[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, August 6th, 2024

| Time | Event |

| 5:53a | Mark Twain & Helen Keller’s Special Friendship: He Treated Me Not as a Freak, But as a Person Dealing with Great Difficulties

Sometimes it can seem as though the more we think we know a historical figure, the less we actually do. Helen Keller? We’ve all seen (or think we’ve seen) some version of The Miracle Worker, right?—even if we haven’t actually read Keller’s autobiography. And Mark Twain? He can seem like an old family friend. But I find people are often surprised to learn that Keller was a radical socialist firebrand, in sympathy with workers’ movements worldwide. In a short article in praise of Lenin, for example, Keller once wrote, “I cry out against people who uphold the empire of gold…. I am perfectly sure that love will bring everything right in the end, but I cannot help sympathizing with the oppressed who feel driven to use force to gain the rights that belong to them.” Twain took a more pessimistic, ironic approach, yet he thoroughly opposed religious dogma, slavery, and imperialism. “I am always on the side of the revolutionists,” he wrote, “because there never was a revolution unless there were some oppressive and intolerable conditions against which to revolute.” While a great many people grow more conservative with age, Twain and Keller both grew more radical, which in part accounts for another little-known fact about these two nineteenth-century American celebrities: they formed a very close and lasting friendship that, at least in Keller’s case, may have been one of the most important relationships in either figure’s lives.

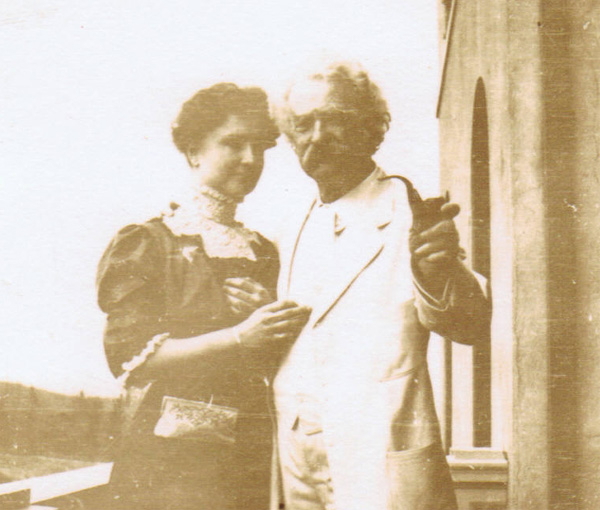

Twain’s importance to Keller, and hers to him, begins in 1895, when the two met at a lunch held for Keller in New York. According to the Mark Twain Library’s extensive documentary exhibit, Keller “seemed to feel more at ease with Twain than with any of the other guests.” She would later write, “He treated me not as a freak, but as a handicapped woman seeking a way to circumvent extraordinary difficulties.” Twain was taken as well, surprised by “her quickness and intelligence.” After the meeting, he wrote to his benefactor Henry H. Rogers, asking Rogers to fund Keller’s education. Rogers, the Mark Twain Library tells us, “personally took charge of Helen Keller’s fortunes, and out of his own means made it possible for her to continue her education and to achieve for herself the enduring fame which Mark Twain had foreseen.” Twain wrote to his wealthy friend, “It won’t do for America to allow this marvelous child to retire from her studies because of poverty. If she can go on with them she will make a fame that will endure in history for centuries.” Thereafter, the two would maintain a “special friendship,” sustained not only by their political sentiments, but also by a love of animals, travel, and other personal similarities. Both writers came to live in Fairfield County, Connecticut at the end of their lives, and she visited him at his Redding home, Stormfield, in 1909, the year before his death (see them there at the top of the post, and more photos here). Twain was especially impressed by Keller’s autobiography, writing to her, “I am charmed with your book—enchanted.” (See his endorsement in a 1903 advertisement, below.)

Twain also came to Keller’s defense, ten years later, after reading in her book about a plagiarism scandal that occurred in 1892 when, at only twelve years old, she was accused of lifting her short story “The Frost King” from Margaret Canby’s “Frost Fairies.” Though a tribunal acquitted Keller of the charges, the incident still piqued Twain, who called it “unspeakably funny and owlishly idiotic and grotesque” in a 1903 letter in which he also declared: “The kernel, the soul—let us go further and say the substance, the bulk, the actual and valuable material of all human utterance—is plagiarism.” What differs from work to work, he contends is “the phrasing of a story”; Keller’s accusers, he writes protectively, were “solemn donkeys breaking a little child’s heart.”

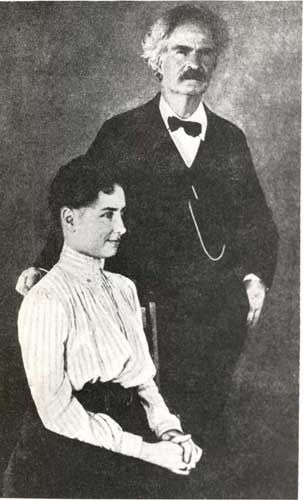

We also have Twain—not playwright William Gibson—to thank for the “miracle worker” title given to Keller’s teacher, Anne Sullivan. (See Keller, Sullivan, Twain, and Sullivan’s husband John Macy above at Twain’s home). As a tribute to Sullivan for her tireless work with Keller, he presented her with a postcard that read, “To Mrs. John Sullivan Macy with warm regard & with limitless admiration of the wonders she has performed as a ‘miracle-worker.’” In his 1903 letter to Keller, he called Sullivan “your other half… for it took the pair of you to make complete and perfect whole.” Twain praised Sullivan effusively for “her brilliancy, penetration, originality, wisdom, character, and the fine literary competencies of her pen.” But he reserved his highest praise for Keller herself. “You are a wonderful creature,” he wrote, “The most wonderful in the world.” Keller’s praise of her friend Twain was no less lofty. “I have been in Eden three days and I saw a King,” she wrote in his guestbook during her visit to Stormfield, “I knew he was a King the minute I touched him though I had never touched a King before.” The last words in Twain’s autobiography, the first volume anyway—which he only allowed to be published in 2010—are Keller’s; “You once told me you were a pessimist, Mr. Clemons,” he quotes her as saying, “but great men are usually mistaken about themselves. You are an optimist.” Related Content: Helen Keller Had Impeccable Handwriting: See a Collection of Her Childhood Letters Helen Keller Speaks About Her Greatest Regret — Never Mastering Speech Helen Keller & Annie Sullivan Appear Together in Moving 1930 Newsreel Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

|

| 9:00a | An Introduction to The Babylonian Map of the World–the Oldest Known Map of the World Taking a first glance at the Babylonian Map of the World, few of us could recognize it for what it is. But then again, few of us are anything like the British Museum Middle East department curator Irving Finkel, whose vast knowledge (and ability to share it compellingly) have made him a viewer favorite on the institution’s Youtube channel. In the Curator’s Corner video above, he offers an up-close view of the Babylonian Map of the World — or rather, the fragment of the clay tablet from the eighth or seventh century BC that he and other experts have determined contains a piece of the oldest map of the known world in existence. “If you look carefully, you will see that the flat surface of the clay has a double circle,” Finkel says. Within the circle is cuneiform writing that describes the shape as the “bitter river” that surrounds the known world: ancient Mesopotamia, or modern-day Iraq. Inside the circle lie representations of both the Euphrates River and the mighty city of Babylon; outside it lie a series of what scholars have determined were originally eight triangles. “Sometimes people say they are islands, sometimes people say they are districts, but in point of fact, they are almost certainly mountains,” which stand “far beyond the known world” and represent, to the ancient Babylonians, “places full of magic, and full of mystery.” Coming up with a coherent explanation of the map itself hinged on the discovery, in the nineteen-nineties, of one of those triangles originally thought to have been lost. This owes to the enthusiasm of a non-professional, a student in Finkel’s cuneiform night classes named Edith Horsley. During one of her once-a-week volunteer shifts at the British Museum, she set aside a particularly intriguing clay fragment. As soon as Finkel saw it, he knew just the artifact to which it belonged. After the piece’s reattachment, much fell into place, not least that the map purported to show the distant location of the beached (or rather, mountained) ark built by “the Babylonian version of Noah” — the search for which continues these nine or so millennia later. Related content: The World Map That Introduced Scientific Mapmaking to the Medieval Islamic World (1154 AD) How Did Cartographers Create World Maps before Airplanes and Satellites? An Introduction Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. |

| << Previous Day |

2024/08/06 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |