[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, February 11th, 2025

| Time | Event |

| 9:00a | Tracing English Back to Its Oldest Known Ancestor: An Introduction to Proto-Indo-European People understand evolution in all sorts of different ways. We’ve all heard a variety of folk explanations of that all-important phenomenon, from “survival of the fittest” to “humans come from monkeys,” that run the spectrum from broadly correct to badly mangled. One less often heard but more elegant way to put it is that all species, living or extinct, share a common ancestor. This is true of evolution as Darwin knew it, and it could well be true of other forms of “evolution” outside the biological realm as well. Take languages, which we know full well have changed and split into different varieties over time: do they, too, all share a single ancestor? In the RobWords video above, language Youtuber Rob Watts starts with his native English and traces its roots back as far as possible. He ascends up the family tree past Low West German, past Proto-Germanic — “a language that was theoretically spoken by a single group of people who would eventually go on to become the Swedes, the Germans, the Dutch, the English, and more” — back to an ancestor of not just English and the Germanic languages, but almost all the European languages, as well as of Asian languages like Hindi, Pashtu, Kurdish, Farsi, and Bengali. Its name? Proto-Indo-European. Watts quotes the eighteenth-century philologist Sir William Jones, who wrote that the ancient Asian language of Sanskrit has a structure “more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident.” As with such conspicuously shared traits observed in disparate species of plant or animal, no expert “could examine all three without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists.” The evidence is everywhere, if you pay attention to the sort of unexpected cognates and very-nearly-cognates Watts points out spanning geographically and temporally various languages. Take the English hundred, the Latin centum, the Ancient Greek hekaton, the Russian sto, and the Sanskrit Shatam; or the more deeply buried resemblances of English heart, the Latin cordis, the Russian serdce, and the sanskrit hrd. In some cases, linguists have actually used these commonalities to reverse-engineer Proto-Indo-European words, though always with the caveat that the whole thing “is a reconstructed language; it’s our best guess of what a common ancestral language could have been like.” Was there a still older language from which the non-Proto-Indo-European-descended languages also descended? That’s a question to push the linguistic imagination to its very limits. Related content: Was There a First Human Language?: Theories from the Enlightenment Through Noam Chomsky How Languages Evolve: Explained in a Winning TED-Ed Animation The Alphabet Explained: The Origin of Every Letter The Tree of Languages Illustrated in a Big, Beautiful Infographic Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| 10:00a | Horrifying 1906 Illustrations of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds: Discover the Art of Henrique Alvim Corrêa

H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds has terrified and fascinated readers and writers for decades since its 1898 publication and has inspired numerous adaptations. The most notorious use of Wells’ book was by Orson Welles, whom the author called “my little namesake,” and whose 1938 War of the Worlds Halloween radio play caused public alarm (though not actually a national panic). After the occurrence, reports Phil Klass, the actor remarked, “I’m extremely surprised to learn that a story, which has become familiar to children through the medium of comic strips and many succeeding and adventure stories, should have had such an immediate and profound effect upon radio listeners.”

Surely Welles knew that is precisely why the broadcast had the effect it did, especially in such an anxious pre-war climate. The 1898 novel also startled its first readers with its verisimilitude, playing on a late Victorian sense of apocalyptic doom as the turn-of-the century approached. But what contemporary circumstances eight years later, we might wonder, fueled the imagination of Henrique Alvim Corrêa, whose 1906 illustrations of the novel you can see here? Wells himself approved of these incredible drawings, praising them before their publication and saying, “Alvim Corrêa did more for my work with his brush than I with my pen.”

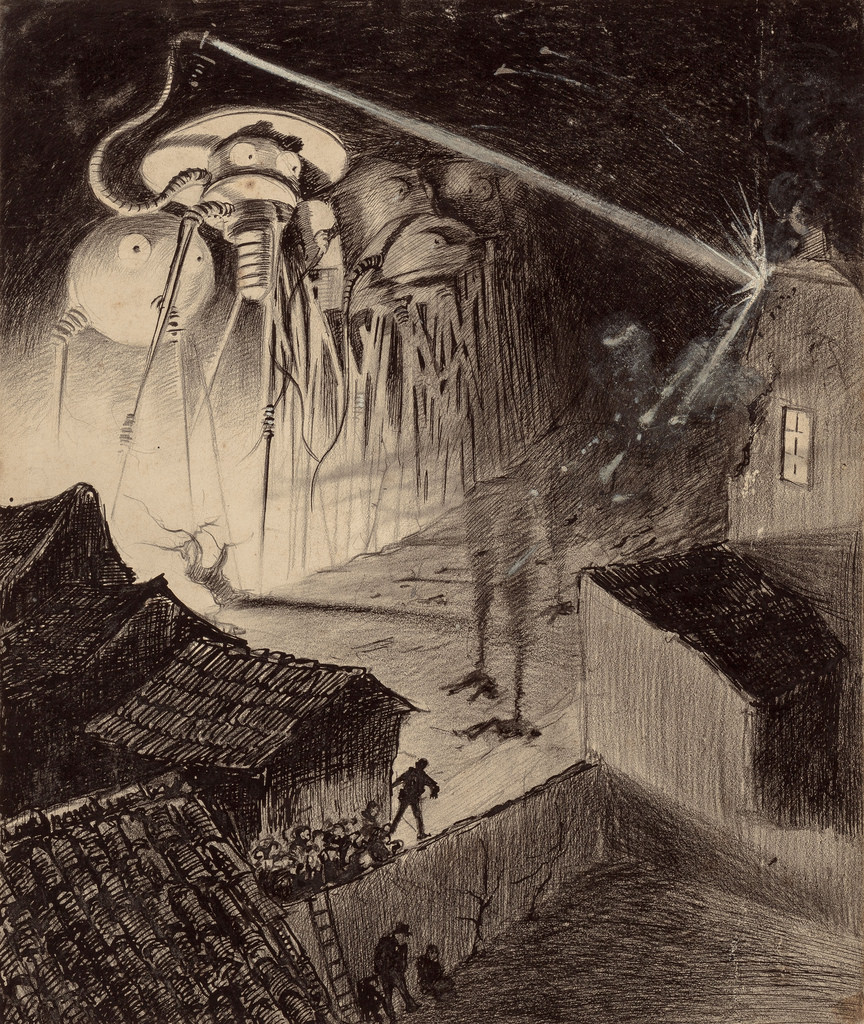

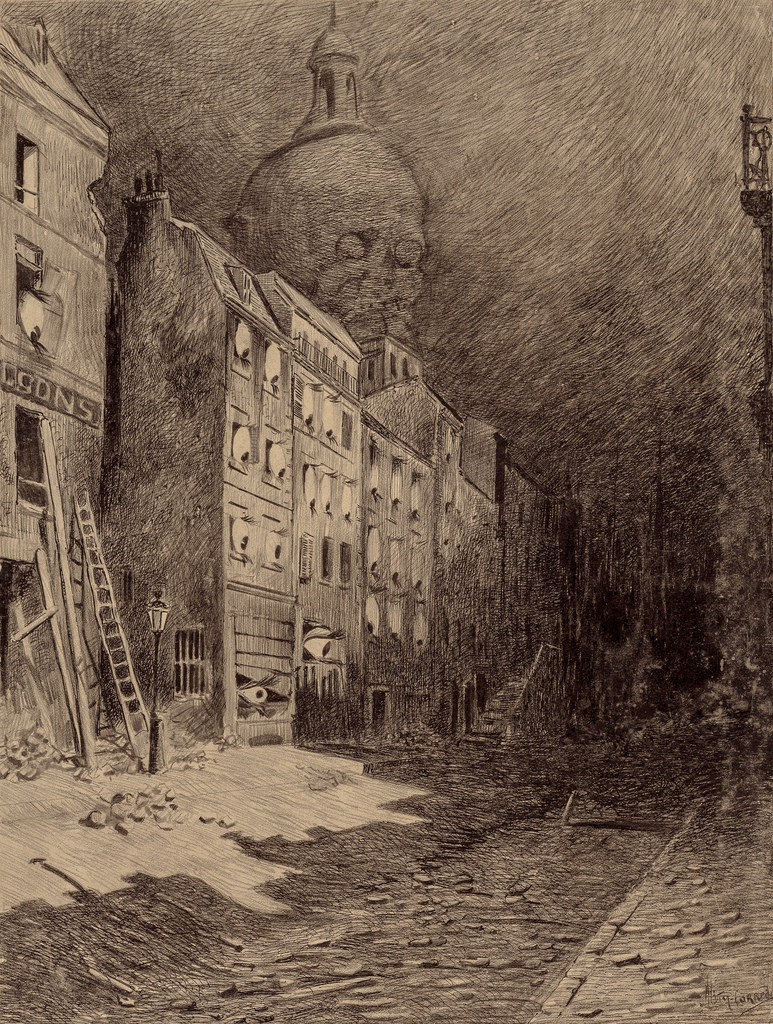

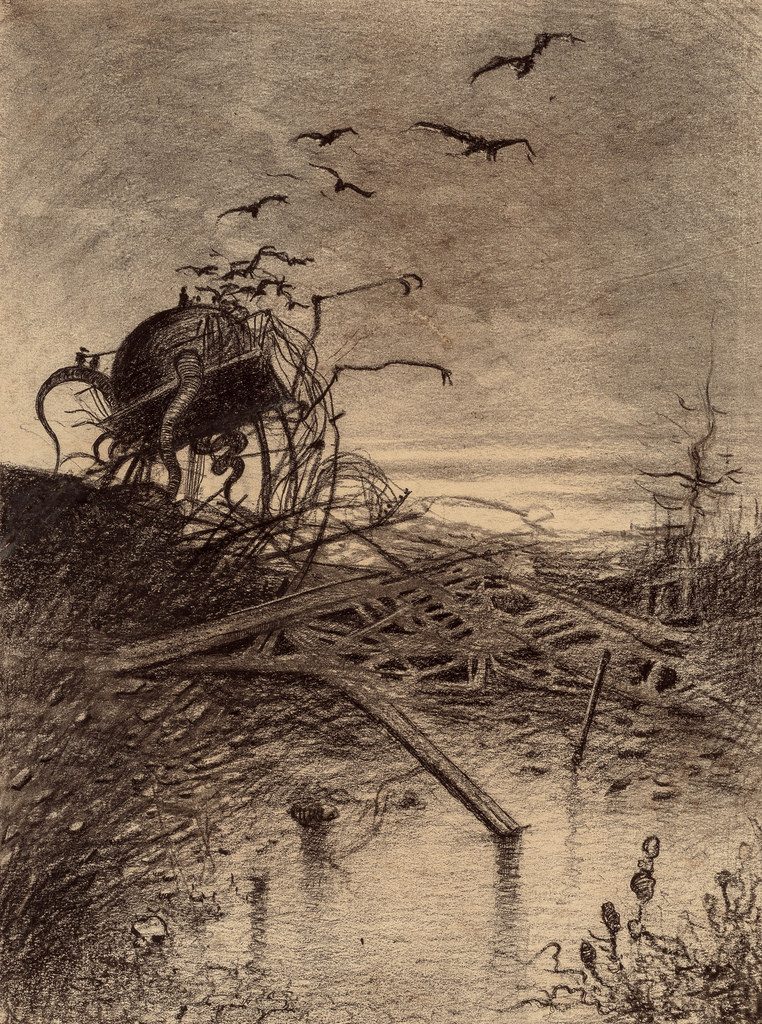

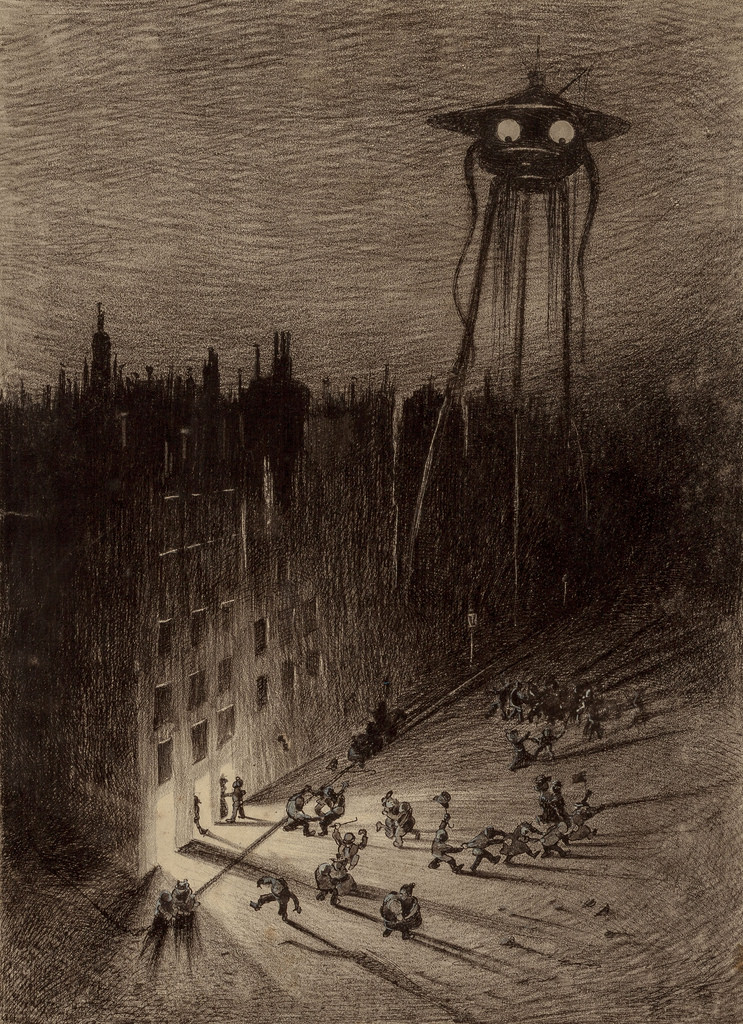

Indeed they capture the novel’s uncanny dread. Martian tripods loom, ghastly and cartoonish, above blasted realist landscapes and scenes of panic. In one illustration, a grotesque, tentacled Martian ravishes a nude woman. In a surrealist drawing of an abandoned London above, eyes protrude from the buildings, and a skeletal head appears above them. The alien technology often appears clumsy and unsophisticated, which contributes to the generally terrifying absurdity that emanates from these finely rendered plates.

Alvim Corrêa was a Brazilian artist living in Brussels and struggling for recognition in the European art world. His break seemed to come when the War of the Worlds illustrations were printed in a large-format, limited French edition of the book, with each of the 500 copies signed by the artist himself. Unfortunately, Corrêa’s tuberculosis killed him four years later. His War of the Worlds drawings did not bring him fame in his lifetime or after, but his work has been cherished since by a devoted cult following. The original prints you see here remained with the artist’s family until a sale of 31 of them in 1990. You can see many more, as well as scans from the book and a poster announcing the publication, at The Public Domain Review and the Monster Brains site.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015. Related Content: The Very First Illustrations of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1897) Edward Gorey Illustrates H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds in His Inimitable Gothic Style (1960) Orson Welles Meets H.G. Wells in 1940: The Legends Discuss War of the Worlds, Citizen Kane, and WWII H.G. Wells Interviews Joseph Stalin in 1934; Declares “I Am More to The Left Than You, Mr. Stalin” Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness |

| << Previous Day |

2025/02/11 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |