[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, June 12th, 2024

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | How the 13th-Century Sufi Poet Rumi Became One of the World’s Most Popular Writers The Middle East is hardly the world’s most harmonious region, and it only gets more fractious if you add in South Asia and the Mediterranean. But there’s one thing on which many residents of that wide geographical span can agree: Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī. One might at first imagine that a thirteenth-century poet and mystical philosopher who wrote in Persian, with occasional forays into Turkish, Arabic, and Greek, would be a niche figure today, if known at all. In fact, Rumi, as he’s commonly known, is now one of the most popular writers in not just the Middle East but the world; English reinterpretations of his verse have even made him the best-selling poet in the United States. “The transformative moment in Rumi’s life came in 1244, when he met a wandering mystic known as Shams of Tabriz,” writes the BBC’s Jane Ciabattari. She quotes Brad Gooch, author of Rumi’s Secret: The Life of the Sufi Poet of Love, describing them as having an “electric friendship for three years,” after which Shams disappeared. “Rumi coped by writing poetry,” which includes 3,000 poems written for “Shams, the prophet Muhammad and God. He wrote 2,000 rubayat, four-line quatrains. He wrote in couplets a six-volume spiritual epic, The Masnavi.” He did all this work in service of what, in the animated TED-Ed lesson above, Stephanie Honchell Smith calls his ultimate goal: “the reunification of his soul with God through the experience of divine love.” How is such a love to be accessed? “Love resides not in learning, not in knowledge, not in pages in books,” Rumi declared. “Wherever the debates of men may lead, that is not the lover’s path.” He pursued it through devotion to Shams’ Sufism, “participating in ritualized dancing and preaching the religion of love through lectures, poetry, and prose.” Later in life, he shifted “from ecstatic expressions of divine love to verses that guide others to discover it for themselves,” incorporating “ideas, stories, and quotes from Islamic religious texts, Arabic and Persian literature and earlier Sufi writings and poetry.” Perhaps there can be no full appreciation of Rumi’s work without a scholar’s understanding of the languages and cultures he knew. But if his sales figures are anything to go by, the longing into which his complex work taps is universal. Related content: The Mystical Poetry of Rumi Read By Tilda Swinton, Madonna, Robert Bly & Coleman Barks The Complex Geometry of Islamic Art & Design: A Short Introduction 500+ Beautiful Manuscripts from the Islamic World Now Digitized & Free to Download The Birth and Rapid Rise of Islam, Animated (622‑1453) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. |

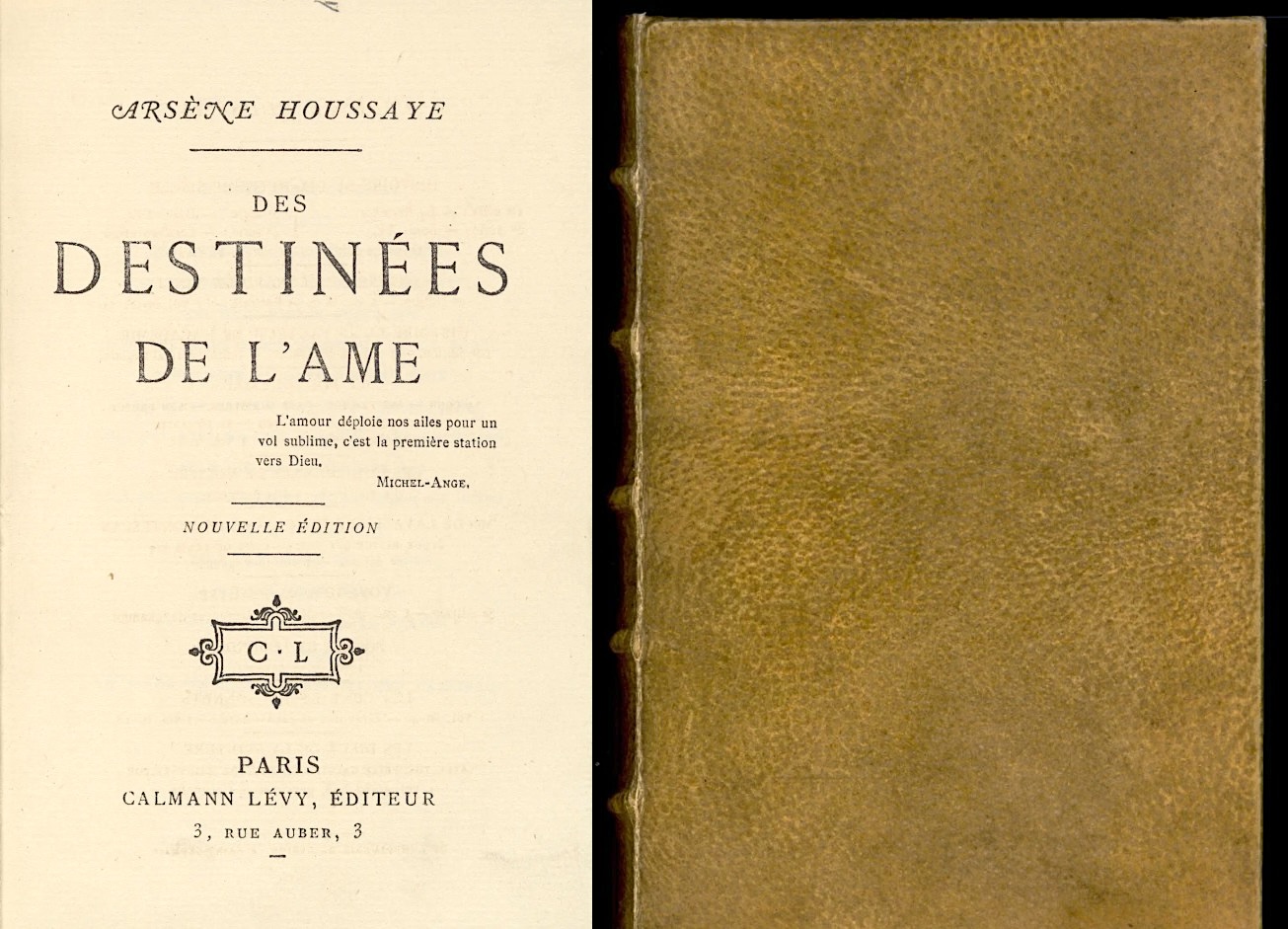

| 9:00a | Harvard Removes the Human Skin Binding from a Book in Its Collection Since 1934

In June of 2014, Harvard University’s Houghton Library put up a blog post titled “Caveat Lecter,” announcing “good news for fans of anthropodermic bibliopegy, bibliomaniacs, and cannibals alike.” The occasion was the scientific determination that a book in the Houghton’s collection long rumored to have been bound in human skin — the task of whose retrieval once served, they say, as a hazing ritual for student employees — was, indeed, “without a doubt bound in human skin.” What a difference a decade makes: not only has the blog post been deleted, the book itself has been taken out of from circulation in order to have the now-offending binding removed. “Harvard Library has removed human skin from the binding of a copy of Arsène Houssaye’s book Des destinées de l’âme (1880s),” declares a strenuously apologetic statement issued by the university. “The volume’s first owner, French physician and bibliophile Dr. Ludovic Bouland (1839–1933), bound the book with skin he took without consent from the body of a deceased female patient in a hospital where he worked.” Having been in the collection since 1934, the book was first placed there by John B. Stetson, Jr., “an American diplomat, businessman, and Harvard alumnus” (not to mention an heir to the fortune generated by the eponymous hat). “Bouland knew that Houssaye had written the book while grieving his wife’s death,” writes Mike Jay in the New York Review of Books, “and felt that this was an appropriate binding for it — ‘a book on the human soul merits that it be given human clothing.’ ” He also “included a note stating that “this book is bound in human skin parchment on which no ornament has been stamped to preserve its elegance.” This copy of Des destinées de l’âme isn’t the only book rumored — or, with the peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF) technology developed over the past decade, confirmed — to have been bound in human skin. “The oldest reputed examples are three 13th-century Bibles held at the Bibliothèque Nationale in France, write the New York Times’ Jennifer Schuessler and Julia Jacobs. Jay also mentions the especially vivid example of “an 1892 French edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Gold Bug, adorned with a skull emblem, is genuine human skin: Poe en peau humaine.” In general, Schuessler and Jacobs note, the largest number of human skin-bound books “date from the Victorian era, the heyday of anatomical collecting, when doctors sometimes had medical treatises and other texts bound in skin from patients or cadavers.” Now that this practice has been retroactively judged to be not just deeply disturbing but officially problematic (to use the vogue term of recent years) it’s up to the anthropodermic-bibliopegy enthusiasts out there to determine whether to put the items in their own collections to the PMF test — or to leave a bit of macabre mystery in the world of antiquarian book-collecting. Related content: Old Books Bound in Human Skin Found in Harvard Libraries (and Elsewhere in Boston) When Medieval Manuscripts Were Recycled & Used to Make the First Printed Books Behold the Codex Gigas (aka “Devil’s Bible”), the Largest Medieval Manuscript in the World A Mesmerizing Look at the Making of a Late Medieval Book from Start to Finish Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. |

| << Previous Day |

2024/06/12 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |