[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, September 26th, 2024

| Time | Event |

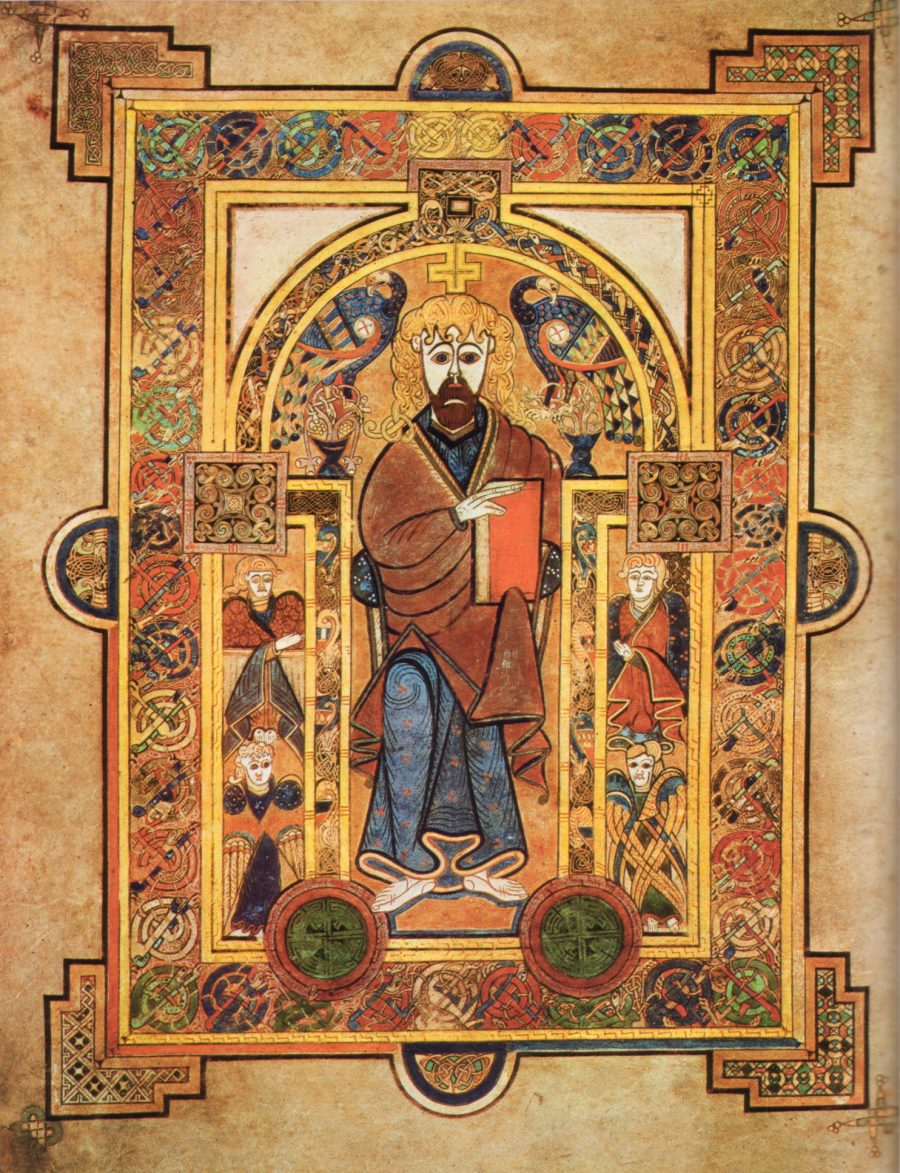

| 5:27a | The Medieval Masterpiece, the Book of Kells, Is Now Digitized and Available Online

If you know nothing else about medieval European illuminated manuscripts, you surely know the Book of Kells. “One of Ireland’s greatest cultural treasures” comments Medievalists.net, “it is set apart from other manuscripts of the same period by the quality of its artwork and the sheer number of illustrations that run throughout the 680 pages of the book.” The work not only attracts scholars, but almost a million visitors to Dublin every year. “You simply can’t travel to the capital of Ireland,” writes Book Riot’s Erika Harlitz-Kern, “without the Book of Kells being mentioned. And rightfully so.” The ancient masterpiece is a stunning example of Hiberno-Saxon style, thought to have been composed on the Scottish island of Iona in 806, then transferred to the monastery of Kells in County Meath after a Viking raid (a story told in the marvelous animated film The Secret of Kells). Consisting mainly of copies of the four gospels, as well as indexes called “canon tables,” the manuscript is believed to have been made primarily for display, not reading aloud, which is why “the images are elaborate and detailed while the text is carelessly copied with entire words missing or long passages being repeated.” Its exquisite illuminations mark it as a ceremonial object, and its “intricacies,” argue Trinity College Dublin professors Rachel Moss and Fáinche Ryan, “lead the mind along pathways of the imagination…. You haven’t been to Ireland unless you’ve seen the Book of Kells.” This may be so, but thankfully, in our digital age, you need not go to Dublin to see this fabulous historical artifact, or a digitization of it at least, entirely viewable at the online collections of the Trinity College Library. (When you click on the previous link, make sure you scroll down the page.) The pages, originally captured in 1990, “have recently been rescanned,” Trinity College Library writes, using state-of-the-art imaging technology. These new digital images offer the most accurate high-resolution images to date, providing an experience second only to viewing the book in person.” What makes the Book of Kells so special, reproduced “in such varied places as Irish national coinage and tattoos?” asks Professors Moss and Ryan. “There is no one answer to these questions.” In their free online course on the manuscript, these two scholars of art history and theology, respectively, do not attempt to “provide definitive answers to the many questions that surround it.” Instead, they illuminate its history and many meanings to different communities of people, including, of course, the people of Ireland. “For Irish people,” they explain in the course trailer above, “it represents a sense of pride, a tangible link to a positive time in Ireland’s past, reflected through its unique art.” But while the Book of Kells is still a modern “symbol of Irishness,” it was made with materials and techniques that fell out of use several hundred years ago, and that were once spread far and wide across Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. In the video above, Trinity College Library conservator John Gillis shows us how the manuscript was made using methods that date back to the “development of the codex, or the book form.” This includes the use of parchment, in this case calf skin, a material that remembers the anatomical features of the animals from which it came, with markings where tails, spines, and legs used to be. The Book of Kells has weathered the centuries fairly well, thanks to careful preservation, but it’s also had perhaps five rebindings in its lifetime. “In its original form,” notes Harlitz-Kern, the manuscript “was both thicker and larger. Thirty folios of the original manuscript have been lost through the centuries and the edges of the existing manuscript were severely trimmed during a rebinding in the nineteenth century.” It remains, nonetheless, one of the most impressive artifacts to come from the age of the illuminated manuscript, “described by some,” says Moss and Ryan, “as the most famous manuscript in the world.” Find out why by seeing it (virtually) for yourself and learning about it from the experts above. For anyone interested in getting a copy of The Book of Kells in a nice print format, see The Book of Kells: Reproductions from the manuscript in Trinity College, Dublin. Related Content: Take a Free Online Course on the Great Medieval Manuscript, the Book of Kells Killer Rabbits in Medieval Manuscripts: Why So Many Drawings in the Margins Depict Bunnies Going Bad Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness |

| 9:00a | How Filmmakers Make Cameras Disappear: Mirrors in Movies If you’ve never tried your hand at filmmaking, you might assume that its hardest visual challenges are the creation of effects-laden spectacles: starships duking it out in space, monsters stomping through major cities, animals speaking and dancing like Broadway stars, that sort of thing. But consider the challenge posed by simply capturing a scene set in a bathroom. Almost all such spaces include a large mirror, meaning that most angles from which you could shoot will violate an important rule cited by Youtuber Paul E.T. in the video above: “Don’t show the camera in the shot.” Yet we’ve all seen major motion pictures and television series with scenes not just in bathrooms but other mirror-equipped spaces, from rooms used for interrogating suspects to rooms used for preparing to come out on stage. What’s more, the camera often passes blithely before these mirrors with a vampire-like lack of a reflection. The techniques used to achieve such shots are now mature enough that we may not even notice that what we’re seeing doesn’t make visual sense. How they work is the subject of Paul E.T.‘s investigation, beginning with an episode of Criminal: United Kingdom in which a camera somehow floats around a room with a one-way mirror, never appearing in that mirror. Another more familiar example comes from Contact, directed by the visual-effects maven Robert Zemeckis. In its early flashback sequence, an adolescent version of its astronomer protagonist runs toward the backward-tracking camera and reaches out to open what turns out to be a bathroom medicine cabinet, into whose mirror we must have — yet cannot possibly have — been looking into the whole time. What we’re seeing is actually a seamless fusion of two shots, with the “empty” (that is, blue-screen-filled) frame of the cabinet mirror superimposed on the end of the shot of the young actress running toward it. While not technically easy, it’s at least conceptually straightforward. Paul E.T. finds another, more complicated mirror shot in no less a masterwork of cinema than Zack Snider’s Sucker Punch, which tracks all the way around from one side of a set of dressing-room mirrors to the other. “What you’re actually seeing when the camera moves is the transitioning from one side of a duplicated set to the other,” he explains, “with an invisible cut spliced in there” — which involves lookalike actresses literally trying to mirror each other’s movements. No such elaborate trickery for Ruben Östlund’s Force Majeure, which shoots straight-on into a bathroom mirror by building the camera into the wall, then digitally erasing it in post-production. While we do live in an age of “fix it in post” (an instinct with an arguably regrettable effect on cinema), mirror shots, on the whole, still require some degree of foresight and inventiveness. Such was the case with that scene from Criminal: United Kingdom, which Paul E.T. simply couldn’t figure out on his own. His search for answers led him to e‑mail the episode’s B‑camera operator, who explained that the production involved neither a blue screen nor doubles, but “a combination of well-choreographed camera work and VFX.” The result: a shot that may look unremarkable at first, but on closer inspection, attests to the subtle power of movie magic — or TV magic, at any rate. Related content: The Art of Creating Special Effects in Silent Movies: Ingenuity Before the Age of CGI This Is What The Matrix Looks Like Without CGI: A Special Effects Breakdown Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook. |

| << Previous Day |

2024/09/26 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |