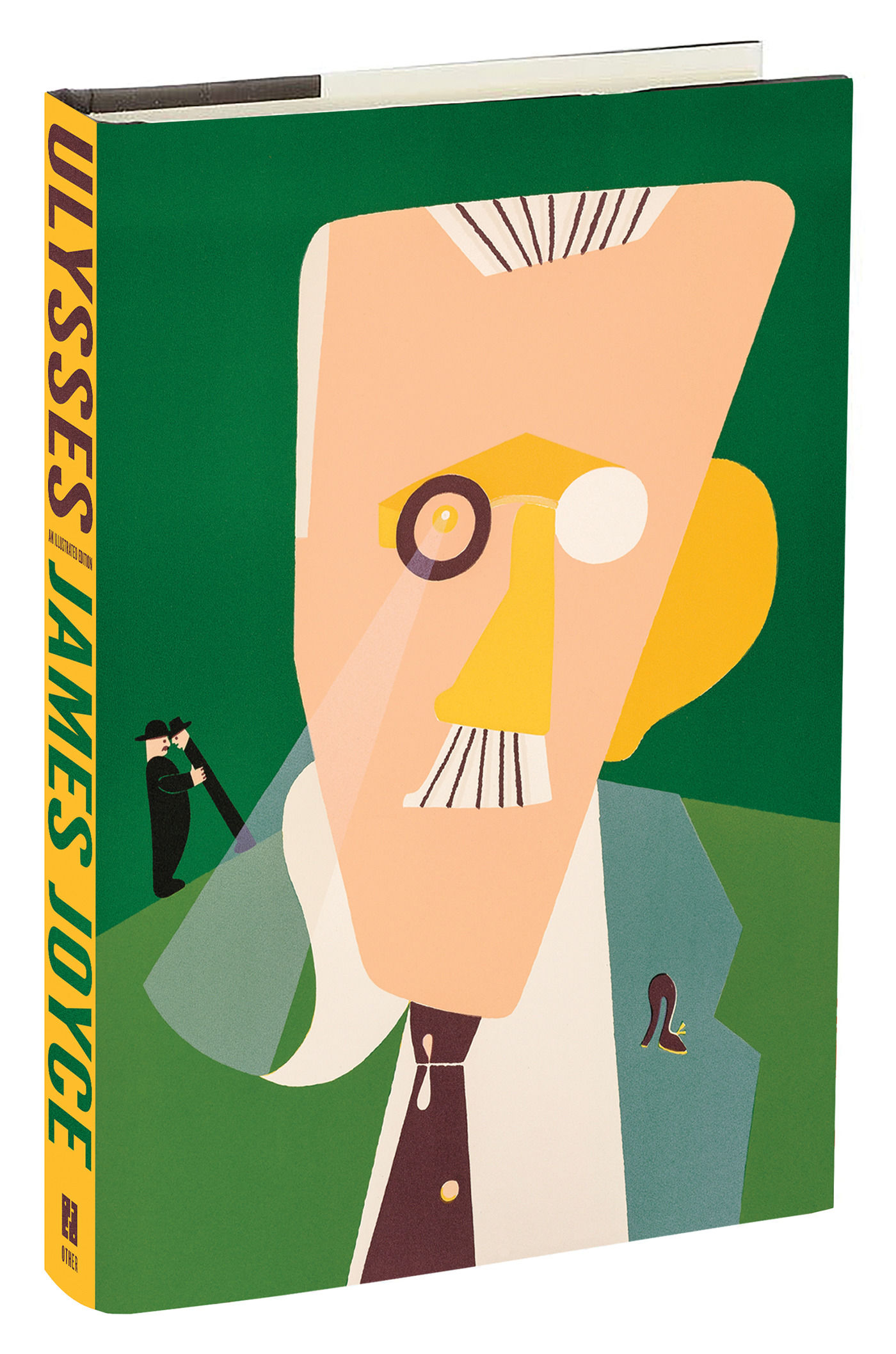

| 4:35p | The First Illustrated Edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses Gets Published, Featuring the Work of Spanish Artist Eduardo Arroyo

This year will see the long-delayed publication of a version of Ulysses that Joyce didn’t want you to read — not James Joyce, mind you, but the author’s grandson Stephen Joyce. Up until his death in 2020, Stephen Joyce opposed the publication of his grandfather’s best-known book in an illustrated edition. But he only retained the power actually to prevent it until Ulysses‘ 2012 entry into the public domain, which made the work freely usable to everyone who wanted to. In this case, “everyone” includes such notables as neo-figurative artist Eduardo Arroyo, described by the New York Times‘ Raphael Minder as “as one of the greatest Spanish painters of his generation.”

At the time of Ulysses‘ copyright expiration, Arroyo had long since finished his own set of more than 300 illustrations for Joyce’s celebrated and famously intimidating novel. Arroyo noted in a 1991 essay, writes Minder, that “imagining the illustrations kept him alive when he was hospitalized in the late 1980s for peritonitis, an inflammation of the abdominal lining.” The initial hope was for an Arroyo-illustrated edition to mark the 50th anniversary of Joyce’s death in 1991, but without the permission of the author’s estate, the project had to be put on hold for a couple of decades. When that time came, it was taken up again by two publishers, Barcelona’s Galaxia Gutenberg and New York’s Other Press.

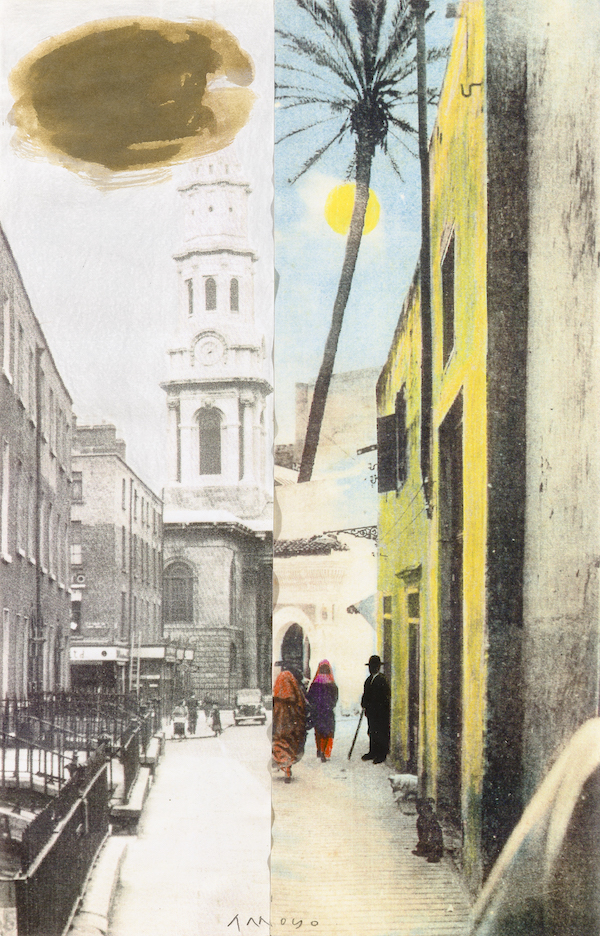

“Some of Arroyo’s black-and-white illustrations are printed in the margins of the book’s pages, while others are double-page paintings whose vivid colors are reminiscent of the Pop Art that inspired him.” His drawings, watercolors and collages include “eclectic images of shoes and hats, bulls and bats, as well as some sexually explicit representations of scenes that drew the wrath of censors a century ago.” For Ulysses’ “710 pages of inner monologue and dialogue, stream of consciousness, blank verse, Greek classics, and the venues and byways of Dublin, 1904,” as the Los Angeles Times‘ Jordan Riefe puts it, are as well known for their formidable complexity as it is for the power they once had to scandalize polite society.

Arroyo, who died in 2018, stayed faithful to Ulysses‘ content. (“Of course there are graphic nudes,” Riefe adds, “especially in later chapters.”) He also succeeded in completing an arduous project that the most notable artists of Joyce’s day refused even to attempt. “Joyce himself had asked Picasso and Matisse to illustrate it,” writes Galaxia Gutenberg’s Joan Tarrida, “but neither took on the task. Matisse preferred to illustrate The Odyssey,” Ulysses’ own structural inspiration, “which deeply offended Joyce.” What Joyce would make of Arroyo’s vital and multifarious illustrations, more of which you can sample at Literary Hub, is any scholar’s guess — but then, didn’t he say something about wanting to keep the scholars guessing for centuries? You can now purchase a copy of Ulysses: An Illustrated Edition. Related content: Henri Matisse Illustrates James Joyce’s Ulysses (1935) Read Ulysses Seen, A Graphic Novel Adaptation of James Joyce’s Classic Henri Matisse Illustrates Baudelaire’s Censored Poetry Collection, Les Fleurs du Mal Read the Original Serialized Edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1918) Every Word of Joyce’s Ulysses Printed on a Single Poster Why Should You Read James Joyce’s Ulysses?: A New TED-ED Animation Makes the Case Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. |

| << Previous Day |

2022/02/14 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |