[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, August 14th, 2024

| Time | Event |

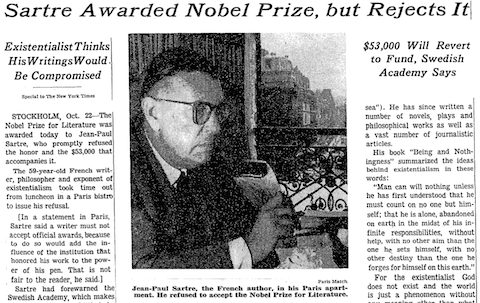

| 7:54a | Jean-Paul Sartre Rejects the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964: “It Was Monstrous!” In a 2013 blog post, the great Ursula K. Le Guin quotes a London Times Literary Supplement column by a “J.C.,” who satirically proposes the “Jean-Paul Sartre Prize for Prize Refusal.” “Writers all over Europe and America are turning down awards in the hope of being nominated for a Sartre,” writes J.C., “The Sartre Prize itself has never been refused.” Sartre earned the honor of his own prize for prize refusal by turning down the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964, an act Le Guin calls “characteristic of the gnarly and counter-suggestible Existentialist.” As you can see in the short clip above, Sartre fully believed the committee used the award to whitewash his Communist political views and activism. But the refusal was not a theatrical or “impulsive gesture,” Sartre wrote in a statement to the Swedish press, which was later published in Le Monde. It was consistent with his longstanding principles. “I have always declined official honors,” he said, and referred to his rejection of the Legion of Honor in 1945 for similar reasons. Elaborating, he cited first the “personal” reason for his refusal

There was another reason as well, an “objective” one, Sartre wrote. In serving the cause of socialism, he hoped to bring about “the peaceful coexistence of the two cultures, that of the East and the West.” (He refers not only to Asia as “the East,” but also to “the Eastern bloc.”) Therefore, he felt he must remain independent of institutions on either side: “I should thus be quite as unable to accept, for example, the Lenin Prize, if someone wanted to give it to me.”

As a flattering New York Times article noted at the time, this was not the first time a writer had refused the Nobel. In 1926, George Bernard Shaw turned down the prize money, offended by the extravagant cash award, which he felt was unnecessary since he already had “sufficient money for my needs.” Shaw later relented, donating the money for English translations of Swedish literature. Boris Pasternak also refused the award, in 1958, but this was under extreme duress. “If he’d tried to go accept it,” Le Guin writes, “the Soviet Government would have promptly, enthusiastically arrested him and sent him to eternal silence in a gulag in Siberia.” These qualifications make Sartre the only author to ever outright and voluntarily reject both the Nobel Prize in Literature and its sizable cash award. While his statement to the Swedish press is filled with polite explanations and gracious demurrals, his filmed statement above, excerpted from the 1976 documentary Sartre by Himself, minces no words.

Sartre was in fact pardoned by De Gaulle four years after his Nobel rejection for his participation in the 1968 uprisings. “You don’t arrest Voltaire,” the French President supposedly said. The writer and philosopher, Le Guin points out, “was, of course, already an ‘institution’” at the time of the Nobel award. Nonetheless, she says, the gesture had real meaning. Literary awards, writes Le Guin—who herself refused a Nebula Award in 1976 (she’s won several more since)—can “honor a writer,” in which case they have “genuine value.” Yet prizes are also awarded “as a marketing ploy by corporate capitalism, and sometimes as a political gimmick by the awarders [….] And the more prestigious and valued the prize the more compromised it is.” Sartre, of course, felt the same—the greater the honor, the more likely his work would be coopted and sanitized. Perhaps proving his point, a short, nasty 1965 Harvard Crimson letter had many, less flattering things than Le Guin to say about Sartre’s motivations, calling him “an ugly toad” and a “poor loser” envious of his former friend Camus, who won in 1957. The letter writer calls Sartre’s rejection of the prize “an act of pretension” and a “rather ineffectual and stupid gesture.” And yet it did have an effect. It seems clear at least to me that the Harvard Crimson writer could not stand the fact that, offered the “most coveted award” the West can bestow, and a heaping sum of money besides, “Sartre’s big line was, ‘Je refuse.’” Related Content: Jean-Paul Sartre & Albert Camus: Their Friendship and the Bitter Feud That Ended It Hear Albert Camus Deliver His Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech (1957) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness |

| 9:00a | J. G. Ballard Demystifies Surrealist Paintings by Dalí, Magritte, de Chirico & More

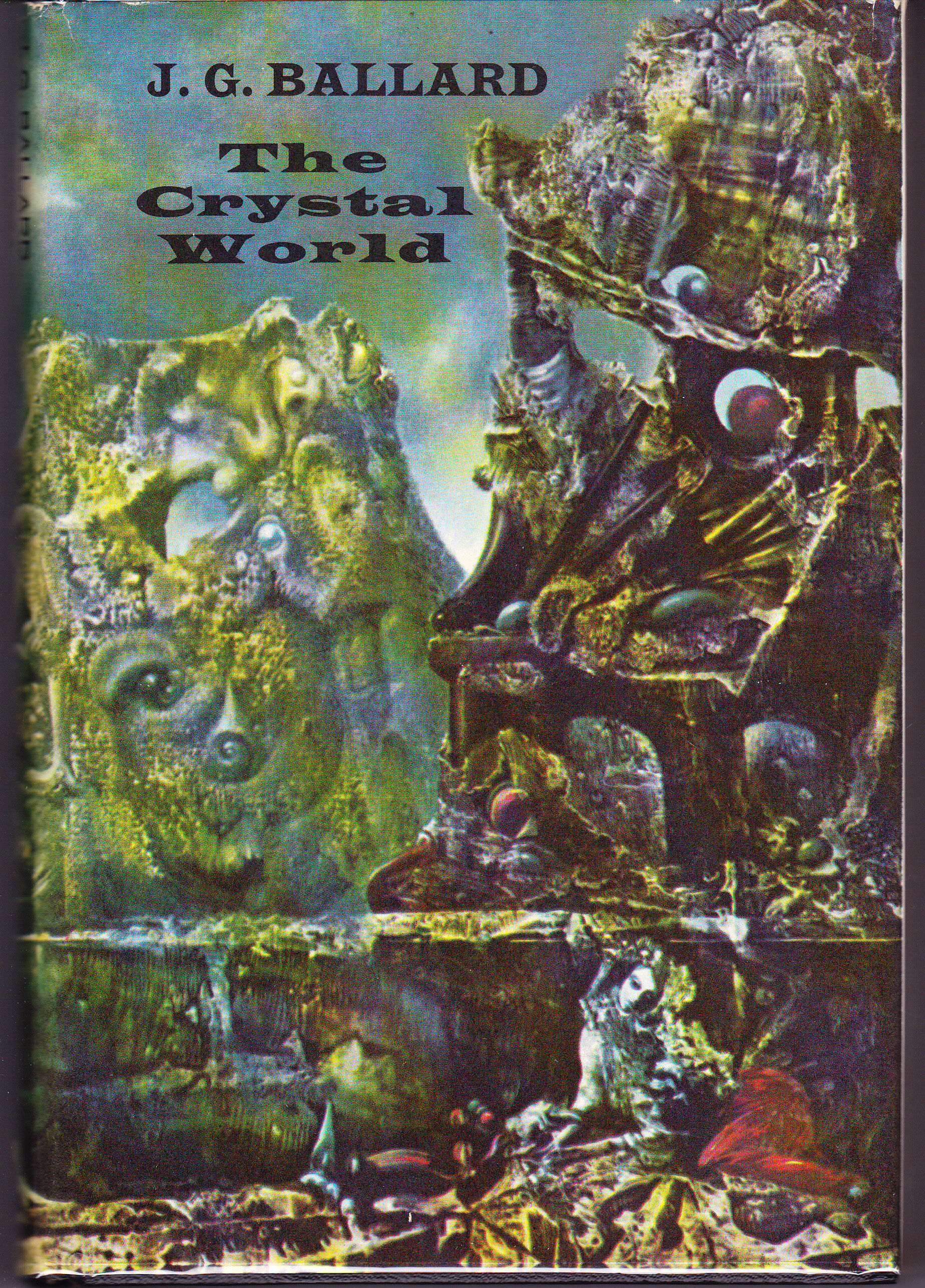

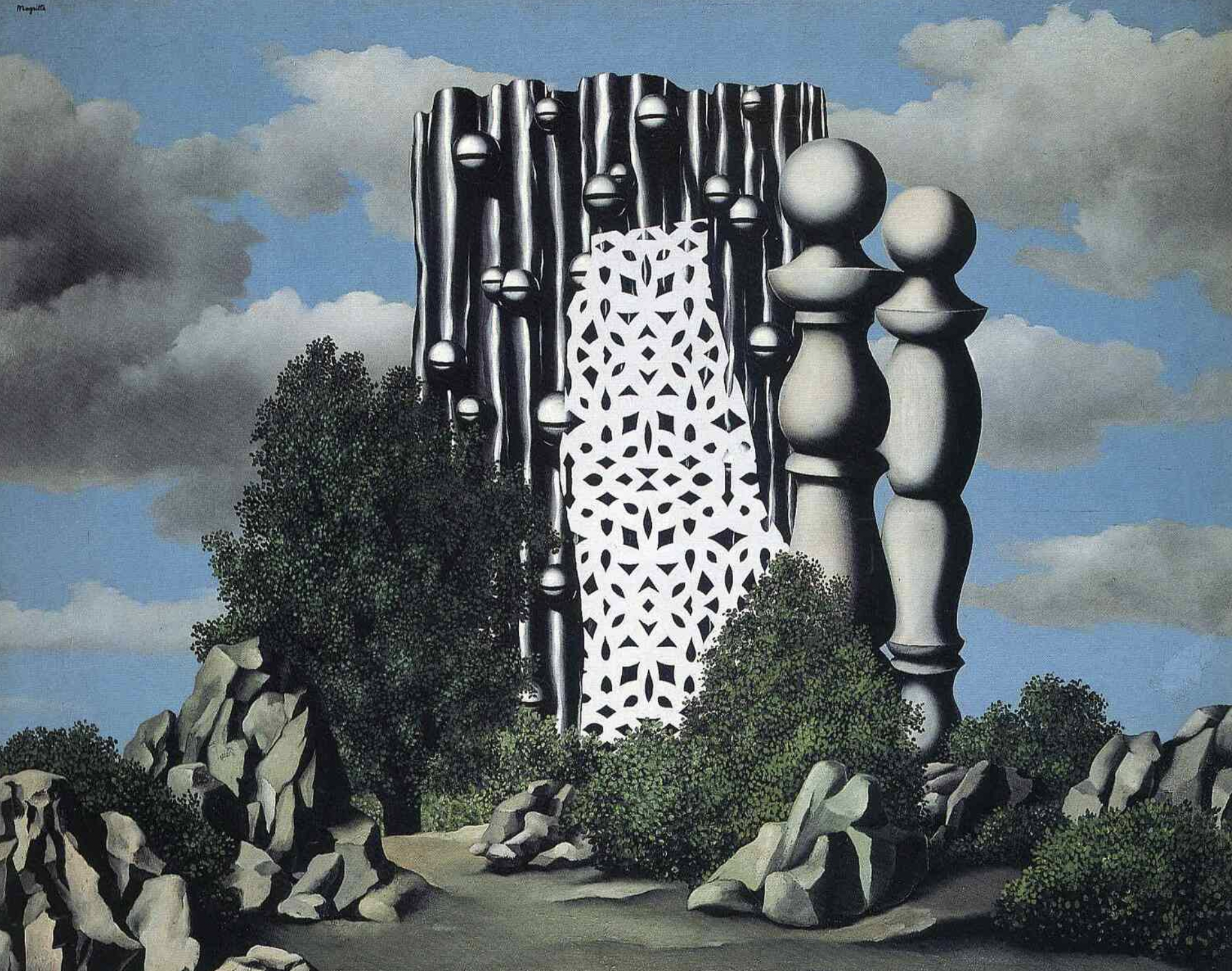

Before his signature works like The Atrocity Exhibition, Crash, and High-Rise, J. G. Ballard published three apocalyptic novels, The Drowned World, The Burning World, and The Crystal World. Each of those books offers a different vision of large-scale environmental disaster, and the last even provides a clue as to its inspiration. Or rather, its original cover does, by using a section of Max Ernst’s painting The Eye of Silence. “This spinal landscape, with its frenzied rocks towering into the air above the silent swamp, has attained an organic life more real than that of the solitary nymph sitting in the foreground,” Ballard writes in “The Coming of the Unconscious,” an article on surrealism written shortly after The Crystal World appeared in 1966. First published in an issue of the magazine New Worlds (which also contains Ballard’s take on Chris Marker’s La Jetée), the piece is ostensibly a review of Patrick Waldberg’s Surrealism and Marcel Jean’s The History of Surrealist Painting, but it ends up delivering Ballard’s short analyses of a series of paintings by various surrealist masters. The Eye of Silence shows the landscapes of our world “for what they are — the palaces of flesh and bone that are the living facades enclosing our own subliminal consciousness.” The “terrifying structure” at the center of René Magritte’s The Annunciation is “a neuronic totem, its rounded and connected forms are a fragment of our own nervous systems, perhaps an insoluble code that contains the operating formulae for our own passage through time and space.”

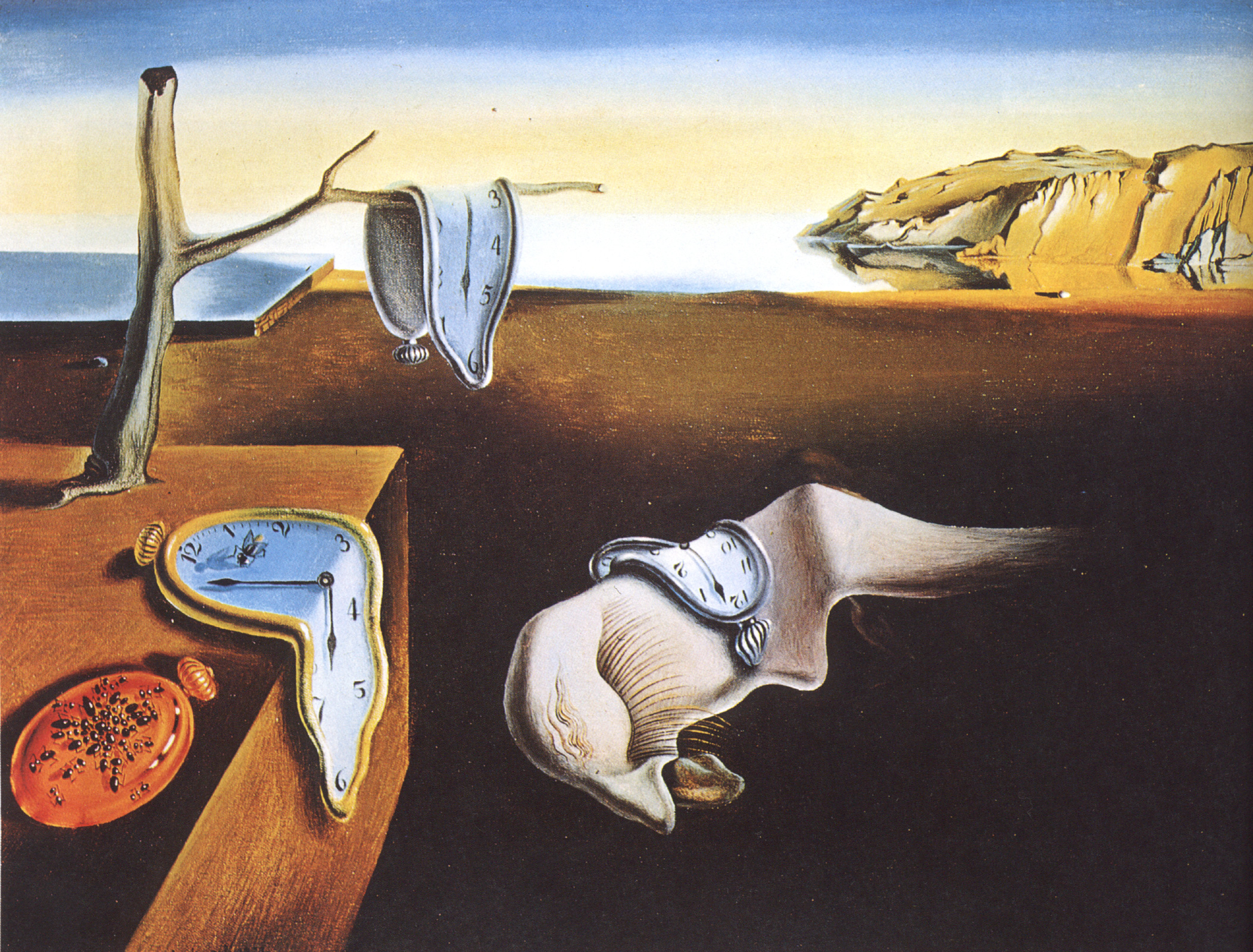

In Giorgio de Chirico’s The Disquieting Muses, “an undefined anxiety has begun to spread across the deserted square. The symmetry and regularity of the arcades conceals an intense inner violence; this is the face of catatonic withdrawal”; its figures are “human beings from whom all transitional time has been eroded.” Another work depicts an empty beach as “a symbol of utter psychic alienation, of a final stasis of the soul”; its displacement of beach and sea through time “and their marriage with our own four-dimensional continuum, has warped them into the rigid and unyielding structures of our own consciousness.” There Ballard writes of no less familiar a canvas than The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dalí, whom he called “the greatest painter of the twentieth century” more than 40 years after “The Coming of the Unconscious” in the Guardian.

A decade thereafter, that same publication’s Declan Lloyd theorizes that the experimental billboards designed by Ballard in the fifties (previously featured here on Open Culture) had been textual reinterpretations of Dalí’s imagery. Until the late sixties, Ballard says in a 1995 World Art interview, “the Surrealists were very much looked down upon. This was part of their attraction to me, because I certainly didn’t trust English critics, and anything they didn’t like seemed to me probably on the right track. I’m glad to say that my judgment has been seen to be right — and theirs wrong.” He understood the long-term value of Surrealist visions, which had seemingly been obsolesced by World War II before, “all too soon, a new set of nightmares emerged.” We can only hope he won’t be proven as prescient about the long-term habitability of the planet. Related content: Sci-Fi Author J.G. Ballard Predicts the Rise of Social Media (1977) J. G. Ballard’s Experimental Text Collages: His 1958 Foray into Avant-Garde Literature An Introduction to Surrealism: The Big Aesthetic Ideas Presented in Three Videos Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. |

| << Previous Day |

2024/08/14 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |