[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, June 25th, 2024

| Time | Event |

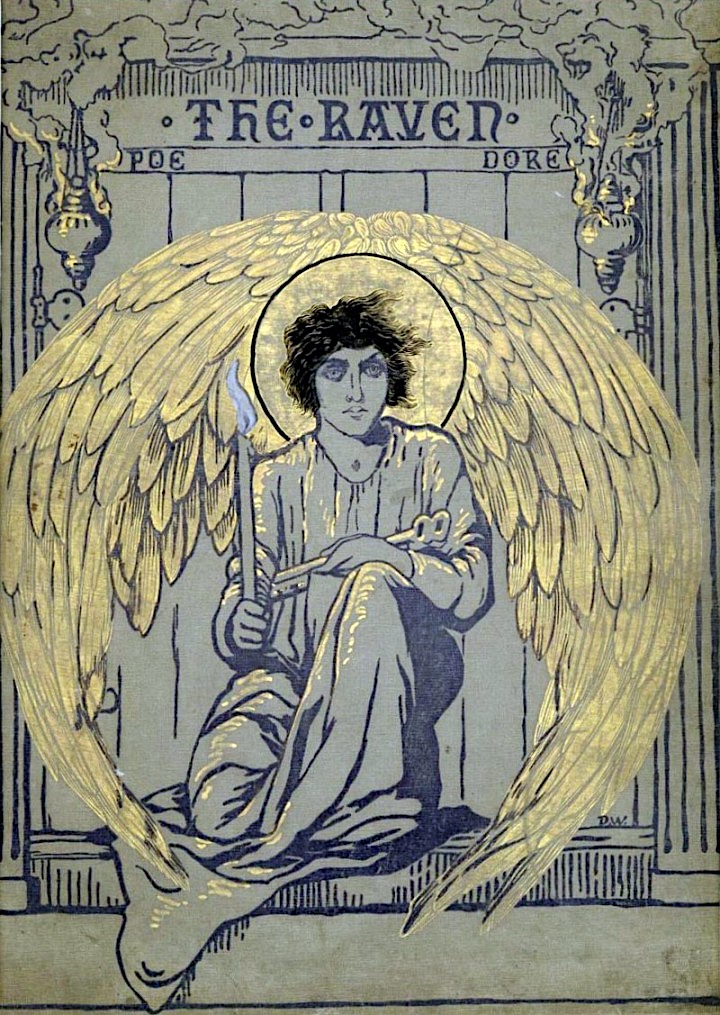

| 5:55a | Gustave Doré’s Macabre Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” (1884)

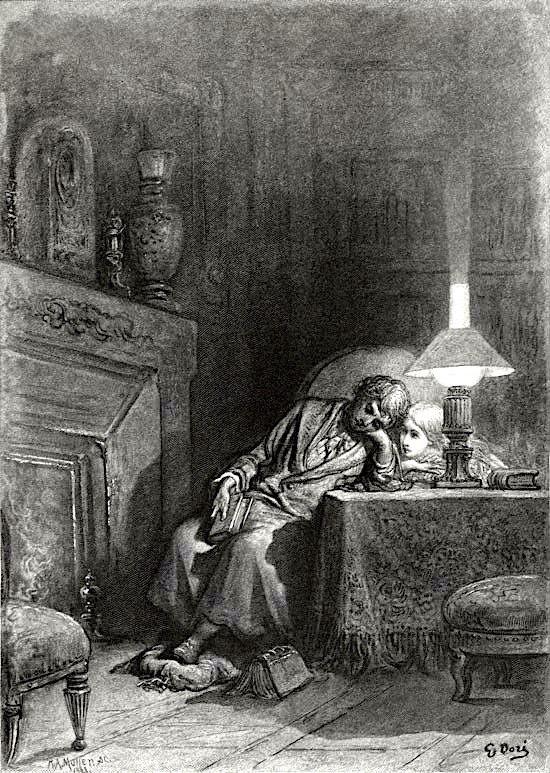

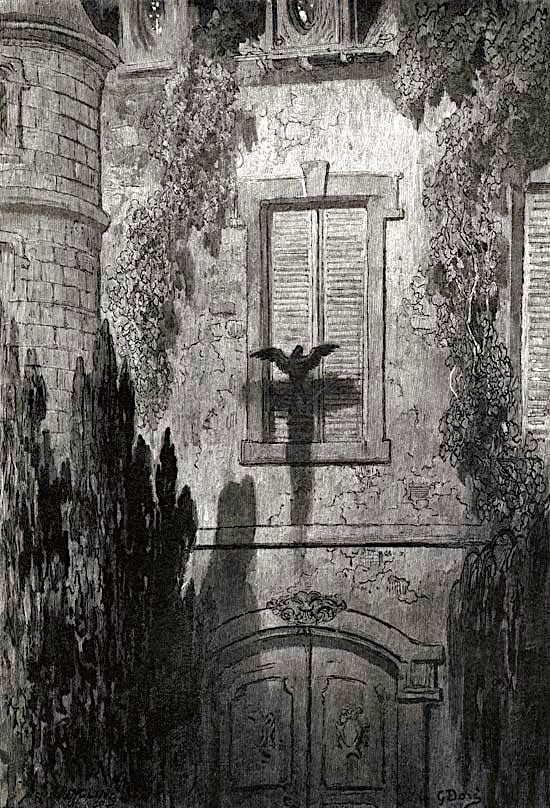

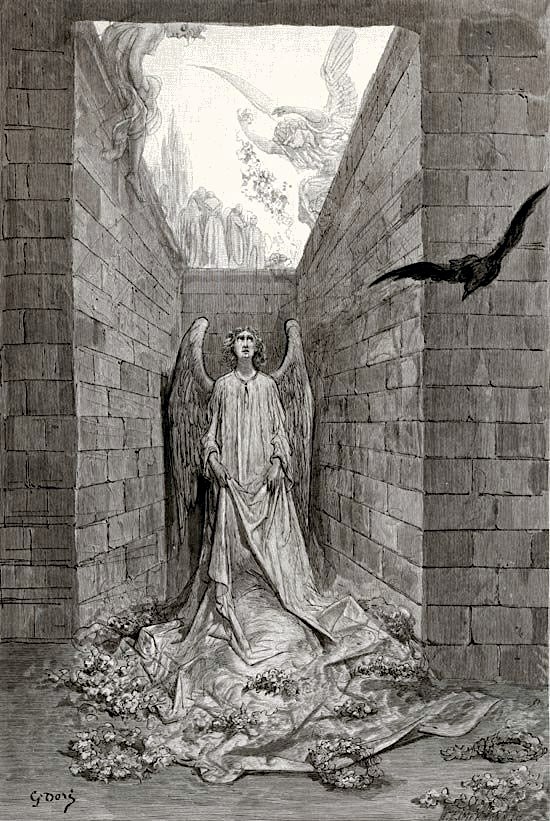

In 1884, he produced 26 steel engravings for an illustrated edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s gloomy classic “The Raven.” Like all of his illustrations, the images are rich with detail, yet in contrast to his earlier work, particularly the fine lines of his Quixote, these engravings are softer, characterized by a deep chiaroscuro appropriate to the mood of the poem.

Above see the plate depicting the first lines of the poem, the haunted speaker, “weak and weary,” slumped over one of his many “quaint and curious volume[s] of forgotten lore.” Below, see the raven tapping, “louder than before,” at the window lattice.

By the time Doré’s edition saw publication, Poe’s most famous work had already achieved recognition as one of the greatest of American poems. Its author, however, had died over thirty years previous in near-poverty. A catalog description from a Penn State Library holding of one of Doré’s “Raven” editions compares the two artists: The careers of these two men are fraught with both popular success and unmitigated disappointment. Doré enjoyed phenomenal monetary success as an illustrator in his life-time, however his true desire, to be acknowledged as a fine artist, was never realized. The critics of his day derided his abilities as an artist even as his popularity soared. One might say that Poe suffered the opposite fate—recognized as a great artist in his lifetime, he never achieved financial stability. We learn from the Penn State Rare Collections library that Doré received the rough equivalent of $140,000 for his illustrated edition of “The Raven.” Poe, on the other hand, was paid approximately nine dollars for his most famous poem.

The Library of Congress has digital editions of the complete Doré edition of “The Raven.”

Related Content: Gustave Doré’s Dramatic Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy The Adventures of Famed Illustrator Gustave Doré Presented in a Fantasic(al) Cutout Animation Gustave Doré’s Exquisite Engravings of Cervantes’ Don Quixote Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness |

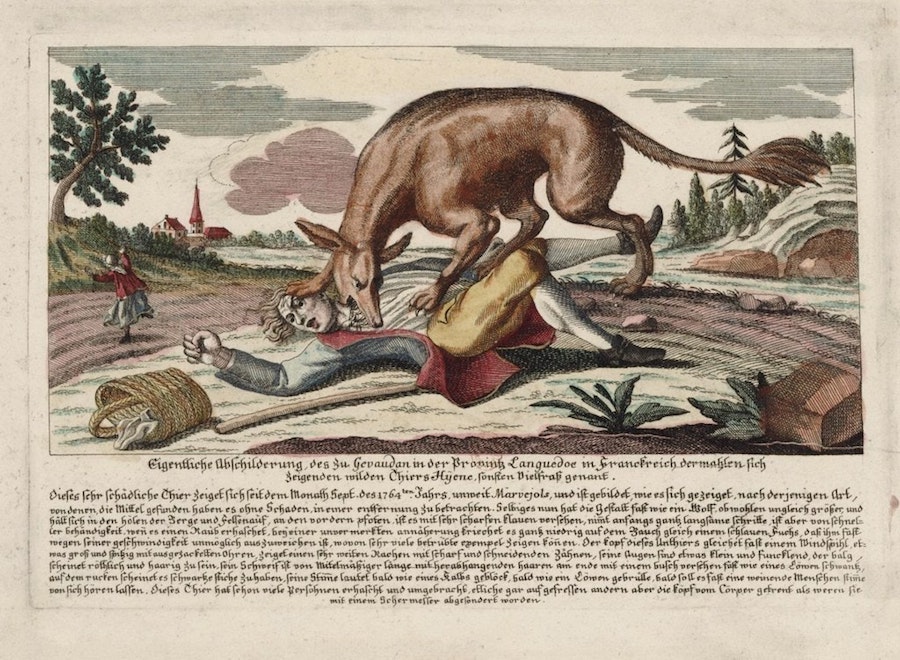

| 9:00a | How the 18th-Century French Media Stoked a Werewolf Panic

“In the 1760s, nearly three hundred people were killed in a remote region of south-central France called the Gévaudan (today part of the département of Lozère),” says the Public Domain Review. “The killer was thought to be a huge animal, which came to be known simply as ‘the Beast’; but while the creature’s name remained simple, its reputation soon grew extremely complex.” In the press, which speculated on this fearsome creature’s preferred methods of attack (decapitation, blood-drinking, etc.), “illustrators had a field day representing the Beast, whose appearance was reported to be so monstrous it beggared belief.”

By the winter of 1764–65, “the attacks in the Gévaudan had created a national fervor, to the point that King Louis XV intervened, offering a reward equal to what most men would have earned in a year.” In September of 1756, a lieutenant named François Antoine “shot the enormous ‘Wolf of Chazes,’ which was stuffed and put on display in Versailles.” This didn’t stop the killings, but “by now the Royal Court had lost interest. The story had played itself out, and public attention had moved on to other matters. Luckily a local nobleman, the Marquis d’Apcher, organized another hunt, and in June 1767 the hunter Jean Chastel laid low the last of what had turned out to be the Beasts of the Gévaudan.”

“The Beast’s stomach was filled with human remains and, by all posthumous accounts, did not look anything like a typical wolf,” says Dangerous Minds. “They were also able to ascertain that the animal was solely responsible for 95% of the attacks on humans from 1764 to 1767.” As to what the animal actually was, theories abound: maybe an unusually large or rabid wolf, maybe a hyena, maybe even a lion. As for the more fantastical theories that captured the public imagination of the time, they may have passed into the realm of myth, but those myths continue to inspire literature, film, television, and games. And as anyone who’s played Les Loups-garous de Thiercelieux a few times understands, the werewolf’s luck usually runs out. Related content: The Sights & Sounds of 18th Century Paris Get Recreated with 3D Audio and Animation A 1665 Advertisement Promises a “Famous and Effectual” Cure for the Great Plague How the Year 2440 Was Imagined in a 1771 French Sci-Fi Novel Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. |

| << Previous Day |

2024/06/25 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |